Iron Age Romford: Life Alongside the River During the Mid-First Millennium Bc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HA16 Rivers and Streams London's Rivers and Streams Resource

HA16 Rivers and Streams Definition All free-flowing watercourses above the tidal limit London’s rivers and streams resource The total length of watercourses (not including those with a tidal influence) are provided in table 1a and 1b. These figures are based on catchment areas and do not include all watercourses or small watercourses such as drainage ditches. Table 1a: Catchment area and length of fresh water rivers and streams in SE London Watercourse name Length (km) Catchment area (km2) Hogsmill 9.9 73 Surbiton stream 6.0 Bonesgate stream 5.0 Horton stream 5.3 Greens lane stream 1.8 Ewel court stream 2.7 Hogsmill stream 0.5 Beverley Brook 14.3 64 Kingsmere stream 3.1 Penponds overflow 1.3 Queensmere stream 2.4 Keswick avenue ditch 1.2 Cannizaro park stream 1.7 Coombe Brook 1 Pyl Brook 5.3 East Pyl Brook 3.9 old pyl ditch 0.7 Merton ditch culvert 4.3 Grand drive ditch 0.5 Wandle 26.7 202 Wimbledon park stream 1.6 Railway ditch 1.1 Summerstown ditch 2.2 Graveney/ Norbury brook 9.5 Figgs marsh ditch 3.6 Bunces ditch 1.2 Pickle ditch 0.9 Morden Hall loop 2.5 Beddington corner branch 0.7 Beddington effluent ditch 1.6 Oily ditch 3.9 Cemetery ditch 2.8 Therapia ditch 0.9 Micham road new culvert 2.1 Station farm ditch 0.7 Ravenbourne 17.4 180 Quaggy (kyd Brook) 5.6 Quaggy hither green 1 Grove park ditch 0.5 Milk street ditch 0.3 Ravensbourne honor oak 1.9 Pool river 5.1 Chaffinch Brook 4.4 Spring Brook 1.6 The Beck 7.8 St James stream 2.8 Nursery stream 3.3 Konstamm ditch 0.4 River Cray 12.6 45 River Shuttle 6.4 Wincham Stream 5.6 Marsh Dykes -

90 Shepherd Lancashire Miner in Walthamstow

A LANCAshiRE MinER in WALTHAMSTOW SAM WOOds And THE BY-ELECTION OF 1897 The Walthamstow by-election of 3 February 1897 was the most remarkable result of over seventy parliamentary contests during the 1895–1900 parliament. Sam Woods, a white-haired miner in his early fifties, unexpectedly became the first Liberal- Labour Member for Walthamstow. The Liberal press hailed the result as ‘the most astonishing political transformation of recent times’.1 However, The Times declared: ‘We had no notion that the crude, violent and round midnight on 3 Feb- Previous general election results: subversive Radicalism ruary 1897 the result of the 1892 of Mr Woods would Aparliamentary election for E. W. Byrne (Con) 6,115 the Walthamstow (South Western W. B. Whittingham (Lib) 4,965 find acceptance even Division of Essex) constituency was Con majority 1,150 announced at the old town hall in 1895 in a working-class Orford Road. The dramatic elec- E. W. Byrne (Con) 6,876 2 tion result was: A. H. Pollen (Lib) 4,523 constituency’. John Con majority 2,353 Shepherd tells the Sam Woods (Liberal-Labour) 6,518 Thomas Dewar (Cons.) 6,239 From 1886 to 1895 Waltham- story. Lib-Lab majority 279 stow returned Tory MPs, and the 24 Journal of Liberal History 90 Spring 2016 A LANCAshiRE MinER in WALTHAMSTOW SAM WOOds And THE BY-ELECTION OF 1897 Liberal Party saw the constituency Walthamstow contained the two trade, with many skilled workers, as a hopeless cause. The first work- largest electorates in the country. engaged mainly in house construc- man to contest Walthamstow, Sam The South-Western Division with tion. -

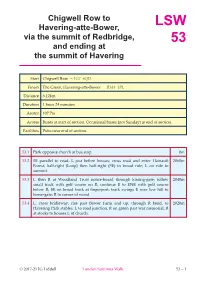

Chigwell Row to Havering-Atte-Bower, LSW Via the Summit of Redbridge, 53 and Ending at the Summit of Havering

