Housing, Land and Property and Access To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

安全理事会 Distr.: General 8 November 2012 Chinese Original: English

联合国 S/2012/540 安全理事会 Distr.: General 8 November 2012 Chinese Original: English 2012年7月11日阿拉伯叙利亚共和国常驻联合国代表给秘书长和安全 理事会主席的同文信 奉我国政府指示,并继我 2012 年 4 月 16 至 20 日和 23 日至 25 日、5 月 7 日、11 日、14 日至 16 日、18 日、21 日、24 日、29 日、31 日、6 月 1 日、4 日、 6 日、7 日、11 日、19 日、20 日、25 日、27 日和 28 日、7 月 2 日、3 日、9 日 和 11 日的信,谨随函附上 2012 年 7 月 7 日武装团伙在叙利亚境内违反停止暴力 规定行为的详细清单(见附件)。 请将本信及其附件作为安全理事会的文件分发为荷。 常驻代表 大使 巴沙尔·贾法里(签名) 12-58085 (C) 121112 201112 *1258085C* S/2012/540 2012年7月11日阿拉伯叙利亚共和国常驻联合国代表给秘书长和安全 理事会主席的同文信的附件 [原件:阿拉伯文] Saturday, 7 July 2012ggz Rif Dimashq governorate 1. At 2145 hours on 6 July 2012, an armed terrorist group stole the car of Colonel Abdulrahman Qalih of the law enforcement forces as he was passing on the Dayr Atiyah – Maksar road. 2. At 2200 hours on 6 July 2012, an armed terrorist group opened fire on law enforcement officers in Tallat al-Sultan, Masakin al-Tawafiq and the orchards of Qatana, wounding one officer. 3. At 0630 hours, an armed terrorist group opened fire on and wounded Warrant Officer Ahmad Ali. 4. At 0800 hours, an armed terrorist group planted an explosive device in the Sabburah area. As military engineers attempted to defuse it, the device exploded. One officer lost his right foot and another was burned. 5. At 0800 hours, an armed terrorist group opened fire on law enforcement officers in Ayn Tarma, wounding one officer. 6. At 0900 hours, an armed terrorist group opened fire on a law enforcement forces car on Yabrud bridge, Nabk town, killing Conscript Sawmar al-Musa Abd Jibawi and wounding two other officers. -

Policy Notes for the Trump Notes Administration the Washington Institute for Near East Policy ■ 2018 ■ Pn55

TRANSITION 2017 POLICYPOLICY NOTES FOR THE TRUMP NOTES ADMINISTRATION THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ 2018 ■ PN55 TUNISIAN FOREIGN FIGHTERS IN IRAQ AND SYRIA AARON Y. ZELIN Tunisia should really open its embassy in Raqqa, not Damascus. That’s where its people are. —ABU KHALED, AN ISLAMIC STATE SPY1 THE PAST FEW YEARS have seen rising interest in foreign fighting as a general phenomenon and in fighters joining jihadist groups in particular. Tunisians figure disproportionately among the foreign jihadist cohort, yet their ubiquity is somewhat confounding. Why Tunisians? This study aims to bring clarity to this question by examining Tunisia’s foreign fighter networks mobilized to Syria and Iraq since 2011, when insurgencies shook those two countries amid the broader Arab Spring uprisings. ©2018 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ NO. 30 ■ JANUARY 2017 AARON Y. ZELIN Along with seeking to determine what motivated Evolution of Tunisian Participation these individuals, it endeavors to reconcile estimated in the Iraq Jihad numbers of Tunisians who actually traveled, who were killed in theater, and who returned home. The find- Although the involvement of Tunisians in foreign jihad ings are based on a wide range of sources in multiple campaigns predates the 2003 Iraq war, that conflict languages as well as data sets created by the author inspired a new generation of recruits whose effects since 2011. Another way of framing the discussion will lasted into the aftermath of the Tunisian revolution. center on Tunisians who participated in the jihad fol- These individuals fought in groups such as Abu Musab lowing the 2003 U.S. -

