Merivoo-Parro Doktoo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Armas Lihula Valla Rahvas! Lihula on Tänasel Päeval Väheneva Välistama Dubleerivad Ametikohad Elanike Arvuga Vald, Viimase Ja Ebamõistlikud Kulutused

nr 1 (94) / veebruar 2014 1 Lihula valla ajaleht nr 1 (94) / veebruar 2014 Armas Lihula valla rahvas! Lihula on tänasel päeval väheneva välistama dubleerivad ametikohad elanike arvuga vald, viimase ja ebamõistlikud kulutused. 10 aasta jooksul on rahvaarv langenud 14,8%. Vähenev maksu- Sageli kompenseerib rahalise kitsi- maksjate hulk kahandab ka kuse inimeste soov ise panustada valla sissetulekuid – meie ühine ja igapäevaelus aktiivselt kaasa rahakott on väiksem. Võrreldes lüüa. 2013. aastaga on valla eelarve vähenenud ja 2014. aastal peame Näiteks Lihulas esile kerkinud hakkama saama oma jõududega, turvalisuse probleemi lahen- sest valla laenukoormus on suur damiseks kutsusime 3. veebruaril ja uusi laene arendusteks võtta ei vallamajas kokku turvalisuse saa. Soov säilitada olemasolevat ümarlaua, millel osalesid polit- haridusasutuste võrgustikku seinikud, Kaitseliidu esindaja, nõuab aastas vallapoolset lisaraha Lihula vallavolikogu ja vallavalit- VarjeLihula vallavanem Ojala-Toos suurusjärgus 30000€. Tõusnud on suse esindajad ning kooli miinimumpalk, elektrienergia ja õpilasesinduse eestvedaja. soojuse hinnad. Koos arutasime läbi suuremad Meie riigil on sünnipäev, täitub turvalisust puudutavad valu- juba 96. aasta. Riik olemegi meie Tõstatub oluline küsimus – punktid Lihulas ja panime kok- ise - kõik koos, oma tegemiste kuidas minna edasi? Kui raha on ku tegevuskava. Ümarlaual väl- ja toimetamistega. Palju õnne vähem, on vaja teha mõistlikke ja jakäidud ideede tulemusena meile kõigile! vajalikke valikuid ja võtta vastu korraldame 15. märtsil kell 12.00 ka raskeid otsuseid. Peame oma Lihula Kultuurimaja ruumides Elame vabal maal, kus meil on vallas tagama eluks vajamineva Turvalisuse päeva, kus politsei ja õigused ja kohustused. Me peame – hariduse, arstiabi, läbitavad MTÜ Eesti Naabrivalve esindajad tegema otsuseid ja valikuid, et elu teed, turvalisuse. Kõigil lastel tutvustavad kõigile, kuidas koos edendada. -

Lihula Valla Terviseprofiil

Lisa 1 Kinnitatud Lihula Vallavolikogu 28.10.2010 määrusega nr 24 Lihula valla terviseprofiil 2010 1 Sisukord Sisukord 1. Üldandmed ...................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1. Lihula valla asend, pindala, haldusjaotus .......................................................................... 3 1.2. Rahvastik ........................................................................................................................... 3 1.3. Lihula valla loomulik iive .................................................................................................. 7 1.4. Lihula valla eelarve ............................................................................................................ 7 2. Sotsiaalne sidusus ja võrdsed võimalused ...................................................................................... 9 2.1. Tööturu olukord ja toimetulek ........................................................................................... 9 2.2. Tööpuudus, igapäevane tööalane ränne ............................................................................. 9 2.3. Sotsiaalhoolekanne ......................................................................................................... 10 2.4. Sotsiaalselt vähevõimekate suur arv ................................................................................ 12 3. Kogukonna tegevused ja kaasamine ............................................................................................ -

