Africans in America Teacher's Guide PDF (Color)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Session 2 Home Ownership=Wealth Accumulation JCC Arts and Culture

12/17/2020 Session 2 Home Ownership=Wealth Accumulation 1 JCC Arts and Culture Program Lev Rothenberg Director of Arts and Education 2 1 12/17/2020 Welcome and More…. Rules of the Road: • So glad you are here! • 2 parts: Presentation + Conversation. • Everyone’s voice is important. • Jot down your questions/comments. • Mute during presentation. • Raise your HAND to be recognized. • Do NOT use Chat. It is disruptive. Thank You! 3 From Last Week Any “Aha” moments to share from last week’s discussion, “History of Racism”? 4 2 12/17/2020 What is Racism? • Racism is commonly defined as “Prejudice + Power. • Prejudice is used against someone based on his/her race. • Racism is a belief that certain racial groups are superior to others and have rights and power over others. Racism can be manifested through beliefs, policies, attitudes and actions by governments, organizations and individuals. 5 What Is Systemic Racism? • It is Prejudice expressed through the Power of governments, institutions, organizations, policies and laws. • Systemic, Structural and Institutional Racism are often used interchangeably. For our purposes. .We will use the term Systemic Racism. 6 3 12/17/2020 The “Other Story” Much of our country’s history is from a White perspective, but . There is Another Story about Free Blacks and their relationship with govt. institutions 7 Wealth Accumulation Reviewing sources of wealth. • Household items Crops • Slaves Livestock • Land Precious metals • Buildings/homes Currency – (later) • Stocks/securities (First in1790’s in Philadelphia) Enslaved Africans in America had NO wealth. They were considered a Source of wealth. 8 4 12/17/2020 Early Colonists We all know . -

Channel Guide Fusion.Indd

FUSION 1000 HIT LIST [TVE] 1025 SWINGING STANDARDS [TVE] LOCAL RADIO STATIONS 1001 URBAN BEATS [TVE] 1026 KIDS STUFF [TVE] 1051 THE LEGENDS 1300 KPMI 1002 JAMMIN’ [TVE] 1027 COUNTRY AMERICANA [TVE] 1052 1320 KOZY 1003 DANCE CLUBBIN’ [TVE] 1028 HOT COUNTRY [TVE] 1054 TALK RADIO 1360 KKBJ 1004 GROOVE [TVE] 1029 COUNTRY CLASSICS [TVE] 1055 SPORTS RADIO 1450 KBUN 1005 THE CHILL LOUNGE [TVE] 1030 FOLK ROOTS [TVE] 1059 KOJB THE EAGLE 105.3 1006 THE LIGHT [TVE] 1031 BLUEGRASS [TVE] 1061 FM 90 KBSB 1007 CLASSIC R’N’B & SOUL [TVE] 1032 HOLIDAY HITS [TVE] 1064 THE RIVER 92.1 WMIS 1008 SOUL STORM [TVE] 1033 JAZZ MASTERS [TVE] 1066 95.5 KZY 1009 GOSPEL [TVE] 1034 SMOOTH JAZZ [TVE] 1067 96.7 KKCQ 1010 NO FENCES [TVE] 1035 JAZZ NOW [TVE] 1068 96.9 KMFY 1011 CLASSIC ROCK [TVE] 1036 JAZZ/BLUES [TVE] 1070 REAL COUNTRY 98.3 WBJI 1012 ALT CLASSIC ROCK [TVE] 1037 HIP HOP [TVE] 1071 99.1 Z99 1013 ROCK [TVE] 1038 EASY LISTENING [TVE] 1073 KB101 CONTINUOUS COUNTRY 1014 HEAVY METAL [TVE] 1039 THE SPA [TVE] 1074 MIX 103.7 KKBJ 1015 ROCK ALTERNATIVE [TVE] 1040 CHAMBER MUSIC [TVE] 1075 KAXE 105.3 1016 CLASSIC MASTERS [TVE] 1041 LATINO URBANA [TVE] 1076 QFM KKEQ PBTV 1017 ADULT ALTERNATIVE [TVE] 1042 TODAY’S LATIN POP [TVE] 1077 104.5 THE BUN 2.0 1018 POPULAR CLASSICAL [TVE] 1043 LATINO TROPICAL [TVE] 1078 J105 THE THUNDER 1019 POP ADULT [TVE] 1044 ROMANCE LATINO [TVE] 1079 THE BRIDGE 91.9 KXBR CHANNEL 1020 NOTHIN’ BUT 90’S [TVE] 1045 RETRO LATINO [TVE] 1080 PSALM 99.5 KBHW 1021 EVERYTHING 80’S [TVE] 1046 ROCK EN ESPANOL [TVE] 1082 SANCTUARY 99.5 KBHW3 1022 FLASHBACK 70’S [TVE] 1047 BROADWAY [TVE] 1085 COYOTE 102.5 KKWB 1023 JUKEBOX OLDIES [TVE] 1048 ECLECTIC ELECTRONIC [TVE] 1088 RADIO TALKING BOOK LINE-UP 1024 MAXIMUM PARTY [TVE] 1049 Y2K [TVE] NOVEMBER 2019 MOVIES PREMIUM MOVIE 400 HBO (EAST) 468 STARZ KIDS & FAMILY CHANNELS 401 HBO 2 469 STARZ CINEMA 402 HBO SIGNATURE 470 STARZ IN BLACK 11 HBO CHANNELS 403 HBO FAMILY 471 STARZ (WEST) 19.95/MO. -

