The Supreme Court 2018‐2019 Topic Proposal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Military Tribunals: the Quirin Precedent

Order Code RL31340 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Military Tribunals: The Quirin Precedent March 26, 2002 Louis Fisher Senior Specialist in Separation of Powers Government and Finance Division Congressional Research Service The Library of Congress Military Tribunals: The Quirin Precedent Summary On November 13, 2001, President George W. Bush issued a military order to provide for the detention, treatment, and trial of those who assisted the terrorist attacks on the two World Trade Center buildings in New York City and the Pentagon on September 11. In creating a military commission (tribunal) to try the terrorists, President Bush modeled his tribunal in large part on a proclamation and military order issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1942, after the capture of eight German saboteurs. This report describes the procedures used by the World War II military tribunal to try the eight Germans, the habeas corpus petition to the Supreme Court, and the resulting convictions and executions. Why was the tribunal created, and why were its deliberations kept secret? How have scholars evaluated the Court’s decision in Ex parte Quirin (1942)? The decision was unanimous, but archival records reveal division and disagreement among the Justices. Also covered in this report is a second effort by Germany two years later to send saboteurs to the United States. The two men captured in this operation were tried by a military tribunal, but under conditions and procedures that substantially reduced the roles of the President and the Attorney General. Those changes resulted from disputes within the Administration, especially between the War Department and the Justice Department. -

Ex Parte Quirin", the Nazi Saboteur Case Andrew Kent

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 66 | Issue 1 Article 3 1-2013 Judicial Review for Enemy Fighters: The ourC t's Fateful Turn in "Ex parte Quirin", the Nazi Saboteur Case Andrew Kent Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Andrew Kent, Judicial Review for Enemy Fighters: The ourC t's Fateful Turn in "Ex parte Quirin", the Nazi Saboteur Case, 66 Vanderbilt Law Review 150 (2019) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol66/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Judicial Review for Enemy Fighters: The Court's Fateful Turn in Exparte Quirin, the Nazi Saboteur Case Andrew Kent 66 Vand. L. Rev. 153 (2013) The last decade has seen intense disputes about whether alleged terrorists captured during the nontraditional post- 9/11 conflict with al Qaeda and affiliated groups may use habeas corpus to challenge their military detention or military trials. It is time to take a step back from 9/11 and begin to evaluate the enemy combatant legal regime on a broader, more systemic basis, and to understand its application to future conflicts. A leading precedent ripe for reconsideration is Ex parte Quirin, a World War II-era case in which the Supreme Court held that saboteurs admittedly employed by an enemy nation's military had a right to access civilian courts during wartime to challenge their trial before a military commission. -

Stacking the Deck Against Suspected Terrorists

Stacking the Deck against Suspected Terrorists: The Dwindling Procedural Limits on the Government's Power to Indefinitely Detain United States Citizens as Enemy Combatants Nickolas A. Kacprowski* I. INTRODUCTION Jose Padilla is an American citizen.' The United States govern- ment took Padilla into custody on American soil in May 2002, and it has classified him as an enemy combatant, asserting that it can detain him indefinitely without charging him with any crime.2 Yaser Hamdi is also an American citizen who has been detained since Fall 2001, has been classified as an enemy combatant, and has yet to be charged with a crime.3 In Padilla v. Bush4, the District Court for the Southern Dis- trict of New York, like the Hamdi court, decided that because of the present war on terrorism, the government had the authority to classify citizens as enemy combatants. However, unlike the Hamdi court, the Padilla court ruled that, despite the government's classification of Padilla as an enemy combatant, he should be given access to an attor- ney in the prosecution of his habeas corpus petition and that the court would then review the charges and evidence and decide whether the government properly classified Padilla as an enemy combatant.5 Both the Padilla6 and the Hamdi7 courts applied a Supreme Court case from J.D. Candidate 2004, Northwestern University; B.A. Northwestern University, 2001. The author would like to thank his parents, Greg and Diane Kacprowski for a lifetime of love and support. The author recognizes two colleagues and friends at Northwestern, Len Conapinski and David Johanson, for their help with this Note. -