Perioodi 2007–2013 Struktuurivahendite Mõju Regionaalarengule Praxis Ja Centar

Perioodi 2007–2013 struktuurivahendite mõju regionaalarengule Praxis ja Centar Perioodi 2007–2013 struktuurivahendite mõju regionaalarengule Lõpparuanne 2015 Perioodi 2007–2013 struktuurivahendite mõju regionaalarengule Praxis ja Centar Uuringu tellis Rahandusministeerium. Uuring on valminud Euroopa Liidu struktuurivahendite toel. Poliitikauuringute Keskus Praxis on Eesti esimene sõltumatu, mittetulunduslik mõttekeskus, mille eesmärk on toetada analüüsile, uuringutele ja osalusdemokraatia põhimõtetele rajatud poliitika kujundamise protsessi. Rakendusuuringute Keskus CentAR on sõltumatu eraalgatuslik uuringu- ja konsultatsiooniettevõte, mis keskendub rakenduslike analüüsi- ja uuringuprojektide teostamisele nii era- kui avalikus sektoris. Poliitikauuringute Keskus Praxis Rakendusuuringute Keskus CentAR Tornimäe 5, III korrus Nunne 5-3 10145 Tallinn 10133 Tallinn tel 640 8000 tel 6173306 www.praxis.eeVäljaandes sisalduva teabe kasutamisel www.palumecentar viidata.ee allikale: Perioodi 2007–2013 struktuurivahendite mõju regionaalarengule. Tallinn: Poliitikauuringute Keskus Praxis ja [email protected] [email protected] Rakendusuuringute Keskus CentAR. 2015 1. 2. ISBN 3. Poliitikauuringute Keskus Praxis 4. Tornimäe 5, III korrus 5. 10145 Tallinn Perioodi 2007–2013 struktuurivahendite mõju regionaalarengule Praxis ja Centar Autorid: Katrin Pihor on Praxise juhatuse liige ja majanduspoliitika programmijuht. Roll projektis: projektijuht, kvalitatiivse analüüsi töörühma juht. Mari Rell on Praxis majanduspoliitika programmi analüütik. Roll projektis: -

Tiitelleht Ja Sisukord

Tartu Ülikool Loodus- ja tehnoloogiateaduskond Ökoloogia ja Maateaduste instituut Geograafia osakond Lõputöö Matsalu lahe lõunakalda puisrohumaade pindala muutused II maailmasõja järgsel perioodil Mikk-Erik Saidla Juhendaja: PhD Anneli Palo Kaitsmisele lubatud: Juhendaja: Osakonna juhataja: Tartu 2013 Sisukord Sissejuhatus ................................................................................................................................ 3 1. Puisrohumaad ......................................................................................................................... 4 1.1. Puisniidu mõiste .............................................................................................................. 4 1.2. Puiskarjamaa mõiste ........................................................................................................ 4 1.3. Puisrohumaade tähtsus looduskaitses ja hooldamine ...................................................... 5 1.4. Matsalu lahe lõunakalda puisrohumaad .......................................................................... 8 2. Materjal ja metoodika ........................................................................................................... 11 2.1. Uurimisala ..................................................................................................................... 11 2.2. Töö Maa-ameti arhiivis ................................................................................................. 11 3. Tulemused ........................................................................................................................... -

Seletuskirja Ettepanek

LIHULA VALLA ÜLDPLANEERING SISUKORD 1 . ÜLDOSA.............................................................................................................................................5 1.1 . ASUKOHT JA KUJUNEMINE..............................................................................................5 1.2 . LOODUSKESKKOND...........................................................................................................6 1.3 . RAHVASTIK JA ASUSTUS..................................................................................................7 1.3.1 . Rahvaarvu muutumine...........................................................................7 1.3.2 . Asustus ja asulate omavahelised suhted.................................................8 2 . LIHULA VALLA VISIOON 2015.................................................................................................10 3 . ARENGUSTRATEEGIA PÕHISUUNAD AASTANI 2015........................................................11 3.1 . SOTSIAALNE INFRASTRUKTUUR..................................................................................11 3.1.1 . Haridus................................................................................................12 3.1.2 . Kultuur................................................................................................13 3.1.3 . Kogudused ja kalmistud.......................................................................14 3.1.4 . Sotsiaalhooldus, tervishoid..................................................................14 3.1.5 . -

