Ben Bliss, Tenor Lachlan Glen, Piano Sat, Nov 5 / 3 PM / Hahn Hall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Chronicle

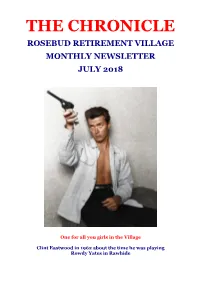

THE CHRONICLE ROSEBUD RETIREMENT VILLAGE MONTHLY NEWSLETTER JULY 2018 One for all you girls in the Village Clint Eastwood in 1962 about the time he was playing Rowdy Yates in Rawhide Message from Deb – July 2018 It was with much pleasure that we welcomed two new Residents to our Village in June. We send a very warm welcome to Eleanor Ashton and Margot O’Rourke. We do hope you settle in quickly to your new home and the Village and enjoy the variety of activities available. Residents will have noticed quite a bit of activity in the Village. Apologies if this is causing any inconvenience and at times deterring from the look of the Village. However, with various tradesmen, concrete trucks, deliveries and skips at least we can prove that the Village is on the improve. Currently there is various work being undertaken on seven Units, with another four scheduled to follow. I think this is a very exciting time and the Units are looking fabulous on completion. The building team is very efficient and cohesive and their work is of a high standard. They are also very obliging and helpful to deal with. The Resident Forum agreed to make changes to the garden entrance of the Village. I will be meeting with a representative from Wise Employment to have a Work for the Dole worker to assist with gardening works. A worker will be available for 25 hours a week over six months, with Eric Lee supervising the worker. My priorities are the entrance, the rockery, the lake area and a garden in Floral Court. -

BEAR FAMILY RECORDS TEL +49(0)4748 - 82 16 16 • FAX +49(0)4748 - 82 16 20 • E-MAIL [email protected]

BEAR FAMILY RECORDS TEL +49(0)4748 - 82 16 16 • FAX +49(0)4748 - 82 16 20 • E-MAIL [email protected] ARTIST Eden Ahbez TITLE Wild Boy The Lost Songs Of Eden Ahbez LABEL Bear Family Productions CATALOG # BAF 18018 PRICE-CODE BAF EAN-CODE ÇxDTRBAMy180187z FORMAT VINYL-album with gatefold sleeve • 180g vinyl GENRE Rock 'n' Roll / Tiki TRACKS 14 PLAYING TIME 37:26 G Hippie #1 G 14 rare/unreleased recordings G Guest appearances by Paul Horn, Eartha Kitt, and more G 180 gram vinyl G Fully annotated, with never before seen pictures INFORMATION By now psychedelic music is a mainstay of popular taste. But questions of its origins still linger. As such, BEAR FAMILY RECORDS now submits 'Wild Boy: The Lost Songs Of Eden Ahbez' as fresh evidence in the quest for answers. Over the past twenty years Ahbez has gone from cult figure to harbinger of the Sixties flower-power movement. This notion is born out largely by his 1948 ant- hem of universal love, Nature Boy, and his rare solo album from 1960, titled 'Eden's Island' – one of popular music's earliest con- cept albums. 'Wild Boy: The Lost Songs Of Eden Ahbez' both expands the Ahbez catalog and deepens the notion of a psychedelic movement having roots in the 1950s. Side one acts as a compilation of music that Ahbez wrote in the aftermath of Nature Boy. Inclusion of songs like Palm Springs by the Ray Anthony Orchestra and Hey Jacque by Eartha Kitt give listeners the chance to hear obscure cuts by big-name artists in the context of Ahbez for the first time. -

"A" - You're Adorable (The Alphabet Song) 1948 Buddy Kaye Fred Wise Sidney Lippman 1 Piano Solo | Twelfth 12Th Street Rag 1914 Euday L

