Prologue Géraldine Gourbe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Chronicle

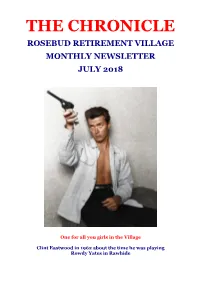

THE CHRONICLE ROSEBUD RETIREMENT VILLAGE MONTHLY NEWSLETTER JULY 2018 One for all you girls in the Village Clint Eastwood in 1962 about the time he was playing Rowdy Yates in Rawhide Message from Deb – July 2018 It was with much pleasure that we welcomed two new Residents to our Village in June. We send a very warm welcome to Eleanor Ashton and Margot O’Rourke. We do hope you settle in quickly to your new home and the Village and enjoy the variety of activities available. Residents will have noticed quite a bit of activity in the Village. Apologies if this is causing any inconvenience and at times deterring from the look of the Village. However, with various tradesmen, concrete trucks, deliveries and skips at least we can prove that the Village is on the improve. Currently there is various work being undertaken on seven Units, with another four scheduled to follow. I think this is a very exciting time and the Units are looking fabulous on completion. The building team is very efficient and cohesive and their work is of a high standard. They are also very obliging and helpful to deal with. The Resident Forum agreed to make changes to the garden entrance of the Village. I will be meeting with a representative from Wise Employment to have a Work for the Dole worker to assist with gardening works. A worker will be available for 25 hours a week over six months, with Eric Lee supervising the worker. My priorities are the entrance, the rockery, the lake area and a garden in Floral Court. -

Ben Bliss, Tenor Lachlan Glen, Piano Sat, Nov 5 / 3 PM / Hahn Hall

Corporate Season Sponsor: Ben Bliss, tenor Lachlan Glen, piano Sat, Nov 5 / 3 PM / Hahn Hall Program Strauss: John Gruen: Selections from Sechs Lieder von Adolf Friedrich Graf Spring is Like a Perhaps Hand von Schack, op. 17 from Three by E.E. Cummings Ständchen Lady will You Come with Me Into Nur Mut! from Three by E.E. Cummings Barkarole Lowell Liebermann: Ver Lieder, op. 27 The Arrow and the Song Morgen! from Six Songs on Poems of Henry W. Longfellow Boulanger: Theodore Chanler: Clairières dans le ciel I Rise When You Enter No. 4 - Un poète disait No. 7 - Nous nous aimerons tant Ned Rorem: No. 8 - Vous m’avez regardé avec toute votre âme Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening No. 9 - Les lilas qui avaient fleuri Eden Ahbez: Tosti: Nature Boy (Nat King Cole) Marechiare Harold Arlen and Johnny Mercer: - Intermission - One for My Baby (and One More for the Road) Britten: Ray Charles: The Children and Sir Nameless Hallelujah I Love Her So The Last Rose of Summer John Gruen’s works are provided courtesy of his daughter, Julia Gruen, The Choirmaster’s Burial (from Winter Words) to whom his Cummings cycle is dedicated. About the Program On today’s concert, our recitalists present a distinctly modern program spanning three languages, two hemispheres, and multiple genres, yet what differences we find in language and musical idiom are bridged by time: every compos- er featured in this recital lived and composed in the twentieth century. While the Strauss and Tosti selections were both written in the waning years of the nineteenth century, both composers bridged the gap between the two centu- ries, ushering in a new era of composition. -

BEAR FAMILY RECORDS TEL +49(0)4748 - 82 16 16 • FAX +49(0)4748 - 82 16 20 • E-MAIL [email protected]

