This Is the Cover

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Index of /Sites/Default/Al Direct/2008/July

AL Direct, July 2, 2008 Contents U.S. & World News ALA News Booklist Online Division News Awards Seen Online Tech Talk Publishing The e-newsletter of the American Library Association | July 2, 2008 Actions & Answers Calendar U.S. & World News Mesa board cuts librarians “It’s not over. We’re going to continue to do what we can both in Mesa and in Arizona,” Fund Our Future Arizona spokesperson Ann Ewbank told American Libraries June 27, three days after the Mesa Public School board implemented as part of its FY2008–09 budget the replacement over three years of every school library media specialist in the district with library aides. Other Arizona school systems now eyeing the cost of school library programs are the Humboldt Unified School District in Prescott Valley and the Glendale Elementary School District.... Bay County director hired after two-year hiatus After two years without a director, Bay County (Mich.) Library System has appointed Thomas H. Birch Jr. to the position, effective July 21. Birch’s appointment comes some six months after voters approved an For news of ALA Annual operating-millage renewal that was 2/10ths of a mill less than two 1- Conference, see AL mill levies that were defeated in 2006. “We’re feeling very good about Direct’s special post- moving ahead on a whole variety of things,” board Chairman Don conference issue, to be Carlyon told American Libraries.... emailed Monday, July 7. OCLC: National marketing campaign could hike funding From Awareness to Funding: A Study of Library Support in America, a new report issued by OCLC, examines the potential of a national marketing campaign to increase awareness of the value of public libraries and the need for support for libraries at local, state, and national levels. -

Hux Course Syllabus Template

Bound Slave by Michelangelo HUMANITIES 532 SLAVERY IN HISTORY AND LITERATURE California State University, Dominguez Hills Humanities Master of Arts External Program (HUX) www.csudh.edu/hux HUXCRSGD. 532 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Prerequisites page 4 II. Course Description page 4 III. Books Required page 4 IV. Course-Level Student Learning Goals page 5 V. Description of Student Activities to Fulfill Goals page 5 VII. Grading Policy page 6 VIII. HUX Academic Integrity Statement page 6 IX. Course Organization page 7 X. Schedule of Readings page 7 XI. Writing Assignments page 8 XII. page 10 Websites XIII. Introduction page 14 XIV. The Nature of Slavery page 15 XV. Origins of Slavery page 31 XVI. Slavery in the Ancient Near East page 32 XVII. Slavery in Ancient Greece page 34 XVIII. Slavery in Medieval Europe page 43 XIX. Slavery in the Islamic World page 47 XX. Slavery in Africa page 49 2 HUXCRSGD. 532 XXI. The Transatlantic Slave Trade page 55 XXII. Slavery in the New World page 61 XXIII. American Slavery page 69 XXIV. Slave Narratives page 78 XXV. The African-American Slave Community page 83 XXVI. The Ante-Bellum South and the Civil War page 89 XXVII. Slavery in the Modern World page 97 Course design by Dr. Bryan Feuer, October 2001. PLEASE NOTE: Due dates have been revised due to the new 14 week calendar. 3 HUXCRSGD. 532 PREREQUISITES: HUX 501 COURSE DESCRIPTION Examines the institution of slavery from an interdisciplinary humanistic perspective utilizing a comparative approach. Surveys slavery from ancient times to the present in all parts of the world, with focus upon American slavery. -