Read the VT on TV Timeline

- - A chronicleof independentsand smallformat, hardware and programming,events and decisionsleading up to the widespread acceptance of portablevideo on broadcasttelevision. CBS investigates portable video. 1937 1958 December. SQN, independently incorporated , NBC television mobile unit. 50,000,000 TV's. though operating out of CBS headquarters , In action in NYC. Consisting of two huge spends almost $100,000 on a portable video, buses. One crammed with a studio and the 8mm and 16mm presentation held at the other housing the transmitter that relayed 1960 Videofreex studio . Mike Dann, head of CBS programs to the Empire State Building for re programming rejects the work , predicting that broadcast. Networks ban independent news. NBC-TV explained that its obligation "for ob it will be 5 years before "television would be jective , fair and responsible presentation of ready" for that kind of material. CBS ended the news developments and issues " required up confiscating the tapes , later reclaimed by 1947 this change in policy. At this time, Robert Drew Don West , executive producer of the venture , Network news shows add new sf i Im. of Time, Inc. formed a film production group who failed to peddle them elsewhere . Crew in From.outside producers to their 15 min. consisting of Ricky Leacock, D.A. Pennebaker , cluded staff at Media Center in Lanesville evening telecasts . CBS uses Telenews, shoot T. McCartney-Filgate and Albert Maysle to along with Eric Segal, David Cort , and Da~id ing 16mm film, considered less professional produce Primary, a verite style documentary son Gigliotti. Controversial figures appearing than 35 mm, used by Fox Movietone , serving of the Kennedy and Humphrey primaries . -

Annotated Bibliography -- Trailtones

Annotated Bibliography -- Trailtones Part Three: Annotated Bibliography Contents: Abdul, Raoul. Blacks in Classical Music. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1977. [Mentions Tucson-born Ulysses Kay and his 'New Horizons' composition, performed by the Moscow State Radio Orchestra and cited in Pravda in 1958. His most recent opera was Margeret Walker's Jubilee.] Adams, Alice D. The Neglected Period of Anti-Slavery n America 1808-1831. Gloucester, Massachusetts: Peter Smith, 1964. [Charts the locations of Colonization groups in America.] Adams, George W. Doctors in Blue: the Medical History of the Union Army. New York: Henry Schuman, 1952. [Gives general information about the Civil War doctors.] Agee, Victoria. National Inventory of Documentary Sources in the United States. Teanack, New Jersey: Chadwick Healy, 1983. [The Black History collection is cited . Also found are: Mexico City Census counts, Arizona Indians, the Army, Fourth Colored Infantry, New Mexico and Civil War Pension information.] Ainsworth, Fred C. The War of the Rebellion Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. General Index. [Volumes I and Volume IV deal with Arizona.] Alwick, Henry. A Geography of Commodities. London: George G. Harrop and Co., 1962. [Tells about distribution of workers with certain crops, like sugar cane.] Amann, William F.,ed. Personnel of the Civil War: The Union Armies. New York: Thomas Yoseloff, 1961. [Gives Civil War genealogy of the Black Regiments that moved into Arizona from the United States Colored troops.] American Folklife Center. Ethnic Recordings in America: a Neglected Heritage. Washington: Library of Congress, 1982. [Talks of the Black Sacred Harping Singing, Blues & Gospel and Blues records of 1943- 66 by Mike Leadbetter.] American Historical Association Annual Report. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 103/Thursday, May 28, 2020

