Operation Pastorius WWII

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Military Tribunals: the Quirin Precedent

Order Code RL31340 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Military Tribunals: The Quirin Precedent March 26, 2002 Louis Fisher Senior Specialist in Separation of Powers Government and Finance Division Congressional Research Service The Library of Congress Military Tribunals: The Quirin Precedent Summary On November 13, 2001, President George W. Bush issued a military order to provide for the detention, treatment, and trial of those who assisted the terrorist attacks on the two World Trade Center buildings in New York City and the Pentagon on September 11. In creating a military commission (tribunal) to try the terrorists, President Bush modeled his tribunal in large part on a proclamation and military order issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1942, after the capture of eight German saboteurs. This report describes the procedures used by the World War II military tribunal to try the eight Germans, the habeas corpus petition to the Supreme Court, and the resulting convictions and executions. Why was the tribunal created, and why were its deliberations kept secret? How have scholars evaluated the Court’s decision in Ex parte Quirin (1942)? The decision was unanimous, but archival records reveal division and disagreement among the Justices. Also covered in this report is a second effort by Germany two years later to send saboteurs to the United States. The two men captured in this operation were tried by a military tribunal, but under conditions and procedures that substantially reduced the roles of the President and the Attorney General. Those changes resulted from disputes within the Administration, especially between the War Department and the Justice Department. -

Combat Casualty Care and Lessons Learned from the Last 100 Years of War

Author’s Accepted Manuscript Combat Casualty Care and Lessons Learned from the Last 100 Years of War Matthew Bradley, Matthew Nealiegh, John Oh, Philip Rothberg, Eric Elster, Norman Rich www.elsevier.com/locate/cpsurg PII: S0011-3840(16)30157-5 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1067/j.cpsurg.2017.02.004 Reference: YMSG552 To appear in: Current Problems in Surgery Cite this article as: Matthew Bradley, Matthew Nealiegh, John Oh, Philip Rothberg, Eric Elster and Norman Rich, Combat Casualty Care and Lessons Learned from the Last 100 Years of War, Current Problems in Surgery, http://dx.doi.org/10.1067/j.cpsurg.2017.02.004 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting galley proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. COMBAT CASUALTY CARE AND LESSONS LEARNED FROM THE LAST 100 YEARS OF WAR Matthew Bradley, M.D. 1, 2, Matthew Nealiegh, M.D. 1, John Oh, M.D. 1, Philip Rothberg, M.D. 1, Eric Elster M.D. 1, 2, Norman Rich M.D. 1 1 Department of Surgery, Uniformed Services University -Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, 8901 Wisconsin Ave., Bethesda, MD 20889 2Naval Medical Research Center, 503 Robert Grant Ave., Silver Spring, MD 20910 Corresponding Author: Matthew J. -

A Counterintelligence Reader, Volume 2 Chapter 1, CI in World

CI in World War II 113 CHAPTER 1 Counterintelligence In World War II Introduction President Franklin Roosevelts confidential directive, issued on 26 June 1939, established lines of responsibility for domestic counterintelligence, but failed to clearly define areas of accountability for overseas counterintelligence operations" The pressing need for a decision in this field grew more evident in the early months of 1940" This resulted in consultations between the President, FBI Director J" Edgar Hoover, Director of Army Intelligence Sherman Miles, Director of Naval Intelligence Rear Admiral W"S" Anderson, and Assistant Secretary of State Adolf A" Berle" Following these discussions, Berle issued a report, which expressed the Presidents wish that the FBI assume the responsibility for foreign intelligence matters in the Western Hemisphere, with the existing military and naval intelligence branches covering the rest of the world as the necessity arose" With this decision of authority, the three agencies worked out the details of an agreement, which, roughly, charged the Navy with the responsibility for intelligence coverage in the Pacific" The Army was entrusted with the coverage in Europe, Africa, and the Canal Zone" The FBI was given the responsibility for the Western Hemisphere, including Canada and Central and South America, except Panama" The meetings in this formative period led to a proposal for the organization within the FBI of a Special Intelligence Service (SIS) for overseas operations" Agreement was reached that the SIS would act -

Tsetusuo Wakabayashi, Revealed

Tsetusuo Wakabayashi, Revealed By Dwight R. Rider Edited by Eric DeLaBarre Preface Most great works of art begin with an objective in mind; this is not one of them. What follows in the pages below had its genesis in a research effort to determine what, if anything the Japanese General Staff knew of the Manhattan Project and the threat of atomic weapons, in the years before the detonation of an atomic bomb over Hiroshima in August 1945. That project drew out of an intense research effort into Japan’s weapons of mass destruction programs stretching back more than two decades; a project that remains on-going. Unlike a work of art, this paper is actually the result of an epiphany; a sudden realization that allows a problem, in this case the Japanese atomic energy and weapons program of World War II, to be understood from a different perspective. There is nothing in this paper that is not readily accessible to the general public; no access to secret documents, unreported interviews or hidden diaries only recently discovered. The information used in this paper has been, for the most part, available to researchers for nearly 30 years but only rarely reviewed. The paper that follows is simply a narrative of a realization drawn from intense research into the subject. The discoveries revealed herein are the consequence of a closer reading of that information. Other papers will follow. In October of 1946, a young journalist only recently discharged from the US Army in the drawdown following World War II, wrote an article for the Atlanta Constitution, the premier newspaper of the American south. -

