Colline Metallifere

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impacts in Real Estate of Landscape Values: Evidence from Tuscany (Italy)

sustainability Article The Impacts in Real Estate of Landscape Values: Evidence from Tuscany (Italy) Francesco Riccioli 1,* , Roberto Fratini 2 and Fabio Boncinelli 2 1 Department of Veterinary Science—Rural Economics Section, University of Pisa, 56124 Pisa, Italy 2 Department of Agriculture, Food, Environment and Forestry, University of Florence, 50144 Firenze, Italy; roberto.fratini@unifi.it (R.F.); fabio.boncinelli@unifi.it (F.B.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Using spatial econometric techniques and local spatial statistics, this study explores the relationships between the real estate values in Tuscany with the individual perception of satisfaction by landscape types. The analysis includes the usual territorial variables such as proximity to urban centres and roads. The landscape values are measured through a sample of respondents who expressed their aesthetic-visual perceptions of different types of land use. Results from a multivariate local Geary highlight that house prices are not spatial independent and that between the variables included in the analysis there is mainly a positive correlation. Specifically, the findings demonstrate a significant spatial dependence in real estate prices. The aesthetic values influence the real estate price throughout more a spatial indirect effect rather than the direct effect. Practically, house prices in specific areas are more influenced by aspects such as proximity to essential services. The results seem to show to live close to highly aesthetic environments not in these environments. The results relating to the distance from the main roads, however, seem counterintuitive. This result probably depends on the evidence that these areas suffer from greater traffic jam or pollution or they are preferred for alternative uses such as for locating industrial plants or big shopping centres rather than residential Citation: Riccioli, F.; Fratini, R.; use. -

Biological Monitoring System Continues in Scarlino

Biological monitoring system continues in Scarlino Fig ure 1- The returning canal at the sea of Scarlino The recorded death of fish in the river that flows out of the industrial zone of Scarlino has created the need of the installation of a biological alarm system. The decision was made to work with an automatic system, iTOXcontrol created by microLAN-The Netherlands represented in Italy by Ecotox Lds, which uses marine bacteria. The system compares the values of the light emission from these organisms at the entrance and exit of the canal, generating alarms in the presence of toxic substances. An innovative monitoring system has been installed in 2014 at the end of June, inside the river that flows out of the industrial zone of Scarlino (Province of Grosseto) in the zone of Casone. This area is the home of the most important industrial zone of the province, which includes production facilities of the following companies: Nuova Solmine, Tioxide Euro pe and Scarlino Energia. The plant uses only seawater for cooling, and this is pumped from an artificial river above the ground named delivery canal. After the industrial use, the water flows back into the sea using above ground canals, which are known as the returning canals. Within the main stream, different drains from the numerous purification plants unite as well as the communal ones of Scarlino and Follonica. The canal, provided by Nuova Solmine is from the ’60 and is located at the border between the two municipality of Scarlino and Follonica (GR). The study of the most adaptable monitoring system. -

Turismo-Spotivo.Pdf

Incanto Toscano Turismo Sportivo Incanto Toscano intende concentrare la sua attività in zone particolarmente importanti delle Province di Grosseto, Livorno, Pisa, Firenze, Siena, aree di forte rilevanza sia dal punto di vista naturalistico che di quello culturale, storico, tecnologico/scientifico, per offrire proposte di livello. Di seguito alcune delle nostre proposte per la realizzazione di escursioni, raggruppate in zone dalle caratteristiche omogenee e descritte in dettaglio. 1) AREA DELLE COLLINE METALLIFERE GROSSETANE: Parco delle Rocce e Museo della miniera, Tuscan Mining Geopark, Parco UNESCO, Gavorrano (GR) Parco Naturalistico delle Biancane, Monterotondo M.mo (GR) Riserva Naturale del Farma, i Canaloni, Torniella (GR) Punta Ala (GR). Storia, architettura, ambiente. Cala Violina, Riserva delle Bandite di Scarlino e il MAPS, Puntone di Follonica (GR) 2) AREA DELLA COSTA ETRUSCA, PARCHI DELLA VAL DI CORNIA, PROVINCIA DI LIVORNO E GROSSETO: La Buca delle Fate, Populonia (LI) Parco di Punta Falcone, Piombino (LI) Parco della Sterpaia, Piombino (LI) 3) PARCO REGIONALE DELLA MAREMMA: Principina a Mare (GR) Sentieri del Parco Regionale della Maremma, Monti dell'Uccellina , Alberese (GR) 4) ZONE UMIDE PROTETTE DELLA PROVINCIA DI GROSSETO: Diaccia Botrona e Museo della Casa Rossa Ximenes, Castiglione della Pescaia (GR) Riserva naturale Forestale della Feniglia e Laguna di Orbetello (GR) 5) ISOLE DEL PARCO NAZONALE DELL'ARCIPELAGO TOSCANO: Capraia Isola (LI) , “Dentro al vulcano” Isola di Pianosa, Comune di Campo nell'Elba (LI) Isola di Gorgona,, l'ultima Isola Carcere d'Europa (LI) Isola d'Elba, il regno dei minerali Isola del Giglio, e Isola di Giannutri (GR) 6) GIARDINI STORICI DI FIRENZE Giardino di Boboli, Firenze Giardino delle Rose e Giardino Bardini, Firenze Giardini di Villa La Petraia e Castello, Sesto F.no Giardino di Villa Demidoff a Pratolino, Il Gigante Appennino. -