BEAR FAMILY RECORDS TEL +49(0)4748 - 82 16 16 • FAX +49(0)4748 - 82 16 20 • E-MAIL [email protected] ARTIST Eden Ahbez TITLE Wild Boy The Lost Songs Of Eden Ahbez LABEL Bear Family Productions CATALOG # BAF 18018 PRICE-CODE BAF EAN-CODE ÇxDTRBAMy180187z FORMAT VINYL-album with gatefold sleeve • 180g vinyl GENRE Rock 'n' Roll / Tiki TRACKS 14 PLAYING TIME 37:26 G Hippie #1 G 14 rare/unreleased recordings G Guest appearances by Paul Horn, Eartha Kitt, and more G 180 gram vinyl G Fully annotated, with never before seen pictures INFORMATION By now psychedelic music is a mainstay of popular taste. But questions of its origins still linger. As such, BEAR FAMILY RECORDS now submits 'Wild Boy: The Lost Songs Of Eden Ahbez' as fresh evidence in the quest for answers. Over the past twenty years Ahbez has gone from cult figure to harbinger of the Sixties flower-power movement. This notion is born out largely by his 1948 ant- hem of universal love, Nature Boy, and his rare solo album from 1960, titled 'Eden's Island' – one of popular music's earliest con- cept albums. 'Wild Boy: The Lost Songs Of Eden Ahbez' both expands the Ahbez catalog and deepens the notion of a psychedelic movement having roots in the 1950s. Side one acts as a compilation of music that Ahbez wrote in the aftermath of Nature Boy. Inclusion of songs like Palm Springs by the Ray Anthony Orchestra and Hey Jacque by Eartha Kitt give listeners the chance to hear obscure cuts by big-name artists in the context of Ahbez for the first time. -

Alumni Journal Alumni Journal 1-8Oo-SUALUMS (782-5867)

et al.: Alumni Journal Alumni Journal www.syr.edu/alumni 1-8oo-SUALUMS (782-5867) Staying in Touch s Chancellor Nancy Cantor completes her inaugu Aral year, the Office of Alumni Relations has been busy keeping alumni up to date with all the exciting developments at Syracuse University. From traveling abroad and cultivating relationships in new territo ries, to establishing new partnerships in Central New York, this has really been a year of change. At the Office of Alumni Relations, we strive to keep alumni informed of SU news and new happen ings that are taking place both on and off campus. Along with updates provided by Syracuse University Magazine, we send a monthly electronic newsletter, Orangebytes, to keep alumni current on campus information. If you are not receiving Orangebytes, send us an e-mail at sualumni@syr. edu. You can also update your information at the SU Online Community , The Importance of Being Otto (visit our web site at www.syr.edu/alumm}, where you ' is voice is silent, but his colors are loud and his actions boisterous. He can connect to SU alumni and stay in close touch with Hrepresents pride, athleticism-and fun. Otto the Orange, SU's official your alma mater no matter where you reside. mascot, is well loved among SU fans and friends and is gaining recogni The changes and exciting events this past year tion through national commercial spots and championship games. Those are only the beginning of what is sure to be an who know the jovial, rotund orange character with the jaunty cap and amazing time in SU's history as Chancellor Cantor's friendly wave understand his appeal. -

Fall 2010 1 INDEPENDENT PUBLISHERS GROUP – FALL 2010 New Titles

INDEPENDENT PUBLISHERS GROUP Fall 2010 1 INDEPENDENT PUBLISHERS GROUP – FALL 2010 New Titles A Glee-ful salute for the legions of “gleeks” who can’t get enough of this new hit show Don’t Stop Believin’ The Unofficial Guide to Glee Erin Balser and Suzanne Gardner • $20,000 marketing budget; co-op available • Glee was the most successful new show of the 2009 television season, winning the Golden Globe Award for Best Television Series—Musical or Comedy and the Screen Actors Guild Award for Outstanding Performance by an Ensemble in a Comedy Series • The final episode of Glee’s first season was watched by 8.9 million American viewers The fictional high school milieu of Glee—the wildly popular Fox television series that debuted in 2009—is celebrated and dissect- ed in this detailed companion to the series. The songs, the stu- dents, and the idiosyncratic teachers all come under affectionate scrutiny in this fan’s compendium. The familiar dramas that beset the members of the McKinley High glee club, New Directions, have struck a chord with a wide audience that ranges from tweens to 20-somethings and beyond. Glee watchers will relish this analysis of every relationship, fashion statement, insult, and triumph that is plumbed for greater meaning and nos- talgic pleasure. The music that is such a key element of the show—a careful mix of show tunes and popular hits—is also thoughtfully discussed. Trivia, in-jokes, profiles of the actors, and a detailed synopsis of the show’s first season make this an indis- pensable reference for the growing fan base of “gleeks” that are devoted to this fledgling television sensation. -