Box Title Year Lyricist if known Composer if known Creator3 Notes # "A" - You're Adorable (The Alphabet Song) 1948 Buddy Kaye Fred Wise Sidney Lippman 1 piano solo | Twelfth 12th Street Rag 1914 Euday L. Bowman Street Rag 1 3rd Man Theme, The (The Harry Lime piano solo | The Theme) 1949 Anton Karas Third Man 1 A, E, I, O, U: The Dance Step Language Song 1937 Louis Vecchio 1 Aba Daba Honeymoon, The 1914 Arthur Fields Walter Donovan 1 Abide With Me 1901 John Wiegand 1 Abilene 1963 John D. Loudermilk Lester Brown 1 About a Quarter to Nine 1935 Al Dubin Harry Warren 1 About Face 1948 Sam Lerner Gerald Marks 1 Abraham 1931 Bob MacGimsey 1 Abraham 1942 Irving Berlin 1 Abraham, Martin and John 1968 Dick Holler 1 Absence Makes the Heart Grow Fonder (For Somebody Else) 1929 Lewis Harry Warren Young 1 Absent 1927 John W. Metcalf 1 Acabaste! (Bolero-Son) 1944 Al Stewart Anselmo Sacasas Castro Valencia Jose Pafumy 1 Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive 1944 Johnny Mercer Harold Arlen 1 Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive 1944 Johnny Mercer Harold Arlen 1 Accidents Will Happen 1950 Johnny Burke James Van Huesen 1 According to the Moonlight 1935 Jack Yellen Joseph Meyer Herb Magidson 1 Ace In the Hole, The 1909 James Dempsey George Mitchell 1 Acquaint Now Thyself With Him 1960 Michael Head 1 Acres of Diamonds 1959 Arthur Smith 1 Across the Alley From the Alamo 1947 Joe Greene 1 Across the Blue Aegean Sea 1935 Anna Moody Gena Branscombe 1 Across the Bridge of Dreams 1927 Gus Kahn Joe Burke 1 Across the Wide Missouri (A-Roll A-Roll A-Ree) 1951 Ervin Drake Jimmy Shirl 1 Adele 1913 Paul Herve Jean Briquet Edward Paulton Adolph Philipp 1 Adeste Fideles (Portuguese Hymn) 1901 Jas. -

EDEN Mauro Grossi

EDEN Mauro Grossi Progetto di composizioni originali basate sul brano “Nature Boy” in forma di Tema e Variazioni uscito in cd il 18 ottobre per l'etichetta Abeat. Un lavoro concettuale con trama e motivazioni, coraggioso e poetico in grado di approfondire le innumerevoli implicazioni strutturali di questa fenomenale canzone dovuta ad un autore sorprendente e influente come Eden Ahbez. Il progetto Eden propone un nuovo e creativo approccio agli standard, lontano da qualunque tipo di revival e si configura anche come uno dei più lunghi atti musicali d'amore di cui si abbia notizia: l'amore di Mauro Grossi per un brano che celebra l'amore, intendendo "tolleranza e rispetto", come valori primari. Per questo motivo ogni brano presentato, appartenendo ad uno stile diverso, da un suo apporto specifico, ma trae senso e vantaggi dall'accostamento agli altri. Infatti, benchè tutti originali, i brani hanno un'unica radice, della quale sono variazioni sempre più evolute ed emancipate. Proprio come esseri umani. (continua) Mauro Grossi piano, celesta, arrangiamenti, direzione Claudia Tellini voce Nico Gori clarinetto, clarinetto basso, sax soprano Andrea Dulbecco vibrafono Ares Tavolazzi contrabbasso Walter Paoli batteria, percussioni Possibilità di avere la sezione d'archi in concerto. Estratti dalle prime recensioni pubblicate. “ Bizzarro: un album interamente dedicato alla celebrazione di un unico brano. E' un segno dello straordinario amore da parte del suo ideatore, il pianista Mauro Grossi per una delle composizioni più belle mai scritte non solo in ambito Jazz “Nature Boy”.... Grossi ha elaborato/composto una fantastica serie di variazioni basate sulla melodia di questo meraviglioso pezzo e quindi è possibile ascoltare “Nature Boy” nei contesti più disparati... -