Rioting and Time

Rioting and time Collective violence in Manchester, Liverpool and Glasgow, 1800-1939 A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2018 Matteo Tiratelli School of Social Sciences 1 Table of contents Abstract 4 Declaration & Copyright 5 Acknowledgements 6 Chapter 1 — Rioting and time 7 Chapter 2 — Don’t call it a riot 24 Chapter 3 — Finding riots and describing them 42 Chapter 4 — Riots in space, time and society 64 Chapter 5 — The changing practice of rioting 102 Chapter 6 — The career of a riot: triggers and causes 132 Chapter 7 — How do riots sustain themselves? 155 Chapter 8 — Riots: the past and the future 177 Bibliography 187 Appendix 215 Word count: 70,193 2 List of tables Table 1: The spaces where riots started 69 Table 2: The places where riots started 70 Table 3: The number of riots happening during normal working hours 73 Table 4: The number of riots which happen during particular calendrical events 73 Table 5: The proportion of non-industrial riots by day of the week 75 Table 6: The likelihood of a given non-industrial riot being on a certain day of the week 75 Table 7: The likelihood of a given riot outside of Glasgow involving prison rescues 98 Table 8: The likelihood of a given riot involving begging or factory visits 111 Table 9: The likelihood of a given riot targeting specific individuals or people in their homes 119 List of figures Figure 1: Angelus Novus (1920) by Paul Klee 16 Figure 2: Geographic spread of rioting in Liverpool 67 Figure 3: Geographic spread of rioting in Manchester 68 Figure 4: Geographic spread of rioting in Glasgow 68 Figure 5: The number of riots per year 78 Figure 6: The number of riots involving prison rescues per year 98 3 Abstract The 19th century is seen by many as a crucial turning point in the history of protest in Britain and across the global north. -

And the Congress Shall Have Power To

AND THE CONGRESS SHALL HAVE POWER TO . : THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE D.C. CIRCUIT COURT’S PER CURIAM DECISION IN BAHLUL V. UNITED STATES Clarke D. Cotton* I. INTRODUCTION Today, Amagansett, New York Is an attractIve East Hampton neighborhood.1 A get-away for the rich and powerful, there are typically more vacatIoners than resIdents In the town at any gIven tIme.2 Among the many mansions that populate Amagansett is a historic Coast Guard station that sits just off Atlantic Avenue beach.3 In 1966 the station was moved to a prIvate resIdence to protect and preserve Its features.4 In 2007, the station was moved back to its original spot off Atlantic Avenue beach and, now, is protected as a historical landmark.5 This Is the station that Coast Guardsman John C. Cullen sprInted to In 1942 to warn of a most extraordinary finding: a group of Nazis had landed on AmerIcan soil with explosives in hand, they were here to do our country harm.6 Thirty-five miles outside of Berlin, Germany, laid a camp in which eight Nazi soldiers were trained in the use of explosives, fuses, and detonators.7 These men received their InstructIon from Lt. Walter Kappe and focused on destroying railroads, factories, and other strategic U.S. milItary and Infrastructure targets.8 The eight soldiers were divided into two groups. The first was led by Edward John Kerling, and included Werner ThIel, Hermann Neubauer, and Herbert Hans Haupt.9 Kerling’s * AssocIate Member, 2016-2017, University of Cincinnati Law Review 1. John Rather, If You’re Thinking of Living in Amagansett, L.I.; A Down to Earth Hamptons Alternative, N.Y. -