Chigwell Row to Havering-atte-Bower, LSW via the summit of Redbridge, 53 and ending at the summit of Havering Start Chigwell Row — IG7 4QD Finish The Green, Havering-att e-Bower — RM4 1PL Distance 6.12km Duration 1 hour 24 minutes Ascent 107.7m Access Buses at start of section. Occasional buses (not Sunday) at end of section. Facilities Pubs near end of section. 53.1 Park opposite church at bus stop. 0m 53.2 SE parallel to road; L just before houses; cross road and enter Hainault 2060m Forest; half-right (Loop) then half-right (SE) to broad ride; L on ride to summit. 53.3 L then R at Woodland Trust notice-board through kissing-gate; follow 2040m small track with golf course on R; continue E to ENE with golf course below R; SE on broad track at fi ngerpost; track swings E over low hill to horse-gate; R to corner of wood. 53.4 L; cross bridleway; rise past Bower Farm and up, through R bend, to 2020m Havering Park stables; L to road junction, R on green past war memorial; R at stocks to houses L of church. © 2017-21 IG Liddell London Summits Walk 53 – 1 This section begins in the sett lement called Chigwell 53.1 Row, on the east side of the park. The “King’s Well” which gave Chigwell its name was situated in the Chigwell Row area. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the population of the small village grew: you will have passed the nonconformist chapel of that era as you entered the park coming from Grange Hill. -

Stakeholder Reference: Document Reference

Stakeholder Reference: Document Reference: Part A Making representation as Resident or Member of the General Public Personal Details Agent’s Details (if applicable) Title Mrs First Name michelle Last Name hilton Job Title (where relevant) Organisation (where relevant) Address …Redacted… Post Code Telephone Number …Redacted… E-mail Address …Redacted… Part B REPRESENTATION To which part of the Pre Submission Epping Forest District Local Plan does this representation relate? Paragraph: Policy: SP 6 Green Belt and District Open Land Policies Map: Yes Site Reference: STAP.R1 Settlement: Stapleford Abbots Do you consider this part of the Pre Submission Local Plan to be: Legally compliant: No Sound: No If no, then which of the soundness test(s) does it fail? Positively prepared,Effective,Justified,Consistent with national policy Complies with the duty to co-operate? No Please give details either of why you consider the Submission Version of the Local Plan is not legally compliant, is unsound or fails to comply with the duty to co-operate; or of why the Submission Version of the Local Plan is legally compliant, is sound or complies with the duty to co-operate. Please be as precise as possible. Please use this box to set out your comments. I consider the plan is not legal due to the following reasons. Firstly the nature it was applied for, no previous correspondence was sent to the local residence prior to the site being added to the local plan. The site was only added 4 days prior to the current plan being issued and then the site reference was changed!! also the address has been published wrongly. -

Buses from Manor Park

Buses from Manor Park N86 continues to Harold Hill Gallows Corner Leytonstone Walthamstow Leyton Whipps Cross Whipps Cross Green Man Romford Central Bakers Arms Roundabout Hospital Leytonstone Roundabout Wanstead Romford 86 101 WANSTEAD Market Chadwell Heath High Road Blake Hall Road Blake Hall Crescent Goodmayes South Grove LEYTONSTONE Tesco St. James Street Aldersbrook Road ROMFORD Queenswood Gardens Seven Kings WALTHAMSTOW Aldersbrook Road Ilford High Road Walthamstow New Road W19 Park Road Argall Avenue Industrial Area Ilford High Road Aldersbrook Road Aldborough Road South During late evenings, Route W19 Dover Road terminates at St. James Street Aldersbrook Road Ilford County Court (South Grove), and does not serve Empress Avenue Ilford High Road Argall Avenue Industrial Area. St. Peter and St. Paul Church Aldersbrook Road Merlin Road Aldersbrook Road Wanstead Park Avenue ILFORD 25 425 W19 N25 Forest Drive Ilford City of London Cemetery Hainault Street 104 Forest Drive Ilford Manor Park Capel Road Redbridge Central Library Gladding Road Chapel Road/Winston Way Clements Lane Ilford D ITTA ROA WH Romford Road 425 Manor Park [ North Circular Road Clapton Romford Road Kenninghall Road Little Ilford Lane Z CARLYLE ROAD S Romford Road T The yellow tinted area includes every A Seventh Avenue T I Clapton Pond bus stop up to about one-and-a-half O N Romford Road MANOR PA miles from Manor Park. Main stops are D A Rabbits Road O c R M R shown in the white area outside. RHA O DU A Romford Road D First Avenue Homerton Hospital ALBANY ROAD CARLTON -

