Sedimentological Interpretation of the Tonto Group Stratigraphy (Grand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 2 Paleozoic Stratigraphy of the Grand Canyon

CHAPTER 2 PALEOZOIC STRATIGRAPHY OF THE GRAND CANYON PAIGE KERCHER INTRODUCTION The Paleozoic Era of the Phanerozoic Eon is defined as the time between 542 and 251 million years before the present (ICS 2010). The Paleozoic Era began with the evolution of most major animal phyla present today, sparked by the novel adaptation of skeletal hard parts. Organisms continued to diversify throughout the Paleozoic into increasingly adaptive and complex life forms, including the first vertebrates, terrestrial plants and animals, forests and seed plants, reptiles, and flying insects. Vast coal swamps covered much of mid- to low-latitude continental environments in the late Paleozoic as the supercontinent Pangaea began to amalgamate. The hardiest taxa survived the multiple global glaciations and mass extinctions that have come to define major time boundaries of this era. Paleozoic North America existed primarily at mid to low latitudes and experienced multiple major orogenies and continental collisions. For much of the Paleozoic, North America’s southwestern margin ran through Nevada and Arizona – California did not yet exist (Appendix B). The flat-lying Paleozoic rocks of the Grand Canyon, though incomplete, form a record of a continental margin repeatedly inundated and vacated by shallow seas (Appendix A). IMPORTANT STRATIGRAPHIC PRINCIPLES AND CONCEPTS • Principle of Original Horizontality – In most cases, depositional processes produce flat-lying sedimentary layers. Notable exceptions include blanketing ash sheets, and cross-stratification developed on sloped surfaces. • Principle of Superposition – In an undisturbed sequence, older strata lie below younger strata; a package of sedimentary layers youngs upward. • Principle of Lateral Continuity – A layer of sediment extends laterally in all directions until it naturally pinches out or abuts the walls of its confining basin. -

Michael Kenney Paleozoic Stratigraphy of the Grand Canyon

Michael Kenney Paleozoic Stratigraphy of the Grand Canyon The Paleozoic Era spans about 250 Myrs of Earth History from 541 Ma to 254 Ma (Figure 1). Within Grand Canyon National Park, there is a fragmented record of this time, which has undergone little to no deformation. These still relatively flat-lying, stratified layers, have been the focus of over 100 years of geologic studies. Much of what we know today began with the work of famed naturalist and geologist, Edwin Mckee (Beus and Middleton, 2003). His work, in addition to those before and after, have led to a greater understanding of sedimentation processes, fossil preservation, the evolution of life, and the drastic changes to Earth’s climate during the Paleozoic. This paper seeks to summarize, generally, the Paleozoic strata, the environments in which they were deposited, and the sources from which the sediments were derived. Tapeats Sandstone (~525 Ma – 515 Ma) The Tapeats Sandstone is a buff colored, quartz-rich sandstone and conglomerate, deposited unconformably on the Grand Canyon Supergroup and Vishnu metamorphic basement (Middleton and Elliott, 2003). Thickness varies from ~100 m to ~350 m depending on the paleotopography of the basement rocks upon which the sandstone was deposited. The base of the unit contains the highest abundance of conglomerates. Cobbles and pebbles sourced from the underlying basement rocks are common in the basal unit. Grain size and bed thickness thins upwards (Middleton and Elliott, 2003). Common sedimentary structures include planar and trough cross-bedding, which both decrease in thickness up-sequence. Fossils are rare but within the upper part of the sequence, body fossils date to the early Cambrian (Middleton and Elliott, 2003). -

