GRAND CANYON GUIDE No. 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hydrogeology of Jurassic and Triassic Wetlands in the Colorado Plateau and the Origin of Tabular Sandstone Uranium Deposits

Hydrogeology of Jurassic and Triassic Wetlands in the Colorado Plateau and the Origin of Tabular Sandstone Uranium Deposits U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1548 AVAILABILITY OF BOOKS AND MAPS OF THE U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Instructions on ordering publications of the U.S. Geological Survey, along with prices of the last offerings, are given in the current-year issues of the monthly catalog "New Publications of the U.S. Geological Survey." Prices of available U.S. Geological Survey publications re leased prior to the current year are listed in the most recent annual "Price and Availability List." Publications that may be listed in various U.S. Geological Survey catalogs (see back inside cover) but not listed in the most recent annual "Price and Availability List" may no longer be available. Reports released through the NTIS may be obtained by writing to the National Technical Information Service, U.S. Department of Commerce, Springfield, VA 22161; please include NTIS report number with inquiry. Order U.S. Geological Survey publications by mail or over the counter from the offices listed below. BY MAIL OVER THE COUNTER Books Books and Maps Professional Papers, Bulletins, Water-Supply Papers, Tech Books and maps of the U.S. Geological Survey are available niques of Water-Resources Investigations, Circulars, publications over the counter at the following U.S. Geological Survey offices, all of general interest (such as leaflets, pamphlets, booklets), single of which are authorized agents of the Superintendent of Docu copies of Earthquakes & Volcanoes, Preliminary Determination of ments. Epicenters, and some miscellaneous reports, including some of the foregoing series that have gone out of print at the Superintendent of Documents, are obtainable by mail from • ANCHORAGE, Alaska-Rm. -

Upper Paleozoic and Cretaceous Stratigraphy of the Hidalgo County Area, New Mexico Eugene Greenwood, F

New Mexico Geological Society Downloaded from: http://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/21 Upper Paleozoic and Cretaceous stratigraphy of the Hidalgo County area, New Mexico Eugene Greenwood, F. E. Kottlowski, and A. K. Armstrong, 1970, pp. 33-44 in: Tyrone, Big Hatchet Mountain, Florida Mountains Region, Woodward, L. A.; [ed.], New Mexico Geological Society 21st Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, 176 p. This is one of many related papers that were included in the 1970 NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebook. Annual NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebooks Every fall since 1950, the New Mexico Geological Society (NMGS) has held an annual Fall Field Conference that explores some region of New Mexico (or surrounding states). Always well attended, these conferences provide a guidebook to participants. Besides detailed road logs, the guidebooks contain many well written, edited, and peer-reviewed geoscience papers. These books have set the national standard for geologic guidebooks and are an essential geologic reference for anyone working in or around New Mexico. Free Downloads NMGS has decided to make peer-reviewed papers from our Fall Field Conference guidebooks available for free download. Non-members will have access to guidebook papers two years after publication. Members have access to all papers. This is in keeping with our mission of promoting interest, research, and cooperation regarding geology in New Mexico. However, guidebook sales represent a significant proportion of our operating budget. Therefore, only research papers are available for download. Road logs, mini-papers, maps, stratigraphic charts, and other selected content are available only in the printed guidebooks. Copyright Information Publications of the New Mexico Geological Society, printed and electronic, are protected by the copyright laws of the United States. -

Quaternary Geology and Geomorphology of the Nankoweap Rapids Area, Marble Canyon, Arizona