Amicus Brief by Quirin Historians

No. 08-368 ================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- ALI SALEH KAHLAH AL-MARRI, Petitioner, v. DANIEL SPAGONE, United States Navy Commander, Consolidated Naval Brig, Respondent. --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- On Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Fourth Circuit --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- BRIEF OF HISTORIANS AND SCHOLARS OF EX PARTE QUIRIN AS AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- JONATHAN M. FREIMAN KENNETH D. HEATH Of Counsel ALISON M. WEIR NATIONAL LITIGATION PROJECT WIGGIN AND DANA LLP OF THE ALLARD K. One Century Tower LOWENSTEIN CLINIC P.O. Box 1832 YALE LAW SCHOOL New Haven, CT 06508-1832 127 Wall Street (203) 498-4400 New Haven, CT 06511 (203) 498-4584 ================================================================ COCKLE LAW BRIEF PRINTING CO. (800) 225-6964 OR CALL COLLECT (402) 342-2831 i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTERESTS OF AMICI CURIAE ......................... 1 SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT ....................... 4 ARGUMENT........................................................... 5 I. The Historical Circumstances Surrounding Quirin........................................................... 5 A. Background: the covert invasion, cap- ture and military commission trial....... 5 B. The Legal Challenge: habeas petitions, -

US Citizens As Enemy Combatants

Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development Volume 18 Issue 2 Volume 18, Spring 2004, Issue 2 Article 14 U.S. Citizens as Enemy Combatants: Indication of a Roll-Back of Civil Liberties or a Sign of our Jurisprudential Evolution? Joseph Kubler Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/jcred This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. U.S. CITIZENS AS ENEMY COMBATANTS; INDICATION OF A ROLL-BACK OF CIVIL LIBERTIES OR A SIGN OF OUR JURISPRUDENTIAL EVOLUTION? JOSEPH KUBLER I. EXTRAORDINARY TIMES Exigent circumstances require our government to cross legal boundaries beyond those that are unacceptable during normal times. 1 Chief Justice Rehnquist has expressed the view that "[w]hen America is at war.., people have to get used to having less freedom."2 A tearful Justice Sandra Day O'Connor reinforced this view, a day after visiting Ground Zero, by saying that "we're likely to experience more restrictions on our personal freedom than has ever been the case in our country."3 However, extraordinary times can not eradicate our civil liberties despite their call for extraordinary measures. "Lawyers have a special duty to work to maintain the rule of law in the face of terrorism, Justice O'Connor said, adding in a quotation from Margaret 1 See Christopher Dunn & Donna Leiberman, Security v. -

The Influence of Ex-Parte Quirin and Courts

Copyright 2008 by Northwestern University School of Law Vol. 103 Northwestern University Law Review Colloquy THE INFLUENCE OF EX PARTE QUIRIN AND COURTS-MARTIAL ON MILITARY COMMISSIONS Morris D. Davis* Professor Greg McNeal was an academic consultant to the prosecution during my tenure as the Chief Prosecutor for the military commissions at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. We had similar perspectives on many issues, and we still confer on detainee matters. I concur with the views expressed in his essay.1 I write to address two issues Professor McNeal identified and com- ment on how they affect the military commissions. First, I examine the case of the Nazi saboteurs—captured, tried, and executed in the span of seven weeks in 1942—and its influence on the decision in 2001 to resurrect military commissions. Second, I assess the conflicting statutory provisions in the Military Commissions Act and the impact on full, fair, and open tri- als. I. ATTEMPTING TO REPEAT HISTORY Professor McNeal argues that the administration chose military com- missions to protect information collected for intelligence (intel) purposes from disclosure. Safeguarding intel, particularly the sources and methods used to acquire information, was a key factor, but I believe the decision had a broader basis heavily influenced by a precedent-setting trial in 1942 that became the template for the President‘s Military Order of November 13, 2001.2 Shortly after midnight the morning of June 13, 1942, four men left a German submarine and came ashore at Amagansett Beach, New York.3 * Morris D. Davis served as Chief Prosecutor for the military commissions at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, from September 2005 to October 2007. -

Tiersma I- Legal Language

THE NATURE OF LEGAL LANGUAGE [This material may be used for educational or academic purposes if cited or referred to as: Peter Tiersma, The Nature of Legal Language, http://www.languageandlaw.org/NATURE.HTM] One of the great paradoxes about the legal profession is that lawyers are, on the one hand, among the most eloquent users of the English language while, on the other, they are perhaps its most notorious abusers. Why is it that lawyers, who may excel in communicating with a jury, seem incapable of writing an ordinary, comprehensible English sentence in a contract, deed, or will? And what can we do about it? Consider, first, the eloquence of the legal profession. Daniel Webster was famed for his oratory skills. Called upon to assist the prosecution in a murder case, Webster addressed any hesitations the jurors might have harbored about their power to punish the guilty. In doing so, he provided a memorable defense of the theory of deterrence: The criminal law is not founded in a principle of vengeance. It does not punish that it may inflict suffering. The humanity of the law feels and regrets every pain that it causes, every hour of restraint it imposes, and more deeply still, every life it forfeits. But it uses evil, as the means of preventing greater evil. It seeks to deter from crime, by the example of punishment. This is its true, and only true main object. It restrains the liberty of the few offenders, that the many who do not offend, may enjoy their own liberty. It forfeits the life of the murderer, that other murders may not be committed. -

