Walking Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sell-1536, Field Trip Notes, , MILS

CONTACT INFORMATION Mining Records Curator Arizona Geological Survey 416 W. Congress St., Suite 100 Tucson, Arizona 85701 520-770-3500 http://www.azgs.az.gov [email protected] The following file is part of the James Doyle Sell Mining Collection ACCESS STATEMENT These digitized collections are accessible for purposes of education and research. We have indicated what we know about copyright and rights of privacy, publicity, or trademark. Due to the nature of archival collections, we are not always able to identify this information. We are eager to hear from any rights owners, so that we may obtain accurate information. Upon request, we will remove material from public view while we address a rights issue. CONSTRAINTS STATEMENT The Arizona Geological Survey does not claim to control all rights for all materials in its collection. These rights include, but are not limited to: copyright, privacy rights, and cultural protection rights. The User hereby assumes all responsibility for obtaining any rights to use the material in excess of “fair use.” The Survey makes no intellectual property claims to the products created by individual authors in the manuscript collections, except when the author deeded those rights to the Survey or when those authors were employed by the State of Arizona and created intellectual products as a function of their official duties. The Survey does maintain property rights to the physical and digital representations of the works. QUALITY STATEMENT The Arizona Geological Survey is not responsible for the accuracy of the records, information, or opinions that may be contained in the files. The Survey collects, catalogs, and archives data on mineral properties regardless of its views of the veracity or accuracy of those data. -

Michael Kenney Paleozoic Stratigraphy of the Grand Canyon

Michael Kenney Paleozoic Stratigraphy of the Grand Canyon The Paleozoic Era spans about 250 Myrs of Earth History from 541 Ma to 254 Ma (Figure 1). Within Grand Canyon National Park, there is a fragmented record of this time, which has undergone little to no deformation. These still relatively flat-lying, stratified layers, have been the focus of over 100 years of geologic studies. Much of what we know today began with the work of famed naturalist and geologist, Edwin Mckee (Beus and Middleton, 2003). His work, in addition to those before and after, have led to a greater understanding of sedimentation processes, fossil preservation, the evolution of life, and the drastic changes to Earth’s climate during the Paleozoic. This paper seeks to summarize, generally, the Paleozoic strata, the environments in which they were deposited, and the sources from which the sediments were derived. Tapeats Sandstone (~525 Ma – 515 Ma) The Tapeats Sandstone is a buff colored, quartz-rich sandstone and conglomerate, deposited unconformably on the Grand Canyon Supergroup and Vishnu metamorphic basement (Middleton and Elliott, 2003). Thickness varies from ~100 m to ~350 m depending on the paleotopography of the basement rocks upon which the sandstone was deposited. The base of the unit contains the highest abundance of conglomerates. Cobbles and pebbles sourced from the underlying basement rocks are common in the basal unit. Grain size and bed thickness thins upwards (Middleton and Elliott, 2003). Common sedimentary structures include planar and trough cross-bedding, which both decrease in thickness up-sequence. Fossils are rare but within the upper part of the sequence, body fossils date to the early Cambrian (Middleton and Elliott, 2003). -

Sedimentological Interpretation of the Tonto Group Stratigraphy (Grand

Lithulogy and Mineral Resources, Vol. J9, No. 5, 2004. pp. 480-484. From Litologiya i Poleznye Iskopaemye, No. 5, 2004, pp. 552-557. Original English Text Copyright © 2004 by Berthault. Sedimentological Interpretation of the Tonto Group 1 Stratigraphy (Grand Canyon Colorado River) G. Berthault 28 boulevard Thiers, 78250 Meulan, France Received October 27, 2003 Abstract—Sedimentological analysis and reconstruction of sedimentation conditions of the Tonto Group (Grand Canyon of Colorado River) reveals that deposits of different stratigraphic sub-divisions were formed simulta- neously in different lithodynamic zones of the Cambrian paleobasin. Thus, the stratigraphic divisions of the geo- logical column founded on the principles of Steno do not correspond to the reality of sedimentary genesis. INTRODUCTION stratotypes can be made by application of the principle In my previous article (Berthault, 2002), I demon- of superposition. For example, the Oxfordian precedes strated on the basis of experiments in sedimentation of the Kimmeridgian. heterogeneous sand mixtures in flow conditions that the Geologists have recognized the existence of marine three principles of superposition, continuity and origi- transgressions and regressions in sedimentary basins. nal horizontality of strata affirmed by N. Steno should They are characterized by discordances between two be reconsidered and supplemented. superposed formations (change in orientation of strati- Because Steno assumed from observation of strati- fication and an erosion surface). Inasmuch as "stages" fied rocks that superposed strata of sedimentary rocks and "series" are defined mostly by paleontological were successive layers of sediment, a stratigraphic composition of the strata (Geologicheskii slovar..., scale was devised as a means of providing a relative 1960), stratigraphic units do not take into account litho- chronology of the Earth's crust. -