Awards Appendix

Appendix A: Awards Jane Addams Book Award The Jane Addams Children’s Book Award has been presented annually since 1953 by the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom and the Jane Addams Peace Association to the children’s book of the preceding year that most effectively promotes the cause of peace, social justice and world community 1953 People Are Important by Eva Knox Evans (Capital) 1954 Stick-in-the-Mud by Jean Ketchum (Cadmus Books, E.M. Hale) 1955 Rainbow Round the World by Elizabeth Yates (Bobbs-Merrill) 1956 Story of the Negro by Arna Bontemps (Knopf) 1957 Blue Mystery by Margot Benary-Isbert (Harcourt Brace) 1958 The Perilous Road by William O. Steele (Harcourt Brace) 1959 No Award Given 1960 Champions of Peace by Edith Patterson Meyer (Little, Brown) 1961 What Then, Raman? By Shirley L. Arora (Follett) 1962 The Road to Agra by Aimee Sommerfelt (Criterion) 1963 The Monkey and the Wild, Wild Wind by Ryerson Johnson (Abelard-Schuman) 1964 Profiles in Courage: Young Readers Memorial Edition by John F. Kennedy (Harper & Row) 1965 Meeting with a Stranger by Duane Bradley (Lippincott) 1966 Berries Goodman by Emily Cheney Nevel (Harper & Row) 1967 Queenie Peavy by Robert Burch (Viking) 1968 The Little Fishes by Erick Haugaard (Houghton Mifflin) 1969 The Endless Steppe: Growing Up in Siberia by Esther Hautzig (T.Y. Crowell) 1970 The Cay by Theodore Taylor (Doubleday) 1971 Jane Addams: Pioneer of Social Justice by Cornelia Meigs (Little, Brown) 1972 The Tamarack Tree by Betty Underwood (Houghton Mifflin) 1973 The Riddle of Racism by S. -

Appendix B: a Literary Heritage I

Appendix B: A Literary Heritage I. Suggested Authors, Illustrators, and Works from the Ancient World to the Late Twentieth Century All American students should acquire knowledge of a range of literary works reflecting a common literary heritage that goes back thousands of years to the ancient world. In addition, all students should become familiar with some of the outstanding works in the rich body of literature that is their particular heritage in the English- speaking world, which includes the first literature in the world created just for children, whose authors viewed childhood as a special period in life. The suggestions below constitute a core list of those authors, illustrators, or works that comprise the literary and intellectual capital drawn on by those in this country or elsewhere who write in English, whether for novels, poems, nonfiction, newspapers, or public speeches. The next section of this document contains a second list of suggested contemporary authors and illustrators—including the many excellent writers and illustrators of children’s books of recent years—and highlights authors and works from around the world. In planning a curriculum, it is important to balance depth with breadth. As teachers in schools and districts work with this curriculum Framework to develop literature units, they will often combine literary and informational works from the two lists into thematic units. Exemplary curriculum is always evolving—we urge districts to take initiative to create programs meeting the needs of their students. The lists of suggested authors, illustrators, and works are organized by grade clusters: pre-K–2, 3–4, 5–8, and 9– 12. -

The Significance of Topics of Orbis Pictus Award–Winning Books

42 Elaine M. Aoki The Significance of 5 Topics of Orbis Pictus Award–Winning Books Elaine M. Aoki Bush School, Seattle, Washington he designation of an award is evidence of something unique. Orbis Pictus Award–winning texts and honor books are distin- T guished from other nonfiction works by their presentation and treatment of topics and issues. Examining an award-winning text with a critical eye allows us to view the many facets of the work. Each facet, however, forms but a small part of the total image. We see the “individualness” of detail, but only when we combine all the parts and envision the entire work are we able to form a final critical assessment of the value of the contribution. Key among Orbis Pictus Award Committee concerns when assessing books are the following: What is the potential impact of this text? Is the presentation “time- less,” enabling the reader to draw analogies to other events occur- ring in different contexts? What is the relationship of the subject to contemporary concerns? And, finally, to what extent does the text enlighten, enhance, or illuminate curricular issues? Consideration of such elements allows committee members to identify a text as one exhibiting that special potential to stimulate the interest, curiosity, and imagination of the young reader. Defining What makes a topic significant? Are significant topics found only within designated “factual” genres such as biography, history, and Significance science? Readers evaluate the significance of a text in light of their experiences. What makes a work significant is the degree to which the subject is part of a collective social consciousness and whether the text is accessible at precisely the right time in the life of a reader or, as in the case of the committee, a community of readers. -