Grand Canyon

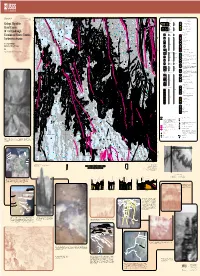

U.S. Department of the Interior Geologic Investigations Series I–2688 14 Version 1.0 4 U.S. Geological Survey 167.5 1 BIG SPRINGS CORRELATION OF MAP UNITS LIST OF MAP UNITS 4 Pt Ph Pamphlet accompanies map .5 Ph SURFICIAL DEPOSITS Pk SURFICIAL DEPOSITS SUPAI MONOCLINE Pk Qr Holocene Qr Colorado River gravel deposits (Holocene) Qsb FAULT CRAZY JUG Pt Qtg Qa Qt Ql Pk Pt Ph MONOCLINE MONOCLINE 18 QUATERNARY Geologic Map of the Pleistocene Qtg Terrace gravel deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Pc Pk Pe 103.5 14 Qa Alluvial deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Pt Pc VOLCANIC ROCKS 45.5 SINYALA Qti Qi TAPEATS FAULT 7 Qhp Qsp Qt Travertine deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Grand Canyon ၧ DE MOTTE FAULT Pc Qtp M u Pt Pleistocene QUATERNARY Pc Qp Pe Qtb Qhb Qsb Ql Landslide deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Qsb 1 Qhp Ph 7 BIG SPRINGS FAULT ′ × ′ 2 VOLCANIC DEPOSITS Dtb Pk PALEOZOIC SEDIMENTARY ROCKS 30 60 Quadrangle, Mr Pc 61 Quaternary basalts (Pleistocene) Unconformity Qsp 49 Pk 6 MUAV FAULT Qhb Pt Lower Tuckup Canyon Basalt (Pleistocene) ၣm TRIASSIC 12 Triassic Qsb Ph Pk Mr Qti Intrusive dikes Coconino and Mohave Counties, Pe 4.5 7 Unconformity 2 3 Pc Qtp Pyroclastic deposits Mr 0.5 1.5 Mၧu EAST KAIBAB MONOCLINE Pk 24.5 Ph 1 222 Qtb Basalt flow Northwestern Arizona FISHTAIL FAULT 1.5 Pt Unconformity Dtb Pc Basalt of Hancock Knolls (Pleistocene) Pe Pe Mၧu Mr Pc Pk Pk Pk NOBLE Pt Qhp Qhb 1 Mၧu Pyroclastic deposits Qhp 5 Pe Pt FAULT Pc Ms 12 Pc 12 10.5 Lower Qhb Basalt flows 1 9 1 0.5 PERMIAN By George H. -

An Inventory of Trilobites from National Park Service Areas

Sullivan, R.M. and Lucas, S.G., eds., 2016, Fossil Record 5. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 74. 179 AN INVENTORY OF TRILOBITES FROM NATIONAL PARK SERVICE AREAS MEGAN R. NORR¹, VINCENT L. SANTUCCI1 and JUSTIN S. TWEET2 1National Park Service. 1201 Eye Street NW, Washington, D.C. 20005; -email: [email protected]; 2Tweet Paleo-Consulting. 9149 79th St. S. Cottage Grove. MN 55016; Abstract—Trilobites represent an extinct group of Paleozoic marine invertebrate fossils that have great scientific interest and public appeal. Trilobites exhibit wide taxonomic diversity and are contained within nine orders of the Class Trilobita. A wealth of scientific literature exists regarding trilobites, their morphology, biostratigraphy, indicators of paleoenvironments, behavior, and other research themes. An inventory of National Park Service areas reveals that fossilized remains of trilobites are documented from within at least 33 NPS units, including Death Valley National Park, Grand Canyon National Park, Yellowstone National Park, and Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve. More than 120 trilobite hototype specimens are known from National Park Service areas. INTRODUCTION Of the 262 National Park Service areas identified with paleontological resources, 33 of those units have documented trilobite fossils (Fig. 1). More than 120 holotype specimens of trilobites have been found within National Park Service (NPS) units. Once thriving during the Paleozoic Era (between ~520 and 250 million years ago) and becoming extinct at the end of the Permian Period, trilobites were prone to fossilization due to their hard exoskeletons and the sedimentary marine environments they inhabited. While parks such as Death Valley National Park and Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve have reported a great abundance of fossilized trilobites, many other national parks also contain a diverse trilobite fauna. -

USGS General Information Product

Geologic Field Photograph Map of the Grand Canyon Region, 1967–2010 General Information Product 189 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DAVID BERNHARDT, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey James F. Reilly II, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2019 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. Permission to reproduce copyrighted items must be secured from the copyright owner. Suggested citation: Billingsley, G.H., Goodwin, G., Nagorsen, S.E., Erdman, M.E., and Sherba, J.T., 2019, Geologic field photograph map of the Grand Canyon region, 1967–2010: U.S. Geological Survey General Information Product 189, 11 p., https://doi.org/10.3133/gip189. ISSN 2332-354X (online) Cover. Image EF69 of the photograph collection showing the view from the Tonto Trail (foreground) toward Indian Gardens (greenery), Bright Angel Fault, and Bright Angel Trail, which leads up to the south rim at Grand Canyon Village. Fault offset is down to the east (left) about 200 feet at the rim. -