BREAD and BAKERY DASHBOARD Northwest Syria Bread and Bakery Assistance 12 MARCH 2021

BREAD AND BAKERY DASHBOARD Northwest Syria Bread and Bakery Assistance 12 MARCH 2021 ISSUE #7 • PAGE 1 Reporting Period: DECEMBER 2020 Lower Shyookh Turkey Turkey Ain Al Arab Raju 92% 100% Jarablus Syrian Arab Sharan Republic Bulbul 100% Jarablus Lebanon Iraq 100% 100% Ghandorah Suran Jordan A'zaz 100% 53% 100% 55% Aghtrin Ar-Ra'ee Ma'btali 52% 100% Afrin A'zaz Mare' 100% of the Population Sheikh Menbij El-Hadid 37% 52% in NWS (including Tell 85% Tall Refaat A'rima Abiad district) don’t meet the Afrin 76% minimum daily need of bread Jandairis Abu Qalqal based on the 5Ws data. Nabul Al Bab Al Bab Ain al Arab Turkey Daret Azza Haritan Tadaf Tell Abiad 59% Harim 71% 100% Aleppo Rasm Haram 73% Qourqeena Dana AleppoEl-Imam Suluk Jebel Saman Kafr 50% Eastern Tell Abiad 100% Takharim Atareb 73% Kwaires Ain Al Ar-Raqqa Salqin 52% Dayr Hafir Menbij Maaret Arab Harim Tamsrin Sarin 100% Ar-Raqqa 71% 56% 25% Ein Issa Jebel Saman As-Safira Maskana 45% Armanaz Teftnaz Ar-Raqqa Zarbah Hadher Ar-Raqqa 73% Al-Khafsa Banan 0 7.5 15 30 Km Darkosh Bennsh Janudiyeh 57% 36% Idleb 100% % Bread Production vs Population # of Total Bread / Flour Sarmin As-Safira Minimum Needs of Bread Q4 2020* Beneficiaries Assisted Idleb including WFP Programmes 76% Jisr-Ash-Shugur Ariha Hajeb in December 2020 0 - 99 % Mhambal Saraqab 1 - 50,000 77% 61% Tall Ed-daman 50,001 - 100,000 Badama 72% Equal or More than 100% 100,001 - 200,000 Jisr-Ash-Shugur Idleb Ariha Abul Thohur Monthly Bread Production in MT More than 200,000 81% Khanaser Q4 2020 Ehsem Not reported to 4W’s 1 cm 3720 MT Subsidized Bread Al Ma'ra Data Source: FSL Cluster & iMMAP *The represented percentages in circles on the map refer to the availability of bread by calculating Unsubsidized Bread** Disclaimer: The Boundaries and names shown Ma'arrat 0.50 cm 1860 MT the gap between currently produced bread and bread needs of the population at sub-district level. -

Political Economy Report English F

P a g e | 1 P a g e | 2 P a g e | 3 THE POLITICAL ECONOMY And ITS SOCIAL RAMIFICATIONS IN THREE SYRIAN CITIES: TARTOUS, Qamishli and Azaz Economic developments and humanitarian aid throughout the years of the conflict, and their effect on the value chains of different products and their interrelation with economic, political and administrative factors. January 2021 P a g e | 4 KEY MESSAGES • The three studied cities are located in different areas of control: Tartous is under the existing Syrian authority, Azaz is within the “Euphrates Shield” areas controlled by Turkey and the armed “opposition” factions loyal to it, and most of Qamishli is under the authority of the “Syrian Democratic Forces” and the “Self-Administration” emanating from it. Each of these regions has its own characteristics in terms of the "political war economy". • After ten years of conflict, the political economy in Syria today differs significantly from its pre-conflict conditions due to specific mechanisms that resulted from the war, the actual division of the country, and unilateral measures (sanctions). • An economic and financial crisis had hit all regions of Syria in 2020, in line with the Lebanese crisis. This led to a significant collapse in the exchange rate of the Syrian pound and a significant increase in inflation. This crisis destabilized the networks of production and marketing of goods and services, within each area of control and between these areas, and then the crisis of the Covid-19 pandemic exacerbated this deterioration. • This crisis affected the living conditions of the population. The monthly minimum survival expenditure basket (SMEB) defined by aid agencies for an individual amounted to 45 working days of salaries for an unskilled worker in Azaz, 37 days in Tartous and 22 days in Qamishli. -