Association for Library Service to Children

ASSOCIATION FOR LIBRARY SERVICE TO CHILDREN LAURA INGALLS WILDER AWARD COMMITTEE MANUAL August 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD 4 PART I. BACKGROUND INFORMATION 5 History and Purpose 6 Committee Function Statement 6 The Committee 6 Terms, Definitions, Criteria 7 Priority Group Consultant 8 ALSC Policies 8 ALSC Policy for Service on the Laura Ingalls Wilder Medal Selection Committee 8 Conflict of Interest 8 Confidentiality 9 Guidelines for Award Committees 9 Attendance at Meetings and Access to Materials 10 Frequency of Service on the Wilder Committee 10 Checklist for Prospective Wilder Committee Members 11 Relationships with Publishers 12 Electronic Communication 12 PART II. COMMITTEE WORK 15 Welcome 16 Calendar 16 Attendance at Meetings 16 Schedule of Events 17 Access to Materials 20 Communication 20 Suggested Voting Procedures 20 Preparation 21 Eligibility 21 Diversity and Inclusion 21 Note-Taking 21 Suggestion Process 22 Participation of ALSC Membership 22 Committee Participation 23 Review of Confidentiality of Discussion and Selection 24 2 PART III. ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES 25 Introduction 26 Committee Chair 26 Priority Group Consultant 27 ALSC Staff 27 ALSC Membership 27 ALSC Board 27 ALSC President 27 Public Information Office (PIO) 28 PART IV. APPENDIX 29 Sample Employer/Supervisor Information 30 Sample Letters to Committee Members’ Employers/Supervisors 31 Sample Note-Taking Form 33 Sample Nomination Ballot 35 Sample Selection Ballot 35 Sample Voting Tally Sheet 37 Sample Press Release 38 Sample Congratulations Letter to Winner 40 List of Wilder Award Winners 42 This manual attempts to outline the practices, procedures and principles to follow in the selection and presentation of the Wilder Award. -

ISBN TITLE AUTHOR PUBLISHER/MMEDIUM AREA SHELF LOCATION QUANT 9780761453482 Born for Adventure Kathleen Karr Two Lions Hardcover

ISBN TITLE AUTHOR PUBLISHER/MMEDIUM AREA SHELF LOCATION QUANT 9780761453482 Born for Adventure Kathleen Karr Two Lions Hardcover Ackerman Children's Literature: Africa 1 9780374371784 Time's Memory Julius Lester Farrar Straus GHardcover Ackerman Children's Literature: Africa 1 At the Crossroads Rachel Isadora Greenwillow Hardcover Ackerman Children's Literature: Africa 1 9780517885444 Tar Beach Faith Ringgold Dragonfly BooPaperback Ackerman Children's Literature: Africa 1 Never Forgotten Patricia McKissack Schwartz and Hardcover Ackerman Children's Literature: Africa 1 9781563978227 Madoulina (Story from West Africa) Joe Bognomo Boyds Mills PrPaperback Ackerman Children's Literature: Africa 1 9780374312893 Circle Unbroken Margot Theis Raven Farrar, Straus Hardcover Ackerman Children's Literature: Africa 1 9780688102562 African Beginnings Kathleen Benson; James Haskins Amistad Hardcover Ackerman Children's Literature: Africa 1 9780688151782 Storytellers, The Ted Lewin Harpercollins Hardcover Ackerman Children's Literature: Africa 1 9780027814903 Abiyoyo Pete Seeger Simon and SchHardcover Ackerman Children's Literature: Africa 1 9780671882686 Fire on the Mountain Earl B. Lewis Simon & SchuHardcover Ackerman Children's Literature: Africa 1 9780690013344 Honey, I Love and Other Love Poems Eloise Greenfield HarperCollins Hardcover Ackerman Children's Literature: Africa 1 9780545270137 One Hen: How One Small Load Made a Big Difference Katie Smith Milway Scholastic Paperback Ackerman Children's Literature: Africa 2 Man of the People: A Novel -

