Tangled! Congolese Provincial Elites in a Web of Patronage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WEEKLY BULLETIN on OUTBREAKS and OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 38: 15 - 21 September 2018 Data As Reported by 17:00; 21 September 2018

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 38: 15 - 21 September 2018 Data as reported by 17:00; 21 September 2018 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 2 52 43 11 New events Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises Algeria 217 2 1 220 0 Mali 224 35 3 403 67 Niger 2 734 78 Sierra léone Chad 2 337 18 2 0 1 643 11 Guinea 3 062 Nigeria South Sudan 507 142 Liberia 2 837 51 36 0 Central African Ethiopia 127 0 2 663 1 49 13 Cameroon Republic 132 0 4 139 116 40 1 13 529 100 310 27 3 669 16 Democratic Republic Uganda Kenya 7 2 Sao Tome of Congo 1 0 Congo 95 11 Legend & Principe 23 8 5 0 381 1 1 0 147 99 Measles Humanitarian crisis 18 780 623 2 883 23 979 273 Seychelles Necrotising cellulitis/fasciitis Tanzania Monkeypox 22 22 2 829 57 5 813 0 Acute watery diarrhoea Lassa fever 37 0 3 739 68 Cholera Yellow fever Rift Valley fever Dengue fever Angola Typhoid fever Hepatitis E 954 19 1 Zambia Ebola virus disease 2 663 1 Plague Rabies Guinea Worm Zimbabwe Namibia Madagascar Mauritius Severe Acute Malnutrition cVDPV 1 983 8 5 891 38 899 3 Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever 15 5 Floods 2 554 24 Cases Countries reported in the document N Deaths Non WHO African Region WHO Member States with no ongoing events W E S Graded events † 2 6 5 Grade 3 events Grade 2 events Grade 1 events 32 22 20 41 Ungraded events ProtractedProtracted 3 3 events events Protracted 2 events ProtractedProtracted 1 1 events event 1 Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Overview Contents This Weekly Bulletin focuses on selected acute public health emergencies occurring in the WHO African Region. -

DRC Humanitarian Situation Report

DRC Humanitarian Situation Report July, 2018 SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights 4.49 million Internally Displaced - On 24 July 2018, the Ministry of Health officially declared the end of Persons (IDPs) (OCHA, April 2018) the Ebola epidemic outbreak in the province of Equator. UNICEF’s response on the Ebola outbreak can be found on Ebola’s latest 7,900,000 children in need of situation report and situation reports since the beginning of the humanitarian assistance (OCHA, Jan.2018) outbreak. - On 01 August 2018, the Ministry of Public Health in the DRC 2,000,000 children are suffering from declared an Ebola outbreak in the province of North Kivu. No Sever Acute malnutrition (DRC Cluster epidemiological link has been identified between the Equator and Nutrition, May 2018) North Kivu outbreak. UNICEF’s response on the North Kivu Ebola outbreak can be found on weekly basis on Ebola’s latest situation 15,158 cases of cholera reported since report January 2018 (Ministry of Health, July 2018) - During the month of July, 122,241 persons were provided with essential household items and shelter materials, through the Rapid Response to Population Movement (RRMP) mechanism UNICEF Appeal 2018 US$ 268 million UNICEF’s Response with Partners 32% of required funds available Funding status 2018* UNICEF Sector/Cluster UNICEF Total Cluster Total Target Results* Target Results* Funds Nutrition : # of children with SAM received 1,140,000 88,521 1,306,000 129,351 admitted for therapeutic care 21% $56M Health : # of children in humanitarian situations 979,784 652,396 -

Democratic Republic of Congo Constitution

THE CONSTITUTION OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO, 2005 [1] Table of Contents PREAMBLE TITLE I GENERAL PROVISIONS Chapter 1 The State and Sovereignty Chapter 2 Nationality TITLE II HUMAN RIGHTS, FUNDAMENTAL LIBERTIES AND THE DUTIES OF THE CITIZEN AND THE STATE Chapter 1 Civil and Political Rights Chapter 2 Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Chapter 3 Collective Rights Chapter 4 The Duties of the Citizen TITLE III THE ORGANIZATION AND THE EXERCISE OF POWER Chapter 1 The Institutions of the Republic TITLE IV THE PROVINCES Chapter 1 The Provincial Institutions Chapter 2 The Distribution of Competences Between the Central Authority and the Provinces Chapter 3 Customary Authority TITLE V THE ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COUNCIL TITLE VI DEMOCRACY-SUPPORTING INSTITUTIONS Chapter 1 The Independent National Electoral Commission Chapter 2 The High Council for Audiovisual Media and Communication TITLE VII INTERNATIONAL TREATIES AND AGREEMENTS TITLE VIII THE REVISION OF THE CONSTITUTION TITLE IX TRANSITORY AND FINAL PROVISIONS PREAMBLE We, the Congolese People, United by destiny and history around the noble ideas of liberty, fraternity, solidarity, justice, peace and work; Driven by our common will to build in the heart of Africa a State under the rule of law and a powerful and prosperous Nation based on a real political, economic, social and cultural democracy; Considering that injustice and its corollaries, impunity, nepotism, regionalism, tribalism, clan rule and patronage are, due to their manifold vices, at the origin of the general decline -

