Brief for Class Respondents ————

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Financial Abuse of Elderly People Vs. Other Forms of Elder Abuse: Assessing Their Dynamics, Risk Factors, and Society's Respon

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Financial Abuse of Elderly People vs. Other Forms of Elder Abuse: Assessing Their Dynamics, Risk Factors, and Society’s Response Author: Shelly L. Jackson, Ph.D., Thomas L. Hafemeister, J.D., Ph.D. Document No.: 233613 Date Received: February 2011 Award Number: 2006-WG-BX-0010 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Final Report Presented to the National Institute of Justice Financial Abuse of Elderly People vs. Other Forms of Elder Abuse: Assessing Their Dynamics, Risk Factors, and Society’s Response Shelly L. Jackson, Ph.D. & Thomas L. Hafemeister, J.D., Ph.D. University of Virginia Supported under award No. 2006-WG-BX-0010 from the National Institute of Justice, U.S. Department of Justice August 2010 Points of view in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the U.S. -

Elder Financial Exploitation

United States Government Accountability Office Report to the Special Committee on Aging, United States Senate December 2020 ELDER JUSTICE HHS Could Do More to Encourage State Reporting on the Costs of Financial Exploitation GAO-21-90 December 2020 ELDER JUSTICE HHS Could Do More to Encourage State Reporting on Highlights of GAO-21-90, a report to the Special Committee on Aging, United States the Costs of Financial Exploitation Senate Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found Elder financial exploitation—the Most state Adult Protective Services (APS) agencies have been providing data fraudulent or illegal use of an older on reports of abuse to the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), adult’s funds or property—has far- including data on financial exploitation, although some faced challenges reaching effects on victims and society. collecting and submitting these data. Since states began providing data to HHS’s Understanding the scope of the National Adult Maltreatment Reporting System (NAMRS) in 2017, they have problem has thus far been hindered by been voluntarily submitting more detailed data on financial exploitation and a lack of nationwide data. In 2013, perpetrators each year (see figure). However, some APS officials GAO HHS worked with states to create interviewed in selected states said collecting data is difficult, in part, because NAMRS, a voluntary system for victims are reluctant to implicate others, especially family members or other collecting APS data on elder abuse, caregivers. APS officials also said submitting data to NAMRS was challenging including financial exploitation. GAO was asked to study the extent to which initially because their data systems often did not align with NAMRS, and NAMRS provides information on elder caseworkers may not have entered data in the system correctly. -

Understanding Underreporting of Elder Financial Abuse

UNDERSTANDING UNDERREPORTING OF ELDER FINANCIAL ABUSE: CAN DATA SUPPORT THE ASSUMPTIONS? by Sheri C. Gibson B.A., University of Colorado at Colorado Springs, 2007 M.A., University of Colorado at Colorado Springs, 2009 A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Psychology 2013 iii This dissertation for the Doctor of Philosophy by Sheri C. Gibson, M.A. has been approved for the Department of Psychology by _____________________ Edith Greene, Ph.D. ____________________ Sara Honn Qualls, Ph.D. ____________________ Kelli J. Klebe, Ph.D. ____________________ Tom Pyszczynski, Ph.D. ____________________ Valerie Stone, Ph.D. iv Gibson, Sheri C., M.A., Psychology Understanding Underreporting of Elder Abuse: Can Data Support the Assumptions? Dissertation directed by Edith Greene, Ph.D. The fastest growing segment of the U.S. population is adults ages 60 and older. Subsequently, cases of elder abuse are on the rise with the most common form being financial victimization. Approximately only one in five cases of elder financial abuse (EFA) are reported to authorities. The present study used vignette methodology to determine 1) under what circumstances cognitively-intact older adults would report EFA, 2) to whom they would report, 3) what impediments prevent them from reporting, and 4) how their willingness to report is influenced by age-related self-perceptions and attitudes about aging. Two important factors that influenced reporting behavior emerged from the findings: the quality of the relationship between the victim and alleged offender; and age-related stereotypes. -

THE TRUTH ABOUT ELDER ABUSE What You Need to Know to Protect Yourself and Your Loved Ones

