Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Good Vibrations Sessions. from Came Our Way on Cassette from California, and We “Unsurpassed Masters Vol

Disc 2 231. George Fell Into His French Horn 201. Good Vibrations Sessions The longest version yet heard, and in stereo. This Tracks 1 through 28 - Good Vibrations Sessions. From came our way on cassette from California, and we “Unsurpassed Masters Vol. 15”, but presenting only the last, digitally de-hissed it. best and most complete attempt at each segment. 232. Vegetables (Alternate lyric and arrangement) Track 202. Good Vibrations Sessions Another track from the California cassettes. This Track 203. Good Vibrations Sessions version has significant lyric and arrangement Track 204. Good Vibrations Sessions differences. Track 205. Good Vibrations Sessions Track 206. Good Vibrations Sessions 233. Surf’s Up Sessions Track 207. Good Vibrations Sessions While not full fidelity, this has the best sound yet, Track 208. Good Vibrations Sessions and a bit of humorous dialogue between Brian Track 209. Good Vibrations Sessions Wilson and session bassist Carol Kaye. From the Track 210. Good Vibrations Sessions California cassetes, and now digitally de-hissed. Track 211. Good Vibrations Sessions Track 212. Good Vibrations Sessions 234. Wonderful Track 213. Good Vibrations Sessions Beach Boys incomplete vocal attempt. Track 214. Good Vibrations Sessions Track 215. Good Vibrations Sessions 235. Child is Father to The Man Track 216. Good Vibrations Sessions Beach Boys incomplete vocal attempt. Tracks 234 Track 217. Good Vibrations Sessions and 235 are from the Japanese “T-2580” “Smile” Track 218. Good Vibrations Sessions bootleg and now digitally de-hissed. Track 219. Good Vibrations Sessions Track 220. Good Vibrations Sessions 236. Heroes & Villains Part Two (Original mono Track 221. Good Vibrations Sessions mix) Track 222. -

Brian Wilson's Spacious Estate in West Suburban St

May 24, 1998---- The backyard of Brian Wilson's spacious estate in west suburban St. Charles overlooks a calm pond. A playground set stands near the water. Wilson slowly walks out of the basement studio in the home he shares with wife Melinda and daughters Daria, 2, and Delanie, 6 months old. Wilson squints into the midday sun. He looks at a playground slide. Then he looks at a swing set. Wilson elects to sit down on the saddle swing. In a life of storied ups and downs, Wilson's career is on the upswing. The June release of ``Imagination'' (Giant Records) is a return to 1966's ``Pet Sounds'' in terms of orchestration and instrumentation, with its the ambitious patterns of tympanies and snare drums. But equally important are Wilson's vocals, which are the smoothest and most soulful since 1970's ``Sunflower.'' Wilson, 55, has suddenly defied age. Mick Jagger and Pete Townshend are brittle rock 'n' roll barnacles. Ray Davies and Paul McCartney have matured gracefully. Yet here's Wilson singing with effervescent hope on ``Dream Angel,'' which he co-wrote with his co-producer Joe Thomas and Jim Peterik of Survivor and Ides of March fame. The song was inspired by Wilson's new daughters. They make him happy. He says that is why he is writing happy music. On ``Dream Angel,'' Wilson even returned to the tight, late '50s harmonies of the Dell Vikings (``Come Go With Me'') and the Four Freshmen - happy-go-lucky voices that influenced the Beach Boys when they were young. -

Meet Our 2018 El Camino College Distinguished Alumni

Meet our 2018 El Camino College Distinguished Alumni The El Camino College Foundation is proud to announce the 2018 Distinguished Alumni. These individuals have furthered their educational and career goals and have proven to be outstanding in their field, as well as recognized for achievements in business, volunteerism and philanthropy. Distinguished Alumni Award We’re proud to announce that we will also honor one area EL CAMINO COLLEGE philanthropist and one local corporate partner with the first ever 2018 Distinguished Alumni Gratitude Awards. This award recognizes long time support of El Camino & Gratitude Awards Dinner students to help ensure they have a more successful and productive educational experience. Please join us to celebrate and recognize these Friday, February 1, 2019 6:00 pm deserving recipients. Torrance Marriott For more details visit www.elcaminocollegefoundation.org Rocky Chavez Dan Keenan Sherry Kramer Brian Wilson Assemblymember Dan Keenan Sherry Kramer Brian Wilson Rocky Chavez Gratitude Award Recipients Dan Keenan is Senior Vice President Since 2006, Sherry Kramer has Brian Wilson is most famously Rocky Chávez began his career in at Keenan & Associates in Torrance and been the Director of Community Affairs known as the founder of the Beach Frances Ford public service after graduating from works closely with public agencies and and Government Relations for Continental Boys, an iconic American band that Frances Ford has a passion for helping students at El Camino El Camino College and then Chico State, Keenan & Associates benefit consultants Development Corporation, a commercial created the sounds of Southern College. Her late husband Warren was a Chemistry professor for 36 when he joined the United States Marine to design and implement retirement real estate business which also includes California. -