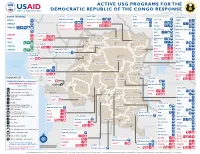

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS for the DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC of the CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS FOR THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20 BAS-UELE HAUT-UELE ITURI S O U T H S U D A N COUNTRYWIDE NORTH KIVU OCHA IMA World Health Samaritan’s Purse AIRD Internews CARE C.A.R. Samaritan’s Purse Samaritan’s Purse IMA World Health IOM UNHAS CAMEROON DCA ACTED WFP INSO Medair FHI 360 UNICEF Samaritan’s Purse Mercy Corps IMA World Health NRC NORD-UBANGI IMC UNICEF Gbadolite Oxfam ACTED INSO NORD-UBANGI Samaritan’s WFP WFP Gemena BAS-UELE Internews HAUT-UELE Purse ICRC Buta SCF IOM SUD-UBANGI SUD-UBANGI UNHAS MONGALA Isiro Tearfund IRC WFP Lisala ACF Medair UNHCR MONGALA ITURI U Bunia Mercy Corps Mercy Corps IMA World Health G A EQUATEUR Samaritan’s NRC EQUATEUR Kisangani N Purse WFP D WFPaa Oxfam Boende A REPUBLIC OF Mbandaka TSHOPO Samaritan’s ATLANTIC NORTH GABON THE CONGO TSHUAPA Purse TSHOPO KIVU Lake OCEAN Tearfund IMA World Health Goma Victoria Inongo WHH Samaritan’s Purse RWANDA Mercy Corps BURUNDI Samaritan’s Purse MAI-NDOMBE Kindu Bukavu Samaritan’s Purse PROGRAM KEY KINSHASA SOUTH MANIEMA SANKURU MANIEMA KIVU WFP USAID/BHA Non-Food Assistance* WFP ACTED USAID/BHA Food Assistance** SA ! A IMA World Health TA N Z A N I A Kinshasa SH State/PRM KIN KASAÏ Lusambo KWILU Oxfam Kenge TANGANYIKA Agriculture and Food Security KONGO CENTRAL Kananga ACTED CRS Cash Transfers For Food Matadi LOMAMI Kalemie KASAÏ- Kabinda WFP Concern Economic Recovery and Market Tshikapa ORIENTAL Systems KWANGO Mbuji T IMA World Health KWANGO Mayi TANGANYIKA a KASAÏ- n Food Vouchers g WFP a n IMC CENTRAL y i k -

UNJHRO) MONUSCO – OHCHR March 2021 REPORTED HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS in DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC of the CONGO (DRC)

Protection of civilians: Human rights violations documented in provinces affected by conflict United Nations Joint Human Rights Office in the DRC (UNJHRO) MONUSCO – OHCHR March 2021 REPORTED HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO (DRC) Figure 1. Percentage of violations per territory Figure 2. Number of violations per province in DRC SOUTH CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC SUDAN North Kivu Tanganyika Bas-Uele Haut-Uele Masisi 79% 21 Kalemie 36% 65 North-Ubangi Beni 64 36 Manono0 100 2 UGANDA CAMEROON South-Ubangi Rutshuru 69 31 Moba0 100 Ituri Mongala Lubero 29 71 77 Nyiragongo 86 14 Maniema Tshopo Walikale 90 10 Kabambare 63% 395 CONGO Equateur North Butembo0 100 Kasongo0 100 Kivu Kibombo0 100 GABON Tshuapa 359 South Kivu RWANDA Kasai Shabunda 82% 18 Mai-Ndombe Kamonia (Kas.)0 100% Kinshasa Uvira 33 67 5 BURUNDI Llebo (Kas.)0 100 Sankuru 15 63 Fizi 33 67 Kasai South Tshikapa (Kas.)0 100 Maniema Kivu Kabare 100 0 Luebo (Kas.)0 100 Kwilu 23 TANZANIA Walungu 29 71 Kananga (Kas. C)0 100 Lomami Bukavu0 100 22 4 Demba (Kas. C)0 100 Kongo 46 Mwenga 67 33 Central Luiza (Kas. C)0 100 Kwango Tanganyika Kalehe0 100 Kasai Dimbelenge (Kas. C)0 100 Central Haut-Lomami Ituri Miabi (Kas. O)0 100 Kasai 0 100 ANGOLA Oriental Irumu 88% 12 Mbuji-Mayi (Kas. O) Haut- Djugu 64 36 Lualaba Bas-Uele Katanga Mambasa 30 70 Buta0 100% Mahagi 100 0 % by armed groups % by State agents The boundaries and names shown and designations ZAMBIA used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

