Harvey Butchart's Hiking Log DETAILED HIKING LOGS (January

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grand-Canyon-South-Rim-Map.Pdf

North Rim (see enlargement above) KAIBAB PLATEAU Point Imperial KAIBAB PLATEAU 8803ft Grama Point 2683 m Dragon Head North Rim Bright Angel Vista Encantada Point Sublime 7770 ft Point 7459 ft Tiyo Point Widforss Point Visitor Center 8480ft Confucius Temple 2368m 7900 ft 2585 m 2274 m 7766 ft Grand Canyon Lodge 7081 ft Shiva Temple 2367 m 2403 m Obi Point Chuar Butte Buddha Temple 6394ft Colorado River 2159 m 7570 ft 7928 ft Cape Solitude Little 2308m 7204 ft 2417 m Francois Matthes Point WALHALLA PLATEAU 1949m HINDU 2196 m 8020 ft 6144ft 2445 m 1873m AMPHITHEATER N Cape Final Temple of Osiris YO Temple of Ra Isis Temple N 7916ft From 6637 ft CA Temple Butte 6078 ft 7014 ft L 2413 m Lake 1853 m 2023 m 2138 m Hillers Butte GE Walhalla Overlook 5308ft Powell T N Brahma Temple 7998ft Jupiter Temple 1618m ri 5885 ft A ni T 7851ft Thor Temple ty H 2438 m 7081ft GR 1794 m G 2302 m 6741 ft ANIT I 2158 m E C R Cape Royal PALISADES OF GO r B Zoroaster Temple 2055m RG e k 7865 ft E Tower of Set e ee 7129 ft Venus Temple THE DESERT To k r C 2398 m 6257ft Lake 6026 ft Cheops Pyramid l 2173 m N Pha e Freya Castle Espejo Butte g O 1907 m Mead 1837m 5399 ft nto n m A Y t 7299 ft 1646m C N reek gh Sumner Butte Wotans Throne 2225m Apollo Temple i A Br OTTOMAN 5156 ft C 7633 ft 1572 m AMPHITHEATER 2327 m 2546 ft R E Cocopa Point 768 m T Angels Vishnu Temple Comanche Point M S Co TONTO PLATFOR 6800 ft Phantom Ranch Gate 7829 ft 7073ft lor 2073 m A ado O 2386 m 2156m R Yuma Point Riv Hopi ek er O e 6646 ft Z r Pima Mohave Point Maricopa C Krishna Shrine T -

Tanner to the Little Colorado River

Tanner to the Little Colorado River Natural History Backpack April 3-9, 2020 with Melissa Giovanni CLASS INFORMATION AND SYLLABUS DAY 1 Meet at 10:00 a.m. at the historic Community This class focuses on the geology, anthropology, Building in Grand Canyon Village (Google Map). ecology, and history of eastern Grand Canyon. We will orient ourselves to the trip and learn some This route is unique among South Rim hikes due basic concepts of geology as well. We will first to the stunning exposures of most of the major spend some time on introductions and gear, food, rock groups that compose the walls of Grand and the class. After lunch we will have a short Canyon. While we will not be able to view the session in the classroom and then go out to the deepest and innermost crystalline and rim (and perhaps partway down one of the major metamorphic rocks, we will see exposures of the trails) to become familiar with regional geography younger Precambrian strata unequaled anywhere and landmarks. We will also cover fundamental else. geology tenets that lay the ground work for the rest of the class, including: The class also provides superb views of underlying structural features, including faults, A geographic overview of the region unconformities, and intrusions not visible The three rock families; how they form and elsewhere. We will see one of the most profound how this is reflected in their appearance faults in Grand Canyon, one that may have played The principles of stratigraphy a major role in the formation of the canyon itself. -