Rojavadevrimi+Full+75Dpi.Pdf

Kitaba ilişkin bilinmesi gerekenler Elinizdeki kitabın orijinali 2014 ve 2015 yıllarında Almanca dilinde üç yazar tarafından yazıldı ve Rosa Lüksemburg Vakfı’nın desteğiyle “VSA Verlag” adlı yayınevi tarafından Almanya’da yayınlandı. 2018 yılında Almanca dilinde 4. baskısı güncellenip basılarak önemli ilgi gören bu kitap, 2016 Ekim ayında “Pluto Press” adlı yayınevi tarafından İngilizce dilinde Birleşik Krallık ‘ta yayınlandı. Bu kitabın İngilizce çevirisi ABD’de yaşayan yazar ve aktivist Janet Biehl tarafından yapıldı ve sonrasında üç yazar tarafından 2016 ilkbaharında güncellendi. En başından beri kitabın Türkçe dilinde de basılıp yayınlanası için bir planlama yapıldı. Bu amaçla bir grup gönüllü İngilizce versiyonu temel alarak Türkçe çevirisini yaptı. Türkiye’deki siyasal gelişme ve zorluklardan dolayı gecikmeler ortaya çıkınca yazarlar kitabın basılmasını 2016 yılından daha ileri bir tarihe alma kararını aldı. Bu sırada tekrar Rojava’ya giden yazarlar, elde ettikleri bilgilerle Türkçe çeviriyi doğrudan Türkçe dilinde 2017 ve 2018 yıllarında güncelleyip genişletti. Bu gelişmelere redaksiyon çalışmaları da eklenince kitabın Türkçe dilinde yayınlanması 2018 yılında olması gerekirken 2019 yılına sarktı. 2016 yılından beri kitap ayrıca Farsça, Rusça, Yunanca, İtalyanca, İsveççe, Polonca, Slovence, İspanyolca dillerine çevrilip yayınlandı. Arapça ve Kürtçe çeviriler devam etmektedir. Kitap Ağustos 2019’da yayınlandı. Ancak kitapta en son Eylül 2018’de içeriksel güncellenmeler yapıldı. 2018 yazın durum ve atmosferine göre yazıldı. Kitapta kullanılan resimlerde eğer kaynak belirtilmemişse, resimler yazarlara aittir. Aksi durumda her resmin altında resimlerin sahibi belirtilmektedir. Kapaktaki resim Rojava’da kurulmuş kadın köyü Jinwar’ı göstermekte ve Özgür Rojava Kadın Vakfı’na (WJAR) aittir. Bu kitap herhangi bir yayınevi tarafından yayınlanmamaktadır. Herkes bu kitaba erişimde serbesttir. Kitabı elektronik ve basılı olarak istediğiniz gibi yayabilirsiniz, ancak bu kitaptan gelir ve para elde etmek yazarlar tarafından izin verilmemektedir. -

A Blood-Soaked Olive: What Is the Situation in Afrin Today? by Anthony Avice Du Buisson - 06/10/2018 01:23