Rahvastiku Ühtlusarvutatud Sündmus- Ja Loendusstatistika

EESTI RAHVASTIKUSTATISTIKA POPULATION STATISTICS OF ESTONIA __________________________________________ RAHVASTIKU ÜHTLUSARVUTATUD SÜNDMUS- JA LOENDUSSTATISTIKA REVIEWED POPULATION VITAL AND CENSUS STATISTICS Hiiumaa 1965-1990 Läänemaa 1965-1990 Kalev Katus Allan Puur Asta Põldma Nõv a Pürksi Risti KÄRDLA Linnamäe Vormsi Taebla Lauka Pühalepa HAAPSALU Käina Ridala Martna Kullamaa Emmaste Lihula Lihula Hanila Tallinn 2002 EESTI KÕRGKOOLIDEVAHELINE DEMOUURINGUTE KESKUS ESTONIAN INTERUNIVERSITY POPULATION RESEARCH CENTRE RAHVASTIKU ÜHTLUSARVUTATUD SÜNDMUS- JA LOENDUSSTATISTIKA REVIEWED POPULATION VITAL AND CENSUS STATISTICS Hiiumaa 1965-1990 Läänemaa 1965-1990 Kalev Katus Allan Puur Asta Põldma RU Sari C Nr 21 Tallinn 2002 © Eesti Kõrgkoolidevaheline Demouuringute Keskus Estonian Interuniversity Population Research Centre Kogumikuga on kaasas diskett Hiiumaa ja Läänemaa rahvastikuarengut kajastavate joonisfailidega, © Eesti Kõrgkoolidevaheline Demouuringute Keskus. The issue is accompanied by the diskette with charts on demographic development of Hiiumaa and Läänemaa population, © Estonian Interuniversity Population Research Centre. ISBN 9985-820-70-3 EESTI KÕRGKOOLIDEVAHELINE DEMOUURINGUTE KESKUS ESTONIAN INTERUNIVERSITY POPULATION RESEARCH CENTRE Postkast 3012, Tallinn 10504, Eesti Kogumikus esitatud arvandmeid on võimalik tellida ka elektroonilisel kujul Lotus- või ASCII- formaadis. Soovijail palun pöörduda Eesti Kõrgkoolidevahelise Demouuringute Keskuse poole. Tables presented in the issue on diskettes in Lotus or ASCII format could be -

Changes in the Classification of Estonian Administrative Units and Settlements (EHAK)

Changes in the classification of Estonian administrative units and settlements (EHAK) Following the implementation of the latest changes, the number of administrative units and settlements in the Republic of Estonia is as follows: Counties 15 Administrative units with a government 213 of which: rural municipalities 183 cities 30 Settlements 4 699 of which: cities 30 cities without municipal status 17 towns 12 small towns 188 villages 4 452 Changes as of 23 Sept 2016: Pursuant to Regulation No. 38 of the Minister of Public Administration ((RT I, 20.09.2016, 1 ), the following changes are made: In Valga country: In Otepää rural municipality changed the division line between Otepää city and Otepää , Kasolatsi , Pühajärve and Nüpli villages. Following changes are made: Otepää city (old code 5754, new code 5755 ), Otepää village (old code 5753, new code 5752 ), Nüpli village (old code 5566, new code 5567 ), Pühajärve village (old code 6658, new code 6659 ). Kasolatsi village code (2837) is not changed. The classification characteristics are 82 636 8. Changes as of 14 Sept 2015: Pursuant to Regulation No. 31 of the Minister of Public Administration ((RT I, 11.09.2015, 1 ), the following changes are made: In Järva county: In Imavere rural municipality, Hermani village (code 185 ) is reinstated. Käsukonna village (old code 3936) is assigned the new code 3937 . The classification characteristics are 51 234 8. In Pärnu county: In Tahkuranna rural municipality, Mereküla village (code 4874 ) is reinstated. Reiu village (old code 6924 ) is assigned the new code 6925 . The classification characteristics are 67 848 8. Changes as of 12 Dec 2014: Pursuant to Regulation No. -