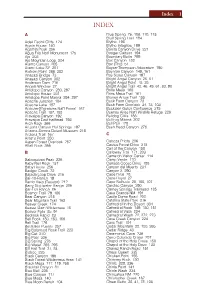

Index 1 INDEX

Index 1 INDEX A Blue Spring 76, 106, 110, 115 Bluff Spring Trail 184 Adeii Eechii Cliffs 124 Blythe 198 Agate House 140 Blythe Intaglios 199 Agathla Peak 256 Bonita Canyon Drive 221 Agua Fria Nat'l Monument 175 Booger Canyon 194 Ajo 203 Boundary Butte 299 Ajo Mountain Loop 204 Box Canyon 132 Alamo Canyon 205 Box (The) 51 Alamo Lake SP 201 Boyce-Thompson Arboretum 190 Alstrom Point 266, 302 Boynton Canyon 149, 161 Anasazi Bridge 73 Boy Scout Canyon 197 Anasazi Canyon 302 Bright Angel Canyon 25, 51 Anderson Dam 216 Bright Angel Point 15, 25 Angels Window 27 Bright Angel Trail 42, 46, 49, 61, 80, 90 Antelope Canyon 280, 297 Brins Mesa 160 Antelope House 231 Brins Mesa Trail 161 Antelope Point Marina 294, 297 Broken Arrow Trail 155 Apache Junction 184 Buck Farm Canyon 73 Apache Lake 187 Buck Farm Overlook 34, 73, 103 Apache-Sitgreaves Nat'l Forest 167 Buckskin Gulch Confluence 275 Apache Trail 187, 188 Buenos Aires Nat'l Wildlife Refuge 226 Aravaipa Canyon 192 Bulldog Cliffs 186 Aravaipa East trailhead 193 Bullfrog Marina 302 Arch Rock 366 Bull Pen 170 Arizona Canyon Hot Springs 197 Bush Head Canyon 278 Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum 216 Arizona Trail 167 C Artist's Point 250 Aspen Forest Overlook 257 Cabeza Prieta 206 Atlatl Rock 366 Cactus Forest Drive 218 Call of the Canyon 158 B Calloway Trail 171, 203 Cameron Visitor Center 114 Baboquivari Peak 226 Camp Verde 170 Baby Bell Rock 157 Canada Goose Drive 198 Baby Rocks 256 Canyon del Muerto 231 Badger Creek 72 Canyon X 290 Bajada Loop Drive 216 Cape Final 28 Bar-10-Ranch 19 Cape Royal 27 Barrio -

Thunder River - One of the Top Ten Backpacking Destinations

1 Thunder River - One of the Top Ten Backpacking Destinations “Like a gift from God, booming streams of crystalline water emerge from mysterious caves to transform the harsh desert of the inner canyon into absurdly beautiful green oasis….” Chi S. Chan October 2015 2 It is 7:00am in the morning, the sun already blasts over the rim rock and begins to warm, but only modest warmth, barely enough to take the edge off. Its light is brilliant, harsh. “It is going to be a long day”, Vince, our leader, casually reminds us. He hoists his backpack and glances over to the North Rim. If he really worries about our group’s ability to finish this hike, he definitely does not show it. His confidence in us grows each day as we overcome one obstacle after another. It all begins on day one. Mountain Sheep Spring Life-giving source of water The weather man predicts the rain, but no one takes the warning seriously. Rain storm in the desert usually passes as quickly as it comes. A few splash of rainfall is not going to deter us. It rains briefly when we reach our first camp. Our site sits on a dried river bed. No one knows when the last rain reached this part of the canyon. It appears to be a completely safe dry camp. Vince and his older brother Bill, who is also our assistant leader, set up their tent on the edge of the river bed. On the eastern side of the canyon, a few small alcoves provide resting quarter. -

Grand Canyon

ALT ALT To 389 To 389 To Jacob Lake, 89 To 89 K and South Rim a n a b Unpaved roads are impassable when wet. C Road closed r KAIBAB NATIONAL FOREST e in winter e K k L EA O N R O O B K NY O A E U C C N T E N C 67 I A H M N UT E Y SO N K O O A N House Rock Y N N A Buffalo Ranch B A KANAB PLATEAU C C E A L To St. George, Utah N B Y Kaibab Lodge R Mount Trumbull O A N KAIBAB M 8028ft De Motte C 2447m (USFS) O er GR C o Riv AN T PLATEAU K HUNDRED AND FIFTY MIL lorad ITE ap S NAVAJO E Co N eat C A s C Y RR C N O OW ree S k M INDIAN GRAND CANYON NATIONAL PARK B T Steamboat U Great Thumb Point Mountain C RESERVATION K 6749ft 7422ft U GREAT THUMB 2057m 2262m P Chikapanagi Point MESA C North Rim A 5889ft E N G Entrance Station 1795m M Y 1880ft FOSSIL R 8824ft O Mount Sinyala O U 573m G A k TUCKUP N 5434ft BAY Stanton Point e 2690m V re POINT 1656m 6311ft E U C SB T A C k 1924m I E e C N AT A e The Dome POINT A PL N r o L Y Holy Grail l 5486ft R EL Point Imperial C o Tuweep G W O Temple r 1672m PO N Nankoweap a p d H E o wea Mesa A L nko o V a Mooney D m N 6242ft A ID Mount Emma S Falls u 1903m U M n 7698ft i Havasu Falls h 2346m k TOROWEAP er C Navajo Falls GORGE S e v A Vista e i ITE r Kwagunt R VALLEY R N N Supai Falls A Encantada C iv o Y R nt Butte W d u e a O G g lor Supai 2159ft Unpaved roads are North Rim wa 6377ft r o N K h C Reservations required. -

