A Decade of REDD+ in a Changing Political Environment in the Democratic Republic of Congo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tangled! Congolese Provincial Elites in a Web of Patronage

Researching livelihoods and services affected by conflict Tangled! Congolese provincial elites in a web of patronage Working paper 64 Lisa Jené and Pierre Englebert January 2019 Written by Lisa Jené and Pierre Englebert SLRC publications present information, analysis and key policy recommendations on issues relating to livelihoods, basic services and social protection in conflict-affected situations. This and other SLRC publications are available from www.securelivelihoods.org. Funded by UK aid from the UK Government, Irish Aid and the EC. Disclaimer: The views presented in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the UK Government’s official policies or represent the views of Irish Aid, the EC, SLRC or our partners. ©SLRC 2018. Readers are encouraged to quote or reproduce material from SLRC for their own publications. As copyright holder SLRC requests due acknowledgement. Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium Overseas Development Institute (ODI) 203 Blackfriars Road London SE1 8NJ United Kingdom T +44 (0)20 3817 0031 F +44 (0)20 7922 0399 E [email protected] www.securelivelihoods.org @SLRCtweet Cover photo: Provincial Assembly, Lualaba. Lisa Jené, 2018 (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0). B About us The Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium (SLRC) is a global research programme exploring basic services, livelihoods and social protection in fragile and conflict-affected situations. Funded by UK Aid from the UK Government’s Department for International Development (DFID), with complementary funding from Irish Aid and the European Commission (EC), SLRC was established in 2011 with the aim of strengthening the evidence base and informing policy and practice around livelihoods and services in conflict. -

Democratic Republic of Congo Constitution

THE CONSTITUTION OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO, 2005 [1] Table of Contents PREAMBLE TITLE I GENERAL PROVISIONS Chapter 1 The State and Sovereignty Chapter 2 Nationality TITLE II HUMAN RIGHTS, FUNDAMENTAL LIBERTIES AND THE DUTIES OF THE CITIZEN AND THE STATE Chapter 1 Civil and Political Rights Chapter 2 Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Chapter 3 Collective Rights Chapter 4 The Duties of the Citizen TITLE III THE ORGANIZATION AND THE EXERCISE OF POWER Chapter 1 The Institutions of the Republic TITLE IV THE PROVINCES Chapter 1 The Provincial Institutions Chapter 2 The Distribution of Competences Between the Central Authority and the Provinces Chapter 3 Customary Authority TITLE V THE ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COUNCIL TITLE VI DEMOCRACY-SUPPORTING INSTITUTIONS Chapter 1 The Independent National Electoral Commission Chapter 2 The High Council for Audiovisual Media and Communication TITLE VII INTERNATIONAL TREATIES AND AGREEMENTS TITLE VIII THE REVISION OF THE CONSTITUTION TITLE IX TRANSITORY AND FINAL PROVISIONS PREAMBLE We, the Congolese People, United by destiny and history around the noble ideas of liberty, fraternity, solidarity, justice, peace and work; Driven by our common will to build in the heart of Africa a State under the rule of law and a powerful and prosperous Nation based on a real political, economic, social and cultural democracy; Considering that injustice and its corollaries, impunity, nepotism, regionalism, tribalism, clan rule and patronage are, due to their manifold vices, at the origin of the general decline -