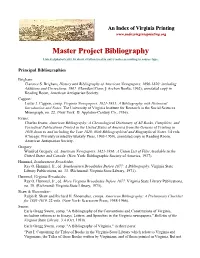

M Master R Proje Ect Bib Bliogr Raphy

An Index of Virginia Printing www.indexvirginiaprinting.org Master Project Bibliography Listed alphabetically by short citation used in entrry notes according to source type. Principal Bibliographies Brigham: Clarence S. Brigham, History and Bibliography of American Newsppapers, 16900-1820: including Additions and Corrections, 1961. (Hamden [Conn.]: Archon Books, 1962); annotated copy in Reading Room, American Antiquarian Society. Cappon: Lester J. Cappon, comp. Virginia Newspapers, 1821-1935: A Biblioggraphy with Historical Introduction and Notes. The University of Virginia Institute for Research in the Social Sciences Monograph, no. 22. (New York: D. Appleton-Century Co., 1936). Evans: Charles Evans, American Bibliography: A Chronological Dictionary of All Books, Pamphlets, and Periodical Publications Printed in the United States of America from the Genesis of Printing in 1639 down to and including the Year 1820: With Bibliographical and Biographical Notes. 14 vols. (Chicago: Privately printed by Blakely Press, 1903-1959), annotated copy in Reading Room, American Antiquarian Society. Gregory: Winifred Gregory, ed. American Newspapers, 1821-1936: A Union List of Files Available in the United States and Canada. (New York: Bibliographic Society of America, 1937). Hummel, Southeastern Broadsides. Ray O. Hummel, Jr., ed. Southeastern Broadsides Before 1877: A Bibliography. Virginia State Library Publications, no. 33. (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1971). Hummel, Virginia Broadsides. Ray O. Hummel, Jr., ed. More ViV rginia Broadsides Beforre 1877. Virginia State Library Publications, no. 39. (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1975). Shaw & Shoemaker: Ralph R. Shaw and Richard H. Shoemaker, comps. American Bibliography: A Preliminary Checklist for 1801-1819. 22 vols. (New York: Scarecrow Press, 1958-1966). Swem: Earle Gregg Swem, comp. -

The Supreme Court 2018‐2019 Topic Proposal

The Supreme Court 2018‐2019 Topic Proposal Proposed to The NFHS Debate Topic Selection Committee August 2017 Proposed by: Dustin L. Rimmey Topeka High School Topeka, KS Page 1 of 1 Introduction Alexander Hamilton famously noted in the Federalist no. 78 “The Judiciary, on the contrary, has no influence over either the sword or the purse; no direction of either of the strength or of the wealth of the society; and can take no active resolution whatever.” However, Hamilton could be no further from the truth. From the first decision in 1793 up to the most recent decision the Supreme Court of the United States has had a profound impact on the Constitution. Precedents created by Supreme Court decisions function as one of the most powerful governmental actions. Jonathan Bailey argues “those in the legal field treat Supreme Court decisions with a near‐religious reverence. They are relatively rare decisions passed down from on high that change the rules for everyone all across the country. They can bring clarity, major changes and new opportunities” (Bailey). For all of the power and awe that comes with the Supreme Court, Americans have little to know accurate knowledge about the land’s highest court. According to a 2015 survey released by the Annenberg Public Policy Center: 32% of Americans could not identify the Supreme Court as one of our three branches of government, 28% believe that Congress has full review over all Supreme Court decisions, and 25% believe the court could be eliminated entirely if it made too few popular decisions. Because so few Americans lack solid understanding of how the Supreme Court operates, now is the perfect time for our students to actively focus on the Supreme Court in their debate rounds. -

Covering: Mutable Characteristics and Perceptions of Voice in the U.S

TSE‐680 July 2016 “Covering: Mutable characteristics and perceptions of voice in the U.S. Supreme Court” Daniel L. Chen, Yosh Halberstam, and Alan Yu COVERING: MUTABLE CHARACTERISTICS AND PERCEPTIONS OF VOICE IN THE U.S. SUPREME COURT Daniel L. Chen, Yosh Halberstam, and Alan Yu∗ Abstract The emphasis on “fit” as a hiring criterion has raised the spectrum of a new form of subtle discrimination (Yoshino 1998; Bertrand and Duflo 2016). Under complete markets, correlations between employee characteristics and outcomes persist only if there exists animus for the marginal employer (Becker 1957), but who is the marginal employer for mutable characteristics? Using data on 1,901 U.S. Supreme Court oral arguments between 1998 and 2012, we document that voice-based snap judgments based on lawyers’ identical introductory sentences, “Mr. Chief Justice, (and) may it please the Court?”, predict court outcomes. The connection between vocal characteristics and court outcomes is specific only to perceptions of masculinity and not other characteristics, even when judgment is based on less than three seconds of exposure to a lawyer’s speech sample. Consistent with employers irrationally favoring lawyers with masculine voices, perceived masculinity is negatively correlated with winning and the neg- ative correlation is larger in more masculine-sounding industries. The first lawyer to speak is the main driver. Among these petitioners, males below median in masculinity are 7 percentage points more likely to win in the Supreme Court. Justices appointed by Democrats, but not Republicans, vote for less- masculine men. Female lawyers are also coached to be more masculine and women’s perceived femininity predict court outcomes. -