Summits on the Air – ARM for the USA (W7A

Summits on the Air – ARM for the U.S.A (W7A - Arizona) Summits on the Air U.S.A. (W7A - Arizona) Association Reference Manual Document Reference S53.1 Issue number 5.0 Date of issue 31-October 2020 Participation start date 01-Aug 2010 Authorized Date: 31-October 2020 Association Manager Pete Scola, WA7JTM Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged. Document S53.1 Page 1 of 15 Summits on the Air – ARM for the U.S.A (W7A - Arizona) TABLE OF CONTENTS CHANGE CONTROL....................................................................................................................................... 3 DISCLAIMER................................................................................................................................................. 4 1 ASSOCIATION REFERENCE DATA ........................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Program Derivation ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 General Information ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Final Ascent -

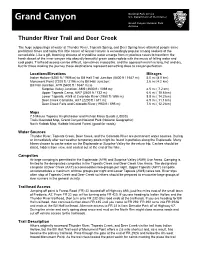

Thunder River Trail and Deer Creek

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon Grand Canyon National Park Arizona Thunder River Trail and Deer Creek The huge outpourings of water at Thunder River, Tapeats Spring, and Deer Spring have attracted people since prehistoric times and today this little corner of Grand Canyon is exceedingly popular among seekers of the remarkable. Like a gift, booming streams of crystalline water emerge from mysterious caves to transform the harsh desert of the inner canyon into absurdly beautiful green oasis replete with the music of falling water and cool pools. Trailhead access can be difficult, sometimes impossible, and the approach march is long, hot and dry, but for those making the journey these destinations represent something close to canyon perfection. Locations/Elevations Mileages Indian Hollow (6250 ft / 1906 m) to Bill Hall Trail Junction (5400 ft / 1647 m): 5.0 mi (8.0 km) Monument Point (7200 ft / 2196 m) to Bill Hall Junction: 2.6 mi (4.2 km) Bill Hall Junction, AY9 (5400 ft / 1647 m) to Surprise Valley Junction, AM9 (3600 ft / 1098 m): 4.5 mi ( 7.2 km) Upper Tapeats Camp, AW7 (2400 ft / 732 m): 6.6 mi ( 10.6 km) Lower Tapeats, AW8 at Colorado River (1950 ft / 595 m): 8.8 mi ( 14.2 km) Deer Creek Campsite, AX7 (2200 ft / 671 m): 6.9 mi ( 11.1 km) Deer Creek Falls and Colorado River (1950 ft / 595 m): 7.6 mi ( 12.2 km) Maps 7.5 Minute Tapeats Amphitheater and Fishtail Mesa Quads (USGS) Trails Illustrated Map, Grand Canyon National Park (National Geographic) North Kaibab Map, Kaibab National Forest (good for roads) Water Sources Thunder River, Tapeats Creek, Deer Creek, and the Colorado River are permanent water sources. -