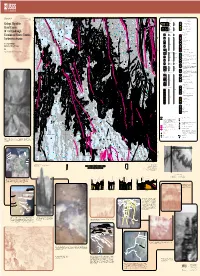

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR TO ACCOMPANY MAP 1-2608 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY QUATERNARY GEOLOGY AND GEOMORPHOLOGY OF THE NANKOWEAP RAPIDS AREA, MARBLE CANYON, ARIZONA By Richard Hereford, Kelly J. Burke, and Kathryn S. Thompson INTRODUCTION sion elsewhere in Grand Canyon {Hereford and oth ers, 1993; Fairley and others, 1994, p. 147-150). The Nankoweap Rapids area along the Colorado River {fig. 1) is near River Mile 52 {that is 52 mi or 83 km downstream of Lees Ferry, Arizona) in Grand Canyon National Park {west bank) and the Navajo METHODS Indian Reservation {east bank). Geologic mapping and [See map sheet for Description of Map Units] related field investigations of the late Quaternary geo morphology of the Colorado River and tributary A variety of methods were used to date the de streams were undertaken to provide information about posits. Radiocarbon dates were obtained from char the age, distribution, and origin of surficial deposits. coal and wood recovered from several of the mapped These deposits, particularly sandy alluvium and closely units (table 1). Several of these dates are not defini related debris-flow sediment, are the substrate for tive as they are affected by extensive animal bur riparian vegetation, which in turn supports the eco rowing in the alluvial deposits that redistributed burnt system of the Colorado River (Carothers and Brown, roots of mesquite trees, giving anomalous dates. The 1991, p. 111-167). late Pleistocene breccia (units be and bf) and re Closure of Glen Canyon Dam {109 km or 68 lated terraces were dated by Machette and Rosholt mi upstream of the study area) in 1963 and subse (1989; 1991) using the uranium-trend method. -

Havasu Canyon Watershed Rapid Watershed Assessment Report June, 2010

Havasu Canyon Watershed Rapid Watershed Assessment Report June, 2010 Prepared by: USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service University of Arizona, Water Resources Research Center In cooperation with: Coconino Natural Resource Conservation District Arizona Department of Agriculture Arizona Department of Environmental Quality Arizona Department of Water Resources Arizona Game & Fish Department Arizona State Land Department USDA Forest Service USDA Bureau of Land Management Released by: Sharon Megdal David L. McKay Director State Conservationist University of Arizona United States Department of Agriculture Water Resources Research Center Natural Resources Conservation Service Principle Investigators: Dino DeSimone – NRCS, Phoenix Keith Larson – NRCS, Phoenix Kristine Uhlman – Water Resources Research Center Terry Sprouse – Water Resources Research Center Phil Guertin – School of Natural Resources The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disa bility, po litica l be lie fs, sexua l or ien ta tion, an d mar ita l or fam ily s ta tus. (No t a ll prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at 202-720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326W, Whitten Building, 14th and Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, D.C., 20250-9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice or TDD). USDA is an equal employment opportunity provider and employer. Havasu Canyon Watershed serve as a platform for conservation 15010004 program delivery, provide useful 8-Digit Hydrologic Unit information for development of NRCS Rapid Watershed Assessment and Conservation District business plans, and lay a foundation for future cooperative watershed planning. -

Michael Kenney Paleozoic Stratigraphy of the Grand Canyon

Michael Kenney Paleozoic Stratigraphy of the Grand Canyon The Paleozoic Era spans about 250 Myrs of Earth History from 541 Ma to 254 Ma (Figure 1). Within Grand Canyon National Park, there is a fragmented record of this time, which has undergone little to no deformation. These still relatively flat-lying, stratified layers, have been the focus of over 100 years of geologic studies. Much of what we know today began with the work of famed naturalist and geologist, Edwin Mckee (Beus and Middleton, 2003). His work, in addition to those before and after, have led to a greater understanding of sedimentation processes, fossil preservation, the evolution of life, and the drastic changes to Earth’s climate during the Paleozoic. This paper seeks to summarize, generally, the Paleozoic strata, the environments in which they were deposited, and the sources from which the sediments were derived. Tapeats Sandstone (~525 Ma – 515 Ma) The Tapeats Sandstone is a buff colored, quartz-rich sandstone and conglomerate, deposited unconformably on the Grand Canyon Supergroup and Vishnu metamorphic basement (Middleton and Elliott, 2003). Thickness varies from ~100 m to ~350 m depending on the paleotopography of the basement rocks upon which the sandstone was deposited. The base of the unit contains the highest abundance of conglomerates. Cobbles and pebbles sourced from the underlying basement rocks are common in the basal unit. Grain size and bed thickness thins upwards (Middleton and Elliott, 2003). Common sedimentary structures include planar and trough cross-bedding, which both decrease in thickness up-sequence. Fossils are rare but within the upper part of the sequence, body fossils date to the early Cambrian (Middleton and Elliott, 2003). -