www.theregion.org A blood-soaked olive: what is the situation in Afrin today? by Anthony Avice Du Buisson - 06/10/2018 01:23 Afrin Canton in Syria’s northwest was once a haven for thousands of people fleeing the country’s civil war. Consisting of beautiful fields of olive trees scattered across the region from Rajo to Jindires, locals harvested the land and made a living on its rich soil. This changed when the region came under Turkish occupation this year. Operation Olive Branch: Under the governance of the Afrin Council – a part of the ‘Democratic Federation of Northern Syria’ (DFNS) – the region was relatively stable. The council’s members consisted of locally elected officials from a variety of backgrounds, such as Kurdish official Aldar Xelil who formerly co-headed the Movement for a Democratic Society (TEVDEM) – a political coalition of parties governing Northern Syria. Children studied in their mother tongue— Kurdish, Arabic, or Syriac— in a country where the Ba’athists once banned Kurdish education. The local Self-Defence Forces (HXP) worked in conjunction with the People’s Protection Units (YPG) to keep the area secure from existential threats such as Turkish Security forces (TSK) and Free Syrian Army (FSA) attacks. This arrangement continued until early 2018, when Turkey unleashed a full-scale military operation called ‘ Operation Olive Branch’ to oust TEVDEM from Afrin. The Turkish government views TEVDEM and its leading party, the Democratic Union Party (PYD), as an extension of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) – listed as a terrorist organisation in Turkey. Under the pretext of defending its borders from terrorism, the Turkish government sent thousands of troops into Afrin with the assistance of forces from its allies in Idlib and its occupied Euphrates Shield territories. -

FIGHTING SPIRIT USS John S

MILITARY FACES COLLEGE BASKETBALL Pearl Harbor survivor ‘The Photograph’ Jalen Smith leading and USS Arizona crew evokes black romantic No. 9 Terrapins to member dies at 97 dramas of the ’90s the top of Big Ten Page 3 Page 11 Back page Taliban says peace deal with US to be signed by month’s end » Page 5 stripes.com Volume 78, No. 217 ©SS 2020 TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 18, 2020 50¢/Free to Deployed Areas Warship crash survivors say Navy struggled to treat them BY MEGAN ROSE, KENGO TSUTSUMI AND T. CHRISTIAN MILLER ProPublica Two and a half years after a massive oil tanker cleaved the side of the USS John S. McCain, leaving a gaping hole and kill- ing 10 sailors, hospital corpsman Mike Collins is still haunted by the aftermath. That morning in August 2017, awoken by the thunderous shak- ing, the 23-year-old was thrust into round-the- clock motion: ‘ Why I Tending to the wasn’t chemical burns of the sailors getting whose sleeping any help area flooded, their flesh raw was from the fuel drowning that spilled in me in with the sea- Marine Sgt. Melissa Paul water. Collect- stands at the obstacle stress. ing the heavy ’ course on Naval Weapons stack of the Mike Collins Station Yorktown in dead’s medical FIGHTING SPIRIT USS John S. Virginia on Jan. 31 . records. Stay- McCain crash ing up late try- Following a successful survivor ing to purge the wrestling career stink of diesel Marine uses wrestling past to train martial arts teachers — including being named that clung to their uniforms, so an Olympic alternate in 2012 — Paul now serves the clothes could be returned to BY BROCK VERGAKIS grieving families. -

Security Council Distr.: General 8 January 2013

United Nations S/2012/401 Security Council Distr.: General 8 January 2013 Original: English Identical letters dated 4 June 2012 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council Upon instructions from my Government, and following my letters dated 16 to 20 and 23 to 25 April, 7, 11, 14 to 16, 18, 21, 24, 29 and 31 May, and 1 and 4 June 2012, I have the honour to attach herewith a detailed list of violations of cessation of violence that were committed by armed groups in Syria on 3 June 2012 (see annex). It would be highly appreciated if the present letter and its annex could be circulated as a document of the Security Council. (Signed) Bashar Ja’afari Ambassador Permanent Representative 13-20354 (E) 170113 210113 *1320354* S/2012/401 Annex to the identical letters dated 4 June 2012 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council [Original: Arabic] Sunday, 3 June 2012 Rif Dimashq governorate 1. On 2/6/2012, from 1600 hours until 2000 hours, an armed terrorist group exchanged fire with law enforcement forces after the group attacked the forces between the orchards of Duma and Hirista. 2. On 2/6/2012 at 2315 hours, an armed terrorist group detonated an explosive device in a civilian vehicle near the primary school on Jawlan Street, Fadl quarter, Judaydat Artuz, wounding the car’s driver and damaging the car. -