Democratic Republic of Congo

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO 350 Fifth Ave 34 th Floor New York, N.Y. 10118-3299 http://www.hrw.org (212) 290-4700 Vol. 15, No. 11 (A) - July 2003 I hid in the mountains and went back down to Songolo at about 3:00 p.m. I saw many people killed and even saw traces of blood where people had been dragged. I counted 82 bodies most of whom had been killed by bullets. We did a survey and found that 787 people were missing – we presumed they were all dead though we don’t know. Some of the bodies were in the road, others in the forest. Three people were even killed by mines. Those who attacked knew the town and posted themselves on the footpaths to kill people as they were fleeing. -- Testimony to Human Rights Watch ITURI: “COVERED IN BLOOD” Ethnically Targeted Violence In Northeastern DR Congo 1630 Connecticut Ave, N.W., Suite 500 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road 15 Rue Van Campenhout Washington, DC 20009 London N1 9HF, UK 1000 Brussels, Belgium TEL (202) 612-4321 TEL: (44 20) 7713 1995 TEL (32 2) 732-2009 FAX (202) 612-4333 FAX: (44 20) 7713 1800 FAX (32 2) 732-0471 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] “You cannot escape from the horror” This story of fifteen-year-old Elise is one of many in Ituri. She fled one attack after another and witnessed appalling atrocities. Walking for more than 300 miles in her search for safety, Elise survived to tell her tale; many others have not. -

Democratic Republic of Congo Democratic Republic of Congo Gis Unit, Monuc Africa

Map No.SP. 103 ADMINISTRATIVE MAP OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO GIS UNIT, MONUC AFRICA 12°30'0"E 15°0'0"E 17°30'0"E 20°0'0"E 22°30'0"E 25°0'0"E 27°30'0"E 30°0'0"E Central African Republic N N " " 0 0 ' Sudan ' 0 0 ° ° 5 5 Z o n g oBangui Mobayi Bosobolo Gbadolite Yakoma Ango Yaounde Bondo Nord Ubangi Niangara Faradje Cameroon Libenge Bas Uele Dungu Bambesa Businga G e m e n a Haut Uele Poko Rungu Watsa Sud Ubangi Aru Aketi B u tt a II s ii rr o r e Kungu Budjala v N i N " R " 0 0 ' i ' g 0 n 0 3 a 3 ° b Mahagi ° 2 U L ii s a ll a Bumba Wamba 2 Orientale Mongala Co Djugu ng o R i Makanza v Banalia B u n ii a Lake Albert Bongandanga er Irumu Bomongo MambasaIturi B a s a n k u s u Basoko Yahuma Bafwasende Equateur Isangi Djolu Yangambi K i s a n g a n i Bolomba Befale Tshopa K i s a n g a n i Beni Uganda M b a n d a k a N N " Equateur " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° Lubero ° 0 Ingende B o e n d e 0 Gabon Ubundu Lake Edward Opala Bikoro Bokungu Lubutu North Kivu Congo Tshuapa Lukolela Ikela Rutshuru Kiri Punia Walikale Masisi Monkoto G o m a Yumbi II n o n g o Kigali Bolobo Lake Kivu Rwanda Lomela Kalehe S S " KabareB u k a v u " 0 0 ' ' 0 Kailo Walungu 0 3 3 ° Shabunda ° 2 2 Mai Ndombe K ii n d u Mushie Mwenga Kwamouth Maniema Pangi B a n d u n d u Bujumbura Oshwe Katako-Kombe South Kivu Uvira Dekese Kole Sankuru Burundi Kas ai R Bagata iver Kibombo Brazzaville Ilebo Fizi Kinshasa Kasongo KasanguluKinshasa Bandundu Bulungu Kasai Oriental Kabambare K e n g e Mweka Lubefu S Luozi L u s a m b o S " Tshela Madimba Kwilu Kasai -