Harvey Butchart's Hiking Log DETAILED HIKING LOGS (January

Harvey Butchart’s Hiking Log DETAILED HIKING LOGS (January 22, 1965 - September 25, 1965) Mile 24.6 and Hot Na Na Wash [January 22, 1965 to January 23, 1965] My guest for this trip, Norvel Johnson, thought we were going for just the day. When I told him it was a two day trip, he brought in his sleeping bag, but since he had no knapsack, we decided to sleep at the Jeep. The idea was to see Hot Na Na from the rim on Friday and then go down it as far as possible on Saturday. We thought we were following the Tanner Wash Quad map carefully when we left the highway a little to the north of the middle of the bay formed by Curve Wash in the Echo Cliffs. What we didn't realize is that there is another turnoff only a quarter of a mile north of the one we used. This is the way we came out of the hinterland on Saturday. Our exit is marked by a large pile of rocks and it gives a more direct access to all the country we were interested in seeing. The way we went in goes west, south, and north and we got thoroughly confused before we headed toward the rim of Marble Canyon. The track we followed goes considerably past the end of the road which we finally identified as the one that is one and a half miles north of Pine Reservoir. It ended near a dam. We entered the draw beyond the dam and after looking down at the Colorado River, decided that we were on the north side of the bay at Mile 24.6. -

NORTHERN ARIZONA PROVINCE (024) by W.C

NORTHERN ARIZONA PROVINCE (024) By W.C. Butler INTRODUCTION This province covers about 59,000 sq mi, mostly in the southwestern part of the Colorado Plateau. Significant geologic features include the Grand Canyon, Kaibab Arch, Mogollon Highlands transition zone, Monument Uplift, Defiance Uplift, Black Mesa Basin, Holbrook Basin, and southern edges of the Kaiparowits and Blanding Basins. The stratigraphic section shown for northeastern Arizona has demonstrated the highest petroleum potential in Arizona. See Wilson (1962), Butler (1988a), and Dickinson (1989) for synopses of the province's geology and evolution. The lithologically and structurally complex basement of the Colorado Plateau area evolved from northwest-younging Proterozoic terranes sequentially accreted onto the Archean craton. As much as 12,000 ft of Middle and Late Proterozoic strata is preserved in possible rift-aulacogen depositional settings in central Arizona. Thick, unmetamorphosed, organic-rich Late Proterozoic strata deposited in backarc basins or continental lakes of north-central Arizona and south-central Utah have good petroleum potential. The plateau area, as a passive Paleozoic plate margin and buffered Mesozoic retro-arc platform, has been remarkably tectonically stable during Phanerozoic time. The area is characterized by blanket Paleozoic strata, as much as 6,000 ft thick, consisting of mostly shallow marine clastics and carbonates showing numerous disconformities. These strata accumulated during transgressions and regressions from both the northwest and southeast, onlapping and thinning toward the trans-continental arch – a northeast-trending positive area extending from the northeast into central Arizona. Convergence between North and South American tectonic plates, with reactivation of basement blocks, during the late Paleozoic created the plateau's fault-bounded basins and uplifts. -