Pubblicita' Ed Affissioni

COMUNE DI CAPALBIO (Provincia di Grosseto) Via G.Puccini,32 58011 Capalbio (GR) Tel . 0564897701 Fax 0564 897744 www.comune.capalbio.gr.it e-mail [email protected] STORIA DI CAPALBIO I Non si puo’ parlare della storia di Capalbio senza accennare al castello piu’ antico di Tricosto (oggi detto Capalbiaccio) di cui sono le rovine sul colle sito a Nord Ovest a due km dall’incrocio sulla S.S.Aurelia con accesso a Capalbio Scalo. Dall’alto del poggio e’ possibile abbracciare con un solo sguardo la Valle d’Oro. Esso ha all’incirca la forma di un triangolo, la cui base è rappresentata dai terreni impaludati che formano il prolungamento del lago di Burano verso Ansedonia, mentre i lati – piu’ o meno irregolari – sono costituiti da una serie di dolci rilievi collinosi che trovano il loro vertice in direzione del Monte Alzato. La Valle e’ oggi, e doveva essere anche in antico la pianura piu’ fertile dell’immediato retroterra della collina di Ansedonia. Allorquando (nel 273 a. C.) i romani fondarono su quella collina la colonia latina di Cosa, la Valle d’Oro entro’ a far parte del territorio della nuova citta’ e dovette essere divisa in piccoli lotti (probabilmente di un ettaro e mezzo di media) fra i primi coloni. L’indagine archeologica – tutt’ora in corso – ha rilevato tracce di insediamento deferibili al sistema di piccole fattorie unifamiliari che caratterizzo’ la proprieta’ e l’economia agricola del territorio per alcune generazioni fino a una data ancora imprecisata – ma da collocare certamente fra il II e la prima meta’ del I sec. -

The Tin Deposit of Monte Valerio (Tuscany): New Factual Observations for a Genetic Discussion"

R.ENDICONTl Soctel4 ltalf4'11Q; dt Mt..~ralogf4 ~ PelroloQia, J1 (I), J"J: pp. SZS-5J9 I. VENEllANDI ~PIRIU·J P. ZUFF.uDt· THE TIN DEPOSIT OF MONTE VALERIO (TUSCANY): NEW FACTUAL OBSERVATIONS FOR A GENETIC DISCUSSION" ABSTIlACT. - All the Authors which were concerned with Monte Valerio supported pyrometasomadc or pneumatholitic-hydrolhermal genetic processes, linked to the Mio-Pliocene acidic magmatic activity. The present Authors, on the basis of factual observations directly achieved. and/or reported in the existing literature, suggest syn.sedimentary Tin deposition, followed by partial supergene remobilization, and assignc a very limited role (if any) to ~ Mio-PliOCttlC: magtnatism and metamOrphism on Tin distribution. RuSSUNTO. - Tuui g1i Autori cbe si sono lino ad ora occupati di Monte Valeric ne _tengooo una ,enes.i p~tka 0 pneumatolitiCo-idrotermale, conne5SII all'altivita mqmatica acida mio-pliocenia. Per parte nostra, sclla base di dati di osservaziooe rilevali sui tc:rreno 0 ricavati da1la lettaatum aUtmte, suggeriamo una genes.i per deposizione sin-sedi mentrit, squita da (llltZia1e rimobilizzazion supergenia, e riten.iamo cbe il rooJo del magmarismo mio-pliocenico su1la dinribuzione deIIo Sn neII'aCCll di Monte Valerio sit stato asui limitaW se non acIdirittura nullo. REsUME.. - Toos les Auteurs qui jusqu'ici se sont interesse. du gisement de Monte Valerio en soutiennent une genese pyrometasomadque ou pneumatholitique-hydrothennale, en rapport avec I'Rctivite magmatique acide mio-plioc-.:ne. De, notre part, sur la base des donn~s directement relevm sur le terrain ou tirees de la liuerature existente, nous suggerons une g~nese par d~pot sin-sedimentaire, suivie par une dmobilisation particlle supergenique; ncus croyons par consequent que le role du magmadsme mio-pliocene sur la distribution du Sn dans !'aire de Monte Valerio a ele tIft limite si non tout a f.il inexistant. -