GRAND CANYON GUIDE No. 6

GRAND CANYON GUIDE no. 6 ... excerpted from Grand Canyon Explorer … Bob Ribokas AN AMATEUR'S REVIEW OF BACKPACKING TOPICS FOR THE T254 - EXPEDITION TO THE GRAND CANYON - MARCH 2007 Descriptions of Grand Canyon Layers Grand Canyon attracts the attention of the world for many reasons, but perhaps its greatest significance lies in the geologic record that is so beautifully preserved and exposed here. The rocks at Grand Canyon are not inherently unique; similar rocks are found throughout the world. What is unique about the geologic record at Grand Canyon is the great variety of rocks present, the clarity with which they're exposed, and the complex geologic story they tell. Paleozoic Strata: Kaibab depositional environment: Kaibab Limestone - This layer forms the surface of the Kaibab and Coconino Plateaus. It is composed primarily of a sandy limestone with a layer of sandstone below it. In some places sandstone and shale also exists as its upper layer. The color ranges from cream to a greyish-white. When viewed from the rim this layer resembles a bathtub ring and is commonly referred to as the Canyon's bathtub ring. Fossils that can be found in this layer are brachiopods, coral, mollusks, sea lilies, worms and fish teeth. Toroweap depositional environment Toroweap Formation - This layer is composed of pretty much the same material as the Kaibab Limestone above. It is darker in color, ranging from yellow to grey, and contains a similar fossil history. Coconino depositional environment: Coconino Sandstone - This layer is composed of pure quartz sand, which are basically petrified sand dunes. Wedge-shaped cross bedding can be seen where traverse-type dunes have been petrified. -

Geographic Names

GEOGRAPHIC NAMES CORRECT ORTHOGRAPHY OF GEOGRAPHIC NAMES ? REVISED TO JANUARY, 1911 WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1911 PREPARED FOR USE IN THE GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE BY THE UNITED STATES GEOGRAPHIC BOARD WASHINGTON, D. C, JANUARY, 1911 ) CORRECT ORTHOGRAPHY OF GEOGRAPHIC NAMES. The following list of geographic names includes all decisions on spelling rendered by the United States Geographic Board to and including December 7, 1910. Adopted forms are shown by bold-face type, rejected forms by italic, and revisions of previous decisions by an asterisk (*). Aalplaus ; see Alplaus. Acoma; township, McLeod County, Minn. Abagadasset; point, Kennebec River, Saga- (Not Aconia.) dahoc County, Me. (Not Abagadusset. AQores ; see Azores. Abatan; river, southwest part of Bohol, Acquasco; see Aquaseo. discharging into Maribojoc Bay. (Not Acquia; see Aquia. Abalan nor Abalon.) Acworth; railroad station and town, Cobb Aberjona; river, IVIiddlesex County, Mass. County, Ga. (Not Ackworth.) (Not Abbajona.) Adam; island, Chesapeake Bay, Dorchester Abino; point, in Canada, near east end of County, Md. (Not Adam's nor Adams.) Lake Erie. (Not Abineau nor Albino.) Adams; creek, Chatham County, Ga. (Not Aboite; railroad station, Allen County, Adams's.) Ind. (Not Aboit.) Adams; township. Warren County, Ind. AJjoo-shehr ; see Bushire. (Not J. Q. Adams.) Abookeer; AhouJcir; see Abukir. Adam's Creek; see Cunningham. Ahou Hamad; see Abu Hamed. Adams Fall; ledge in New Haven Harbor, Fall.) Abram ; creek in Grant and Mineral Coun- Conn. (Not Adam's ties, W. Va. (Not Abraham.) Adel; see Somali. Abram; see Shimmo. Adelina; town, Calvert County, Md. (Not Abruad ; see Riad. Adalina.) Absaroka; range of mountains in and near Aderhold; ferry over Chattahoochee River, Yellowstone National Park. -

1988 Backcountry Management Plan

Backcountry Management Plan September 1988 Grand Canyon National Park Arizona National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior (this version of the Backcountry Management Plan was reformatted in April 2000) Recommended by: Richard Marks, Superintendent, Grand Canyon National Park, 8/8/88 Approved by: Stanley T Albright, Regional Director Western Region, 8/9/88 2 GRAND CANYON NATIONAL PARK 1988 BACKCOUNTRY MANAGEMENT PLAN Table of Contents A. Introduction __________________________________________________________________ 4 B. Goals ________________________________________________________________________ 4 C. Legislation and NPS Policy ______________________________________________________ 5 D. Backcountry Zoning and Use Areas _______________________________________________ 6 E. Reservation and Permit System __________________________________________________ 6 F. Visitor Use Limits ______________________________________________________________7 G.Use Limit Explanations for Selected Use Areas _____________________________________ 8 H.Visitor Activity Restrictions _____________________________________________________ 9 I. Information, Education and Enforcement_________________________________________ 13 J. Resource Protection, Monitoring, and Research ___________________________________ 14 K. Plan Review and Update _______________________________________________________15 Appendix A Backcountry Zoning and Use Limits __________________________________ 16 Appendix B Backcountry Reservation and Permit System __________________________ 20 -