Catch a Wave: the Rise, Fall and Redemption of the Beach Boys Brian Wilson Pdf

FREE CATCH A WAVE: THE RISE, FALL AND REDEMPTION OF THE BEACH BOYS BRIAN WILSON PDF Peter Ames Carlin | 368 pages | 06 Aug 2007 | RODALE PRESS | 9781594867491 | English | Pennsylvania, United States Catch a Wave by Peter Ames Carlin - PopMatters Superhero media has a history of critiquing the dark side of power, hero worship, and vigilantism, but none have done so as radically as Watchmen and The Boys. Aussie indie rockers, Floodlights' debut From a View is a very cleanly, crisply-produced and mixed collection of shambolic, do-it- yourself indie guitar music. CF Watkins has pulled off the Catch a Wave: The Rise trick of creating an album that is imbued with the warmth of the American South as well as the urban sophistication of New York. Canadian singer-songwriter Helena Deland's first full-length release Someone New reveals her considerable creative talents. Joe Wong, the composer behind Netflix's Russian Doll and Master of Nonearticulates personal grief and grappling with artistic fulfillment into a sweeping debut album. British rocker Peter Frampton grew up fast before reaching meteoric heights with Frampton Comes Alive! Now the year- old Grammy-winning artist facing a degenerative muscle condition looks back on his life in his new memoir and this revealing interview. Bishakh's Som's graphic memoir, Spellboundserves as a reminder that trans memoirs need not hinge on transition narratives, or at least not on the ones we are used to seeing. Seductively approachable, Gamblers' sunny sound masks the tragedy and despair that populate the band's debut album. Peter Guralnick's homage to writing about music, 'Looking to Get Lost', shows Catch a Wave: The Rise good music writing gets the music into the readers' head. -

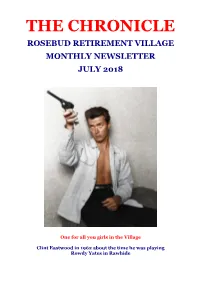

The Chronicle

THE CHRONICLE ROSEBUD RETIREMENT VILLAGE MONTHLY NEWSLETTER JULY 2018 One for all you girls in the Village Clint Eastwood in 1962 about the time he was playing Rowdy Yates in Rawhide Message from Deb – July 2018 It was with much pleasure that we welcomed two new Residents to our Village in June. We send a very warm welcome to Eleanor Ashton and Margot O’Rourke. We do hope you settle in quickly to your new home and the Village and enjoy the variety of activities available. Residents will have noticed quite a bit of activity in the Village. Apologies if this is causing any inconvenience and at times deterring from the look of the Village. However, with various tradesmen, concrete trucks, deliveries and skips at least we can prove that the Village is on the improve. Currently there is various work being undertaken on seven Units, with another four scheduled to follow. I think this is a very exciting time and the Units are looking fabulous on completion. The building team is very efficient and cohesive and their work is of a high standard. They are also very obliging and helpful to deal with. The Resident Forum agreed to make changes to the garden entrance of the Village. I will be meeting with a representative from Wise Employment to have a Work for the Dole worker to assist with gardening works. A worker will be available for 25 hours a week over six months, with Eric Lee supervising the worker. My priorities are the entrance, the rockery, the lake area and a garden in Floral Court. -