Draft Recommendations on the New Electoral Arrangements for Havering Council

Draft recommendations on the new electoral arrangements for Havering Council Electoral review July 2020 Translations and other formats: To get this report in another language or in a large-print or Braille version, please contact the Local Government Boundary Commission for England at: Tel: 0330 500 1525 Email: [email protected] Licensing: The mapping in this report is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Keeper of Public Records © Crown copyright and database right. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and database right. Licence Number: GD 100049926 2020 A note on our mapping: The maps shown in this report are for illustrative purposes only. Whilst best efforts have been made by our staff to ensure that the maps included in this report are representative of the boundaries described by the text, there may be slight variations between these maps and the large PDF map that accompanies this report, or the digital mapping supplied on our consultation portal. This is due to the way in which the final mapped products are produced. The reader should therefore refer to either the large PDF supplied with this report or the digital mapping for the true likeness of the boundaries intended. The boundaries as shown on either the large PDF map or the digital mapping should always appear identical. Contents Introduction 1 Who we are and what we do 1 What is an electoral review? 1 Why Havering? 2 Our proposals for Havering 2 How will the recommendations affect you? 2 Have your -

Harold Wood Park Mangement Plan

CONTENTS Introduction 1 1. Site Overview 1.1 Havering 2 1.2 Strategic Framework 3 1.3 Site Description 3 1.4 History 4 1.5 Location and Transport Links 5 2. A Welcoming Place 2.1 Entrance Points 8 2.2 Entrance Signs 9 2.3 Accessibility 11 3. Heathy, Safe and Secure 3.1 Health and Safety Systems 12 3.2 Parks Protection Service 13 3.3 Parks Locking 16 3.4 Infrastructure 16 3.5 Parks Monitoring 17 4. Maintenance of Equipment, Buildings and Landscape 4.1 Horticultural Maintenance 19 4.2 Arboriculture Maintenance 22 4.3 Vehicles and Plant Maintenance 23 4.4 Parks Furniture 23 4.5 Play and Recreation 24 4.6 Parks Buildings 29 5. Litter, Cleanliness and Vandalism 5.1 Litter Management 31 5.2 Sweeping 31 5.3 Graffiti 31 5.4 Flytipping 32 5.5 Reporting 32 5.6 Dog Fouling 32 6. Environmental Manangement 6.1 Environmental Impact 34 6.2 Peat Use 35 6.3 Waste Minimisation 35 6.4 Pesticide Use 37 7. Biodiversity and Heritage 7.1 Management of natural features, wild fauna and flora 39 7.2 Conservation of landscape features 41 7.3 Conservation of buildings and structures 42 7.4 Havering Local Plan 43 7.5 Natural Ambition Booklet 43 7.6 Biodiversity Action Plan 45 8. Community Involvement 8.1 Council Surveys 46 8.2 User Groups 47 9. Marketing and Promotions 9.1 Parks Brochure 56 9.2 Social Media 56 9.3 Website 56 9.4 Interpretation Boards 56 9.5 Events 57 10. -

London 3 Essex V2.Xlsx

Round 1 26-Sep-20 Round 2 03-Oct-20 Round 3 10-Oct-20 Round 4 17-Oct-20 Round 5 24-Oct-20 Dagenham v Epping U. Clapton Harlow v Epping U. Clapton Dagenham v Harlow Romford & GP v Epping U. Clapton Dagenham v Campion East London v Harlow Romford & GP v Dagenham Epping U. Clapton v Campion Campion v Harlow Harlow v Romford & GP conf 'A' Romford & GP v Campion Campion v East London East London v Romford & GP East London v Dagenham Epping U. Clapton v East London 1 Braintree v Old Cooperians Braintree v Upminster Upminster v Old Cooperians Braintree v Mavericks Canvey Island v Old Cooperians conf 'B' Upminster v Kings Cross Steelers Old Cooperians v Mavericks Canvey Island v Braintree Upminster v Canvey Island Mavericks v Upminster 1 Canvey Island v Mavericks Kings Cross Steelers v Canvey Island Mavericks v Kings Cross Steelers Old Cooperians v Kings Cross Steelers Kings Cross Steelers v Braintree Round 6 31-Oct-20 Round 7 14-Nov-20 Round 8 21-Nov-20 Round 9 28-Nov-20 Round 10 05-Dec-20 East London vCampion Romford & GP vEast London Dagenham v East London Campion v Dagenham Epping U. Clapton v Dagenham Epping U. Clapton vHarlow Campion vEpping U. Clapton Harlow vCampion East London vEpping U. Clapton Harlow vEast London Dagenham v Romford & GP Harlow v Dagenham Epping U. Clapton v Romford & GP Romford & GP v Harlow Campion v Romford & GP Canvey Island v Kings Cross Steelers Kings Cross Steelers v Mavericks Kings Cross Steelers v Old Cooperians Old Cooperians v Canvey Island Old Cooperians v Braintree Upminster vBraintree Braintree vCanvey Island Canvey Island vUpminster Braintree vKings Cross Steelers Kings Cross Steelers vUpminster Mavericks v Old Cooperians Old Cooperians v Upminster Mavericks v Braintree Upminster v Mavericks Mavericks v Canvey Island Round 11 week 11 Round 12 week 12 Round 13 week 13 Round 14 week 14 Round 15 week 15 Braintree v Epping U. -