Deposition of the Tapeats Sandstone (Cambrian) in Central Arizona

Deposition of the Tapeats Sandstone (Cambrian) in central Arizona RICHARD HEREFORD U.S. Geological Survey, 601 East Cedar Avenue, Flagstaff, Arizona 86001 ABSTRACT stratigraphy of the Tapeats Sandstone in Bright Angel Shale and Muav Limestone central Arizona. This area lies along the are absent, and the Tapeats Sandstone is Grain size, bedding thickness, dispersion southern margin of the Colorado Plateau overlain unconformably by the Chino Val- of cross-stratification azimuths, and as- and includes most of the headwaters and ley Formation that was thought to be of semblages of sedimentary structures and northern reaches of the Verde and East probable Cambrian age when defined by trace fossils vary across central Arizona; Verde Rivers (Fig. 1). Hereford (1975). The results of this study they form the basis for recognizing six Relatively thin Cambrian sandstone de- indicate that the Chino Valley Formation facies (A through F) in the Tapeats posits such as the Tapeats are the basal and Tapeats Sandstone are separated by a Sandstone. Five of these (A through E), coarse-grained facies of a transgressive se- major stratigraphic break which probably present in western central Arizona, are quence that extended along north-trending spans several periods. marine deposits containing the trace fossil strandlines throughout the Rocky This study is restricted to data obtainable Corophioides; several intertidal environ- Mountain states (Lochman-Balk, 1971, p. through field observations, such as the ments are represented. The association of 95 — 103). -

Hydrogeology of the Tapeats Amphitheater and Deer

HYDROGEOLOGY OF THE TAPEATS AMPHITHEATER AND DEER BASIN, GRAND CANYON, ARIZONA : A STUDY IN KARST HYDROLOGY by Peter Wesley Huntoon A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the COMMITTEE ON HYDROLOGY AND WATER RESOURCES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1968 AC NOWLEDGEMENT The writer gratefully acknowledges Drs . John W . Harshbarger, Jerome J . Wright, Daniel D . Evans and Evans B . Mayo for their careful reading of the manuscript and their many helpful suggestions . t is with deepfelt appreciation that the writer acknowledges his wife, Susan, for the hours she spent in typing this thesis . An assistantship from the Museum of Northern Arizona and a fellowship from the National Defense Education Act, Title V, provided-the funds necessary to carry out this work . TABLE OF CONTENTS Pa aP L ST OF TABLES vii L ST OF LLUSTRAT ONS viii ABSTRACT x NTRODUCT ON 1 Location 1 Topography and Drainage 1 Climate and Vegetation 2 Topographic Maps 4 Accessibility 5 Objectives of the Thesis ' . , 6 Method of Study . 7 Previous Work , , , , , , , , , , , , 7 ROC UN TS : L THOLOG C AND WATER BEAR NG PROPERT ES , , 10 Definition of Permeability 11 Precambrian Rocks 12 Paleozoic Rocks 13 Tonto Group 15 Tapeats Sandstone 15 Bright Angel Shale , 16 Muav Limestone 17 Temple Butte Limestone 19 Redwall Limestone , , , , , , , , , , , , , , 20 Aubrey Group - ' - 22 Supai Formation 23 Hermit Shale 25 Coconino Sandstone , 25 Toroweap Formation 26 aibab Formation 27 Cenozoic -