Name: Sovana Rosso Farm: Cencini Area of Production: Marsiliana

Name: Sovana Rosso Farm: Cencini Area of production: Marsiliana-Guinzoni Manciano Year: 2009 Denomination: Red Doc Sovana Quantity produced: 10.000 0,750ml Bordoleses Grapes: Sangiovese, Cabernet-Sauvignon, in the proportions established by the disciplinary one Altitude / Exposure: 150mt Slms, Northwest Characteristics: Alcoholic gradation 13% Vol Composition Land: Clayey Geographical aspect Place Marsiliana-Guinzoni Manciano (Gr), hilly zone, altitude of 150mt Slms, that contributes to a rapid and complete maturation of the grapes, that they bring an intensity elevated polifenolica. Atmosfere typical of the Maremma Tuscany, warm dry land, mild, few summer rains, moderate breeze coming from the near Tyrrhenian Sea. The Vineyards Currently the vineyards occupy a business surface of 4,5 it has, exposed northwestern. The mineral composition of the clayey-warm ground, confers to the wine it structures solid and good fineness. The form of breeding is cord speronato with sixth of plant 3x1. The surrender and' 80 Qls /ha. The Vintage The harvest of the red grapes happens between the 20 of September and on October 20, after an accurate selection of the grapes, exclusively manual, you abandons in cassettes from 10Kg with which are transported to the wine cellar, so that to make sure the greatest integrity possible of the grapes. The vinification After the harvest grape arrives in the business wine cellar, the clusters come to remove the rasps and envoys to ferment in the tubs of cement from 40 Qts with manual fulling, constant temperature. The period of fermentation / maceration is of 18-21 days to a temperature checked among 25°-28°C. -

Climate Changes

The Interreg MED COMPOSE project Communities with positive energy Energy efficiency and renewable energy sources Tips to reduce our own ecological footprint by saving compose.interreg-med.eu The Capalbio and Giove Municipalities joined the Interreg MED COMPOSE project. www.comune.capalbio.gr.it www.comune.giove.tr.it We apologise for any typos or errors which may have accidentally been left in the Booklet text. THANK YOU! Summary Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 1 The Interreg MED COMPOSE Project ....................................................................................... 2 Activities and Expected Results ............................................................................................ 2 Environment, Energy, Climate and Climate system, Greenhouse effect and Climate changes ........................................................................................................................ 4 Environment and Energy ...................................................................................................... 4 Climate and Climate Changes ............................................................................................... 5 Climate Changes and Mankind ............................................................................................. 6 Climate Changes: what impacts? ......................................................................................... 7 Mitigation and adaptation -