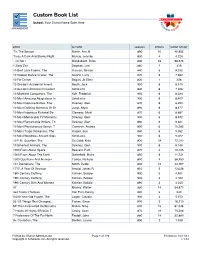

Custom Book List

Custom Book List School: Your District Name Goes Here MANAGEMENT BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® POINTS WORD COUNT 'Tis The Season Martin, Ann M. 890 10 40,955 'Twas A Dark And Stormy Night Murray, Jennifer 830 4 4,224 ...Or Not? Mandabach, Brian 840 23 98,676 1 Zany Zoo Degman, Lori 860 1 415 10 Best Love Poems, The Hanson, Sharon 840 6 8,332 10 Coolest Dance Crazes, The Swartz, Larry 870 6 7,660 10 For Dinner Bogart, Jo Ellen 820 1 328 10 Greatest Accidental Inventi Booth, Jack 900 6 8,449 10 Greatest American President Scholastic 840 6 7,306 10 Mightiest Conquerors, The Koh, Frederick 900 6 8,034 10 Most Amazing Adaptations In Scholastic 900 6 8,409 10 Most Decisive Battles, The Downey, Glen 870 6 8,293 10 Most Defining Moments Of Th Junyk, Myra 890 6 8,477 10 Most Ingenious Fictional De Clemens, Micki 870 6 8,687 10 Most Memorable TV Moments, Downey, Glen 900 6 8,912 10 Most Remarkable Writers, Th Downey, Glen 860 6 9,321 10 Most Revolutionary Songs, T Cameron, Andrea 890 6 10,282 10 Most Tragic Romances, The Harper, Sue 860 6 9,052 10 Most Wondrous Ancient Sites Scholastic 900 6 9,022 10 P.M. Question, The De Goldi, Kate 830 18 72,103 10 Smartest Animals, The Downey, Glen 900 6 8,148 1000 Facts About Space Beasant, Pam 870 4 10,145 1000 Facts About The Earth Butterfield, Moira 850 6 11,721 1000 Questions And Answers Tames, Richard 890 9 38,950 101 Dalmatians, The Smith, Dodie 830 12 44,767 1777: A Year Of Decision Arnold, James R. -

Secret Operations of World War II. by Alexander Stillwell. London, United Kingdom: Amber Books Ltd, 2018

Journal of Strategic Security Volume 11 Number 4 Article 6 Secret Operations of World War II. By Alexander Stillwell. London, United Kingdom: Amber Books Ltd, 2018. Millard E. Moon U.S. Air Force Office of Special Investigations Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss pp. 89-93 Recommended Citation Moon, Millard E.. "Secret Operations of World War II. By Alexander Stillwell. London, United Kingdom: Amber Books Ltd, 2018.." Journal of Strategic Security 11, no. 4 (2019) : 89-93. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.11.4.1717 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss/vol11/iss4/6 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Strategic Security by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Secret Operations of World War II. By Alexander Stillwell. London, United Kingdom: Amber Books Ltd, 2018. This book review is available in Journal of Strategic Security: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss/ vol11/iss4/6 Moon: Book Review: <i>Secret Operations of World War II</i> Secret Operations of World War II. By Alexander Stillwell. London, United Kingdom: Amber Books Ltd, 2018. ISBN 978-1- 78274-632-4. Photographs. Bibliography. Index. Pp. 224. $21.77. The author has done an excellent job of providing an overview of the most prominent secret operations, and the exploits of some of the most heroic, but little known, agents operating for the Allied forces in World War II. -

Ex Parte Quirin, 317 U.S. 1 (1942) 63 S.Ct

Todd, Jonathan 1/22/2014 For Educational Use Only Ex parte Quirin, 317 U.S. 1 (1942) 63 S.Ct. 2, 87 L.Ed. 3 Attorneys and Law Firms 63 S.Ct. 2 Supreme Court of the United States **6 *6 Colonel Kenneth C. Royall, A.U.S., of Raleigh, N.C., for petitioners. Ex parte QUIRIN. Ex parte HAUPT. *11 Mr. Francis Biddle, Atty. Gen., for respondent. Ex parte KERLING. Opinion Ex parte BURGER. Ex parte HEINCK. *18 Mr. Chief Justice STONE delivered the opinion of the Ex parte THIEL. Court. Ex parte NEUBAUER. These cases are brought here by petitioners' several UNITED STATES ex rel. QUIRIN applications for leave to file petitions for habeas corpus in this v. Court, and by their petitions for certiorari to review orders of COX, Brig. Gen., U.S.A., Provost Marshal of the the District Court for the District of Columbia, which denied Military District of Washington, and 6 other cases. their applications for leave to file petitions for habeas corpus in that court. Nos. -- Original and Nos. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7-July Special Term, 1942. | Argued July The question for decision is whether the detention of 29, 30, 1942. | Decided July 31, 1942. petitioners by respondent for trial by Military Commission, | Extended opinion filed Oct. 29, 1942. appointed by Order of the President of July 2, 1942, *19 on charges preferred against them purporting to set out their Motions for leave to file petitions for writs of habeas corpus. violations of the law of war and of the Articles of War, is in conformity to the laws and Constitution of the United States. -