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS for the DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC of the CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS FOR THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20 BAS-UELE HAUT-UELE ITURI S O U T H S U D A N COUNTRYWIDE NORTH KIVU OCHA IMA World Health Samaritan’s Purse AIRD Internews CARE C.A.R. Samaritan’s Purse Samaritan’s Purse IMA World Health IOM UNHAS CAMEROON DCA ACTED WFP INSO Medair FHI 360 UNICEF Samaritan’s Purse Mercy Corps IMA World Health NRC NORD-UBANGI IMC UNICEF Gbadolite Oxfam ACTED INSO NORD-UBANGI Samaritan’s WFP WFP Gemena BAS-UELE Internews HAUT-UELE Purse ICRC Buta SCF IOM SUD-UBANGI SUD-UBANGI UNHAS MONGALA Isiro Tearfund IRC WFP Lisala ACF Medair UNHCR MONGALA ITURI U Bunia Mercy Corps Mercy Corps IMA World Health G A EQUATEUR Samaritan’s NRC EQUATEUR Kisangani N Purse WFP D WFPaa Oxfam Boende A REPUBLIC OF Mbandaka TSHOPO Samaritan’s ATLANTIC NORTH GABON THE CONGO TSHUAPA Purse TSHOPO KIVU Lake OCEAN Tearfund IMA World Health Goma Victoria Inongo WHH Samaritan’s Purse RWANDA Mercy Corps BURUNDI Samaritan’s Purse MAI-NDOMBE Kindu Bukavu Samaritan’s Purse PROGRAM KEY KINSHASA SOUTH MANIEMA SANKURU MANIEMA KIVU WFP USAID/BHA Non-Food Assistance* WFP ACTED USAID/BHA Food Assistance** SA ! A IMA World Health TA N Z A N I A Kinshasa SH State/PRM KIN KASAÏ Lusambo KWILU Oxfam Kenge TANGANYIKA Agriculture and Food Security KONGO CENTRAL Kananga ACTED CRS Cash Transfers For Food Matadi LOMAMI Kalemie KASAÏ- Kabinda WFP Concern Economic Recovery and Market Tshikapa ORIENTAL Systems KWANGO Mbuji T IMA World Health KWANGO Mayi TANGANYIKA a KASAÏ- n Food Vouchers g WFP a n IMC CENTRAL y i k -

UNJHRO) MONUSCO – OHCHR March 2021 REPORTED HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS in DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC of the CONGO (DRC)

Protection of civilians: Human rights violations documented in provinces affected by conflict United Nations Joint Human Rights Office in the DRC (UNJHRO) MONUSCO – OHCHR March 2021 REPORTED HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO (DRC) Figure 1. Percentage of violations per territory Figure 2. Number of violations per province in DRC SOUTH CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC SUDAN North Kivu Tanganyika Bas-Uele Haut-Uele Masisi 79% 21 Kalemie 36% 65 North-Ubangi Beni 64 36 Manono0 100 2 UGANDA CAMEROON South-Ubangi Rutshuru 69 31 Moba0 100 Ituri Mongala Lubero 29 71 77 Nyiragongo 86 14 Maniema Tshopo Walikale 90 10 Kabambare 63% 395 CONGO Equateur North Butembo0 100 Kasongo0 100 Kivu Kibombo0 100 GABON Tshuapa 359 South Kivu RWANDA Kasai Shabunda 82% 18 Mai-Ndombe Kamonia (Kas.)0 100% Kinshasa Uvira 33 67 5 BURUNDI Llebo (Kas.)0 100 Sankuru 15 63 Fizi 33 67 Kasai South Tshikapa (Kas.)0 100 Maniema Kivu Kabare 100 0 Luebo (Kas.)0 100 Kwilu 23 TANZANIA Walungu 29 71 Kananga (Kas. C)0 100 Lomami Bukavu0 100 22 4 Demba (Kas. C)0 100 Kongo 46 Mwenga 67 33 Central Luiza (Kas. C)0 100 Kwango Tanganyika Kalehe0 100 Kasai Dimbelenge (Kas. C)0 100 Central Haut-Lomami Ituri Miabi (Kas. O)0 100 Kasai 0 100 ANGOLA Oriental Irumu 88% 12 Mbuji-Mayi (Kas. O) Haut- Djugu 64 36 Lualaba Bas-Uele Katanga Mambasa 30 70 Buta0 100% Mahagi 100 0 % by armed groups % by State agents The boundaries and names shown and designations ZAMBIA used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