Grand Canyon

U.S. Department of the Interior Geologic Investigations Series I–2688 14 Version 1.0 4 U.S. Geological Survey 167.5 1 BIG SPRINGS CORRELATION OF MAP UNITS LIST OF MAP UNITS 4 Pt Ph Pamphlet accompanies map .5 Ph SURFICIAL DEPOSITS Pk SURFICIAL DEPOSITS SUPAI MONOCLINE Pk Qr Holocene Qr Colorado River gravel deposits (Holocene) Qsb FAULT CRAZY JUG Pt Qtg Qa Qt Ql Pk Pt Ph MONOCLINE MONOCLINE 18 QUATERNARY Geologic Map of the Pleistocene Qtg Terrace gravel deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Pc Pk Pe 103.5 14 Qa Alluvial deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Pt Pc VOLCANIC ROCKS 45.5 SINYALA Qti Qi TAPEATS FAULT 7 Qhp Qsp Qt Travertine deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Grand Canyon ၧ DE MOTTE FAULT Pc Qtp M u Pt Pleistocene QUATERNARY Pc Qp Pe Qtb Qhb Qsb Ql Landslide deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Qsb 1 Qhp Ph 7 BIG SPRINGS FAULT ′ × ′ 2 VOLCANIC DEPOSITS Dtb Pk PALEOZOIC SEDIMENTARY ROCKS 30 60 Quadrangle, Mr Pc 61 Quaternary basalts (Pleistocene) Unconformity Qsp 49 Pk 6 MUAV FAULT Qhb Pt Lower Tuckup Canyon Basalt (Pleistocene) ၣm TRIASSIC 12 Triassic Qsb Ph Pk Mr Qti Intrusive dikes Coconino and Mohave Counties, Pe 4.5 7 Unconformity 2 3 Pc Qtp Pyroclastic deposits Mr 0.5 1.5 Mၧu EAST KAIBAB MONOCLINE Pk 24.5 Ph 1 222 Qtb Basalt flow Northwestern Arizona FISHTAIL FAULT 1.5 Pt Unconformity Dtb Pc Basalt of Hancock Knolls (Pleistocene) Pe Pe Mၧu Mr Pc Pk Pk Pk NOBLE Pt Qhp Qhb 1 Mၧu Pyroclastic deposits Qhp 5 Pe Pt FAULT Pc Ms 12 Pc 12 10.5 Lower Qhb Basalt flows 1 9 1 0.5 PERMIAN By George H. -

New Hance Trail

National Park Service Grand Canyon U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon National Park Arizona New Hance Trail In 1883, "Captain" John Hance became the first European American to settle at the Grand Canyon. He originally built his trails for mining, but quickly determined the real money lay in work as a guide and hotel manager. From the very start of his tourism business, with his Tennessee drawl, spontaneous wit, uninhibited imagination, and ability to never repeat a tale in exactly the same way, he developed a reputation as an eccentric and highly entertaining storyteller. The scattered presence of abandoned asbestos and copper mines are a reminder of his original intentions for the area. Shortly after his arrival, John improved an old Havasupai trail at the head of today's Hance Creek drainage, the "Old Hance Trail," but it was subject to frequent washouts. When rockslides made it impassable he built the New Hance Trail down Red Canyon. Today's trail very closely follows the trail built in 1894. The New Hance Trail developed a reputation similar to that of the original trail, eliciting the following comment from travel writer Burton Homes in 1904 (he did not exaggerate by much): There may be men who can ride unconcernedly down Hance's Trail, but I confess I am not one of them. My object in descending made it essential that I should live to tell the tale, and therefore, I mustered up sufficient moral courage to dismount and scramble down the steepest and most awful sections of the path on foot …. -

USGS General Information Product

Geologic Field Photograph Map of the Grand Canyon Region, 1967–2010 General Information Product 189 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DAVID BERNHARDT, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey James F. Reilly II, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2019 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. Permission to reproduce copyrighted items must be secured from the copyright owner. Suggested citation: Billingsley, G.H., Goodwin, G., Nagorsen, S.E., Erdman, M.E., and Sherba, J.T., 2019, Geologic field photograph map of the Grand Canyon region, 1967–2010: U.S. Geological Survey General Information Product 189, 11 p., https://doi.org/10.3133/gip189. ISSN 2332-354X (online) Cover. Image EF69 of the photograph collection showing the view from the Tonto Trail (foreground) toward Indian Gardens (greenery), Bright Angel Fault, and Bright Angel Trail, which leads up to the south rim at Grand Canyon Village. Fault offset is down to the east (left) about 200 feet at the rim. -