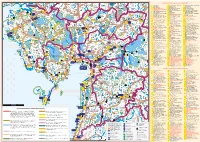

Pärnumaa-Kaart-EST-FIN.Pdf

gi jõ E Kirna E 5 E äru Kiideva Raana jõgi Kilgi K jõgi jõgi VAATAMISVÄÄRSUSED PÄRNU MAAKONNAS Puise km T 4 a ra Kabeli 2 m Järvakandi ti Kastja Päärdu l Velisemõisa Nurtu Rõud s l k e jõgi i i Kõrbja n R Vana-Vigala Velise- Inda 9 Mäda Illaste raba n Nõlva 2 Nõlvassoo Saarepõllu Võeva Nurtu-Nõlva Soo-otsa Karjaküla 1 Auto24ring 44 Kirsi Vanasõidukite muuseum 91 Soomaa rahvuspark, looduskeskus 8 Nõlva a Suurrahu Läti l 1 Rõude Laiküla E Tõrasoo p k 2 Villa Andropoff 45 Laelatu puisniit ja matkarajad a Eidapere m lka Kenni R Selja Kasa m Allikotsa Aravere Mäliste k 3 White Beach Golf 46 Hanila muuseum 92 Tipu Looduskool 57 Oese Kohtru 0 Matsalu laht 56 Paljasmaa 1 ri i Matsalu rahvuspark Araste jõgi Saug Kullimaa r 4 Valgeranna Seikluspark 47 Hanila Pauluse kirik (13. saj) 93 Kõpu Külastuskeskus jõgi Eidapere ü Kasari jõgi jõgi Vängla õgi T 52 Seli Vigala- Nurtu j a ra Valgeranna liivarand, promenaad Kõmsi tarandkalmed Piesta Kuusikaru talu Kurevere u 5 48 94 Kelu Rannu Vigala jõgi Keemu Keskküla jõgi Tõnumaa Vanamõisa Palase Nurme Ojaäärse Rahkama Penijõgi Kloostri Manni Mukri Pärn ja vaatlustorn 49 Karuse Püha Margareeta kirik 95 Vändra Martini luteri kirik (1787) 59 Kojastu Vaguja Reonda Vänd 2 Uluste Jõeääre Rääski Kõnn Ð 6 Audru mõisakompleks (18. saj) ja (13. saj) 96 Vändra Peeter-Pauli apostliku- ü 58 60 u jõgi 5 Saastna 51 Matsalu Kasari Kõnnu Mukri mka Liustemäe 29 Pagasi Mõisimaa Rumba Konnapere Audru muuseum 50 Ranna Rantšo õigeusu kirik (1868) jõgi Penijõe Ojapere Rukkiküla Kaisma raba 7 Ellamaa Kesu 2 u DC Audru Püha Risti -

