Covering: Mutable Characteristics and Perceptions of Voice in the U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

M Master R Proje Ect Bib Bliogr Raphy

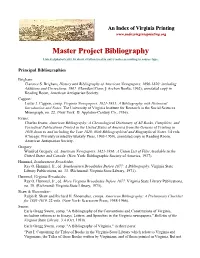

An Index of Virginia Printing www.indexvirginiaprinting.org Master Project Bibliography Listed alphabetically by short citation used in entrry notes according to source type. Principal Bibliographies Brigham: Clarence S. Brigham, History and Bibliography of American Newsppapers, 16900-1820: including Additions and Corrections, 1961. (Hamden [Conn.]: Archon Books, 1962); annotated copy in Reading Room, American Antiquarian Society. Cappon: Lester J. Cappon, comp. Virginia Newspapers, 1821-1935: A Biblioggraphy with Historical Introduction and Notes. The University of Virginia Institute for Research in the Social Sciences Monograph, no. 22. (New York: D. Appleton-Century Co., 1936). Evans: Charles Evans, American Bibliography: A Chronological Dictionary of All Books, Pamphlets, and Periodical Publications Printed in the United States of America from the Genesis of Printing in 1639 down to and including the Year 1820: With Bibliographical and Biographical Notes. 14 vols. (Chicago: Privately printed by Blakely Press, 1903-1959), annotated copy in Reading Room, American Antiquarian Society. Gregory: Winifred Gregory, ed. American Newspapers, 1821-1936: A Union List of Files Available in the United States and Canada. (New York: Bibliographic Society of America, 1937). Hummel, Southeastern Broadsides. Ray O. Hummel, Jr., ed. Southeastern Broadsides Before 1877: A Bibliography. Virginia State Library Publications, no. 33. (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1971). Hummel, Virginia Broadsides. Ray O. Hummel, Jr., ed. More ViV rginia Broadsides Beforre 1877. Virginia State Library Publications, no. 39. (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1975). Shaw & Shoemaker: Ralph R. Shaw and Richard H. Shoemaker, comps. American Bibliography: A Preliminary Checklist for 1801-1819. 22 vols. (New York: Scarecrow Press, 1958-1966). Swem: Earle Gregg Swem, comp. -

The Supreme Court 2018‐2019 Topic Proposal

The Supreme Court 2018‐2019 Topic Proposal Proposed to The NFHS Debate Topic Selection Committee August 2017 Proposed by: Dustin L. Rimmey Topeka High School Topeka, KS Page 1 of 1 Introduction Alexander Hamilton famously noted in the Federalist no. 78 “The Judiciary, on the contrary, has no influence over either the sword or the purse; no direction of either of the strength or of the wealth of the society; and can take no active resolution whatever.” However, Hamilton could be no further from the truth. From the first decision in 1793 up to the most recent decision the Supreme Court of the United States has had a profound impact on the Constitution. Precedents created by Supreme Court decisions function as one of the most powerful governmental actions. Jonathan Bailey argues “those in the legal field treat Supreme Court decisions with a near‐religious reverence. They are relatively rare decisions passed down from on high that change the rules for everyone all across the country. They can bring clarity, major changes and new opportunities” (Bailey). For all of the power and awe that comes with the Supreme Court, Americans have little to know accurate knowledge about the land’s highest court. According to a 2015 survey released by the Annenberg Public Policy Center: 32% of Americans could not identify the Supreme Court as one of our three branches of government, 28% believe that Congress has full review over all Supreme Court decisions, and 25% believe the court could be eliminated entirely if it made too few popular decisions. Because so few Americans lack solid understanding of how the Supreme Court operates, now is the perfect time for our students to actively focus on the Supreme Court in their debate rounds. -

Student Research Briefing Series

DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE ~ TUFTS UNIVERSITY STUDENT RESEARCH BRIEFING SERIES VOLUME III, ISSUE I SPRING 2014 THE SILENT MINORITY: AN EXAMINATION OF FEMALE JUSTICES OF THE SUPREME COURT DURING ORAL ARGUMENT CAROLINE HELEN HOWE The Student Research Briefing Series is designed to publish a broad range of topics in American Politics, Comparative Politics, Political Theory and Philosophy, and Interna- tional Relations. The briefings are intended to enhance student appreciation of student TABLE OF CONTENTS research completed in the Department of Political Science. In addition, the publication hopes to serve as outreach to interested undergraduates and prospective students consid- INTRODUCTION 4 ering a major in Political Science. This publication is student-produced and the research was conducted during Caroline’s undergraduate studies. To read The Silent Minority please visit http://ase.tufts.edu/polsci/studentresearch/SilentMinority.pdf. LITERATURE REVIEW 12 In The Silent Minority: An Examination of Female Justices of the Supreme Court During Oral Argument Howe seeks to recognize and substantiate the value of gender diversity on Supreme Court jurisprudence. She explores the impact of female Justices on oral ar- METHODOLOGY 35 gument from the behavior and treatment of the Justices to the content of their arguments. Howe found much of the behavior of female Justices on the Court exhibited their confi- dence and willingness to engage with their colleagues in a public and meaningful way. The presence of many “perspective statements” throughout the broad swath of gender BEHAVIOR & 45 cases also demonstrated that female Justices are unafraid to link their identity with their TREATMENT speech when it comes to gender cases. -