Frutti Vitigni Ed Olivi Colline Metallifere

Frutti Vitigni ed Olivi delle Colline Metallifere Per una Moderna Utilizzazione di Antiche Piante Locali Frutti Vitigni ed Olivi delle Colline Metallifere Claudio Cantini, Tomaso Ceccarelli, Alessandra Betti, Graziano Sani Istituto per la Valorizzazione del Legno e delle Specie Arboree Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche Ringraziamenti Si ringrazia il Dott. Marco Pollini dell’Unione dei Comuni Montani Colline Metallifere e l’Associazione “Per Prata tra passato e futuro “ Premessa Questa pubblicazione riassume i lavori eseguiti nell’ambito di diversi progetti realizzati nel corso degli anni dall’Istituto per la Valorizzazione del Legno e delle Specie Arboree (IVALSA) del Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche sul territorio delle Colline Metallifere di pertinenza dei comuni di Massa Marittima, Montieri, Monterotondo e Roccastrada. I lavori hanno preso inizio nel 2003 con un finanziamento dell’"Istituto Nazionale per la Ricerca della Montagna" per conto del Comune di Massa Marittima. Il progetto dal titolo "Progetto pilota di sviluppo integrato per favorire la residenza stabile nel territorio montano del Comune di Massa Marittima" ha visto il coordinamento scientifico della Facoltà di Architettura di Ferrara ed il supporto di ricercatori e borsisti di diversi Enti Pubblici (CNR- IVALSA, CRA di Firenze, etc.). Prata, frazione di Massa Marittima, venne individuata come una zona di potenziale interesse per la sua tradizione agricola, prima ancora che mineraria (dalla Grancia dello Spedale di Santa Maria della Scala risalente alla fine del quattrocento in poi). Su questa spinta, l’allora Comunità Montana Colline Metallifere avviò, all’interno di un progetto comunitario Leader Plus, una azione sul recupero delle varietà agricole locali con un finanziamento GAL. -

La Viabilità in Provincia Di Grosseto Fra L’Età Romana E Il Medioevo

92 Guida agli edifici sacri della Maremma LA VIABILITÀ IN PROVINCIA DI GROSSETO FRA L’ETÀ ROMANA E IL MEDIOEVO Carlo Citter LA VIABILITÀ ROMANA L’area oggi delimitata dalla provincia di Grosseto fu attraversata da una fitta rete di strade costruite per lo più fra III e II secolo a.C., di cui le principali erano: l’Aurelia (Vetus e Nova e Aemilia Scauri) e, nel sovane- se, la Clodia. Le fonti documentarie per la ricostruzione della viabilità romana principale sono: la Cosmografia dell’Anonimo Ravennate, la Geografia di Guidone (che indicheremo da ora in poi rispettivamente AR e GG, edite in Schnetz a cura di, 1940); la Tabula Peutingeriana (da ora TP edita in Miller 1916) e l’Itinerarium Antonini Imperatoris (da ora IA in Cuntz 1929). Ai fini della ricostruzione della viabilità tardorepubblicana non pos- sono essere usate AR e GG che sono invece, rispettivamente, una fonte bizantina e del pieno Medioevo, che registrano le modifiche all’assetto tradizionale a seguito delle vicende belliche del VI secolo. La viabilità romana è stata oggetto di studi di diverso spessore scien- tifico, talora ai limiti della fantasia, più spesso del tutto privi di un ri- scontro topografico. È chiaro, infatti, che la sola ricostruzione ideale di tracciati, svincolata da ogni verifica sulla natura geografica dei territori che attraversavano, è comprensibile solo in assenza di un’archeologia del paesaggio. L’A URELIA Cominciamo con i tracciati dell’Aurelia. Ho già trattato altrove il pro- blema della sinossi delle proposte che la ricca letteratura sull’argomento offre e rimando senz’altro a quel contributo per tutti i dettagli. -

Print the Leaflet of the Museum System Monte Amiata

The Amiata Museum system was set up by the Comunità Montana Amiata Santa Caterina Ethnographic Museum CASA MUSEO DI MONTICELLO AMIATA - CINIGIANO Via Grande, Monticello Amiata, Cinigiano (Gr) of Grosseto to valorize the network of thematic and environmental facilities - Roccalbegna Ph. +39 328 4871086 +39 0564 993407 (Comune) +39 0564 969602 (Com. Montana) spread throughout its territory. The System is a territorial container whose Santa Caterina’s ethnographic collection is housed in the www.comune-cinigiano.com special museum identity is represented by the tight relationship between the rooms of an old blacksmith forge. The museum tells the www.sistemamusealeamiata.it environment and landscape values and the anthropological and historical- story of Monte Amiata’s toil, folk customs and rituals tied artistic elements of Monte Amiata. The Amiata Museum system is part of the to fire and trees. The exhibition has two sections: the first MUSEO DELLA VITE E DEL VINO DI MONTENERO D’ORCIA - CASTEL DEL PIANO Maremma Museums, the museum network of the Grosseto province and is a houses a collection of items used for work and household Piazza Centrale 2, Montenero d’Orcia - Castel del Piano (Gr) useful tool to valorize smaller isolated cultural areas which characterize the activities tied to the fire cycle. The second features the Phone +39 0564 994630 (Strada del Vino Montecucco e dei sapori d’Amiata) Tel. +39 0564 969602 (Comunità Montana) GROSSETO’S AMIATA MUSEUMS Amiata territory. “stollo” or haystack pole, long wooden pole which synthe- www.stradadelvinomontecucco.it sizes the Focarazza feast: ancient ritual to honor Santa Ca- www.sistemamusealeamiata.it For the demoethnoanthropological section terina d’Alessandria which is held each year on November we would like to mention: 24th, the most important local feast for the entire com- munity. -