THE TRUTH ABOUT ELDER ABUSE What You Need to Know to Protect Yourself and Your Loved Ones © AMERICAN ACADEMY OF ESTATE PLANNING ATTORNEYS, INC. The Truth About Elder Abuse 1 THE TRUTH ABOUT ELDER ABUSE: WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW TO PROTECT YOURSELF AND YOUR LOVED ONES Imagine this: You are physically frail, and you have to rely on other people for help with the most basic daily tasks. You need assistance getting out of bed in the morning, bathing and getting yourself dressed, preparing meals, and getting out of the house to go grocery shopping or to visit friends. On top of this, your memory isn’t what it used to be. You have trouble recalling recent events and your math skills are starting to slip. Now, imagine that the person you rely on for help is systematically stealing your money, threatening and screaming at you, or even physically assaulting you. This may be your child, your spouse, or your paid caregiver. You don’t know where to turn for help, and you’re not sure you have the words to express what is happening to you, anyway. You feel alone, helpless, and in despair. For too many senior citizens, this is a daily reality. Elder abuse is a quiet but growing epidemic. The National Center on Elder Abuse reports that millions of seniors are abused each year.1 It is difficult to come up with an accurate figure, because only a fraction of victims report their abuse. It is believed that incidents of elder abuse are severely underreported to adult protective services, and only about 1 in 14 are brought to the attention of authorities.2 This means we need to educate ourselves about elder abuse and be watchful in protecting our loved ones and ourselves. -

What Is Elder Abuse?

ELDER JUSTICE NAVIGATOR PROJECT ELDER ABUSE DESK GUIDE FOR JUDGES AND COURT STAFF By Nicole K. Parshall, Esq. And Kayleah M. Feser, MSW Center for Elder Law and Justice June 2018 This Desk Guide was supported, in part, by a grant (No. 90EJIG0011-01-00) from the Administration for Community Living (ACL), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). Grantees carrying out projects under government sponsorship are encouraged to express freely their findings and conclusions. Therefore, points of view or opinions do not necessarily represent official ACL or DHHS policy. 1 Parts of this desk guide were adapted from the American Bar Association Commission on Legal Problems of the Elderly publication entitled “Elder Abuse Cases in the State Courts – Three Curricula for Judges and Court Staff.” This publication was developed under the leadership of the American Bar Association Commission on Legal Problems of the Elderly and the National Association of Women Judges, and was authored by Lori A. Stiegel, J.D., Associate Staff Director of the Commission. These curricula and materials were made possible by Grant No. SJI- 93-12J-E-274-P96-1 from the State Justice Institute. Copyright © 1997 American Bar Association. Reprinted by permission. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………….6 HOW TO USE THIS MANUAL AND THE NAVIGATOR PROJECT…………8 REFERRAL PROCESS…………………………………………….8 INTAKE…………………………………………………………..9 SERVICES………………………………………………………..10 EMERGENT SITUATIONS………………………………………...11 DATA COLLECTION……………………………………………..11 CONTACT INFORMATION……………………………………….12 -

2011 National Crime Victims' Rights Week Resource Guide

At A GlAnce Introduction – Section 5: Landmarks in Victims’ Rights and 2011 national crime Victims’ Rights Week Services Resource Guide – Section 6: Statistical Overviews Dates: Sunday, April 10 – Saturday, April 16, 2011 – Section 7: Additional Resources Theme: “Reshaping the Future, Honoring the Past” Colors:* Teal: C=100, M=8, Y=35, K=35 • DVD: The enclosed 5-minute theme video features Yellow: C=0, M=12, Y=100, K=0 interviews with criminal justice personnel, advocates, Black: C=0, M=0, Y=0, K=100 and victims whose reflections honor the progress of the Fonts: Garamond (body text) victims’ rights field and present a provocative look at Gotham Ultra and Cactus Bold (artwork) issues that lay ahead. This Year’s Format Quick Planning tips As in years past, you will find a wide range of instructional ma- • Review all the contents of the Resource Guide before terials, updated statistics, and promotional items in the 2011 moving forward. NCVRW Resource Guide. Please note that the entire contents • Establish a planning committee to help share the work- of the Resource Guide may be found on the enclosed CD- load and tap into even more ideas. ROM. Peruse this wealth of information from your computer or print any materials you would like to distribute. • Develop a timetable detailing all activities and assign- ments leading up to your event(s). Hard copies of all NCVRW-related public awareness artwork and the popular public awareness posters are included in the • Decide what Resource Guide artwork and information mailed version of the Resource Guide. And, as in past years, you want to use and what other materials you might anyone who receives the Resource Guide will also receive the need to develop. -