History of Erewhon 1

HISTORY OF EREWHON 1 HISTORY OF EREWHON - NATURAL FOODS PIONEER IN THE UNITED STATES (1966-2011): EXTENSIVELY ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY AND SOURCEBOOK Copyright © 2011 by Soyinfo Center HISTORY OF EREWHON 2 Copyright © 2011 by Soyinfo Center HISTORY OF EREWHON 3 HISTORY OF EREWHON - NATURAL FOODS PIONEER IN THE UNITED STATES (1966-2011): EXTENSIVELY ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY AND SOURCEBOOK Compiled by William Shurtleff & Akiko Aoyagi 2011 Copyright © 2011 by Soyinfo Center HISTORY OF EREWHON 4 Copyright (c) 2011 by William Shurtleff & Akiko Aoyagi All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means - graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or information and retrieval systems - except for use in reviews, without written permission from the publisher. Published by: Soyinfo Center P.O. Box 234 Lafayette, CA 94549-0234 USA Phone: 925-283-2991 Fax: 925-283-9091 www.soyinfocenter.com [email protected] ISBN 978-1-928914-33-4 (History of Erewhon) Printed 2011 April 4; revised and enlarged 2011 April 30 Price: Available on the Web free of charge Search engine keywords: Erewhon Trading Co. Erewhon Trading Company Erewhon Inc. Erewhon, Inc. Copyright © 2011 by Soyinfo Center HISTORY OF EREWHON 5 Contents Page Dedication and Acknowledgments .............................................................................................................................. 6 Preface, by James Silver ............................................................................................................................................. -

"A" - You're Adorable (The Alphabet Song) 1948 Buddy Kaye Fred Wise Sidney Lippman 1 Piano Solo | Twelfth 12Th Street Rag 1914 Euday L

Box Title Year Lyricist if known Composer if known Creator3 Notes # "A" - You're Adorable (The Alphabet Song) 1948 Buddy Kaye Fred Wise Sidney Lippman 1 piano solo | Twelfth 12th Street Rag 1914 Euday L. Bowman Street Rag 1 3rd Man Theme, The (The Harry Lime piano solo | The Theme) 1949 Anton Karas Third Man 1 A, E, I, O, U: The Dance Step Language Song 1937 Louis Vecchio 1 Aba Daba Honeymoon, The 1914 Arthur Fields Walter Donovan 1 Abide With Me 1901 John Wiegand 1 Abilene 1963 John D. Loudermilk Lester Brown 1 About a Quarter to Nine 1935 Al Dubin Harry Warren 1 About Face 1948 Sam Lerner Gerald Marks 1 Abraham 1931 Bob MacGimsey 1 Abraham 1942 Irving Berlin 1 Abraham, Martin and John 1968 Dick Holler 1 Absence Makes the Heart Grow Fonder (For Somebody Else) 1929 Lewis Harry Warren Young 1 Absent 1927 John W. Metcalf 1 Acabaste! (Bolero-Son) 1944 Al Stewart Anselmo Sacasas Castro Valencia Jose Pafumy 1 Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive 1944 Johnny Mercer Harold Arlen 1 Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive 1944 Johnny Mercer Harold Arlen 1 Accidents Will Happen 1950 Johnny Burke James Van Huesen 1 According to the Moonlight 1935 Jack Yellen Joseph Meyer Herb Magidson 1 Ace In the Hole, The 1909 James Dempsey George Mitchell 1 Acquaint Now Thyself With Him 1960 Michael Head 1 Acres of Diamonds 1959 Arthur Smith 1 Across the Alley From the Alamo 1947 Joe Greene 1 Across the Blue Aegean Sea 1935 Anna Moody Gena Branscombe 1 Across the Bridge of Dreams 1927 Gus Kahn Joe Burke 1 Across the Wide Missouri (A-Roll A-Roll A-Ree) 1951 Ervin Drake Jimmy Shirl 1 Adele 1913 Paul Herve Jean Briquet Edward Paulton Adolph Philipp 1 Adeste Fideles (Portuguese Hymn) 1901 Jas. -