Review of the National Program for Onchocerciasis Control in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease Review Review of the National Program for Onchocerciasis Control in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Jean-Claude Makenga Bof 1,* , Fortunat Ntumba Tshitoka 2, Daniel Muteba 2, Paul Mansiangi 3 and Yves Coppieters 1 1 Ecole de Santé Publique, Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB), Route de Lennik 808, 1070 Brussels, Belgium; [email protected] 2 Ministry of Health: Program of Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTD) for Preventive Chemotherapy (PC), Gombe, Kinshasa, DRC; [email protected] (F.N.T.); [email protected] (D.M.) 3 Faculty of Medicine, School of Public Health, University of Kinshasa (UNIKIN), Lemba, Kinshasa, DRC; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +32-493-93-96-35 Received: 3 May 2019; Accepted: 30 May 2019; Published: 13 June 2019 Abstract: Here, we review all data available at the Ministry of Public Health in order to describe the history of the National Program for Onchocerciasis Control (NPOC) in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Discovered in 1903, the disease is endemic in all provinces. Ivermectin was introduced in 1987 as clinical treatment, then as mass treatment in 1989. Created in 1996, the NPOC is based on community-directed treatment with ivermectin (CDTI). In 1999, rapid epidemiological mapping for onchocerciasis surveys were launched to determine the mass treatment areas called “CDTI Projects”. CDTI started in 2001 and certain projects were stopped in 2005 following the occurrence of serious adverse events. Surveys coupled with rapid assessment procedures for loiasis and onchocerciasis rapid epidemiological assessment were launched to identify the areas of treatment for onchocerciasis and loiasis. -

UNJHRO) MONUSCO – OHCHR July 2020 REPORTED HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS in DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC of the CONGO (DRC)

Protection of civilians: Human rights violations documented in provinces affected by conflict United Nations Joint Human Rights Office in the DRC (UNJHRO) MONUSCO – OHCHR July 2020 REPORTED HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO (DRC) Figure 1. Percentage of violations per territory Figure 2. Number of violations per province in DRC SOUTH North Kivu Kasai CAR SUDAN Masisi 93% 7% Demba (Kas. C) 100% Nyiragongo 84% 16% Dibaya (Kas. C) 100% Bas-Uele Haut-Uele North-Ubangi Beni 79% 21% Kananga (Kas.C) 100% UGANDA CAMEROON South-Ubangi Rutshuru 88% 12% Kazumba (Kas. C) 100% Mongala Lubero 40% 60% Dimbelenge (Kas.C) 100% 95 Tshikapa (Kas.) 100% Ituri Walikale 76% 24% Tshopo CONGO Equateur Goma 100% Kamonia (Kas.) 100% North Kivu Butembo 100% Ilebo (Kas.) 100% GABON Tshuapa 383 Luebo (Kas.) 100% South Kivu RWANDA Mweka (Kas.) 100% Mwenga 60% 40% Mai-Ndombe Uvira 33% 67% Tshilenge (Kas. O) 100% Kinshasa BURUNDI Kasai Sankuru 25 51 Kalehe 71% 29% Mbuji-Mayi (Kas. O) 100% South Bukavu 100% Miabi (Kas. O) 100% Maniema Kivu TANZANIA Fizi 40% 60% Maniema Kwilu 27 Lomami 100% Kabambare 39 Shabunda 44% 56% Kongo 15 59 Walungu 100% Kindu 100% Central Kwango Tanganyika 100%Ituri Kasongo Kasai 100% Central Walungu 100% Haut-Lomami Djugu 38% 62% 100% Tanganyika Kasai Irumu 100% Kalemie 16% 100% 84% ANGOLA Oriental Mahagi 100% 100% Nyunzu 70% 100% 30% Lualaba Haut- Aru Katanga 100% Moba 100%100% Mambasa 100% Manono 100% Bunia 100% Kabalo 100% The boundaries and names shown and designations ZAMBIA % by State agents used on this map do not imply official endorsement % by armed groups or acceptance by the United Nations. -