Elder Abuse: Awareness & Prevention “Elder Abuse Damages Public Health and Threatens Millions of Our Parents, Grandparents, and Friends

Elder Abuse: Awareness & Prevention “Elder abuse damages public health and threatens millions of our parents, grandparents, and friends. It is a crisis that knows no borders or socio-economic lines” President Barack Obama Proclamation- June 11, 2014 Presented by: Holland Police Department 27 Sturbridge Rd Holland, MA 01521 [email protected] What is Elder Abuse? Physical, emotional, & sexual abuse, as well as exploitation, neglect, and abandonment of a person 60 yrs of age or over. Emotional abuse: Verbal assaults, threats of abuse, harassment, or intimidation. Confinement: Restraining or isolating [other than for medical reasons] Passive Neglect: Caregiver’s failure to provide the person with life’s necessities, including, but not limited to, food, clothing, shelter, & medical care. Willful Deprivation: Denying medication, medical care, shelter, food, a therapeutic device, or other physical assistance, and exposing that person to the risk of physical, mental, or emotional harm [except when the older, competent adult has expressed a desire to go without such care] Financial Exploitation: The misuse or withholding of resources by another. MGL Definitions: Elder Abuse Department of Elder Affairs c19A s14 Elderly Person- 60 yrs of age or over [is considered an “Elderly Person” in Massachusetts]. Abuse- An act or omission which results in serious physical or emotional injury to an elderly person or financial exploitation of an elderly person. [Includes Assault] Financial Exploitation- An act or omission by another person, which causes a substantial monetary or property loss to an elderly person, or causes a substantial monetary or property gain to the other person. Assault vs. Assault & Battery Assault- Attempting to use physical force against another, or demonstrating an intention to use immediate force against another. -

Silversneakers Class at L.A

The FREE IN FOCUS FOR PEOPLE OVER 50 VOL.31, NO.6 More than 200,000 readers throughout Greater Washington JUNE 2019 Get fit for free if 65 or better INSIDE… By Michael Doan PHOTO BY MICHAEL DOAN You’d never mistake Dottie Longo for a Marine drill sergeant. The 67-year-old fitness instructor encourages her students, includ- ing me, with phrases like “if you can,” “at your own level” and “don’t overdo it.” No one is ever asked to “go for the burn.” In a recent class, Longo announced, “I’m doing eight repetitions with my two-and-a- half-pound weights. You can use a lighter LEISURE & TRAVEL weight — or none at all — if you’d like.” Sun and fun in Miami’s funky So we go at our own pace in my eight-per- son SilverSneakers class at L.A. Fitness in Art Deco district; plus, a hik- the Crystal City neighborhood of Arlington, ing pilgrimage through Tus- Virginia. Some of us even sing along to the cany, and how to factor “daily ‘60s and ‘70s music during the one-hour, overhead” into vacation costs twice-a-week class for people 65 and over. page 36 “A lot of seniors are intimidated by gyms © MARIA KROVATIN — the layout and all the fitness equipment,” Longo said. “Our SilverSneakers class pro- vides them a certain amount of comfort at their particular skill level. That’s my job.” A national program SilverSneakers is part of a 27-year-old program administered by Tivity Health. Currently, the program can be accessed at 16,000 gyms nationwide. -

The Prosecutor's Resource

Elder Abuse Current as of April 2017 Issue #18 | May 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .....................................................................................................................................................................4 Part One: Overview of Elder Abuse ...........................................................................................................................5 .................................................................................................................................................................................................................5 ..........................................................................................................................................................................................................6 A. Defining Elder Abuse ...........................................................................................................................................................................................7 1. Financial Exploitation 2. Settings Where Abuse Occurs .............................................................................................................................................................................8 B. Characteristics of Elder Abuse Victims ................................................................................................................................................................11 C. Characteristics of ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................ -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 117 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 117 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 167 WASHINGTON, MONDAY, APRIL 19, 2021 No. 67 House of Representatives The House met at noon and was As we know all too well in rural dispense with the political games. We called to order by the Speaker pro tem- Pennsylvania, infrastructure has real- need roads, bridges, and reliable inter- pore (Mrs. DINGELL). life consequences for communities. At net. We do not need the Green New f its core, improving roads, bridges, and Deal. Stop calling this infrastructure. other key infrastructure should be a Stop hiding progressive policies in tro- DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO commonsense, bipartisan priority. jan horses. Stop trying to trick the TEMPORE Failing infrastructure does not dis- American people. The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- criminate. A broken bridge can harm While I stand ready to work with the fore the House the following commu- Democrats just as it can harm Repub- President and House Democrats on nication from the Speaker: licans. what is true infrastructure reform, this WASHINGTON, DC, Unfortunately, the so-called infra- plan is further evidence that the Biden- April 19, 2021. structure reform put forth by Presi- Harris administration are more happy I hereby appoint the Honorable DEBBIE dent Biden fails to take seriously the to push their radical agenda at the ex- DINGELL to act as Speaker pro tempore on challenges that we are currently facing pense of hardworking Americans. this day. in Pennsylvania and around the entire Instead of propelling these radical NANCY PELOSI, Speaker of the House of Representatives. -