Resume of the Geology of Arizona," Prepared by Dr

, , A RESUME of the GEOWGY OF ARIZONA by Eldred D. Wilson, Geologist THE ARIZONA BUREAU OF MINES Bulletin 171 1962 THB UNIVBR.ITY OP ARIZONA. PR••• _ TUC.ON FOREWORD CONTENTS Page This "Resume of the Geology of Arizona," prepared by Dr. Eldred FOREWORD _................................................................................................ ii D. Wilson, Geologist, Arizona Bureau of Mines, is a notable contribution LIST OF TABLES viii to the geologic and mineral resource literature about Arizona. It com LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS viii prises a thorough and comprehensive survey of the natural processes and phenomena that have prevailed to establish the present physical setting CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION Purpose and scope I of the State and it will serve as a splendid base reference for continued, Previous work I detailed studies which will follow. Early explorations 1 The Arizona Bureau of Mines is pleased to issue the work as Bulletin Work by U.S. Geological Survey.......................................................... 2 171 of its series of technical publications. Research by University of Arizona 2 Work by Arizona Bureau of Mines 2 Acknowledgments 3 J. D. Forrester, Director Arizona Bureau of Mines CHAPTER -II: ROCK UNITS, STRUCTURE, AND ECONOMIC FEATURES September 1962 Time divisions 5 General statement 5 Methods of dating and correlating 5 Systems of folding and faulting 5 Precambrian Eras ".... 7 General statement 7 Older Precambrian Era 10 Introduction 10 Literature 10 Age assignment 10 Geosynclinal development 10 Mazatzal Revolution 11 Intra-Precambrian Interval 13 Younger Precambrian Era 13 Units and correlation 13 Structural development 17 General statement 17 Grand Canyon Disturbance 17 Economic features of Arizona Precambrian 19 COPYRIGHT@ 1962 Older Precambrian 19 The Board of Regents of the Universities and Younger Precambrian 20 State College of Arizona. -

62. Origin of Horseshoe Bend, Arizona, and the Navajo and Coconino Sandstones, Grand Canyon − Flood Geology Disproved

62. Origin of Horseshoe Bend, Arizona, and the Navajo and Coconino Sandstones, Grand Canyon − Flood Geology Disproved Lorence G. Collins July 1, 2020 Email address: [email protected] Abstract Young-Earth creationists (YEC) claim that Horseshoe Bend in Arizona was carved by the Colorado River soon after Noah's Flood had deposited sedimentary rocks during the year of the Flood about 4,400 years ago. Its receding waters are what entrenched the Colorado River in a U-shaped horseshoe bend. Conventional geology suggests that the Colorado River was once a former meandering river flowing on a broad floodplain, and as tectonic uplift pushed up northern Arizona, the river slowly cut down through the sediments while still preserving its U-shaped bend. Both the Jurassic Navajo Sandstone at Horseshoe Bend, and the underlying Permian Coconino Sandstone exposed in the Grand Canyon, are claimed by YECs to be deposited by Noah's Flood while producing underwater, giant, cross-bedded dunes. Conventional geology interprets that these cross-bedded dunes were formed in a desert environment by blowing wind. Evidence is presented in this article to show examples of features that cannot be explained by the creationists' Flood geology model. Introduction The purpose of this article is two-fold. The first is to demonstrate that the physical features of the Navajo and Coconino sandstones at Horseshoe Bend and in the Grand Canyon National Park are best understood by contemporary geology as aeolian sand dunes deposited by blowing wind. The second is to describe how Horseshoe Bend and the Grand Canyon were formed by the Colorado River slowly meandering across a flat floodplain and eroding the Bend and the Canyon over a few million years as plate tectonic forces deep in the earth’s crust uplifted northern Arizona and southern Utah. -

Walking Guide

Grand Canyon National Park Trail of Time National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Walking Guide Find these markers and find these views along the 2 km (1.2 mile) timeline trail. Each one represents a key time in this region’s geologic history. Yavapai Observation Station and the Park geology brochure have additional information about all the Grand Canyon rock layers. Canyon Carving last 6 million years Colorado River Find the Colorado River deep in the canyon. This mighty river has carved the Grand Canyon in “only” the last six million years. Upper Flat Layers 270–315 million years old Kaibab (KIE-bab) Formation Toroweap (TORO-weep) Formation Coconino (coco-KNEE-no) Sandstone Hermit Formation Supai (SOO-pie) Group You are standing on the top rock layer, called the Kaibab Formation. It was deposited 270 million years ago in a shallow sea. From this point you can see lower (older) layers too. The Trail of Time is a joint project of Grand Canyon National Park, the University of New Mexico, and the National Science Foundation Grand Canyon National Park Trail of Time National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Walking Guide Lowest Flat Layer younger layers above 525 million years old older layers below Tapeats (ta-PEETS) Sandstone Your best view of the Tapeats Sandstone is from marker 590. But it is actually 525 million years old. It is the oldest of the horizontal rock layers, but not the oldest rock in the canyon. Supergroup 742–1,255 million years old Hakatai (HACK-a-tie) Shale Find the bright orange Hakatai Shale. -