PIREDD Mongala République Démocratique Du Congo

PIREDD Mongala République Démocratique du Congo RDC182081T Enabel • Agence belge de développement • Société anonyme de droit public à finalité sociale 1 Rue Haute 147 • 1000 Bruxelles • T +32 (0)2 505 37 00 • enabel.be Organisation(s) Participante(s) Objectif Spécifique du Fonds Agence Belge de Développement Enabel Projet Intégré REDD+ Mongala Chef(s) de file gouvernemental (le Chef de programme : cas échéant) : Nom : Nom : Téléphone : Téléphone : E-mail : E-mail : Numéro du programme : Programme Intégré REDD+ de la Mongala (PIREDD Mongala) Coûts du programme : Lieu du programme : Fonds : 7 M USD Province de la Mongala Variante proposée : à 12 M USD 5 zones d’intervention réparties dans les 3 Territoires : Bumba : 2 Lisala : 2 Bongandanga : 1 Organisations Participantes : Durée du programme : Durée totale (en mois) : 48 mois en deux phases de 24 mois Enabel Date de commencement prévue1 : juin 2019 1 La date de commencement officielle de tout programme REDD+ approuvé correspond au transfert de fonds par le Bureau MPTF. 2 Table des matières Acronymes ................................................................................................................................ 6 1 Préambule ....................................................................................................................... 7 2 Résume exécutif de l’Action ............................................................................................. 7 3 Contexte de l’Action ....................................................................................................... -

Province De L'equateur Profil Resume Pauvrete Et

Programme des nations unies pour le développement Unité de lutte contre la pauvreté RDC PROVINCE DE L’EQUATEUR PROFIL RESUME PAUVRETE ET CONDITIONS DE VIE DES MENAGES Mars 2009 - 1 – Province de L’Equateur Sommaire PROVINCE DE L’EQUATEUR Province Equateur Avant-propos..............................................................3 Superficie 403.292km² 1 – Présentation générale de l’Equateur....................4 Population 2005 5,8 millions 2 – La pauvreté dans l’Equateur ................................6 Densité 14 hab/km² Nb de communes 7 3 – L’éducation.........................................................10 Nb de territoires 8 4 – Le développement socio-économique des Routes d’intérêt national 2.939 km femmes.....................................................................11 Routes d’intérêt provincial 2.716 km 5 – La malnutrition et la mortalité infantile ...............12 Routes secondaires 3.158 km 6 – La santé maternelle............................................13 Réseau ferroviaire 187 km 7 – Le sida et le paludisme ......................................14 Gestion de la province Gouvernement Provincial 8 – L’habitat, l’eau et l’assainissement ....................15 Nb de ministres provinciaux 10 9 – Le développement communautaire et l’appui des Nb de députés provinciaux 108 Partenaires Techniques et Financiers (PTF) ...........16 - 2 – Province de L’Equateur Avant-propos Le présent rapport présente une analyse succincte des conditions de vie des ménages de la province de l’Equateur. L’analyse se base essentiellement sur les récentes enquêtes statistiques menées en RDC. Il fait partie d’une série de documents sur les conditions de vie de la population des 11 provinces de la RDC. Cette série de rapports constitue une analyse réalisée en toute indépendance par des experts statisticiens-économistes, afin de fournir une vision objective de la réalité de chaque province en se basant sur les principaux indicateurs de pauvreté et conditions de vie de la population, spécialement ceux se rapportant aux OMD et à la stratégie de réduction de la pauvreté. -