GRAND CANYON GUIDE No. 6

GRAND CANYON GUIDE no. 6 ... excerpted from Grand Canyon Explorer … Bob Ribokas AN AMATEUR'S REVIEW OF BACKPACKING TOPICS FOR THE T254 - EXPEDITION TO THE GRAND CANYON - MARCH 2007 Descriptions of Grand Canyon Layers Grand Canyon attracts the attention of the world for many reasons, but perhaps its greatest significance lies in the geologic record that is so beautifully preserved and exposed here. The rocks at Grand Canyon are not inherently unique; similar rocks are found throughout the world. What is unique about the geologic record at Grand Canyon is the great variety of rocks present, the clarity with which they're exposed, and the complex geologic story they tell. Paleozoic Strata: Kaibab depositional environment: Kaibab Limestone - This layer forms the surface of the Kaibab and Coconino Plateaus. It is composed primarily of a sandy limestone with a layer of sandstone below it. In some places sandstone and shale also exists as its upper layer. The color ranges from cream to a greyish-white. When viewed from the rim this layer resembles a bathtub ring and is commonly referred to as the Canyon's bathtub ring. Fossils that can be found in this layer are brachiopods, coral, mollusks, sea lilies, worms and fish teeth. Toroweap depositional environment Toroweap Formation - This layer is composed of pretty much the same material as the Kaibab Limestone above. It is darker in color, ranging from yellow to grey, and contains a similar fossil history. Coconino depositional environment: Coconino Sandstone - This layer is composed of pure quartz sand, which are basically petrified sand dunes. Wedge-shaped cross bedding can be seen where traverse-type dunes have been petrified. -

Grand Canyon

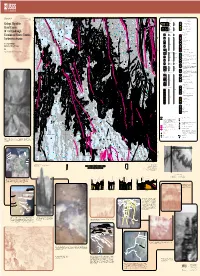

U.S. Department of the Interior Geologic Investigations Series I–2688 14 Version 1.0 4 U.S. Geological Survey 167.5 1 BIG SPRINGS CORRELATION OF MAP UNITS LIST OF MAP UNITS 4 Pt Ph Pamphlet accompanies map .5 Ph SURFICIAL DEPOSITS Pk SURFICIAL DEPOSITS SUPAI MONOCLINE Pk Qr Holocene Qr Colorado River gravel deposits (Holocene) Qsb FAULT CRAZY JUG Pt Qtg Qa Qt Ql Pk Pt Ph MONOCLINE MONOCLINE 18 QUATERNARY Geologic Map of the Pleistocene Qtg Terrace gravel deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Pc Pk Pe 103.5 14 Qa Alluvial deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Pt Pc VOLCANIC ROCKS 45.5 SINYALA Qti Qi TAPEATS FAULT 7 Qhp Qsp Qt Travertine deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Grand Canyon ၧ DE MOTTE FAULT Pc Qtp M u Pt Pleistocene QUATERNARY Pc Qp Pe Qtb Qhb Qsb Ql Landslide deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Qsb 1 Qhp Ph 7 BIG SPRINGS FAULT ′ × ′ 2 VOLCANIC DEPOSITS Dtb Pk PALEOZOIC SEDIMENTARY ROCKS 30 60 Quadrangle, Mr Pc 61 Quaternary basalts (Pleistocene) Unconformity Qsp 49 Pk 6 MUAV FAULT Qhb Pt Lower Tuckup Canyon Basalt (Pleistocene) ၣm TRIASSIC 12 Triassic Qsb Ph Pk Mr Qti Intrusive dikes Coconino and Mohave Counties, Pe 4.5 7 Unconformity 2 3 Pc Qtp Pyroclastic deposits Mr 0.5 1.5 Mၧu EAST KAIBAB MONOCLINE Pk 24.5 Ph 1 222 Qtb Basalt flow Northwestern Arizona FISHTAIL FAULT 1.5 Pt Unconformity Dtb Pc Basalt of Hancock Knolls (Pleistocene) Pe Pe Mၧu Mr Pc Pk Pk Pk NOBLE Pt Qhp Qhb 1 Mၧu Pyroclastic deposits Qhp 5 Pe Pt FAULT Pc Ms 12 Pc 12 10.5 Lower Qhb Basalt flows 1 9 1 0.5 PERMIAN By George H. -