Buses from Ilford West and Liitle Ilford

Buses from Ilford West and Little Ilford N86 Harold Hill Harold Hill Gallows Dagnam Park Hilldene Corner 86 WALTHAMSTOW Square Avenue Romford South Grove for St. James Street Walthamstow Central ROMFORD Romford Market South Access Road Leyton Bakers Arms Romford Stadium W19 Walthamstow Whipps Cross Roundabout Argall Avenue Industrial Estate Whipps Cross Hospital Chadwell Heath ILFORD High Road Leytonstone Ilford 25 In late evenings, route W19 terminates Chapel Road/ 147 Goodmayes at St. James Street (South Grove), and does Leytonstone LEYTONSTONE Clements Lane High Road not serve Argall Avenue Industrial Estate. Green Man Roundabout 425 Ilford Seven Kings Ilford Hill N25 Ilford Aldersbrook Road W19 County Court SEVEN Queenswood Gardens Ilford High Road New Road Aldersbrook Road Ilford Ilford Ilford Ilford KINGS Park Road Redbridge High High High Road i Aldersbrook Road City of London Central Road Road Aldborough ALDERSBROOK Cemetery A Library Hainault St. Peter Road South Dover Road 4 D 0 A 6 Street & St. Paul RO Aldersbrook Road g D OR Church Empress Avenue MF RO Z G R Aldersbrook Road R A AB N BITS Merlin Road f T R H O [ A MANOR A M Aldersbrook Road DE D D SH Wanstead Park Avenue A SEVE RSINGHA RO R E O PARK L e D RI A Forest Road R I O NTH T l D F N M a T G City of London Cemetery RO L Manor Park E d \ H M AVE JAC AM K N Forest Drive I CO Romford Road/ L S RNW O IXTH A F AVENU ELL R Capel Road O High Street North FOURTH AVENUE N ST R T A E R ET UE H VE ] D THIRD AVENUE S Manor Park C E L N C VENUE I HARCO A E F UE R OND AVEN MEAN N WEST END I C RST AVENUE Woodgrange Park E U L A U N25 Romford Road LE R RT AV m Y R Shrewsbury Road ROAD R Oxford Circus O U URCH CH Little A OAD E ` Romford Road D E . -

Unit 26 Bates Industrial Estate, Harold Wood, Romford, RM3 0JA

Commercial - Essex 01245 261226 Unit 26 Bates Industrial Estate, Harold Wood, Romford, RM3 0JA To Let Industrial/Warehouse with Offices and Parking 409 Sq. M. (4,400 Sq. Ft.) • Available Immediately • Modern Building • Column Free Accommodation • Three Phase Power • Quoting Rent - £57,200 per annum Most active agency in Suffolk and North Essex Estates Gazette (February 2014) Details Location VAT Bates Industrial Estate is conveniently located South of We understand VAT is payable on the rent. the A12 approximately two miles from Junction 28 of the M25 motorway, providing easy access to the Legal Costs national motorway network. Harold Wood mainline station also provides a frequent services to London Each party to bear their own legal costs incurred in this Liverpool Street. transaction. Description Energy Rating The property comprises a modern mid terrace unit with Awaiting confirmation. ground and first floor office accommodation. WC and kitchenette facilities are provided. Particulars We understand the property benefits from allocated car Prepared November 2016. parking. Further details are available upon request. Viewing Business Rates Strictly by prior appointment with: Rateable Value £37,250 Fenn Wright Rates Payable (2016/2017) £18,250 approx. 20 Duke Street, Chelmsford, CM1 1HL 01245 261 226 Terms fennwright.co.uk The property is available on a new lease on terms to be Contact James Wright agreed. [email protected] Rent £57,200 per annum. Parculars for Unit 26 Bates Industrial Estate, Harold Wood, Romford, RM 3 0JA For further information 01245 261226 fennwright.co.uk Fenn Wright for themselves and for the vendors or lessors of this property whose agents they are give notice that: i. -