UNHCR DRC SITUATION Jun

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO DRC SITUATION As of 30 June 2021 536,419 REFUGEES FROM DRC IN AFRICA TOTAL NUMBER OF REFUGEES AND ASYLUM SEEKERS KEY STATISTICS REFUGEE POPULATION BY COUNTRY OF ORIGIN 942,143 AGE AND GENDER BREAKDOWN CAR 221,694 TOTAL DRC REFUGEE POPULATION Uganda 432,390 62.39% or 334,675 Children Rwanda 213,465 Southern Africa 2 121,196 55,819 96.7% 19.39% or 104,011 Women S. Sudan REFUGEES Burundi 79,662 or 84,745 Men Burundi 44,066 519,819 15.80% Tanzania 79,002 or 12,988 Elderly Rep. Congo 670 2.42% Rwanda 74,836 Angola 440 Zambia 58,136 3.1 % 1 ASYLUM SEEKERS Others 147 Other countries 3 53,078 16,600 Somalia 111 Angola 23,472 TYPES OF LOCATION Republic of Congo 20,371 Sudan 41 Source: UNHCR 24. 5% 74. 1% 1.4% Uganda 26 2 Southern Africa includes Namibia, Botswana, Lesotho, Malawi, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Madagascar, South Africa and the Kingdom of Eswatini. 131,456 397,683 7,280 1 Others include Ivory Coast, Eritrea, Syria, Liberia, Chad, etc. Source: UNHCR 3 Other countries include South Sudan, Kenya, Central African Republic and Chad. Camps and settlements Outside camp/settlements Urban areas CENTRAL AFRICAN SOUTH SUDAN REPUBLIC Bili #B Gbadolite "Û 2 Kilos Bili A E#B E Mboti Mole #B Yakoma Molegbe Û #B Inke E" Kaka C#Meri #B C# Faradje Boyabu 76 Modale C# Libenge NORD-UBANGI BAS-UELE Bele HAUT-UELE SUD-UBANGI Biringi 7 C# A CAMEROON 294 Aru 11 C#C# MONGALA C#C# C# C#C#C#C# C#C# ITURI C#C#C# Bunia C# 422 231 Beni 463 REPUBLIC EQUATEUR UGANDA 3 268 GABON OF CONGO TSHOPO TSHUAPA NORD-KIVU C#C#C#C# C#C#C C# C# 3 C# -

Evaluation of Democratic Republic of the Congo Interim Country Strategic Plan 2018-2020

Evaluation of Democratic Republic of the Congo Interim Country Strategic Plan 2018-2020 Evaluation Report: Volume I Commissioned by the WFP Office of Evaluation October 2020 Acknowledgements The external evaluation team is very grateful for all the assistance provided by Michael Carbon, evaluation manager, and Lia Carboni, research analyst, of the WFP Office of Evaluation (OEV); Claude Jibidar, Country Director of WFP Democratic Republic of the Congo; their many colleagues at headquarters (HQ), regional bureau (RB), country office (CO) and sub-offices. Assistance from the evaluation focal point in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Tafadzwa Chiposi was invaluable. We also acknowledge with thanks the contribution of the numerous government, multilateral, bilateral, and non-governmental organization informants who gave generously their time and advice during the evaluation process. We would also like to extend our thanks to Clemence Bouchat and James Hunter at Action Against Hunger (ACF) UK for their vital work. Disclaimer The opinions expressed are those of the evaluation team, and do not necessarily reflect those of the World Food Programme. Responsibility for the opinions expressed in this report rests solely with the authors. Publication of this document does not imply endorsement by WFP of the opinions expressed. The designations employed and the presentation of material in the maps do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WFP concerning the legal or constitutional status of any country, territory or sea area, or concerning the delimitation of frontiers. Key personnel for the evaluation OFFICE OF EVALUATION Andrea Cook – Director of Evaluation Michael Carbon – Evaluation Manager Lia Carboni – Evaluation Analyst EXTERNAL EVALUATION TEAM Dr. -