New Hance Trail

National Park Service Grand Canyon U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon National Park Arizona New Hance Trail In 1883, "Captain" John Hance became the first European American to settle at the Grand Canyon. He originally built his trails for mining, but quickly determined the real money lay in work as a guide and hotel manager. From the very start of his tourism business, with his Tennessee drawl, spontaneous wit, uninhibited imagination, and ability to never repeat a tale in exactly the same way, he developed a reputation as an eccentric and highly entertaining storyteller. The scattered presence of abandoned asbestos and copper mines are a reminder of his original intentions for the area. Shortly after his arrival, John improved an old Havasupai trail at the head of today's Hance Creek drainage, the "Old Hance Trail," but it was subject to frequent washouts. When rockslides made it impassable he built the New Hance Trail down Red Canyon. Today's trail very closely follows the trail built in 1894. The New Hance Trail developed a reputation similar to that of the original trail, eliciting the following comment from travel writer Burton Homes in 1904 (he did not exaggerate by much): There may be men who can ride unconcernedly down Hance's Trail, but I confess I am not one of them. My object in descending made it essential that I should live to tell the tale, and therefore, I mustered up sufficient moral courage to dismount and scramble down the steepest and most awful sections of the path on foot …. -

Grand Canyon Supergroup, Northern Arizona

Unconformity at the Cardenas-Nankoweap contact (Precambrian), Grand Canyon Supergroup, northern Arizona DONALD P. ELSTON I U.S. Geological Survey, Flagstaff, Arizona 86001 G. ROBERT SCOTT* ' ABSTRACT sedimentary and volcanic rocks about Group (Noble, 1914) and overlying strata 4,000 m thick overlies crystalline basement of the Chuar Group (Ford and Breed, Red-bed strata of the Nankoweap For- rocks (—1.7 b.y. old; Pasteels and Silver, 1973). Because the Nankoweap had not mation unconformably overlie the 1965). These strata, in turn, are overlain by been subdivided into named formations, —l,100-m.y.-old Cardenas Lavas of the sandstone of Early and Middle Cambrian Maxson (1961) reduced the Nankoweap to Unkar Group in the eastern Grand Canyon. age. Near the middle of the series, a 300- formational rank and renamed it the Nan- An unconformity and an apparent discon- m-thick section of basaltic lava flows is un- koweap Formation, a usage herein adopted formity are present. At most places the conformably overlain by about 100 m of (Art. 9a, 15c, American Commission on upper member of the Nankoweap overlies red-brown and purplish sandstone and Stratigraphic Nomenclature, 1961). The the Cardenas, and locally an angular dis- siltstone. The lavas — named the Cardenas Grand Canyon Series of Walcott (1894) cordance can be recognized that reflects the Lavas or Cardenas Lava Series by Keyes thus consists of three distinct major units; truncation of 60 m of Cardenas. This un- (1938), and adopted as the Cardenas Lavas they are, in ascending order, the Unkar conformity also underlies a newly recog- by Ford and others (1972) — and the over- Group, Nankoweap Formation, and Chuar nized ferruginous sandstone of probable lying red sandstone were included in the Group; this series is here redesignated the local extent that underlies the upper upper part of Walcott's (1894) Precam- Grand Canyon Supergroup, as current member and that herein is called the fer- brian Unkar terrane. -