A Bewitching Realm Reopens Tahquitz Canyon Had Been

TAahBqeuwitzitCchaninyognRHeaadlBmeeRn eShoapnegrni-s La to Hippies, Hermits and Evil Spirits. For Decades Its Dangers Made It Off-Limits. Now the ‘NoTrespassing’ Signs Are Coming Down. Los Angeles Times Magazine, Jan 14, 2001 By Ann Japenga SEVERAL YEARS AGO, I WAS LUGGING BOXES into my new Palm Springs home and needed a break from unpacking. Parking my car not far from the spritzing misters downtown, I walked up the flood-control channel toward a massive gash, a door into the mountains: Tahquitz Canyon. Coming toward me down the trail was a lone man. At first I was happy to encounter another hiker, but as he got closer, I picked up an unmistakable scent of evil. He glared at me sideways out of psychotic blue eyes, spraying sweat and spitting out a malicious incantation. A few months later I saw a mug shot of the same fellow in the paper and read that he’d tried to push a group of hikers off a precipice into the canyon. I felt lucky to have survived the man’s wrath, of course, but more than that I felt privileged, as a newcomer, to have met the wrathful spirit of Tahquitz. It was like attending the ultimate insider bash your first week in town. I’d known—in some vague, folkloric way—about the curse of Tahquitz my whole life. Growing up in the San Gabriel Valley, I simply assimilated the notion that there was an awesome canyon out in Palm Springs and weird things happened there. California kids know this. “ere are a thousand stories up there,” affirms helicopter pilot Steve de Jesus, who has assisted in many Tahquitz rescues. -

Prologue Géraldine Gourbe

5 In the Canyon, Revise the Canon Prologue Géraldine Gourbe Revise the Canon The Duty to Remember is Not Sovereign Linda Nochlin has taught me that while a wish to bring certain moments of collective amnesia to general knowledge might admittedly be justifiable, it can paradoxically prove to be counterproductive. Shedding light upon certain veiled practices cannot be envisaged without a critical analysis that can and must acutely consider its own territory. In “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” the author takes a distance from the actions of overexposure and legitimation of veiled knowledge undertaken by her own sisters, who at the time belonged to the Women Art Coalition and the Women’s Art in Revolution groups, the first artist protest groups stemming from the Women’s Liberation Movement. It is therein that lies, in my opinion, her literally revolutionary contribution. From this strategic and discursive deviation, Nochlin names and describes a chain of correlative actions between the emancipation movements that were rapidly expanding in the end of the 1960s on the one hand, and the process of calling into question the Humanities’ epistemological principles on the other. What the North American intellectual saw in these marches and protests was not a blind spot; she rather discerned a disjunctive force, also called, 1 in Michel de Certeau’s words, a founding rupture. This founding rupture is driven by expressions of singularity rubbing and grating against enunciations marked by universality; from then on liberating “questions that were unheard and whose answers were unspoken, that remained to be sought in [...] a labor of 2 common elucidation.” 1. -

Jazz & Tonic Pacific Standard Time

SPECIAL THANKS TO OUR 2012-2013 DONORS Founders Circle ($10,000 and above) Friends ($100 - $499) Regena Cole and the Bob Cole Foundation Biola University Music at Noon The Ella Fitzgerald Charitable Foundation Margot Coleman Stuart Hubbard & Carol Mac Gregor Season Sponsors ($5,000 - $9,999) Lavonne McQuilkin CSULB Alumni Association Mr. & Mrs. Donald Seidler David Wuertele & Tomoko Shimaya Director’s Circle ($1,000 - $4,999) Mr. & Mrs. Charlie Tickner MiraCosta College / Oceanside Vocal Jazz Festival Supporters ($20 - $99) Mike & Erin Mugnai (in kind donation) Louise Reed Mr. & Mrs. Robert Swoish Karin Reilly Patrons ($500 - $999) PACIFIC St. Gregory’s Episcopal Church of Long Beach PERSONNEL STANDARD TIME JAZZ & TONIC PACIFIC STANDARD TIME CHRISTINE GUTER, DIRECTOR Glynis Davies, Director Christine Guter, Director Bradley Allen Marcus Carline Steven Amie Glynis Davies * Emily Jackson ^ Jonathan Eastly Arend Jessurun Ashlyn Grover * Alyssa Keyne Joe Sanders Katrina Kochevar Maria Schafer Jake Lewis Miko Shudo JAZZ & TONIC Christine Li Scott Leeav Sofer ^ + Molly McBride Rachel St. Marseille ^ * Patricia Muresan Jenny Swoish Emilio Tello ^ Jake Tickner Jordan Tickner Riley Wilson GLYNIS DAVIES, DIRECTOR Piano – Anthony Escoto Piano – Kyle Schafer Bass – Daniel Reasoner ^ Bass – Chelsea Stevens Drums – Tyler Kreutel Drums – Brett Kramer ^ FRIDAY, APRIL 19, 2013 ^ Section Leader * Ella Fitzgerald Scholar + Cole Scholar 8:00PM For ticket information please call 562.985.7000 or visit the web at: UNIVERSITY THEATRE PLEASE SILENCE ALL ELECTRONIC MOBILE DEVICES. This concert is funded in part by the INSTRUCTIONALLY RELATED ACTIVITIES FUNDS (IRA) provided by California State University, Long Beach. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To build a strong program at the Bob Cole Conservatory, we must attract the PROGRAM finest young jazz talent. -