32256 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 103 / Thursday, May 28, 2020 / Proposed Rules FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS closes-headquarters-open-window-and- presentation of data or arguments COMMISSION changes-hand-delivery-policy. already reflected in the presenter’s 7. During the time the Commission’s written comments, memoranda, or other 47 CFR Part 1 building is closed to the general public filings in the proceeding, the presenter [MD Docket Nos. 19–105; MD Docket Nos. and until further notice, if more than may provide citations to such data or 20–105; FCC 20–64; FRS 16780] one docket or rulemaking number arguments in his or her prior comments, appears in the caption of a proceeding, memoranda, or other filings (specifying Assessment and Collection of paper filers need not submit two the relevant page and/or paragraph Regulatory Fees for Fiscal Year 2020. additional copies for each additional numbers where such data or arguments docket or rulemaking number; an can be found) in lieu of summarizing AGENCY: Federal Communications original and one copy are sufficient. them in the memorandum. Documents Commission. For detailed instructions for shown or given to Commission staff ACTION: Notice of proposed rulemaking. submitting comments and additional during ex parte meetings are deemed to be written ex parte presentations and SUMMARY: In this document, the Federal information on the rulemaking process, must be filed consistent with section Communications Commission see the SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION 1.1206(b) of the Commission’s rules. In (Commission) seeks comment on several section of this document. proceedings governed by section 1.49(f) proposals that will impact FY 2020 FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: of the Commission’s rules or for which regulatory fees. -

Publishing Blackness: Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE publishing blackness publishing blackness Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850 George Hutchinson and John K. Young, editors The University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2013 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Publishing blackness : textual constructions of race since 1850 / George Hutchinson and John Young, editiors. pages cm — (Editorial theory and literary criticism) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 472- 11863- 2 (hardback) — ISBN (invalid) 978- 0- 472- 02892- 4 (e- book) 1. American literature— African American authors— History and criticism— Theory, etc. 2. Criticism, Textual. 3. American literature— African American authors— Publishing— History. 4. Literature publishing— Political aspects— United States— History. 5. African Americans— Intellectual life. 6. African Americans in literature. I. Hutchinson, George, 1953– editor of compilation. II. Young, John K. (John Kevin), 1968– editor of compilation PS153.N5P83 2012 810.9'896073— dc23 2012042607 acknowledgments Publishing Blackness has passed through several potential versions before settling in its current form. -

Channel Guide Fusion LRG.Indd

LOCAL RADIO STATIONS 1000 HIT LIST [TVE] 1025 SWINGING STANDARDS [TVE] 1051 THE LEGENDS 1300 KPMI INCLUDED IN 1001 HIP-HOP/R&B [TVE] 1026 KIDS STUFF [TVE] 1052 1320 KOZY [TVE] PBTV EVERYWHERE 1002 JAMMIN’ [TVE] 1027 COUNTRY AMERICANA [TVE] 1054 TALK RADIO 1360 KKBJ 1003 DANCE CLUBBIN’ [TVE] 1028 HOT COUNTRY [TVE] 1055 SPORTS RADIO 1450 KBUN ITASCA, KOOCHICHING, & ST. LOUIS 1004 GROOVE [TVE] 1029 COUNTRY CLASSICS [TVE] 1059 KOJB THE EAGLE 105.3 [IKSL] 1005 THE CHILL LOUNGE [TVE] 1030 FOLK ROOTS [TVE] 1061 FM 90 KBSB COUNTIES 1006 CHRISTIAN POP & ROCK [TVE] 1031 BLUEGRASS [TVE] 1064 THE RIVER 92.1 WMIS 1007 CLASSIC R’N’B & SOUL [TVE] 1032 HOLIDAY HITS [TVE] 1066 95.5 KZY [BCH] BELTRAMI, CASS, & HUBBARD 1008 SOUL STORM [TVE] 1033 JAZZ MASTERS [TVE] 1067 96.7 KKCQ COUNTIES PBTV 1009 GOSPEL [TVE] 1034 SMOOTH JAZZ [TVE] 1068 96.9 KMFY 1010 NO FENCES [TVE] 1035 JAZZ NOW [TVE] 1070 REAL COUNTRY 98.3 WBJI MUST SUBSCRIBE TO 1011 CLASSIC ROCK [TVE] 1036 JAZZ/BLUES [TVE] 1071 99.1 Z99 [EX] PBTV EXTRA CHANNEL 1012 ALT CLASSIC ROCK [TVE] 1037 HIP HOP [TVE] 1073 KB101 CONTINUOUS COUNTRY 1013 ROCK [TVE] 1038 EASY LISTENING [TVE] 1074 MIX 103.7 KKBJ MUST SUBSCRIBE TO 1014 HEAVY METAL [TVE] 1039 THE SPA [TVE] 1075 KAXE 105.3 [SP] 1015 ALTERNATIVE [TVE] 1040 CHAMBER MUSIC [TVE] 1076 QFM KKEQ PBTV SPORTS GUIDE 1016 CLASSIC MASTERS [TVE] 1041 RITMOS LATINOS [TVE] 1077 104.5 THE BUN 2.0 1017 ADULT ALTERNATIVE [TVE] 1042 EXITOS DEL MOMENTO [TVE] 1078 J105 THE THUNDER MUST SUBSCRIBE TO 1018 POPULAR CLASSICAL [TVE] 1043 EXITOS TROPICALES [TVE] 1079 THE BRIDGE -