Lihula Piirkond

Lihula piirkond Endise Lihula valla alal (v.a. Lihula linn) paiknevad kinnistud, millistel asuvad ehitised on kantud ehitisregistrisse osaliselt või on ehitiste andmed puudulikud. Ehitise aadressi juures on märgitud probleemsete ehitiste arv. Alaküla Alaküla küla-1, Kure-2, Kõllamaa-1, Madise-1, Mardi-1, Mihkli-Ado-1, Pärna-3, Taru-1, Uue-Taatsi-4, Uusmaa-1 Rootsi-Aruküla Aaviku-1, Oja-1, Sepa-3, Tõnise-1 Hälvati küla Hälvati küla-1, Jaagu-3, Kaasiku-4, Korju-Aadu-1, Kuivati-2, Mäe-1, Mäealuse-2, Põlluvahi-1, Sepa-1, Tammealuse-2, Vana-Saare-1 Jõeääre küla Annimõisa-5 Järise küla Korju-2, Matsi-1, Nurme-vallasvara, Poe-1, Sepa-1 Keemu küla Lili-3, Kajaka-1, Kaluri-1, Laine-3, Paadi-1, Tormi-2, Võrgu-1 Kelu küla Asupi-1, Järve-1, Jüri-Jaagu-5, Laari-1, Madis-Mardi-5, Pärtli-Jaani-2, Sepa-Jaani-2, Talviku-3, Väädiko-3 Kirbla küla Kirbla küla-2, Altkruusi-1, Andruse-1, Hansu-Jaani-1, Jaanikse-1, Jaanimäe-2, Kase-1, Kassi-1, Koguduse-1, Kuldre-1, Kupja-1, Nurga-4, Peetri-1, Pärna-1, Põldotsa-3, Saare-1, Selja-3, Siilimäe-1, Soome-1, Tõnise-1 Kirikuküla Kirikuküla-7, Ennu-2, Hendriku-4, Kaasiku-1, Kirikuküla laut-1, Lusti-2, Pajumaa-2, Tika-1, Tikavälja-18, Tohvri-14, Tooma-1, Väljasepa-1 Kloostri küla Kloostri küla-1, Kalda-1, Kase-1, Kuusiku-1, Mulinroosi-1, Mäe-1, Nurme-1, Pärna-5, Põhja-1, Rehe-1, Rehemäe-2 Kunila küla Metsavahi-1 Laulepa küla Aaviku-1, Ansi-6, Lehise-1 Lautna küla Aadu-1, Liivamäe-1, Pangasauna-1, Vahtra-2 Liustemäe küla Liustemäe-5, Vellamo-5 Matsalu küla Jääkeldri-2, Kasevälja-2, Lotmani-3, Metsamäe-9, Mõisaveere-2, -

Abiks Loodusevaatlejale 100 Saksa-Eesti Kohanimed

EESTI TEADUSTE AKADEEMIA EESTI LOODUSEUURIJATE SELTS Saksa-Eesti Kohanimed Abiks loodusevaatlejale nr 100 Tartu 2016 Eesti Looduseuurijate Seltsi väljaanne Küljendus: Raino Suurna Toimetaja: Rein Laiverik Kaanepilt on 1905. a hävinud Järvakandi mõisahoonest (Valdo Prausti erakogu), Linda Kongo foto (Rein Laiveriku erakogu). ISSN 1406-278X ISBN 978-9949-9613-6-8 © Eesti Looduseuurijate Selts Linda Kongo 3 Sisukord 1. Autori eessõna .............................................................................................................................................................................. 5 2. Sada tarka juhendit looduse vaatlemiseks ................................................................................................................................... 6 3. Lühenditest ................................................................................................................................................................................... 9 4. Kohanimed ................................................................................................................................................................................. 10 5. Allikmaterjalid .......................................................................................................................................................................... 301 4 Eessõna Käesolevas väljaandes on tabeli kujul esitatud saksakeelse tähestiku alusel koos eestikeelse vastega kohanimed, mis olid kasutusel 18. ja 19. sajandil – linnad, külad, asulad -