S/2019/321 Security Council

United Nations S/2019/321 Security Council Distr.: General 16 April 2019 Original: English Implementation of Security Council resolutions 2139 (2014), 2165 (2014), 2191 (2014), 2258 (2015), 2332 (2016), 2393 (2017), 2401 (2018) and 2449 (2018) Report of the Secretary-General I. Introduction 1. The present report is the sixtieth submitted pursuant to paragraph 17 of Security Council resolution 2139 (2014), paragraph 10 of resolution 2165 (2014), paragraph 5 of resolution 2191 (2014), paragraph 5 of resolution 2258 (2015), paragraph 5 of resolution 2332 (2016), paragraph 6 of resolution 2393 (2017),paragraph 12 of resolution 2401 (2018) and paragraph 6 of resolution 2449 (2018), in the last of which the Council requested the Secretary-General to provide a report at least every 60 days, on the implementation of the resolutions by all parties to the conflict in the Syrian Arab Republic. 2. The information contained herein is based on data available to agencies of the United Nations system and obtained from the Government of the Syrian Arab Republic and other relevant sources. Data from agencies of the United Nations system on their humanitarian deliveries have been reported for February and March 2019. II. Major developments Box 1 Key points: February and March 2019 1. Large numbers of civilians were reportedly killed and injured in Baghuz and surrounding areas in south-eastern Dayr al-Zawr Governorate as a result of air strikes and intense fighting between the Syrian Democratic Forces and Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant. From 4 December 2018 through the end of March 2019, more than 63,500 people were displaced out of the area to the Hawl camp in Hasakah Governorate. -

IDP Camps in Northern Rural Aleppo, Fact Sheet.Pdf

IDP Camps in Northern Rural Aleppo, Fact Sheet www.stj-sy.com IDP Camps in Northern Rural Aleppo, Fact Sheet 58 IDPs and Iraqi refugees’ camps are erected in northern rural Aleppo, controlled by the armed opposition groups, the majority of which are suffering from deplorable humanitarian conditions Page | 2 IDP Camps in Northern Rural Aleppo, Fact Sheet www.stj-sy.com Syrians for Truth and Justice/STJ recorded the presence of no less than 58 camps, random and regular, erected in northern rural Aleppo, which the armed Syrian opposition groups control. In these camps, there are about 37199 families, over 209 thousand persons, both displaced internally from different parts in Syria and Iraqi refugees. The camps spread in three main regions; Azaz, Jarabulus and Afrin. Of these camps, 41 are random, receiving no periodical aid, while residents are enduring humanitarian conditions that can be called the most overwhelming, compared to others, as they lack potable water and a sewage system, in addition to electricity and heating means. Camps Located in Jarabulus: In the region of Jarabulus, the Zaghroura camp is erected. It is a regular camp, constructed by the Turkish AFAD organization. It incubates 1754 families displaced from Homs province and needs heating services and leveling the roads between the tents. There are other 20 random camps, which receive no periodical aid. These camps are al- Mayadeen, Ayn al-Saada, al-Qadi, Ayn al-Baidah, al-Mattar al-Ziraai, Khalph al-Malaab, Madraset al-Ziraa, al-Jumaa, al-Halwaneh, al-Kno, al-Kahrbaa, Hansnah, Bu Kamal, Burqus, Abu Shihab, al-Malaab, al-Jabal and al-Amraneh. -

G Secto R Objective 1: Improve the Fo Od Security Status of Assessed Foo D Insecure Peo Ple by Emergency Humanita