Seize the Season with Golden Nugget's Fully Loaded Fall Events

* MEDIA ALERT * Seize the Season with Golden Nugget’s Fully Loaded Fall Events Calendar Calling all fun-seekers: A schedule of grub, booze, and entertainment to cozy up to this cool, colorful autumn WHAT: Beginning Tuesday, September 5, the Golden Nugget Casino, Hotel & Marina invites shore goers to shed the end-of-summer sadness and embrace the best in upcoming entertainment—chunky sweaters optional. In addition to top performers, the autumn schedule brings festivities with a generous mix of tasty fare and enticing fun, swapping out the summer scene for a fresh fall spin on outings at the shore. For more information on Golden Nugget’s 2017 fall events calendar, please visit: http://www.goldennugget.com/atlantic-city/entertainment/ WHO: Tuesday, September 5 - Sunday, December 31 Golden Gridiron Competitive participants can fill their pockets as Golden Nugget gives away over $250,000 in Cash and Free Play over the 17-week 2017 Football season. Picks can be made every Tuesday through Sunday before 12 PM for a chance at the weekly prize. Thursday, September 7 - Sunday, September 10 Boat Show Boat connoisseurs can expect the hottest new yachts, cruisers, sport fish and more, with the best deals in the maritime market at the 2017 In-Water Power Boat Show. While checking the latest styles and trends, Yachties can also refuel while listening to live music on the marina deck. Adult admission is $15 and all children under 12 are free! Saturday, September 16 Craft Beer Festival Attendees can sample over 99 varieties of seasonal craft beers from over 30 different breweries, paired with chef-inspired appetizers and live entertainment by Seven Stone. -

“My Little Deuce Coupe” by the Beach Boys

“My little deuce coupe” by the Beach Boys Little deuce Coupe You don`t know what I got Little deuce Coupe You don`t know what I got Well I`m not braggin` babe so don`t put me down• But I`ve got the fastest set of wheels in town When something comes up to me he don`t even try Cause if I had a set of wings man I know she could fly She`s my little deuce coupe You don`t know what I got (My little deuce coupe) (You don`t know what I got) Just a little deuce coupe with a flat head mill But she`ll walk a Thunderbird like (she`s) it`s standin` still She`s ported and relieved and she`s stroked and bored. She`ll do a hundred and forty with the top end floored She`s my little deuce coupe You don`t know what I got (My little deuce coupe) (You don`t know what I got) She`s got a competition clutch with the four on the floor And she purrs like a kitten till the lake pipes roar And if that aint enough to make you flip your lid There`s one more thing, I got the pink slip daddy And comin` off the line when the light turns green Well she blows `em outta the water like you never seen I get pushed out of shape and it`s hard to steer When I get rubber in all four gears She`s my little deuce coupe You don`t know what I got She`s ported and relieved and she`s stroked and bored. -

Walt Whitman, John Muir, and the Song of the Cosmos Jason Balserait Rollins College, [email protected]

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Master of Liberal Studies Theses Spring 2014 The niU versal Roar: Walt Whitman, John Muir, and the Song of the Cosmos Jason Balserait Rollins College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Balserait, Jason, "The nivU ersal Roar: Walt Whitman, John Muir, and the Song of the Cosmos" (2014). Master of Liberal Studies Theses. 54. http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls/54 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Liberal Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Universal Roar: Walt Whitman, John Muir, and the Song of the Cosmos A Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Liberal Studies by Jason A. Balserait May, 2014 Mentor: Dr. Steve Phelan Reader: Dr. Joseph V. Siry Rollins College Hamilton Holt School Master of Liberal Studies Program Winter Park, Florida Acknowledgements There are a number of people who I would like to thank for making this dream possible. Steve Phelan, thank you for setting me on this path of self-discovery. Your infectious love for wild things and Whitman has changed my life. Joe Siry, thank you for support and invaluable guidance throughout this entire process. Melissa, my wife, thank you for your endless love and understanding. I cannot forget my two furry children, Willis and Aida Mae. -

I AM BRIAN WILSON Brian Wilson October 11Th, 2016

I AM BRIAN WILSON Brian Wilson October 11th, 2016 OVERVIEW: As a cofounding member of The Beach Boys in the 1960s, Brian Wilson created some of the most groundbreaking and timeless music ever recorded. Derailed in the 1970s by mental illness, excessive drug use, and the shifting fortunes of the band’s popularity, Wilson came back again and again over the next few decades, surviving and ultimately thriving. In his memoir entitled I Am Brian Wilson, he details the exhilarating highs and lows of his life from his failing memory, including the sources of his creative inspiration throughout the decades. - - - - - - - - - EARLY LIFE: Brian Wilson was born on June 20th, 1942 to Audree and Murry Wilson. Growing up in Hawthorne, California, Wilson exhibited unusual musical abilities, such as being able to hum the melody from When the Caissons Go Rolling Along after only a few verses had been sung by his father before the age of one. Surprisingly, a few years later, he was discovered to have diminished hearing in his right ear. The exact cause of this hearing loss is unclear, though theories range from him simply being born partially deaf to a blow to the head from his father, or a neighborhood bully, being to blame. While Wilson’s father was a reasonable provider, he was often abusive. A minor musician and songwriter, he also encouraged his children in this field in numerous ways. At an early age, Brian was given six weeks of lessons on a toy accordion and, at seven and eight, sang solos in church with a choir. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