Grand Canyon Provenance for Orthoquartzite Clasts in the Lower Miocene of Coastal Southern California GEOSPHERE

Research Paper GEOSPHERE Grand Canyon provenance for orthoquartzite clasts in the lower Miocene of coastal southern California 1 1 2 3 4 1 GEOSPHERE, v. 15, no. X Leah Sabbeth , Brian P. Wernicke , Timothy D. Raub , Jeffery A. Grover , E. Bruce Lander , and Joseph L. Kirschvink 1Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology, 1200 E. California Boulevard, MC 100-23, Pasadena, California 91125, USA 2School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of St. Andrews, St. Andrews, Scotland, UK KY16 9AJ https://doi.org/10.1130/GES02111.1 3Department of Physical Sciences, Cuesta College, San Luis Obispo, California 93403-8106, USA 4Paleo Environmental Associates, Inc., Altadena, California 91101-3205, USA 14 figures; 6 tables; 2 sets of supplemental files CORRESPONDENCE: [email protected] ABSTRACT sandstones. Collectively, these data define a mid-Tertiary, SW-flowing “Arizona River” drainage system between the rapidly eroding eastern Grand Canyon CITATION: Sabbeth, L., Wernicke, B.P., Raub, T.D., Grover, J.A., Lander, E.B., and Kirschvink, J.L., Orthoquartzite detrital source regions in the Cordilleran interior yield region and coastal California. 2019, Grand Canyon provenance for orthoquartzite clast populations with distinct spectra of paleomagnetic inclinations and clasts in the lower Miocene of coastal southern Cal- detrital zircon ages that can be used to trace the provenance of gravels ifornia: Geosphere, v. 15, no. X, p. 1–26, https://doi. org/10.1130/GES02111.1. deposited along the western margin of the Cordilleran orogen. An inventory ■ INTRODUCTION of characteristic remnant magnetizations (CRMs) from >700 sample cores Science Editor: Andrea Hampel from orthoquartzite source regions defines a low-inclination population of Among the most difficult problems in geology is constraining the kilome- Associate Editor: James A. -

Cenozoic Stratigraphy and Paleogeography of the Grand Canyon, AZ Amanda D'el

Pre-Cenozoic Stratigraphy and Paleogeography of the Grand Canyon, AZ Amanda D’Elia Abstract The Grand Canyon is a geologic wonder offering a unique glimpse into the early geologic history of the North American continent. The rock record exposed in the massive canyon walls reveals a complex history spanning more than a Billion years of Earth’s history. The earliest known rocks of the Southwestern United States are found in the Basement of the Grand Canyon and date Back to 1.84 Billion years old (Ga). The rocks of the Canyon can Be grouped into three distinct sets Based on their petrology and age (Figure 1). The oldest rocks are the Vishnu Basement rocks exposed at the Base of the canyon and in the granite gorges. These rocks provide a unique clue as to the early continental formation of North America in the early PrecamBrian. The next set is the Grand Canyon Supergroup, which is not well exposed throughout the canyon, But offers a glimpse into the early Beginnings of Before the CamBrian explosion. The final group is the Paleozoic strata that make up the Bulk of the Canyon walls. Exposure of this strata provides a detailed glimpse into North American environmental changes over nearly 300 million years (Ma) of geologic history. Together these rocks serve not only as an awe inspiring Beauty But a unique opportunity to glimpse into the past. Vishnu Basement Rocks The oldest rocks exposed within the Grand Canyon represent some of the earliest known rocks in the American southwest. John Figure 1. Stratigraphic column showing Wesley Paul referred to them as the “dreaded the three sets of rocks found in the Grand rock” Because they make up the walls of some Canyon, their thickness and approximate of the quickest and most difficult rapids to ages (Mathis and Bowman, 2006).