Lääne County

Lihula valla ühisveevärgi ja –kanalisatsiooni arendamise kava 2012-2024 SISUKORD 1 SISSEJUHATUS ............................................................................................. 5 2 ÜLEVAADE ÜHISVEEVARUSTUST JA –KANALISATSIOONI KÄSITLEVATEST ALUSDOKUMENTIDEST ......................................................... 7 2.1 ÜLDIST ..................................................................................................................... 7 2.2 ÜLEVAADE ÜVK-d PUUDUTAVATEST ÕIGUSAKTIDEST JA DIREKTIIVIDEST .............................................................................................................. 7 2.3 ÜLEVAADE LÄHTEANDMETEST JA ALUSDOKUMENTIDEST ............... 9 2.3.1 Lääne-Eesti vesikonna veemajanduskava .............................................................. 9 2.3.2 Matsalu alamvesikonna veemajanduskava ............................................................ 9 2.3.3 Lihula valla üldplaneering ..................................................................................... 9 2.3.4 Lihula valla arengukava ....................................................................................... 10 2.3.5 Vee erikasutusluba ............................................................................................... 10 2.3.6 Matsalu valgala piirkonna veeprojekt .................................................................. 11 2.3.7 Kokkuvõte olemasolevatest lähteandmetest ........................................................ 12 3 LIHULA VALLA SOTSIAALMAJANDUSLIK ÜLEVAADE .......................... -

(Asustusüksus) Alevid Alevikud Külad Kehra Aegviidu Aavere Alavere Anija

Riigihalduse ministri 11. oktoobri 2017. a määruse nr 72 „Asustusüksuste nimistu kinnitamine ning nende lahkmejoonte määramine” lisa 1 (riigihalduse ministri 10.10.2019 määruse nr 48 sõnastuses) Asustusüksuste nimistu HARJU MAAKOND ANIJA vald [jõust. 21.10.2017 Anija Vallavolikogu valimistulemuste väljakuulutamise päeval - Anija valla valimiskomisjoni 20.10.2017 otsus nr 7] Linn (asustusüksus) Alevid Alevikud Külad Kehra Aegviidu Aavere Alavere Anija Arava Härmakosu Kaunissaare Kehra Kihmla Kuusemäe Lehtmetsa Lilli Linnakse Looküla Lükati Mustjõe Paasiku Parila Partsaare Pikva Pillapalu Rasivere Raudoja Rooküla Salumetsa Salumäe Soodla Uuearu Vetla Vikipalu Voose Ülejõe HARKU vald [jõust. 21.10.2017 Harku Vallavolikogu valimistulemuste väljakuulutamise päeval - Harku valla valimiskomisjoni 20.10.2017 otsus nr 12] Linn (asustusüksus) Alevid Alevikud Külad Harku Adra Tabasalu Harkujärve Humala Ilmandu Kumna Kütke Laabi Liikva Meriküla Muraste Naage Rannamõisa Suurupi Sõrve Tiskre Tutermaa Türisalu Vahi Vaila Viti Vääna Vääna-Jõesuu JÕELÄHTME vald [jõust. 21.10.2017 Jõelähtme Vallavolikogu valimistulemuste väljakuulutamise päeval - Jõelähtme valla valimiskomisjoni 20.10.2017 otsus nr 9] Linn (asustusüksus) Alevid Alevikud Külad Kostivere Aruaru Loo Haapse Haljava Ihasalu Iru Jõelähtme Jõesuu Jägala Jägala-Joa Kaberneeme Kallavere Koila Koipsi Koogi Kostiranna Kullamäe Liivamäe Loo Maardu Manniva Neeme Nehatu Parasmäe Rammu Rebala Rohusi Ruu Saha Sambu Saviranna Uusküla Vandjala Võerdla Ülgase KEILA linn [jõust. 21.10.2017 Keila Linnavolikogu valimistulemuste väljakuulutamise päeval - Keila linna valimiskomisjoni 20.10.2017 otsus nr 6] Linn (asustusüksus) Alevid Alevikud Külad Keila KIILI vald [jõust. 21.10.2017 Kiili Vallavolikogu valimistulemuste väljakuulutamise päeval - Kiili valla valimiskomisjoni 20.10.2017 otsus nr 10] Linn (asustusüksus) Alevid Alevikud Külad Kiili Kangru Arusta Luige Kurevere Lähtse Metsanurga Mõisaküla Nabala Paekna Piissoo Sausti Sookaera Sõgula Sõmeru Vaela KOSE vald [jõust.