Grand Canyon

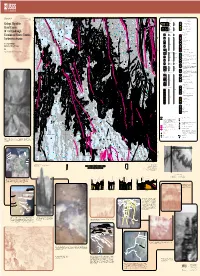

U.S. Department of the Interior Geologic Investigations Series I–2688 14 Version 1.0 4 U.S. Geological Survey 167.5 1 BIG SPRINGS CORRELATION OF MAP UNITS LIST OF MAP UNITS 4 Pt Ph Pamphlet accompanies map .5 Ph SURFICIAL DEPOSITS Pk SURFICIAL DEPOSITS SUPAI MONOCLINE Pk Qr Holocene Qr Colorado River gravel deposits (Holocene) Qsb FAULT CRAZY JUG Pt Qtg Qa Qt Ql Pk Pt Ph MONOCLINE MONOCLINE 18 QUATERNARY Geologic Map of the Pleistocene Qtg Terrace gravel deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Pc Pk Pe 103.5 14 Qa Alluvial deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Pt Pc VOLCANIC ROCKS 45.5 SINYALA Qti Qi TAPEATS FAULT 7 Qhp Qsp Qt Travertine deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Grand Canyon ၧ DE MOTTE FAULT Pc Qtp M u Pt Pleistocene QUATERNARY Pc Qp Pe Qtb Qhb Qsb Ql Landslide deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Qsb 1 Qhp Ph 7 BIG SPRINGS FAULT ′ × ′ 2 VOLCANIC DEPOSITS Dtb Pk PALEOZOIC SEDIMENTARY ROCKS 30 60 Quadrangle, Mr Pc 61 Quaternary basalts (Pleistocene) Unconformity Qsp 49 Pk 6 MUAV FAULT Qhb Pt Lower Tuckup Canyon Basalt (Pleistocene) ၣm TRIASSIC 12 Triassic Qsb Ph Pk Mr Qti Intrusive dikes Coconino and Mohave Counties, Pe 4.5 7 Unconformity 2 3 Pc Qtp Pyroclastic deposits Mr 0.5 1.5 Mၧu EAST KAIBAB MONOCLINE Pk 24.5 Ph 1 222 Qtb Basalt flow Northwestern Arizona FISHTAIL FAULT 1.5 Pt Unconformity Dtb Pc Basalt of Hancock Knolls (Pleistocene) Pe Pe Mၧu Mr Pc Pk Pk Pk NOBLE Pt Qhp Qhb 1 Mၧu Pyroclastic deposits Qhp 5 Pe Pt FAULT Pc Ms 12 Pc 12 10.5 Lower Qhb Basalt flows 1 9 1 0.5 PERMIAN By George H. -

South Kaibab Trail, Grand Canyon

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon Grand Canyon National Park Arizona South Kaibab Trail Hikers seeking panoramic views unparalleled on any other trail at Grand Canyon will want to consider a hike down the South Kaibab Trail. It is the only trail at Grand Canyon National Park that so dramatically holds true to a ridgeline descent. But this exhilarating sense of exposure to the vastness of the canyon comes at a cost: there is little shade and no water for the length of this trail. During winter months, the constant sun exposure is likely to keep most of the trail relatively free of ice and snow. For those who insist on hiking during summer months, which is not recommended in general, this trail is the quickest way to the bottom (it has been described as "a trail in a hurry to get to the river"), but due to lack of any water sources, ascending the trail can be a dangerous proposition. The South Kaibab Trail is a modern route, having been constructed as a means by which park visitors could bypass Ralph Cameron's Bright Angel Trail. Cameron, who owned the Bright Angel Trail and charged a toll to those using it, fought dozens of legal battles over several decades to maintain his personal business rights. These legal battles inspired the Santa Fe Railroad to build its own alternative trail, the Hermit Trail, beginning in 1911 before the National Park Service went on to build the South Kaibab Trail beginning in 1924. In this way, Cameron inadvertently contributed much to the greater network of trails currently available for use by canyon visitors.