EDEN Mauro Grossi

EDEN Mauro Grossi Progetto di composizioni originali basate sul brano “Nature Boy” in forma di Tema e Variazioni uscito in cd il 18 ottobre per l'etichetta Abeat. Un lavoro concettuale con trama e motivazioni, coraggioso e poetico in grado di approfondire le innumerevoli implicazioni strutturali di questa fenomenale canzone dovuta ad un autore sorprendente e influente come Eden Ahbez. Il progetto Eden propone un nuovo e creativo approccio agli standard, lontano da qualunque tipo di revival e si configura anche come uno dei più lunghi atti musicali d'amore di cui si abbia notizia: l'amore di Mauro Grossi per un brano che celebra l'amore, intendendo "tolleranza e rispetto", come valori primari. Per questo motivo ogni brano presentato, appartenendo ad uno stile diverso, da un suo apporto specifico, ma trae senso e vantaggi dall'accostamento agli altri. Infatti, benchè tutti originali, i brani hanno un'unica radice, della quale sono variazioni sempre più evolute ed emancipate. Proprio come esseri umani. (continua) Mauro Grossi piano, celesta, arrangiamenti, direzione Claudia Tellini voce Nico Gori clarinetto, clarinetto basso, sax soprano Andrea Dulbecco vibrafono Ares Tavolazzi contrabbasso Walter Paoli batteria, percussioni Possibilità di avere la sezione d'archi in concerto. Estratti dalle prime recensioni pubblicate. “ Bizzarro: un album interamente dedicato alla celebrazione di un unico brano. E' un segno dello straordinario amore da parte del suo ideatore, il pianista Mauro Grossi per una delle composizioni più belle mai scritte non solo in ambito Jazz “Nature Boy”.... Grossi ha elaborato/composto una fantastica serie di variazioni basate sulla melodia di questo meraviglioso pezzo e quindi è possibile ascoltare “Nature Boy” nei contesti più disparati... -

A Bewitching Realm Reopens Tahquitz Canyon Had Been

TAahBqeuwitzitCchaninyognRHeaadlBmeeRn eShoapnegrni-s La to Hippies, Hermits and Evil Spirits. For Decades Its Dangers Made It Off-Limits. Now the ‘NoTrespassing’ Signs Are Coming Down. Los Angeles Times Magazine, Jan 14, 2001 By Ann Japenga SEVERAL YEARS AGO, I WAS LUGGING BOXES into my new Palm Springs home and needed a break from unpacking. Parking my car not far from the spritzing misters downtown, I walked up the flood-control channel toward a massive gash, a door into the mountains: Tahquitz Canyon. Coming toward me down the trail was a lone man. At first I was happy to encounter another hiker, but as he got closer, I picked up an unmistakable scent of evil. He glared at me sideways out of psychotic blue eyes, spraying sweat and spitting out a malicious incantation. A few months later I saw a mug shot of the same fellow in the paper and read that he’d tried to push a group of hikers off a precipice into the canyon. I felt lucky to have survived the man’s wrath, of course, but more than that I felt privileged, as a newcomer, to have met the wrathful spirit of Tahquitz. It was like attending the ultimate insider bash your first week in town. I’d known—in some vague, folkloric way—about the curse of Tahquitz my whole life. Growing up in the San Gabriel Valley, I simply assimilated the notion that there was an awesome canyon out in Palm Springs and weird things happened there. California kids know this. “ere are a thousand stories up there,” affirms helicopter pilot Steve de Jesus, who has assisted in many Tahquitz rescues. -

Jazz & Tonic Pacific Standard Time

SPECIAL THANKS TO OUR 2012-2013 DONORS Founders Circle ($10,000 and above) Friends ($100 - $499) Regena Cole and the Bob Cole Foundation Biola University Music at Noon The Ella Fitzgerald Charitable Foundation Margot Coleman Stuart Hubbard & Carol Mac Gregor Season Sponsors ($5,000 - $9,999) Lavonne McQuilkin CSULB Alumni Association Mr. & Mrs. Donald Seidler David Wuertele & Tomoko Shimaya Director’s Circle ($1,000 - $4,999) Mr. & Mrs. Charlie Tickner MiraCosta College / Oceanside Vocal Jazz Festival Supporters ($20 - $99) Mike & Erin Mugnai (in kind donation) Louise Reed Mr. & Mrs. Robert Swoish Karin Reilly Patrons ($500 - $999) PACIFIC St. Gregory’s Episcopal Church of Long Beach PERSONNEL STANDARD TIME JAZZ & TONIC PACIFIC STANDARD TIME CHRISTINE GUTER, DIRECTOR Glynis Davies, Director Christine Guter, Director Bradley Allen Marcus Carline Steven Amie Glynis Davies * Emily Jackson ^ Jonathan Eastly Arend Jessurun Ashlyn Grover * Alyssa Keyne Joe Sanders Katrina Kochevar Maria Schafer Jake Lewis Miko Shudo JAZZ & TONIC Christine Li Scott Leeav Sofer ^ + Molly McBride Rachel St. Marseille ^ * Patricia Muresan Jenny Swoish Emilio Tello ^ Jake Tickner Jordan Tickner Riley Wilson GLYNIS DAVIES, DIRECTOR Piano – Anthony Escoto Piano – Kyle Schafer Bass – Daniel Reasoner ^ Bass – Chelsea Stevens Drums – Tyler Kreutel Drums – Brett Kramer ^ FRIDAY, APRIL 19, 2013 ^ Section Leader * Ella Fitzgerald Scholar + Cole Scholar 8:00PM For ticket information please call 562.985.7000 or visit the web at: UNIVERSITY THEATRE PLEASE SILENCE ALL ELECTRONIC MOBILE DEVICES. This concert is funded in part by the INSTRUCTIONALLY RELATED ACTIVITIES FUNDS (IRA) provided by California State University, Long Beach. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To build a strong program at the Bob Cole Conservatory, we must attract the PROGRAM finest young jazz talent. -