Case 1:19-Cv-03737 Document 1 Filed 12/15/19 Page 1 of 79

Case 1:19-cv-03737 Document 1 Filed 12/15/19 Page 1 of 79 TERRENCE COLLINGSWORTH (DC Bar # 471830) International Rights Advocates 621 Maryland Ave NE Washington, D.C. 20002 Tel: 202-543-5811 E-mail: [email protected] Counsel for Plaintiffs UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ________________ JANE DOE 1, Individually and on behalf of Proposed Class Members; JOHN DOE 1, Individually and on behalf of Proposed Class Members; JOHN DOE 2, Individually and on behalf of Proposed Class Members; JENNA ROE 3, Individually and on behalf of Proposed Class Members; JAMES DOE 4, Individually and on Case No. CV: behalf of Proposed Class Members; JOHN DOE 5, Individually and on behalf of Proposed Class Members; JENNA DOE 6, Individually and on CLASS COMPLAINT FOR behalf of Proposed Class Members; INJUNCTIVE RELIEF AND JANE DOE 2, Individually and on DAMAGES behalf of Proposed Class Members; JENNA DOE 7, Individually and on behalf of Proposed Class Members; JURY TRIAL DEMANDED JENNA DOE 8, Individually and on behalf of Proposed Class Members; JOHN DOE 9, Individually and on behalf of Proposed Class Members; JENNA DOE 10, Individually and on behalf of Proposed Class Members; JENNA DOE 11, Individually and on behalf of Proposed Class Members; JANE DOE 3, Individually and on behalf of Proposed Class Members; JOHN DOE 12, Individually and on 1 Case 1:19-cv-03737 Document 1 Filed 12/15/19 Page 2 of 79 behalf of Proposed Class Members; and JOHN DOE 13, Individually and on behalf of Proposed Class Members; all Plaintiffs C/O 621 Maryland Ave. -

The Current Situation in the Democratic Republic of Congo

Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg., 103(6), 2020, pp. 2168–2170 doi:10.4269/ajtmh.20-1169 Copyright © 2020 by The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene Perspective Piece COVID-19: The Current Situation in the Democratic Republic of Congo Carl Agisha Juma,1† Nestor Kalume Mushabaa,2† Feruzi Abdu Salam,1,3† Attaullah Ahmadi,4*† and Don Eliseo Lucero-Prisno III5,6† 1Global Health Focus Africa, Bukavu, The Democratic Republic of Congo; 2Department of Gaenecology, University of Goma, Goma, The Democratic Republic of Congo; 3Health Maintenance Organization in Africa, Goma, The Democratic Republic of Congo; 4Kabul University of Medical Sciences, Kabul, Afghanistan; 5Department of Global Health and Development, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, United Kingdom; 6Faculty of Management and Development Studies, University of the Philippines (Open University), Los Baños, Philippines Abstract. COVID-19 is a highly contagious disease that has affected all African countries including the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Formidable challenges limit precautionary measures which were instituted by the government to curb the pandemic. Insufficient COVID-19 testing laboratories, limited medical and personal protective equipment, and an inadequate number of health workers leave the country ill-equipped in the fight against the pandemic. Lack of assistance from the government to those who lost their jobs due to lockdown forced these individuals to go outside to find provisions, thus increasing the spread of the virus. Moreover, the fragile healthcare system is overburdened by civil conflicts and other epidemics and endemics amid the COVID-19 pandemic. The conflicts have led to thousands of deaths and hundreds of thousands of displacements and deprived many people of basic health services. -

Country Fact Sheet, Democratic Republic of the Congo

Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets file:///C:/Documents and Settings/brendelt/Desktop/temp rir/Country Fact... Français Home Contact Us Help Search canada.gc.ca Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets Home Country Fact Sheet DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO April 2007 Disclaimer This document was prepared by the Research Directorate of the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada on the basis of publicly available information, analysis and comment. All sources are cited. This document is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed or conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. For further information on current developments, please contact the Research Directorate. Table of Contents 1. GENERAL INFORMATION 2. POLITICAL BACKGROUND 3. POLITICAL PARTIES 4. ARMED GROUPS AND OTHER NON-STATE ACTORS 5. FUTURE CONSIDERATIONS ENDNOTES REFERENCES 1. GENERAL INFORMATION Official name Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) Geography The Democratic Republic of the Congo is located in Central Africa. It borders the Central African Republic and Sudan to the north; Rwanda, Burundi, Uganda and Tanzania to the east; Zambia and Angola to the south; and the Republic of the Congo to the northwest. The country has access to the 1 of 26 9/16/2013 4:16 PM Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets file:///C:/Documents and Settings/brendelt/Desktop/temp rir/Country Fact... Atlantic Ocean through the mouth of the Congo River in the west. The total area of the DRC is 2,345,410 km². -