PEOPLE IN NEED PEOPLE IN NEED SO1 RESPONSE JANUARY 2017 CYCLE 8 7m Food & Livelihood 9 7 6.3m 6.3m 6.3m 6.3m 6.3m million Assistance Million 5.01 ORIGIN Food Basket 6 Humanitarian Needs Overview (HNO) - 2017 SO1 6.16m 3.35 M 1.631.79 MM 5.96m 5.8m 5.89m 3.35m 1.63m Target 5.45m 5 From within Syria From neighbouring September 2015 8.7 Million 5.01m countries June 2016 9.4 Million WHOLE OF SYRIA 4 September 2016 9.0 Million 459,299 Cash and Voucher 3 LIFE SUSTAINING AND LIFE SAVING OVERALL TARGET JAN 2017 PLAN RESPONSE Reached FOOD ASSISTANCE (SO1) TARGET SO1 Food Basket, Cash & Voucher BENEFICIARIES Beneficiaries Food Basket, 2 Cash & Voucher - 7 Additionally, Bread - Flour and Ready to Eat Rations were also Provided 5.01 1 life sustaining MODALITIES AND Million 9 Million Million 0 Emergency 2 (72%) of SO1 Target AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC JAN BENEFICIARIES REACHED BY Response Million 291,911 Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP) - 2017 2.08million 1.79 M 36°0'0"E 38°0'0"E 40°0'0"E 42°0'0"E From within Syria From neighbouring Bread-Flour countries 7 Cizre- 1 g! 0 Kiziltepe-Ad Nusaybin-Al 2 T U R K E Y Darbasiyah Qamishli Peshkabour T U R K E Y g! g! g! Ayn al Arab Ceylanpinar-Ras Al Ayn Al Yaroubiya Islahiye Karkamis-Jarabulus g! - Rabiaa 635,144 g! g! Akcakale-Tall g! Bab As Abiad g! Emergency Response with 11,700 580,838 Salama Cobanbey g! Ready to Eat Ration From within Syria From neighbouring g! g! countries Reyhanli - A L --H A S A K E H Bab al Hawa g! N A L E P P O " A L E P P O 0 Karbeyaz ' 0 Yayladagi ° g! A R - R A Q Q A 6 g! A R - R A Q Q A 3 1,193,251 Women IID L E B L A T T A K IIA 1,374,537 2,567,787 Girls Female Beneciaries H A M A Mediterranean D E II R -- E Z -- Z O R Sea T A R T O U S II R A Q T A R T O U S Al Arida g! 1,081,796 Abu Men H O M S Kamal-Khutaylah H O M S g! 1,360,733 L E B A N O N 2,442,530 Boys N " Male Beneciaries 0 ' 0 ° 4 3 Masnaa-Jdeidet Yabous *Note: SADD is based on ratio of 49:51 for male/female due to lack of consistent data across UNDOF g! partners. -

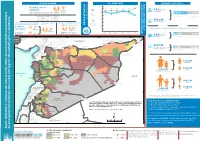

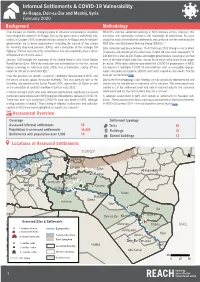

Informal Settlements & COVID-19 Vulnerability

Informal Settlements & COVID-19 Vulnerability Ar-Raqqa, Deir-ez-Zor and Menbij, Syria February 2020 Background Methodology Over the past six months, changing areas of influence and economic instability REACH’s informal settlement profiling in NES consists of key informant (KI) have shaped the context in Ar-Raqqa, Deir-ez-Zor governorates and Menbij sub- interviews with community members with knowledge of settlements. KIs were district. In October 2019, increased military activity in Ar-Raqqa and Al-Hasakeh sought for each of the informal settlements and collective centres verified by the governorates led to mass displacement (including the closure of two camps NES Sites and Settlements Working Group (SSWG).7; 8 for internally displaced persons (IDPs)) and a disruption of the strategic M4 Data collection took place between 19–27 February 2020 through a mix of direct 1 highway. Forced recruitment by armed forces has also reportedly been a driver (in-person) and remote (phone) interviews. In total, 98 sites were assessed in 12 2 of displacement in some areas. sub-districts in Deir-ez-Zor, Raqqa and Aleppo governorates, covering all verified January 2020 brought the expiration of the United Nations (UN) Cross Border sites at the time of data collection, except those which were found to no longer Resolution for Syria. While the resolution was extended for six months, several be active. While data collection pre-dated the COVID-19 preparations in NES, border crossings in northeast Syria (NES) lost authorisation, cutting off key this document highlights COVID-19 vulnerabilities such as susceptible groups, routes for UN aid to come into NES.3 water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) and health capacities and needs.