February 9-19, 2021

SAVANNAH'S WEEK LONG CELEBRATION OF SONG FEBRUARY 9-19, 2021 AMERICANTRADITIONSCOMPETITION.COM All events will begin at 7pm on the date listed, and remain available to watch at the audience’s leisure until February 28, 2021. TUESDAY FEB. 9 Quarterfinal 1 Sponsored by Tricia & David Guggenheim WEDNESDAY FEB. 10 Quarterfinal 2 Sponsored by Kathie & Les Anderson THURSDAY FEB. 11 Quarterfinal 3 pro Sponsored by Nancy McGirr & David Goslin FRIDAY FEB. 12 Quarterfinal 4 Sponsored by Patty & Heyward Gignilliat TUESDAY FEB. 16 Judges Concert Sponsored by The Charles C. Taylor and Samir gram Nikocevic Charitable Foundation WEDNESDAY FEB. 17 Semifinal 1 Sponsored by Hedy & Michael Fawcett THURSDAY FEB. 18 Semifinal 2 flow Sponsored by Danny Cohen FRIDAY FEB. 19 Final Round Sponsored by Savannah Morning News 14 ATC PRESIDENT 15 ATC DIRECTOR 16 ABOUT THE ATC ATC BOARD OF DIRECTORS EDUCATIONAL OUTREACH 17 JUNIOR ATC 18 IN-KIND DONATIONS of 19 VOLUNTEERS table 20 ATC DONORS 22 AWARDS 24 PAST GOLD MEDAL WINNERS 25 SPONSORS 26 2021 JUDGES cont 28 PIANISTS 29 INSTRUMENTALISTS 30 2021 CONTESTANTS ents W E C R E A T E D Y N A M I C V I D E O C O N T E N T F O R B U S I N E S S A N D C R E A T I V E P L A T F O R M S . S A V A N N A H , G A 3 1 4 0 1 | 7 0 6 . 4 4 9 . 1 2 1 2 WELCOME TO THE 28TH YEAR OF ATC A N O T E F R O M A T C B O A R D P R E S I D E N T Greetings all. -

Download Download

Author: Carter, Dale; Title: Surf Aces Resurfaced: The Beach Boys and the Greening of the American Counterculture, 1963-1973 Surf Aces Resurfaced: The Beach Boys and the Greening of the American Counterculture, 1963-1973 Dale Carter Aarhus University Abstract The rise of the American counterculture between the early- to mid-1960s and early- to mid-1970s was closely associated with the growth of environmentalism. This article explores how both informed popular music, which during these years became not only a prominent form of entertainment but also a forum for cultural and social criticism. In particular, through contextual and lyrical analyses of recordings by The Beach Boys, the article identifies patterns of change and continuity in the articulation of countercultural, ecological, and related sensibilities. During late 1966 and early 1967, the group’s leader Brian Wilson and lyricist Van Dyke Parks collaborated on a collection of songs embodying such progressive thinking, even though the music of The Beach Boys had previously shown no such ambitions. In the short term, their efforts floundered as the risk- averse logic of the commercial music industry prompted group members to resist perceived threats to their established profile. Yet in the long term (and ironically in the name of commercial survival), The Beach Boys began selectively to adopt innovations they had previously shunned. Shorn of its more controversial associations, what had formerly been considered high risk had by 1970 become good business as once-marginal environmentalism gained broader acceptability: thus did ‘America’s band’ articulate the flowering, greening, and fading of the counterculture. Keywords: popular music, ecology, counterculture, Beach Boys Resumen Vol 4, No 1 El auge de la contracultura americana entre principios y mediados de las décadas de 1960 y 1970 guarda una estrecha relación con la expansión del movimiento ecologista.