February 9-19, 2021

SAVANNAH'S WEEK LONG CELEBRATION OF SONG FEBRUARY 9-19, 2021 AMERICANTRADITIONSCOMPETITION.COM All events will begin at 7pm on the date listed, and remain available to watch at the audience’s leisure until February 28, 2021. TUESDAY FEB. 9 Quarterfinal 1 Sponsored by Tricia & David Guggenheim WEDNESDAY FEB. 10 Quarterfinal 2 Sponsored by Kathie & Les Anderson THURSDAY FEB. 11 Quarterfinal 3 pro Sponsored by Nancy McGirr & David Goslin FRIDAY FEB. 12 Quarterfinal 4 Sponsored by Patty & Heyward Gignilliat TUESDAY FEB. 16 Judges Concert Sponsored by The Charles C. Taylor and Samir gram Nikocevic Charitable Foundation WEDNESDAY FEB. 17 Semifinal 1 Sponsored by Hedy & Michael Fawcett THURSDAY FEB. 18 Semifinal 2 flow Sponsored by Danny Cohen FRIDAY FEB. 19 Final Round Sponsored by Savannah Morning News 14 ATC PRESIDENT 15 ATC DIRECTOR 16 ABOUT THE ATC ATC BOARD OF DIRECTORS EDUCATIONAL OUTREACH 17 JUNIOR ATC 18 IN-KIND DONATIONS of 19 VOLUNTEERS table 20 ATC DONORS 22 AWARDS 24 PAST GOLD MEDAL WINNERS 25 SPONSORS 26 2021 JUDGES cont 28 PIANISTS 29 INSTRUMENTALISTS 30 2021 CONTESTANTS ents W E C R E A T E D Y N A M I C V I D E O C O N T E N T F O R B U S I N E S S A N D C R E A T I V E P L A T F O R M S . S A V A N N A H , G A 3 1 4 0 1 | 7 0 6 . 4 4 9 . 1 2 1 2 WELCOME TO THE 28TH YEAR OF ATC A N O T E F R O M A T C B O A R D P R E S I D E N T Greetings all. -

Download Download

Author: Carter, Dale; Title: Surf Aces Resurfaced: The Beach Boys and the Greening of the American Counterculture, 1963-1973 Surf Aces Resurfaced: The Beach Boys and the Greening of the American Counterculture, 1963-1973 Dale Carter Aarhus University Abstract The rise of the American counterculture between the early- to mid-1960s and early- to mid-1970s was closely associated with the growth of environmentalism. This article explores how both informed popular music, which during these years became not only a prominent form of entertainment but also a forum for cultural and social criticism. In particular, through contextual and lyrical analyses of recordings by The Beach Boys, the article identifies patterns of change and continuity in the articulation of countercultural, ecological, and related sensibilities. During late 1966 and early 1967, the group’s leader Brian Wilson and lyricist Van Dyke Parks collaborated on a collection of songs embodying such progressive thinking, even though the music of The Beach Boys had previously shown no such ambitions. In the short term, their efforts floundered as the risk- averse logic of the commercial music industry prompted group members to resist perceived threats to their established profile. Yet in the long term (and ironically in the name of commercial survival), The Beach Boys began selectively to adopt innovations they had previously shunned. Shorn of its more controversial associations, what had formerly been considered high risk had by 1970 become good business as once-marginal environmentalism gained broader acceptability: thus did ‘America’s band’ articulate the flowering, greening, and fading of the counterculture. Keywords: popular music, ecology, counterculture, Beach Boys Resumen Vol 4, No 1 El auge de la contracultura americana entre principios y mediados de las décadas de 1960 y 1970 guarda una estrecha relación con la expansión del movimiento ecologista. -