A Hiker's Companion to GRAND CANYON GEOLOGY

A Hiker’s Companion to GRAND CANYON GEOLOGY With special attention given to The Corridor: North & South Kaibab Trails Bright Angel Trail The geologic history of the Grand Canyon can be approached by breaking it up into three puzzles: 1. How did all those sweet layers get there? 2. How did the area become uplifted over a mile above sea level? 3. How and when was the canyon carved out? That’s how this short guide is organized, into three sections: 1. Laying down the Strata, 2. Uplift, and 3. Carving the Canyon, Followed by a walking geological guide to the 3 most popular hikes in the National Park. I. LAYING DOWN THE STRATA PRE-CAMBRIAN 2000 mya (million years ago), much of the planet’s uppermost layer was thin oceanic crust, and plate tectonics was functioning more or less as it does now. It begins with a Subduction Zone... Vishnu Schist: 1840 mya, the GC region was the site of an active subduction zone, crowned by a long volcanic chain known as the Yavapai Arc (similar to today’s Aleutian Islands). The oceanic crust on the leading edge of Wyomingland, a huge plate driving in from the NW, was subducting under another plate at the zone, a terrane known as the Yavapai Province. Subduction brought Wyomingland closer and closer to the arc for 150 million years, during which genera- tions of volcanoes were born and laid dormant along the arc. Lava and ash of new volcanoes mixed with the eroded sands and mud from older cones, creating a pile of inter-bedded lava, ash, sand, and mud that was 40,000 feet deep! Vishnu Schist Zoroaster Granite Wyomingland reached the subduction zone 1700 mya. -

Deposition of the Tapeats Sandstone (Cambrian) in Central Arizona

Deposition of the Tapeats Sandstone (Cambrian) in central Arizona RICHARD HEREFORD U.S. Geological Survey, 601 East Cedar Avenue, Flagstaff, Arizona 86001 ABSTRACT stratigraphy of the Tapeats Sandstone in Bright Angel Shale and Muav Limestone central Arizona. This area lies along the are absent, and the Tapeats Sandstone is Grain size, bedding thickness, dispersion southern margin of the Colorado Plateau overlain unconformably by the Chino Val- of cross-stratification azimuths, and as- and includes most of the headwaters and ley Formation that was thought to be of semblages of sedimentary structures and northern reaches of the Verde and East probable Cambrian age when defined by trace fossils vary across central Arizona; Verde Rivers (Fig. 1). Hereford (1975). The results of this study they form the basis for recognizing six Relatively thin Cambrian sandstone de- indicate that the Chino Valley Formation facies (A through F) in the Tapeats posits such as the Tapeats are the basal and Tapeats Sandstone are separated by a Sandstone. Five of these (A through E), coarse-grained facies of a transgressive se- major stratigraphic break which probably present in western central Arizona, are quence that extended along north-trending spans several periods. marine deposits containing the trace fossil strandlines throughout the Rocky This study is restricted to data obtainable Corophioides; several intertidal environ- Mountain states (Lochman-Balk, 1971, p. through field observations, such as the ments are represented. The association of 95 — 103). -

Isochron Discordances and the Role of Inheritance and Mixing of Radioisotopes in the Mantle and Crust