RIVERFRONT CIRCULATING MATERIALS (Can Be Checked Out)

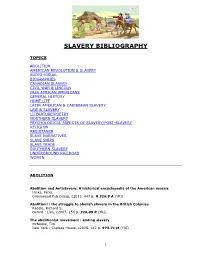

SLAVERY BIBLIOGRAPHY TOPICS ABOLITION AMERICAN REVOLUTION & SLAVERY AUDIO-VISUAL BIOGRAPHIES CANADIAN SLAVERY CIVIL WAR & LINCOLN FREE AFRICAN AMERICANS GENERAL HISTORY HOME LIFE LATIN AMERICAN & CARIBBEAN SLAVERY LAW & SLAVERY LITERATURE/POETRY NORTHERN SLAVERY PSYCHOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF SLAVERY/POST-SLAVERY RELIGION RESISTANCE SLAVE NARRATIVES SLAVE SHIPS SLAVE TRADE SOUTHERN SLAVERY UNDERGROUND RAILROAD WOMEN ABOLITION Abolition and Antislavery: A historical encyclopedia of the American mosaic Hinks, Peter. Greenwood Pub Group, c2015. 447 p. R 326.8 A (YRI) Abolition! : the struggle to abolish slavery in the British Colonies Reddie, Richard S. Oxford : Lion, c2007. 254 p. 326.09 R (YRI) The abolitionist movement : ending slavery McNeese, Tim. New York : Chelsea House, c2008. 142 p. 973.71 M (YRI) 1 The abolitionist legacy: from Reconstruction to the NAACP McPherson, James M. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, c1975. 438 p. 322.44 M (YRI) All on fire : William Lloyd Garrison and the abolition of slavery Mayer, Henry, 1941- New York : St. Martin's Press, c1998. 707 p. B GARRISON (YWI) Amazing Grace: William Wilberforce and the heroic campaign to end slavery Metaxas, Eric New York, NY : Harper, c2007. 281p. B WILBERFORCE (YRI, YWI) American to the backbone : the life of James W.C. Pennington, the fugitive slave who became one of the first black abolitionists Webber, Christopher. New York : Pegasus Books, c2011. 493 p. B PENNINGTON (YRI) The Amistad slave revolt and American abolition. Zeinert, Karen. North Haven, CT : Linnet Books, c1997. 101p. 326.09 Z (YRI, YWI) Angelina Grimke : voice of abolition. Todras, Ellen H., 1947- North Haven, Conn. : Linnet Books, c1999. 178p. YA B GRIMKE (YWI) The antislavery movement Rogers, James T. -