Essex. · [Kelly'~

360 COP ESSEX. · [KELLY'~ Coffin James. 3 Ba-rry terrace, Hainault Collins John Henry, I Stanhope villas, Cook J. W.Wentworthho.SnaresbrookeI road, Leytonstone e. Birkbeck road, Leytonstone " Cook Jas. 7 Argyle ter.Water la.Stratfrde Coker John S. The Place, Borley,Sndbry Collins Joseph Pnllen, Chestnut Tree Cook James William, Knowle ho. Brook Colbert Rt. 59 Claremont rd.Frst. gte e house, High road, Leytonstone • st. South Weald, Brentwood, Essex Coldercott Joseph, Woodvillevilla,Cleve- CoIlins Miss, 60 Wellesley I'd. Wanstead e Cook John, Witham land road, Snaresbrook CoIlins Mrs. 32 Maryland pt. Stratford e Cook John, 2 Barclay road, Leyton Cole Capt. Martin Geo.Rose val. Brentwd Collins Mrs. Wanstead lodge,Wanstead e Cook John, 3 Norfolk villas, Grange Park Cole Absalom, Little Waltham,Chlmsfrd Collins Wm. Brook Ho. farm, Chigwell road, Leyton Cole Alexander, Richmond house, Rom- Collins William Davis, Chestnut Tree Cook John, 138 Romford rd. Stratfot"d e ford road, Stratford e- house, High road, Leytonstone e Cook In. Will M.D. High st. Manningtree Cole Alfred, Laurel cottage, Gray road, Collison Albert, Great Bromley lodge, Cook Josepb, Lynton cottage, Fitzgerald Colchester Great Bromley, Colchester road, Wanstead Cole Arthnr, Osmond house, Church Collison Henry, Great Bromley lodge, Cook Joseph, 42 Tower Hamlets road, road, Leyton Great Bromley, Colchester Forest gate e Cole George, Billericay, Brentwood Collison Mrs. Great Bromley lodge, Cook Laurence, Roxburgh, Prospect. Cole George, 2 Eastgate street, Harwich Great Bromley, Colchester hill, Walthamstow Cole J.J.Abbey ter.Barking rd.Plaistow e Colliss David, 5 Westborne terrace, Cook Mrs. Eagl~ cot. Woodford green Plaistowe Grange Park road, Leyton Cook Mrs. -

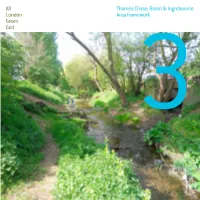

Thames Chase, Beam & Ingrebourne Area Framework

All Thames Chase, Beam & Ingrebourne London Area framework Green Grid 3 Contents 1 Foreword and Introduction 2 All London Green Grid Vision and Methodology 3 ALGG Framework Plan 4 ALGG Area Frameworks 5 ALGG Governance 6 Area Strategy 8 Area Description 9 Strategic Context 12 Vision 14 Objectives 18 Opportunities 20 Project Identification 22 Project update 24 Clusters 26 Projects Map 28 Rolling Projects List 32 Phase Two Delivery 34 Project Details 50 Forward Strategy 52 Gap Analysis 53 Recommendations 55 Appendices 56 Baseline Description 58 ALGG SPG Chapter 5 GG03 Links 60 Group Membership Note: This area framework should be read in tandem with All London Green Grid SPG Chapter 5 for GGA03 which contains statements in respect of Area Description, Strategic Corridors, Links and Opportunities. The ALGG SPG document is guidance that is supplementary to London Plan policies. While it does not have the same formal development plan status as these policies, it has been formally adopted by the Mayor as supplementary guidance under his powers under the Greater London Authority Act 1999 (as amended). Adoption followed a period of public consultation, and a summary of the comments received and the responses of the Mayor to those comments is available on the Greater London Authority website. It will therefore be a material consideration in drawing up development plan documents and in taking planning decisions. The All London Green Grid SPG was developed in parallel with the area frameworks it can be found at the following link: http://www.london.gov.uk/publication/all-london- green-grid-spg . Cover Image: The river Rom near Collier Row As a key partner, the Thames Chase Trust welcomes the opportunity to continue working with the All Foreword London Green Grid through the Area 3 Framework.