Adult Author's New Gig Adult Authors Writing Children/Young Adult

Adult Author's New Gig Adult Authors Writing Children/Young Adult PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 31 Jan 2011 16:39:03 UTC Contents Articles Alice Hoffman 1 Andre Norton 3 Andrea Seigel 7 Ann Brashares 8 Brandon Sanderson 10 Carl Hiaasen 13 Charles de Lint 16 Clive Barker 21 Cory Doctorow 29 Danielle Steel 35 Debbie Macomber 44 Francine Prose 53 Gabrielle Zevin 56 Gena Showalter 58 Heinlein juveniles 61 Isabel Allende 63 Jacquelyn Mitchard 70 James Frey 73 James Haskins 78 Jewell Parker Rhodes 80 John Grisham 82 Joyce Carol Oates 88 Julia Alvarez 97 Juliet Marillier 103 Kathy Reichs 106 Kim Harrison 110 Meg Cabot 114 Michael Chabon 122 Mike Lupica 132 Milton Meltzer 134 Nat Hentoff 136 Neil Gaiman 140 Neil Gaiman bibliography 153 Nick Hornby 159 Nina Kiriki Hoffman 164 Orson Scott Card 167 P. C. Cast 174 Paolo Bacigalupi 177 Peter Cameron (writer) 180 Rachel Vincent 182 Rebecca Moesta 185 Richelle Mead 187 Rick Riordan 191 Ridley Pearson 194 Roald Dahl 197 Robert A. Heinlein 210 Robert B. Parker 225 Sherman Alexie 232 Sherrilyn Kenyon 236 Stephen Hawking 243 Terry Pratchett 256 Tim Green 273 Timothy Zahn 275 References Article Sources and Contributors 280 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 288 Article Licenses License 290 Alice Hoffman 1 Alice Hoffman Alice Hoffman Born March 16, 1952New York City, New York, United States Occupation Novelist, young-adult writer, children's writer Nationality American Period 1977–present Genres Magic realism, fantasy, historical fiction [1] Alice Hoffman (born March 16, 1952) is an American novelist and young-adult and children's writer, best known for her 1996 novel Practical Magic, which was adapted for a 1998 film of the same name. -

160152742Xslavery Worldhistory.Biz

Other titles in the series include: Ancient Chinese Dynasties Ancient Egypt Ancient Greece Ancient Rome e Black Death e Decade of the 2000s e Digital Age e Early Middle Ages Elizabethan England e Enlightenment e Great Recession e History of Rock and Roll e Holocaust e Industrial Revolution e Late Middle Ages e Making of the Atomic Bomb Pearl Harbor e Renaissance e Rise of Islam e Rise of the Nazis Victorian England Understanding World History The History of Slavery Hal Marcovitz Bruno Leone Series Consultant ® San Diego, CA 3 ® © 2015 ReferencePoint Press, Inc. Printed in the United States For more information, contact: ReferencePoint Press, Inc. PO Box 27779 San Diego, CA 92198 www. ReferencePointPress.com ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, web distribution, or information storage retrieval systems—without the written permission of the publisher. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Marcovitz, Hal. The history of slavery / by Hal Marcovitz. pages cm.—(Understanding world history) Audience: Grade 9 to 12. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-1-60152-743-1 (e-book) 1. Slavery—History--Juvenile literature. I. Title. HT861.M27 2015 306.3'6209--dc23 2014010454 Contents Foreword 6 Important Events in the History of Slavery 8 Introduction 10 e Defi ning Characteristics of Slavery Chapter One 14 What Conditions Led to Slavery? Chapter Two 27 Slaves of the Medieval Era Chapter ree 41 Slavery in the New World Chapter Four 56 Slavery in the Modern Era Chapter Five 69 What Is the Legacy of Slavery? Source Notes 82 Important People in the History of Slavery 85 For Further Research 88 Index 91 Picture Credits 95 About the Author 96 Foreword hen the Puritans fi rst emigrated from England to America in W 1630, they believed that their journey was blessed by a cov- enant between themselves and God.