This Is the Cover

The McNair Scholars Journal of the University of Washington Volume XIII Autumn 2013 THE MCNAIR SCHOLARS JOURNAL University of Washington McNair Program Office of Minority Affairs & Diversity University of Washington 171 Mary Gates Hall Box 352803 Seattle, WA 98195-2803 [email protected] http://depts.washington.edu/uwmcnair/ The Ronald E. McNair Postbaccalaureate Achievement Program operates as a part of TRiO Programs, which are funded by the U.S. Department of Education. Cover Photo by Merzamie Cagaitan, UW McNair Alumnus University of Washington McNair Program Staff Program Director Gabriel Gallardo, Ph.D. Associate Director Gene Kim, Ph.D. Program Coordinator Rosa Ramirez Graduate Student Advisors Brooke Cassell Raj Chetty McNair Scholars’ Research Mentors Dr. Brittany Brand, Earth and Space Sciences Dr. Eliot Brenowitz, Biology and Psychology Dr. Katherine Cummings, English Dr. Angela Ginorio, Gender, Women and Sexuality Studies; Psychology Dr. Ricardo Gomez, Information School Dr. Michelle Habell-Pallán, Women Studies Dr. Steve Herbert, Law, Societies, and Justice Dr. Jerald Herting, Sociology Dr. Nancy Hertzog, Educational Psychology Dr. Marketa Hnilova, Materials Science & Engineering Dr. Kimberly Hudson, School of Social Work Dr. Horacio O. de la Iglesia, Biology Dr. Hedwig Lee, Sociology Dr. Mary Lidstrom, Microbiology and Chemical Engineering Dr. Michelle S. Liu, English Dr. Ralf Luche, Psychology Dr. N. Cecilia Martinez-Gomez, Microbiology Dr. Devon G. Peña, American Ethnic Studies and Anthropology Dr. Carolyn Pinedo-Turnovsky, American Ethnic Studies Dr. Nicholas Poolos, Neurobiology and Behavior Dr. Fernando Resende, Environmental and Forest Sciences Dr. Sonnet Retman, American Ethnic Studies Dr. Natasha Rivers, Demography and Ecology Dr. Ileana M. Rodriguez-Silva, History Mr. -

How to Read a U.S. Supreme Court Opinion

Social Education 77(1), pp 32–35 ©2013 National Council for the Social Studies Looking at the Law How to Read a U.S. Supreme Court Opinion Tiffany Middleton Reading U.S. Supreme Court opinions can be intimidating. Yet, in the digital age, it Brown, for example, was a unanimous has never been easier to access them. The average opinion is about 4,750 words, and opinion with all nine justices agreeing is one of approximately 75 issued by the Court each year. It might be reassuring to on the decision and the legal rationale. know that opinions contain similar parts and tend to follow a similar format. There When more than half of the justices agree are also useful key words to identify amid the pages of a PDF or HTML text to on the same result and the rationale, the help focus reading. Here, “Looking at the Law” offers a basic guide for reading and Court issues a majority opinion. Tinker v. analyzing these important primary legal documents. Des Moines, for example, was a majority opinion, with seven justices ruling for the Step 1: Identify the Parts. syllabus with a heading: “Opinion of the petitioner, Tinker, and agreeing with the Typically, a U.S. Supreme Court opinion Court,” or will announce a particular rationale, and two justices not in agree- document is comprised of one or more, justice delivering the opinion for the ment with the majority.4 or all, of the following: Court. Typically, one justice is identi- Other times, there is no majority, but fied as the author of the main opinion, as a plurality, so the Court issues a plural- Syllabus in “Mr. -

Resources for Mother-Child Community Corrections

RESOURCES FOR MOTHER-CHILD COMMUNITY CORRECTIONS By: Mary K. Shilton The Mother-Child Community Corrections Project International Community Corrections Association P.O. Box 1987 La Crosse, WI 54602 This project was supported by cooperative agreement 2000-DD-VX-0015 awarded by the Bureau of Justice Assistance, Office of Justice Programs, and the U.S. Department of Justice. Points of view in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent official positions or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This Guide was developed with the assistance of The Mother-Child Community Corrections Project Team Judy Berman, Center for Effective Public Policy Karen Chapple, International Community Corrections Association Phyllis Modley, National Institute of Corrections Becki Ney, Center for Effective Public Policy Mary Shilton, International Community Corrections Association Richard A. Sutton, Bureau of Justice Assistance, U.S. Department of Justice PROJECT ADVISORY GROUP Karen Asphaug, First Judicial District, Hastings, MN Sandra Barnhill, Aid to Children of Imprisoned Mothers, Atlanta, GA Evvie Becker, Ph.D., Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, D.C Carl C. Bell, M.D., Community Mental Health Council, Chicago, IL Barbara Bloom Ph.D. CSU, Dept. of Criminal Justice, Petaluma, CA Barbara Broderick, Arizona Supreme Court Admin. Office of the Courts, Phoenix, AZ Patsy L. Buida, M.S.W., Children’s Bureau, Washington, D.C. Sonia L. Burgos, Dept. of Housing and Urban Development, Washington, D.C. Ellen Clark, Western Carolinians for Criminal Justice, Women at Risk program, Ashville, NC Stephanie S. Covington, Ph.D., Institute for Relational Development, La Jolla, CA Teresa Fabi, Kings County District Attorney’s Office, Brooklyn, NY Mindy Feldbaum, U.S. -