Erich Gimpel and Colepaugh Case KV 2/564

Reference abstracts of KV 2/564 This document contains materials derived from the latter file Its purpose: to be used as a kind of reference document, containing my personal selection of report sections; considered being of relevance. My input: I have in almost every case created transcripts of the just reproduced file content. However, sometimes adding my personal opinion; always accompanied by: AOB (with- or without brackets) Please do not multiply this document Remember: that the section-copies still do obey to Crown Copyright By Arthur O. Bauer Please notice: For simplicity, I have this time not completely transcribed all genuine text contents, therefore I would like to advise you to read these passages also. This concerns a unique Story, where two spies had been brought ashore on the beach of Frenchman’s Bay in the US State Maine, on 29th November 1944. One was Erich Gimpel the second one was Colepaugh a US born ‘subject’. Erich Gimpel passed finally away in 2010, living Sao Paulo, at an age of 100 years! As to ease to understand the context I first would like to quote from Wikipedia. Quoting from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erich_Gimpel Erich Gimpel From Wikipedia, the free encyclopaedia Erich Gimpel (25 March 1910 in Merseburg – 3 September 2010 in Sao Paulo) was a German spy during World War II. Together with William Colepaugh, he traveled to the United States on an espionage mission (operation Elster) in 1944 and was subsequently captured by the FBI in New York City.[1] German secret agent Gimpel had been a radio operator for mining companies in Peru in the 1930s. -

CONGRESS! on AL RECORD-HOUSE DECEMBER 14 Sylvan S

6.06 CONGRESS! ON AL RECORD-HOUSE DECEMBER 14 Sylvan S. McCrary to be postmaster at Joaquin, Tex., in John L. Augustine, Lordsburg. place of S. S. McCrary. Incumbent's eommission ,. '()ired De Charles E. Anderson, Roy. cember 10, 1928; Louise N. Martin, SocoiTo. William I. Witherspoon to be postmaster at McAllen, Tex., in OHIO place of W. I. Witherspoon. Incumbent's commission expired December 10, 1928. _ George P. Foresman, Circleville. Charles A. Reiter to be postmaster at Muenster, Tex., in place Alsina E. Andrews, Risingsun. Horace G. Randall, Sylvania. of 0. A. Reiter. Incumbent's commission expired D~ember 10, 1928. OKLAHOMA Charles I. Sneclecor to be postmaster at Needville, Tex., in Henry A. Ravia, Bessie. place of C. I. Snedecor. Incumbent's commission expired De Burton A. Tyrrell, Fargo. cember 10, 1928. Earl C. Moore, Forgan. Lydia Teller to be postmaster at Orange Grove, Tex., in place Benjamin F. R!irick, Guymon. of Lydia Teller. Incumbent's commission e1..--pired December 10, Helen Whitlock, Mru:amec. 1928. SOUTH CAROLINA Casimiro P. Alvarez to be postmaster at Riogrande, Tex., in John W. Willis, Lynchburg. place of C. P. Alvarez. Ineumbent'.s commission expired Decem- ber 10, 1928. · WEST VIRGINIA George 1\f. Sewell to be postmaster at Talpa, Tex., in place of Mary .Allen, Filbert. G. M. Sewell. Incumbent's commission expil·ed December 10, Minnie Ratliff, Yukon. 1928.-· Charles If''. Boettcher to be postmaster at Weimar, Tex., in WITHDRAWAL place of C. F. Boettcher. Incumbent's commission expired De cember 10, 1928. Exeuutive nominatio-n witlzarawn trorn the Senate Decembf:»' -14 (legislative da·y of D ecem-ber 13), 1928 UTAH POSTMASTER Carlos C. -

Santa Fe Daily New Mexican, 06-04-1897 New Mexican Printing Company

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 6-4-1897 Santa Fe Daily New Mexican, 06-04-1897 New Mexican Printing Company Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sfnm_news Recommended Citation New Mexican Printing Company. "Santa Fe Daily New Mexican, 06-04-1897." (1897). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ sfnm_news/5635 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOL. 34. SANTA FE N. Mm FRIDAY, JUNE 4, 1897. NO. 88 COMMENCEMENT EXERCISES WASHINGTON NEWS BUDGET JUDGE LYNCH'S WORK IN OHIO BONITO & URRACA DISTRICTS The Pioneers In Their Line. Fourth Annual Commencement of the DRUCS A JEWELRY Senator Mantle Asserts That the Wool A Prisoner Taken from the Urbaua, lew Mexico oneite or Agricul- Mineral Section That is Beginning ture anil mechanic Art. Growers Are Not Satisfied with Ohio, Jail and Lynched by a Mob, to Attract Widespread Attention Anions: Men. GEO. W. HICKOX & CO. the Rate? as Proposed by the Alter Having Two Men Killed The commencement exercises of the Mining; Sew Tariff Bill. and Half a Dozen Injured New Mexico College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts will be held June 6 to IIS DISCOVERY AND ITS DEVELOPMENT -- MANUFACTURERS 07-- by the Militia. A NOTE OF WARNING IS SOUNDED SI lnolusive. The order of exercises will be as follows: On June 6, at A Company of Troops from Springfield Sunday The Porphyry Dikes bo Prominent in 11 o'olook a.