Chapter 6 Isochron Discordances and the Role of Inheritance and Mixing of Radioisotopes in the Mantle and Crust Andrew A. Snelling, Ph.D.* Abstract. New radioisotope data were obtained for ten rock units spanning the geologic record from the recent to the early Precambrian, five of these rock units being in the Grand Canyon area. All but one of these rock units were derived from basaltic magmas generated in the mantle. The objective was to test the reliability of the model and isochron “age” dating methods using the K-Ar, Rb-Sr, Sm-Nd, and Pb-Pb radioisotope systems. The isochron “ages” for these rock units consistently indicated that the α-decaying radioisotopes (238U, 235U, and 147Sm) yield older “ages” than the β-decaying radioisotopes (40K, 87Rb). Marked discordances were found among the isochron “ages” yielded by these radioisotope systems, particularly for the seven Precambrian rock units studied. Also, the longer the half-life of the α- or β-decaying radioisotope, and/or the heavier the atomic weight of the parent radioisotope, the greater was the isochron “age” it yielded relative to the other α- or β-decaying radioisotopes respectively. It was concluded that because each of these radioisotope systems was dating the same geologic event for each rock unit, the only way this systematic isochron discordance could be reconciled would be if the decay of the parent radioisotopes had been accelerated at different rates at some time or times in the past, the α-decayers having been accelerated more than the β-decayers. However, a further complication to this pattern is that the radioisotope endowments of the mantle sources of basaltic magmas can sometimes be inherited by the magmas without resetting of the radioisotope * Geology Department, Institute for Creation Research, Santee, California 394 A. -

Younger Precambrian Geology in Southern Arizona

Younger Precambrian Geology in Southern Arizona GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 566 Younger Precambrian Geology in Southern Arizona By ANDREW F. SHRIDE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 566 Stratigraphic^ lithologic^ and structural features of younger Precambrian rocks of southern Arizona as a basis for understanding their paleogeography and establishing their correlation UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1967 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY William T. Pecora, Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. OS 67-238 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price 65 cents (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Page Abstract.__________________________________________ 1 Apache Group Continued Introduction. ______________________________________ 2 Basalt flows.___________________________________ 42 Older Precambrian basement----_----___--___________ 4 General features and distribution.____________ 42 Pre-Apache unconformity._----_-_-_-________________ 6 Petrology.___--_______-_____-_--__________. 43 Thickness and distribution of younger Precambrian rocks. 7 Criteria for distinguishing basalt from diabase.. 43 Apache Group____________________________________ 11 Pre-Troy unconformity.______---_-___________-.____. 44 Pioneer Shale__________________________________ 11 Troy Quartzite.____________________________________ 44 Thickness and general character-_____________ 11 Definition and subdivision.______________________ -

Hydrogeology of the Tapeats Amphitheater and Deer

HYDROGEOLOGY OF THE TAPEATS AMPHITHEATER AND DEER BASIN, GRAND CANYON, ARIZONA : A STUDY IN KARST HYDROLOGY by Peter Wesley Huntoon A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the COMMITTEE ON HYDROLOGY AND WATER RESOURCES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1968 AC NOWLEDGEMENT The writer gratefully acknowledges Drs . John W . Harshbarger, Jerome J . Wright, Daniel D . Evans and Evans B . Mayo for their careful reading of the manuscript and their many helpful suggestions . t is with deepfelt appreciation that the writer acknowledges his wife, Susan, for the hours she spent in typing this thesis . An assistantship from the Museum of Northern Arizona and a fellowship from the National Defense Education Act, Title V, provided-the funds necessary to carry out this work . TABLE OF CONTENTS Pa aP L ST OF TABLES vii L ST OF LLUSTRAT ONS viii ABSTRACT x NTRODUCT ON 1 Location 1 Topography and Drainage 1 Climate and Vegetation 2 Topographic Maps 4 Accessibility 5 Objectives of the Thesis ' . , 6 Method of Study . 7 Previous Work , , , , , , , , , , , , 7 ROC UN TS : L THOLOG C AND WATER BEAR NG PROPERT ES , , 10 Definition of Permeability 11 Precambrian Rocks 12 Paleozoic Rocks 13 Tonto Group 15 Tapeats Sandstone 15 Bright Angel Shale , 16 Muav Limestone 17 Temple Butte Limestone 19 Redwall Limestone , , , , , , , , , , , , , , 20 Aubrey Group - ' - 22 Supai Formation 23 Hermit Shale 25 Coconino Sandstone , 25 Toroweap Formation 26 aibab Formation 27 Cenozoic