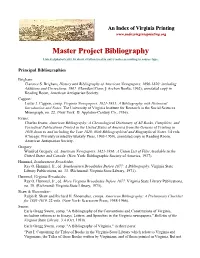

M Master R Proje Ect Bib Bliogr Raphy

An Index of Virginia Printing www.indexvirginiaprinting.org Master Project Bibliography Listed alphabetically by short citation used in entrry notes according to source type. Principal Bibliographies Brigham: Clarence S. Brigham, History and Bibliography of American Newsppapers, 16900-1820: including Additions and Corrections, 1961. (Hamden [Conn.]: Archon Books, 1962); annotated copy in Reading Room, American Antiquarian Society. Cappon: Lester J. Cappon, comp. Virginia Newspapers, 1821-1935: A Biblioggraphy with Historical Introduction and Notes. The University of Virginia Institute for Research in the Social Sciences Monograph, no. 22. (New York: D. Appleton-Century Co., 1936). Evans: Charles Evans, American Bibliography: A Chronological Dictionary of All Books, Pamphlets, and Periodical Publications Printed in the United States of America from the Genesis of Printing in 1639 down to and including the Year 1820: With Bibliographical and Biographical Notes. 14 vols. (Chicago: Privately printed by Blakely Press, 1903-1959), annotated copy in Reading Room, American Antiquarian Society. Gregory: Winifred Gregory, ed. American Newspapers, 1821-1936: A Union List of Files Available in the United States and Canada. (New York: Bibliographic Society of America, 1937). Hummel, Southeastern Broadsides. Ray O. Hummel, Jr., ed. Southeastern Broadsides Before 1877: A Bibliography. Virginia State Library Publications, no. 33. (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1971). Hummel, Virginia Broadsides. Ray O. Hummel, Jr., ed. More ViV rginia Broadsides Beforre 1877. Virginia State Library Publications, no. 39. (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1975). Shaw & Shoemaker: Ralph R. Shaw and Richard H. Shoemaker, comps. American Bibliography: A Preliminary Checklist for 1801-1819. 22 vols. (New York: Scarecrow Press, 1958-1966). Swem: Earle Gregg Swem, comp. -

The Supreme Court 2018‐2019 Topic Proposal

The Supreme Court 2018‐2019 Topic Proposal Proposed to The NFHS Debate Topic Selection Committee August 2017 Proposed by: Dustin L. Rimmey Topeka High School Topeka, KS Page 1 of 1 Introduction Alexander Hamilton famously noted in the Federalist no. 78 “The Judiciary, on the contrary, has no influence over either the sword or the purse; no direction of either of the strength or of the wealth of the society; and can take no active resolution whatever.” However, Hamilton could be no further from the truth. From the first decision in 1793 up to the most recent decision the Supreme Court of the United States has had a profound impact on the Constitution. Precedents created by Supreme Court decisions function as one of the most powerful governmental actions. Jonathan Bailey argues “those in the legal field treat Supreme Court decisions with a near‐religious reverence. They are relatively rare decisions passed down from on high that change the rules for everyone all across the country. They can bring clarity, major changes and new opportunities” (Bailey). For all of the power and awe that comes with the Supreme Court, Americans have little to know accurate knowledge about the land’s highest court. According to a 2015 survey released by the Annenberg Public Policy Center: 32% of Americans could not identify the Supreme Court as one of our three branches of government, 28% believe that Congress has full review over all Supreme Court decisions, and 25% believe the court could be eliminated entirely if it made too few popular decisions. Because so few Americans lack solid understanding of how the Supreme Court operates, now is the perfect time for our students to actively focus on the Supreme Court in their debate rounds.