Ben Bliss, Tenor Lachlan Glen, Piano Sat, Nov 5 / 3 PM / Hahn Hall

Corporate Season Sponsor: Ben Bliss, tenor Lachlan Glen, piano Sat, Nov 5 / 3 PM / Hahn Hall Program Strauss: John Gruen: Selections from Sechs Lieder von Adolf Friedrich Graf Spring is Like a Perhaps Hand von Schack, op. 17 from Three by E.E. Cummings Ständchen Lady will You Come with Me Into Nur Mut! from Three by E.E. Cummings Barkarole Lowell Liebermann: Ver Lieder, op. 27 The Arrow and the Song Morgen! from Six Songs on Poems of Henry W. Longfellow Boulanger: Theodore Chanler: Clairières dans le ciel I Rise When You Enter No. 4 - Un poète disait No. 7 - Nous nous aimerons tant Ned Rorem: No. 8 - Vous m’avez regardé avec toute votre âme Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening No. 9 - Les lilas qui avaient fleuri Eden Ahbez: Tosti: Nature Boy (Nat King Cole) Marechiare Harold Arlen and Johnny Mercer: - Intermission - One for My Baby (and One More for the Road) Britten: Ray Charles: The Children and Sir Nameless Hallelujah I Love Her So The Last Rose of Summer John Gruen’s works are provided courtesy of his daughter, Julia Gruen, The Choirmaster’s Burial (from Winter Words) to whom his Cummings cycle is dedicated. About the Program On today’s concert, our recitalists present a distinctly modern program spanning three languages, two hemispheres, and multiple genres, yet what differences we find in language and musical idiom are bridged by time: every compos- er featured in this recital lived and composed in the twentieth century. While the Strauss and Tosti selections were both written in the waning years of the nineteenth century, both composers bridged the gap between the two centu- ries, ushering in a new era of composition. -

The Beach Boys 100.Xlsx

THE BEACH BOYS 100 Rank Songs 1 Good Vibrations 2 California Girls 3 God Only Knows 4 Caroline No 5 Don't Worry Baby 6 Fun Fun Fun 7 I Get Around 8 Surfin' USA 9 Til I Die 10 Wouldn't It Be Nice 11 I Just Wasn't Made for These Times 12 Warmth of the Sun 13 409 14 Do You Remember 15 A Young Man is Gone 16 When I Grow Up 17 Come Go With Me 18 Girl from New York City 19 I Know There's an Answer 20 In My Room 21 Little Saint Nick 22 Forever 23 Surfin' 24 Dance Dance Dance 25 Let Him Run Wild 26 Darlin' 27 Rock & Roll to the Rescue 28 Don't Back Down 29 Hang on to your Ego 30 Sloop John B 31 Wipeout (w/ The Fat Boys) 32 Wild Honey 33 Friends 34 I'm Waiting for the Day 35 Shut Down 36 Little Deuce Coupe 37 Vegetables 38 Sail On Sailor 39 I Can Hear Music 40 Heroes & Villains 41 Pet Sounds 42 That's Not Me 43 Custom Machine 44 Wendy 45 Breakaway 46 Be True to Your School 47 Devoted to You 48 Don't Talk 49 Good to My Baby 50 Spirit of America 51 Let the Wind Blow THE BEACH BOYS 100 52 Kokomo 53 With Me Tonight 54 Cotton Fields 55 In the Back of My Mind 56 We'll Run Away 57 Girl Don't Tell Me 58 Surfin' Safari 59 Do You Wanna Dance 60 Here Today 61 A Time to Live in Dreams 62 Hawaii 63 Surfer Girl 64 Rock & Roll Music 65 Salt Lake City 66 Time to Get Alone 67 Marcella 68 Drive-In 69 Graduation Day 70 Wonderful 71 Surf's Up 72 Help Me Rhonda 73 Please Let Me Wonder 74 You Still Believe in Me 75 You're So Good to Me 76 Lonely Days 77 Little Honda 78 Catch a Wave 79 Let's Go Away for Awhile 80 Hushabye 81 Girls on the Beach 82 This Car of Mine 83 Little Girl I Once Knew 84 And Your Dreams Come True 85 This Whole World 86 Then I Kissed Her 87 She Knows Me Too Well 88 Do It Again 89 Wind Chimes 90 Their Hearts Were Full of Spring 91 Add Some Music to Your Day 92 We're Together Again 93 That's Why God Made Me 94 Kiss Me Baby 95 I Went to Sleep 96 Disney Girls 97 Busy Doin' Nothin' 98 Good Timin' 99 Getcha Back 100 Barbara Ann.