Miniguida Colline Metallifere Massa Marittima

Miniguida Colline Metallifere Massa Marittima Il suo nome deriva dal termine massa, che in epoca romana indicava le proprietà fondiarie sotto un’unica amministrazione ed in età longobarda piccoli feudi. Nei secoli il termine massa è stato accompagnato da diverse specificazioni come “Veternensis”, “Vetuloniensis”, “Metallorum” fino all’attuale “Marittima”. Risalgono al periodo tra Il territorio l’ottavo ed il nono secolo dopo Cristo le prime attestazioni documentarie relative a Massa. È con il trasferimento a Massa della sede episcopale da Populonia che si ha però il decollo del piccolo borgo. Lo sviluppo delle attività produttive, fin dall’antichità conosciute nella zona, legate all’estrazione e alla lavorazione dei metalli portò inoltre grande floridezza economica. Ciò permise un notevole sviluppo urbanistico del centro abitato. Sottraendosi alle residue prerogative vescovili nel 1225 i massetani videro la nascita del Libero Comune (repubblica massetana). Questa data rappresenta un momento fondamentale nella sua storia. In questo periodo viene promulgato lo statuto politico- amministrativo e portato avanti il nuovo assetto urbanistico nel quale si integrano la ristrutturazione della Città Vecchia e la pianificazione di una nuova espansione urbana, la Città Nuova. La nascita del libero comune dà nuovo impulso alle attività produttive legate all’estrazione dei metalli. In questo periodo viene scritto il primo Codice Minerario d’Europa. Nel 1337 Massa cadde sotto la dominazione senese. Cattedrale di San Cerbone 1 Miniguida Colline Metallifere Luoghi da visitare Il Capoluogo La piazza Garibaldi è il cuore della Città Vecchia e riunisce i più importanti edifici pubblici del libero comune medievale. La Basilica Cattedrale di San Cerbone, costruita tra il XII ed il XIII sec., domina la piazza. -

Introduction

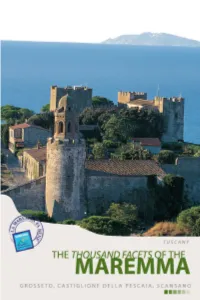

TUSCANY MAREMMA GROSSETO, CASTIGLIONE DELLA PESCAIA, SCANSANO GROSSETO, CASTIGLIONE DELLA PESCAIA, SCANSANO INTRODUCTION cansano, Grosseto, Castiglione della Pescaia: a fresco of hills, planted fields, towns and citadels, sea and beaches, becoming a glowing mosaic embellished by timeless architecture. Here you find one of the most beautiful, warm and Ssincere expressions of the spell cast by the magical Maremma. Qualities lost elsewhere have been carefully nurtured here. The inland is prosperous with naturally fertile farmland that yields high quality, genuine produce. The plain offers GROSSETO, CASTIGLIONE DELLA PESCAIA, SCANSANO THE THOUSAND FACETS OF THE MAREMMA wetlands, rare types of fauna and uncontaminated flora. The sea bathes a coast where flowered beaches, sandy dunes, pine groves and brackish marshes alternate and open into coves with charming tourist ports and modern, well-equipped beaches. What strikes you and may well tie you to this place long after your visit, is the life style you may enjoy the sea, a trip into the Etruscan past, better represented here than anywhere else, then a visit to the villages and towns where the atmosphere and art of the Middle Ages remains firmly embedded. GROSSETO, CASTIGLIONE DELLA PESCAIA, SCANSANO THE THOUSAND FACETS OF THE MAREMMA GROSSETO his beautiful and noble city is the vital centre of the Maremma. Grosseto lies in a green plain traced by the flow of the Ombrone and its origins go back to the powerful Etruscan and Roman city of Roselle. Walking among the military, civil Tand religious monuments, you are able to cover twelve centuries of history and envision each of the periods and rulers as they are unveiled, layer by layer, before you.