Picture As Pdf

1 Cultural Daily Independent Voices, New Perspectives A Taste of Gypsy Boots R. Daniel Foster · Wednesday, January 6th, 2021 If you’ve lived in Los Angeles long enough, you’ll rememberGypsy Boots — a zany health and fitness pioneer who slept in fields, caves and trees and appeared on national TV swinging from a vine and banging a drum. Born Robert Bootzin in San Francisco in 1915, the irrepressible long-haired and often bare-chested Boots had a singular message of spreading “health and happiness.” A long-time L.A. resident, Boots died in 2004 at age 89 – a booster of L.A. Dodgers, Lakers, USC Trojans football and Raiders games right up to the end (clanging his signature cowbell on the sidelines as he chanted, “Don’t panic, go organic!”) Cultural Daily - 1 / 8 - 13.08.2021 2 Gypsy Boots / courtesy of Dan Bootzin Yes, gypsies can reincarnate — at least this jovial one has Now, Boots is back — reincarnated in a way, via a signature health food box of treats: Gypsy Boots Bites. The 12-pack includes mocha, cashew and coconut, peanut butter and chocolate as well as nuts and fruits varieties ($28). The product is an homage to Boots, developed by his son Dan Bootzin, wife Beth and son Timur — a family project that’s been in development for years. Cultural Daily - 2 / 8 - 13.08.2021 3 Presented in a hippy-trippy box printed with swirled flowers, the all-organic snacks can be ordered in an “all flavors” box or as boxes of a single treat. Beth’s niece, Zoe Crouch, masters the Gypsy Boots Bites Instagram account and another niece, Rui Wheaton, creates marketing artwork. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Death in Eden by Habu Eden Ahbez

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Death in Eden by Habu Eden Ahbez. One of the genuinely strange characters of pre-rock American popular music, Eden Ahbez's main claim to fame was as the composer of "Nature Boy." The melodically and lyrically beguiling song was a huge… Read Full Biography. Overview ↓ Biography ↓ Discography ↓ Songs ↓ Credits ↓ Related ↓ facebook twitter tumblr. Artist Biography by Richie Unterberger. One of the genuinely strange characters of pre-rock American popular music, Eden Ahbez's main claim to fame was as the composer of "Nature Boy." The melodically and lyrically beguiling song was a huge pop hit for Nat King Cole; it would be covered by many other reputable performers, including Frank Sinatra, John Coltrane, Sarah Vaughan, and the Great Society (Grace Slick's pre-Jefferson Airplane band). But Ahbez's modern stature rests on a 1960 album that mixed exotica album and beatnik poetry. It rates as one of the goofiest efforts in the goofy exotica genre -- and brother, that's saying something, given the stiff competition. Ahbez boasted a resumé as colorful and mysterious as his music. Born Alexander Aberle in Brooklyn in the early 20th century, he changed his name in the 1940s shortly after moving to (where else?) California. A hippie a good 20 years before his time, he cultivated a Christ-like appearance with his shoulder-length hair and beard. He claimed to live on three dollars a week, sleeping outdoors with his family, eating vegetables, fruits, and nuts. Ahbez's big success was getting Nat King Cole to record "Nature Boy," after diligently pestering some of Cole's associates at the Million Dollar Theater in Los Angeles, where Cole was performing. -

An Interview with Gordon Kennedy)

Considering the Source (An Interview with Gordon Kennedy) Posted on April 9, 2012 by bcxists When “Nature Boy” hit #1 on the Billboard charts in May 1948, post-war Americans viewed its composer, eden ahbez, as both a prophet of hope and a novel curiosity. His image of choice (long hair, beard and sandals) stood in opposition to that of the average red-blooded American male of the period. Yet as this interview with author Gordon Kennedy reveals, there was strong precedence for the alternative values that ahbez introduced to popular music 20 years before they dominated youth culture of the late 1960s. Kennedy is the author of Children of the Sun, a book that chronicles the emergence of primitivism, naturopathic medicine and eco consciousness as it traveled from 19th Century Germany to the West Coast of the United States between WWI and WWII. I had a chance recently to interview Mr. Kennedy about those years leading up to free love and flower-power. -Brian Chidester, 4/8/2012 The cover of Gordon Kennedy’s “Children of the Sun” (1998). Brian Chidester: You’ve spent a lot of time considering the roots of the hippie movement, for lack of a better term. Tell me how you think eden ahbez fits into this. Gordon Kennedy: Well, eden ahbez is one of the most important individuals simply because his hit song “Nature Boy” made him famous, which brought so much media attention to him that we have a lot of photos, news articles and personal encounters from others who met and knew him.