Cosmos: a Spacetime Odyssey (2014) Episode Scripts Based On

Cosmos: A SpaceTime Odyssey (2014) Episode Scripts Based on Cosmos: A Personal Voyage by Carl Sagan, Ann Druyan & Steven Soter Directed by Brannon Braga, Bill Pope & Ann Druyan Presented by Neil deGrasse Tyson Composer(s) Alan Silvestri Country of origin United States Original language(s) English No. of episodes 13 (List of episodes) 1 - Standing Up in the Milky Way 2 - Some of the Things That Molecules Do 3 - When Knowledge Conquered Fear 4 - A Sky Full of Ghosts 5 - Hiding In The Light 6 - Deeper, Deeper, Deeper Still 7 - The Clean Room 8 - Sisters of the Sun 9 - The Lost Worlds of Planet Earth 10 - The Electric Boy 11 - The Immortals 12 - The World Set Free 13 - Unafraid Of The Dark 1 - Standing Up in the Milky Way The cosmos is all there is, or ever was, or ever will be. Come with me. A generation ago, the astronomer Carl Sagan stood here and launched hundreds of millions of us on a great adventure: the exploration of the universe revealed by science. It's time to get going again. We're about to begin a journey that will take us from the infinitesimal to the infinite, from the dawn of time to the distant future. We'll explore galaxies and suns and worlds, surf the gravity waves of space-time, encounter beings that live in fire and ice, explore the planets of stars that never die, discover atoms as massive as suns and universes smaller than atoms. Cosmos is also a story about us. It's the saga of how wandering bands of hunters and gatherers found their way to the stars, one adventure with many heroes. -

Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 97 / Tuesday, May 20, 1997 / Notices

27662 Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 97 / Tuesday, May 20, 1997 / Notices DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE applicant. Comments must be sent to Ch. 7, Anchorage, AK, and provides the PTFP at the following address: NTIA/ only public television service to over National Telecommunications and PTFP, Room 4625, 1401 Constitution 300,000 residents of south central Information Administration Ave., N.W., Washington, D.C. 20230. Alaska. The purchase of a new earth [Docket Number: 960205021±7110±04] The Agency will incorporate all station has been necessitated by the comments from the public and any failure of the Telstar 401 satellite and RIN 0660±ZA01 replies from the applicant in the the subsequent move of Public applicant's official file. Broadcasting Service programming Public Telecommunications Facilities Alaska distribution to the Telstar 402R satellite. Program (PTFP) Because of topographical File No. 97001CRB Silakkuagvik AGENCY: National Telecommunications considerations, the latter satellite cannot Communications, Inc., KBRW±AM Post and Information Administration, be viewed from the site of Station's Office Box 109 1696 Okpik Street Commerce. KAKM±TV's present earth station. Thus, Barrow, AK 99723. Contact: Mr. a new receive site must be installed ACTION: Notice of applications received. Donovan J. Rinker, VP & General away from the station's studio location SUMMARY: The National Manager. Funds Requested: $78,262. in order for full PBS service to be Telecommunications and Information Total Project Cost: $104,500. On an restored. Administration (NTIA) previously emergency basis, to replace a transmitter File No. 97205CRB Kotzebue announced the solicitation of grant and a transmitter-return-link and to Broadcasting Inc., 396 Lagoon Drive applications for the Public purchase an automated fire suppression P.O. -

Camoflauge Discography Torrent Download Link Camoflauge Discography Torrent Download Link

camoflauge discography torrent download link Camoflauge discography torrent download link. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67e2b2492cde4eaa • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Camoflauge discography torrent download link. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67e2b2497b090621 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. -

Index of /Sites/Default/Al Direct/2008/July

AL Direct, July 2, 2008 Contents U.S. & World News ALA News Booklist Online Division News Awards Seen Online Tech Talk Publishing The e-newsletter of the American Library Association | July 2, 2008 Actions & Answers Calendar U.S. & World News Mesa board cuts librarians “It’s not over. We’re going to continue to do what we can both in Mesa and in Arizona,” Fund Our Future Arizona spokesperson Ann Ewbank told American Libraries June 27, three days after the Mesa Public School board implemented as part of its FY2008–09 budget the replacement over three years of every school library media specialist in the district with library aides. Other Arizona school systems now eyeing the cost of school library programs are the Humboldt Unified School District in Prescott Valley and the Glendale Elementary School District.... Bay County director hired after two-year hiatus After two years without a director, Bay County (Mich.) Library System has appointed Thomas H. Birch Jr. to the position, effective July 21. Birch’s appointment comes some six months after voters approved an For news of ALA Annual operating-millage renewal that was 2/10ths of a mill less than two 1- Conference, see AL mill levies that were defeated in 2006. “We’re feeling very good about Direct’s special post- moving ahead on a whole variety of things,” board Chairman Don conference issue, to be Carlyon told American Libraries.... emailed Monday, July 7. OCLC: National marketing campaign could hike funding From Awareness to Funding: A Study of Library Support in America, a new report issued by OCLC, examines the potential of a national marketing campaign to increase awareness of the value of public libraries and the need for support for libraries at local, state, and national levels.