Commerce Clause New Federalism in the Rehnquist and Roberts Courts: Dynamics of Culture Wars Constitutionalism, 1964-2012 ___

COMMERCE CLAUSE NEW FEDERALISM IN THE REHNQUIST AND ROBERTS COURTS: DYNAMICS OF CULTURE WARS CONSTITUTIONALISM, 1964-2012 ______________________________ A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School University of Missouri ________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy ________________________________ by ROGER E. ROBINSON Dr. Mark M. Carroll, Dissertation Supervisor December 2017 © Copyright by Roger E. Robinson 2017 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled COMMERCE CLAUSE NEW FEDERALISM IN THE REHNQUIST AND ROBERTS COURTS: DYNAMICS OF CULTURE WARS CONSTITUTIONALISM, 1964-2012 presented by Roger Robinson, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Mark M. Carroll, Associate Professor of History, Chair William B. Fisch, Professor Emeritus of Law Robert M. Collins, Professor Emeritus of History John L. Bullion, Professor Emeritus of History Catherine Rymph, Associate Professor of History DEDICATION On the home front, my wife, Mary Kay, helped me figure out that an academic career should be in my future after retiring from the Air Force. She’s been my biggest supporter, counselor, and editor even though the process has included a move, a new job, homeschooling, and the birth of two children in the interim. Equally patient and supportive have been my kids, Benjamin, Arianna, James, Isaac, Joseph, Abigail, and Levi, all of whom are very pleased that the project is now complete. This work, therefore is dedicated to my family without whose love and support I’d have never succeeded. -

Free Culture and the Digital Library Symposium Proceedings 2005

Free Culture and the Digital Library Symposium Proceedings 2005 Proceedings of a Symposium held on October 14, 2005 at Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia. Martin Halbert (Editor) MetaScholar Initiative Robert W. Woodruff Library Emory University Atlanta, Georgia This work is published under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License Copyright Information: These proceedings are covered by the following Creative Commons License: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 You are free to copy, distribute, and display this work under the following conditions: Attribution. You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor. Specifically, you must state that the work was originally published in the Free Culture and the Digital Library Symposium Proceedings 2005, and you must attribute the author(s). Noncommercial. You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works. You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder. Your fair use and other rights are in no way affected by the above. The above is a human-readable summary of the full license, which is available at the following URL: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/legalcode Publication and Cataloging Information: ISBN: 0-9772994-0-6 Editor: Martin Halbert Copy Editors: Carrie Finegan Katherine Skinner Publisher: MetaScholar Initiative -

Brief for Class Respondents ————

No. 17-961 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States ———— THEODORE H. FRANK, ET AL., Petitioners, v. PALOMA GAOS, INDIVIDUALLY AND ON BEHALF OF ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED, ET AL., Respondents. ———— On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ———— BRIEF FOR CLASS RESPONDENTS ———— KASSRA P. NASSIRI JEFFREY A. LAMKEN Counsel of Record MICHAEL G. PATTILLO, JR. NASSIRI & JUNG LLP JAMES A. BARTA 47 Kearny St. WILLIAM J. COOPER Suite 700 MOLOLAMKEN LLP San Francisco, CA 94108 The Watergate, Suite 660 (415) 762-3100 600 New Hampshire Ave., N.W. [email protected] Washington, D.C. 20037 (202) 556-2000 [email protected] Counsel for Class Respondents (Additional Counsel Listed on Inside Cover) :,/621(3(635,17,1*&2,1&± ±:$6+,1*721'& MICHAEL ASCHENBRENER JUSTIN B. WEINER KAMBERLAW, LLC JORDAN A. RICE 201 Milwaukee St. MOLOLAMKEN LLP Suite 200 300 N. LaSalle St. Denver, CO 80206 Chicago, IL 60654 (303) 222-0281 (312) 450-6700 [email protected] QUESTION PRESENTED Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23(b)(3) permits rep- resentatives to maintain a class action where so doing “is superior to other available methods for fairly and effi- ciently adjudicating the controversy,” and Rule 23(e)(2) requires that a settlement that binds class members must be “fair, reasonable, and adequate.” The question pre- sented is: Whether, or in what circumstances, a class-action set- tlement that provides a cy pres award of class-action proceeds but no direct relief to class members comports with the requirement that a settlement binding class members must be “fair, reasonable, and adequate” and supports class certification.