Operation Pastorius WWII

Operation Pastorius WWII Shortly after Adolf Hitler declared war on the United States, just four days after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, he was eager to prove to the United States that it was vulnerable despite its distance from Europe, Hitler ordered a sabotage operation to be mounted against targets inside America. The task fell to the Abwehr (defense) section of the German Military Intelligence Corps headed by Admiral Wilhelm Canaris. The job was right up the Abwehr’s alley. It already had conducted extensive sabotage operations against the Reich‘s European enemies, developing all the necessary tools and techniques and establishing an elaborate sabotage school in the wooded German countryside near Brandenburg. Lieutenant Walter Kappe, 37, a pudgy, bull-necked man, was given command of the mission against America, which he dubbed Operation Pastorius, after an early German settler in America. Kappe was a longtime member of the Nazi party, and he also knew the United States very well, having lived there for 12 years. To find men suitable for his enterprise, Lieutenant Kappe scoured the records of the Ausland Institute, which had financed thousands of German expatriates’ return from America. Kappe selected 12 whom he thought were energetic, capable and loyal to the German cause. Most were blue-collar workers, and all but two had long been members of the party. Four dropped out of the team almost immediately; the rest were organized into two teams of four. George John Dasch, the eldest at 39, was chosen to lead the first team. He was a glib talker with what Kappe thought were American mannerisms. -

Secret Operations of World War II. by Alexander Stillwell. London, United Kingdom: Amber Books Ltd, 2018

Journal of Strategic Security Volume 11 Number 4 Article 6 Secret Operations of World War II. By Alexander Stillwell. London, United Kingdom: Amber Books Ltd, 2018. Millard E. Moon U.S. Air Force Office of Special Investigations Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss pp. 89-93 Recommended Citation Moon, Millard E.. "Secret Operations of World War II. By Alexander Stillwell. London, United Kingdom: Amber Books Ltd, 2018.." Journal of Strategic Security 11, no. 4 (2019) : 89-93. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.11.4.1717 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss/vol11/iss4/6 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Strategic Security by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Secret Operations of World War II. By Alexander Stillwell. London, United Kingdom: Amber Books Ltd, 2018. This book review is available in Journal of Strategic Security: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss/ vol11/iss4/6 Moon: Book Review: <i>Secret Operations of World War II</i> Secret Operations of World War II. By Alexander Stillwell. London, United Kingdom: Amber Books Ltd, 2018. ISBN 978-1- 78274-632-4. Photographs. Bibliography. Index. Pp. 224. $21.77. The author has done an excellent job of providing an overview of the most prominent secret operations, and the exploits of some of the most heroic, but little known, agents operating for the Allied forces in World War II. -

The Proceedings of GREAT Day 2020

Proceedings of GREAT Day Volume 2020 Article 24 2021 The Proceedings of GREAT Day 2020 Follow this and additional works at: https://knightscholar.geneseo.edu/proceedings-of-great-day Recommended Citation (2021) "The Proceedings of GREAT Day 2020," Proceedings of GREAT Day: Vol. 2020 , Article 24. Available at: https://knightscholar.geneseo.edu/proceedings-of-great-day/vol2020/iss1/24 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the GREAT Day at KnightScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Proceedings of GREAT Day by an authorized editor of KnightScholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. et al.: <i>The Proceedings of GREAT Day</i> 2020 The Proceedings of GREAT Day 2020 SUNY Geneseo Geneseo, NY Published by KnightScholar, 2021 1 Proceedings of GREAT Day, Vol. 2020 [2021], Art. 24 © 2021 The State University of New York at Geneseo This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License unless otherwise noted. To view a copy of this license, visit http://crea- tivecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Milne Library 1 College Circle Geneseo, NY 14454 GREAT Day logos have been used with the permission of their original designer, Dr. Stephen West. ISBN: 978-1-942341-78-9 https://knightscholar.geneseo.edu/proceedings-of-great-day/vol2020/iss1/24 2 et al.: <i>The Proceedings of GREAT Day</i> 2020 About GREAT Day and The Proceedings of GREAT Day Geneseo Recognizing Excellence, Achievement, & Talent is a college-wide sympo- sium celebrating the creative and scholarly endeavors of our students. In addition to recognizing the achievements of our students, the purpose of GREAT Day is to help foster academic excellence, encourage professional development, and build connec- tions within the community. -