Review of the National Program for Onchocerciasis Control in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease Review Review of the National Program for Onchocerciasis Control in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Jean-Claude Makenga Bof 1,* , Fortunat Ntumba Tshitoka 2, Daniel Muteba 2, Paul Mansiangi 3 and Yves Coppieters 1 1 Ecole de Santé Publique, Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB), Route de Lennik 808, 1070 Brussels, Belgium; [email protected] 2 Ministry of Health: Program of Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTD) for Preventive Chemotherapy (PC), Gombe, Kinshasa, DRC; [email protected] (F.N.T.); [email protected] (D.M.) 3 Faculty of Medicine, School of Public Health, University of Kinshasa (UNIKIN), Lemba, Kinshasa, DRC; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +32-493-93-96-35 Received: 3 May 2019; Accepted: 30 May 2019; Published: 13 June 2019 Abstract: Here, we review all data available at the Ministry of Public Health in order to describe the history of the National Program for Onchocerciasis Control (NPOC) in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Discovered in 1903, the disease is endemic in all provinces. Ivermectin was introduced in 1987 as clinical treatment, then as mass treatment in 1989. Created in 1996, the NPOC is based on community-directed treatment with ivermectin (CDTI). In 1999, rapid epidemiological mapping for onchocerciasis surveys were launched to determine the mass treatment areas called “CDTI Projects”. CDTI started in 2001 and certain projects were stopped in 2005 following the occurrence of serious adverse events. Surveys coupled with rapid assessment procedures for loiasis and onchocerciasis rapid epidemiological assessment were launched to identify the areas of treatment for onchocerciasis and loiasis. -

UNJHRO) MONUSCO – OHCHR July 2020 REPORTED HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS in DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC of the CONGO (DRC)

Protection of civilians: Human rights violations documented in provinces affected by conflict United Nations Joint Human Rights Office in the DRC (UNJHRO) MONUSCO – OHCHR July 2020 REPORTED HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO (DRC) Figure 1. Percentage of violations per territory Figure 2. Number of violations per province in DRC SOUTH North Kivu Kasai CAR SUDAN Masisi 93% 7% Demba (Kas. C) 100% Nyiragongo 84% 16% Dibaya (Kas. C) 100% Bas-Uele Haut-Uele North-Ubangi Beni 79% 21% Kananga (Kas.C) 100% UGANDA CAMEROON South-Ubangi Rutshuru 88% 12% Kazumba (Kas. C) 100% Mongala Lubero 40% 60% Dimbelenge (Kas.C) 100% 95 Tshikapa (Kas.) 100% Ituri Walikale 76% 24% Tshopo CONGO Equateur Goma 100% Kamonia (Kas.) 100% North Kivu Butembo 100% Ilebo (Kas.) 100% GABON Tshuapa 383 Luebo (Kas.) 100% South Kivu RWANDA Mweka (Kas.) 100% Mwenga 60% 40% Mai-Ndombe Uvira 33% 67% Tshilenge (Kas. O) 100% Kinshasa BURUNDI Kasai Sankuru 25 51 Kalehe 71% 29% Mbuji-Mayi (Kas. O) 100% South Bukavu 100% Miabi (Kas. O) 100% Maniema Kivu TANZANIA Fizi 40% 60% Maniema Kwilu 27 Lomami 100% Kabambare 39 Shabunda 44% 56% Kongo 15 59 Walungu 100% Kindu 100% Central Kwango Tanganyika 100%Ituri Kasongo Kasai 100% Central Walungu 100% Haut-Lomami Djugu 38% 62% 100% Tanganyika Kasai Irumu 100% Kalemie 16% 100% 84% ANGOLA Oriental Mahagi 100% 100% Nyunzu 70% 100% 30% Lualaba Haut- Aru Katanga 100% Moba 100%100% Mambasa 100% Manono 100% Bunia 100% Kabalo 100% The boundaries and names shown and designations ZAMBIA % by State agents used on this map do not imply official endorsement % by armed groups or acceptance by the United Nations.