Dossier Technique Et Financier

DOSSIER TECHNIQUE ET FINANCIER PROGRAMME D'APPUI À L’ENSEIGNEMENT TECHNIQUE ET À LA FORMATION PROFESSIONNELLE (ETFP) DANS LES DISTRICTS DE LA MONGALA ET DU SUD UBANGI EN EQUATEUR (EDU-EQUA) REPUPLIQUE DEMOCRATIQUE DU CONGO CODE DGD : NN 3013837 CODE NAVISION : RDC 12 175 11 TABLE DES MATIÈRES ABRÉVIATIONS .......................................................................................................................................4 RÉSUMÉ ..................................................................................................................................................6 FICHE ANALYTIQUE DE L’INTERVENTION ..........................................................................................7 1 ANALYSE DE LA SITUATION .........................................................................................................9 1.1 SITUATION AU NIVEAU NATIONAL ......................................................................................................................... 9 1.2 SITUATION AU NIVEAU PROVINCIAL ..................................................................................................................... 18 1.3 CONCLUSIONS SUR LA SITUATION DU SECTEUR ETFP DANS LES 2 DISTRICTS CONCERNÉS AU MOMENT DE LA MISSION DE FORMULATION ........................................................................................................................................................... 31 2 ORIENTATIONS STRATÉGIQUES .............................................................................................. -

Drc Hno-Hrp 2021 at a Glance.Pdf

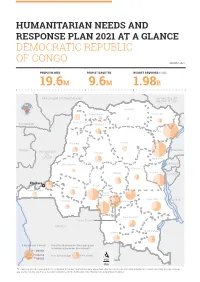

HUMANITARIAN NEEDS AND RESPONSE PLAN 2021 AT A GLANCE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO JANUARY 2021 PEOPLE IN NEED PEOPLE TARGETED BUDGET REQUIRED (USD) 19.6M 9.6M 1.98B RÉPUBLIQUE CENTRAFRICAINE RÉPUBLIQUE DU SOUDAN DU SUD Bas-Uele Nord-Ubangi Haut-Uele Sud-Ubangi CAMEROUN Mongala Ituri Equateur Tshopo GABON OUGANDA RÉPUBLIQUE Tshuapa DU CONGO Nord-Kivu Maï-Ndombe RWANDA Maniema Sud-Kivu Sankuru BURUNDI insasa Kasaï Kwilu Kongo-Central Kasaï- Central Tanganyika TANZANIE Kwango Lomami Haut-Lomami Kasaï- Oriental ANGOLA Haut-Katanga Lualaba # de pers.dans le besoin Proportion de personnes ciblées par rapport au nombre de personnes dans le besoin 1 000 000 500 000 Pers. dans le besoin Pers. ciblées O 100 000 100 Km The names used in the report and the presentation of the various media do not imply any opinion whatsover on the part of the United Nations Secretariat concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of their authorities, nor the delimitation of its boundaries or geographical boundaries. ZAMBIE HUMANITARIAN NEEDS AND RESPONSE PLAN 2020 AT A GLANCE Severity of needs INTERSECTORAL SEVERITY OF NEEDS (2021) MINOR MODERATE STRICT CRITICAL CATASTROPHIC 11% 17% 44% 24% 4% CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN CAMEROON Nord-Ubangi Sud-Ubangi Haut-Uele Bas-Uele Mongala Ituri Equateur Tshopo REPUBLIC OF Tshuapa OUGANDA CONGO GABON Nord-Kivu RWANDA Maï-Ndombe Maniema Sud-Kivu BURUNDI Kinshasa Sankuru !^ Kwilu Kasaï Kongo-Central Lomami Kasaï- TANZANIA Central Tanganyika Kwango Kasaï- Oriental Haut-Lomami Haut-Katanga Lualaba ANGOLA Severity of needs O Catastrophic Critical 100 Strict Km ZAMBIA Moderate Minor None The designations employed in the report and the presentation of the various materials do not imply any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of countries, territories, cities or areas, or of their authorities, nor of the delimitation of its frontiers or geographical limits.