CONGRESS! on AL RECORD-HOUSE DECEMBER 14 Sylvan S

6.06 CONGRESS! ON AL RECORD-HOUSE DECEMBER 14 Sylvan S. McCrary to be postmaster at Joaquin, Tex., in John L. Augustine, Lordsburg. place of S. S. McCrary. Incumbent's eommission ,. '()ired De Charles E. Anderson, Roy. cember 10, 1928; Louise N. Martin, SocoiTo. William I. Witherspoon to be postmaster at McAllen, Tex., in OHIO place of W. I. Witherspoon. Incumbent's commission expired December 10, 1928. _ George P. Foresman, Circleville. Charles A. Reiter to be postmaster at Muenster, Tex., in place Alsina E. Andrews, Risingsun. Horace G. Randall, Sylvania. of 0. A. Reiter. Incumbent's commission expired D~ember 10, 1928. OKLAHOMA Charles I. Sneclecor to be postmaster at Needville, Tex., in Henry A. Ravia, Bessie. place of C. I. Snedecor. Incumbent's commission expired De Burton A. Tyrrell, Fargo. cember 10, 1928. Earl C. Moore, Forgan. Lydia Teller to be postmaster at Orange Grove, Tex., in place Benjamin F. R!irick, Guymon. of Lydia Teller. Incumbent's commission e1..--pired December 10, Helen Whitlock, Mru:amec. 1928. SOUTH CAROLINA Casimiro P. Alvarez to be postmaster at Riogrande, Tex., in John W. Willis, Lynchburg. place of C. P. Alvarez. Ineumbent'.s commission expired Decem- ber 10, 1928. · WEST VIRGINIA George 1\f. Sewell to be postmaster at Talpa, Tex., in place of Mary .Allen, Filbert. G. M. Sewell. Incumbent's commission expil·ed December 10, Minnie Ratliff, Yukon. 1928.-· Charles If''. Boettcher to be postmaster at Weimar, Tex., in WITHDRAWAL place of C. F. Boettcher. Incumbent's commission expired De cember 10, 1928. Exeuutive nominatio-n witlzarawn trorn the Senate Decembf:»' -14 (legislative da·y of D ecem-ber 13), 1928 UTAH POSTMASTER Carlos C. -

M Master R Proje Ect Bib Bliogr Raphy

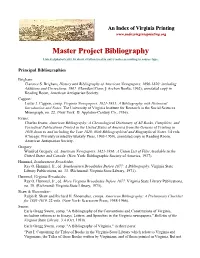

An Index of Virginia Printing www.indexvirginiaprinting.org Master Project Bibliography Listed alphabetically by short citation used in entrry notes according to source type. Principal Bibliographies Brigham: Clarence S. Brigham, History and Bibliography of American Newsppapers, 16900-1820: including Additions and Corrections, 1961. (Hamden [Conn.]: Archon Books, 1962); annotated copy in Reading Room, American Antiquarian Society. Cappon: Lester J. Cappon, comp. Virginia Newspapers, 1821-1935: A Biblioggraphy with Historical Introduction and Notes. The University of Virginia Institute for Research in the Social Sciences Monograph, no. 22. (New York: D. Appleton-Century Co., 1936). Evans: Charles Evans, American Bibliography: A Chronological Dictionary of All Books, Pamphlets, and Periodical Publications Printed in the United States of America from the Genesis of Printing in 1639 down to and including the Year 1820: With Bibliographical and Biographical Notes. 14 vols. (Chicago: Privately printed by Blakely Press, 1903-1959), annotated copy in Reading Room, American Antiquarian Society. Gregory: Winifred Gregory, ed. American Newspapers, 1821-1936: A Union List of Files Available in the United States and Canada. (New York: Bibliographic Society of America, 1937). Hummel, Southeastern Broadsides. Ray O. Hummel, Jr., ed. Southeastern Broadsides Before 1877: A Bibliography. Virginia State Library Publications, no. 33. (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1971). Hummel, Virginia Broadsides. Ray O. Hummel, Jr., ed. More ViV rginia Broadsides Beforre 1877. Virginia State Library Publications, no. 39. (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1975). Shaw & Shoemaker: Ralph R. Shaw and Richard H. Shoemaker, comps. American Bibliography: A Preliminary Checklist for 1801-1819. 22 vols. (New York: Scarecrow Press, 1958-1966). Swem: Earle Gregg Swem, comp.