A Hiker's Companion to GRAND CANYON GEOLOGY

A Hiker’s Companion to GRAND CANYON GEOLOGY With special attention given to The Corridor: North & South Kaibab Trails Bright Angel Trail The geologic history of the Grand Canyon can be approached by breaking it up into three puzzles: 1. How did all those sweet layers get there? 2. How did the area become uplifted over a mile above sea level? 3. How and when was the canyon carved out? That’s how this short guide is organized, into three sections: 1. Laying down the Strata, 2. Uplift, and 3. Carving the Canyon, Followed by a walking geological guide to the 3 most popular hikes in the National Park. I. LAYING DOWN THE STRATA PRE-CAMBRIAN 2000 mya (million years ago), much of the planet’s uppermost layer was thin oceanic crust, and plate tectonics was functioning more or less as it does now. It begins with a Subduction Zone... Vishnu Schist: 1840 mya, the GC region was the site of an active subduction zone, crowned by a long volcanic chain known as the Yavapai Arc (similar to today’s Aleutian Islands). The oceanic crust on the leading edge of Wyomingland, a huge plate driving in from the NW, was subducting under another plate at the zone, a terrane known as the Yavapai Province. Subduction brought Wyomingland closer and closer to the arc for 150 million years, during which genera- tions of volcanoes were born and laid dormant along the arc. Lava and ash of new volcanoes mixed with the eroded sands and mud from older cones, creating a pile of inter-bedded lava, ash, sand, and mud that was 40,000 feet deep! Vishnu Schist Zoroaster Granite Wyomingland reached the subduction zone 1700 mya. -

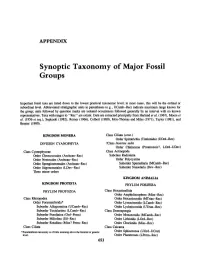

Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups

APPENDIX Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups Important fossil taxa are listed down to the lowest practical taxonomic level; in most cases, this will be the ordinal or subordinallevel. Abbreviated stratigraphic units in parentheses (e.g., UCamb-Ree) indicate maximum range known for the group; units followed by question marks are isolated occurrences followed generally by an interval with no known representatives. Taxa with ranges to "Ree" are extant. Data are extracted principally from Harland et al. (1967), Moore et al. (1956 et seq.), Sepkoski (1982), Romer (1966), Colbert (1980), Moy-Thomas and Miles (1971), Taylor (1981), and Brasier (1980). KINGDOM MONERA Class Ciliata (cont.) Order Spirotrichia (Tintinnida) (UOrd-Rec) DIVISION CYANOPHYTA ?Class [mertae sedis Order Chitinozoa (Proterozoic?, LOrd-UDev) Class Cyanophyceae Class Actinopoda Order Chroococcales (Archean-Rec) Subclass Radiolaria Order Nostocales (Archean-Ree) Order Polycystina Order Spongiostromales (Archean-Ree) Suborder Spumellaria (MCamb-Rec) Order Stigonematales (LDev-Rec) Suborder Nasselaria (Dev-Ree) Three minor orders KINGDOM ANIMALIA KINGDOM PROTISTA PHYLUM PORIFERA PHYLUM PROTOZOA Class Hexactinellida Order Amphidiscophora (Miss-Ree) Class Rhizopodea Order Hexactinosida (MTrias-Rec) Order Foraminiferida* Order Lyssacinosida (LCamb-Rec) Suborder Allogromiina (UCamb-Ree) Order Lychniscosida (UTrias-Rec) Suborder Textulariina (LCamb-Ree) Class Demospongia Suborder Fusulinina (Ord-Perm) Order Monaxonida (MCamb-Ree) Suborder Miliolina (Sil-Ree) Order Lithistida