Finding Your Chinese Roots

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charting a New Course for Chinese Diaspora Archaeology in North America

1 Charting a New Course for Chinese Diaspora Archaeology in North America J. Ryan Kennedy and Chelsea Rose The archaeology of the Chinese diaspora in North America has reached a critical moment in its development. On one hand, archaeologists investigat- ing Chinese diaspora communities have produced an incredibly rich body of data relating to the material lives of Chinese people who migrated to the United States and Canada in the nineteenth century. Although much of this work has focused on urban Chinatowns (e.g., Allen et al. 2002; Great Basin Foundation 1987; Praetzellis and Praetzellis 1982, 1997; Voss 2008), an ever- increasing number of projects examine Chinese lives in diverse contexts in- cluding rural towns (Rose Chapter 7 this volume; Warner et al. 2014), mining camps (LaLande 1982; Longenecker and Stapp 1993), railroad-related sites (Kennedy et al. 2019; Voss 2015a), lumber camps (Sunseri 2015a, 2015b, Chap- ter 11 this volume), and fishing and shrimping sites (Bentz and Braje, Chapter 12 this volume; Schulz 1996; Williams 2011). On the other hand, the stories told by archaeologists of the Chinese diaspora have generally failed to speak to archaeological theory more broadly. As we discuss below, this derives from two primary causes: (1) the continued use of theoretical and methodological approaches that foreground binary notions of continuity and change, and (2) a tendency to tell the stories of Chinese diaspora communities from a North American perspective that ignores the many transnational facets of Chinese migrant lives. If Chinese diaspora archaeology is to avoid theoretical stagna- tion and contribute to larger academic and popular debates about topics in- cluding immigration, diaspora, and globalization, then its practitioners must chart a new direction. -

Languages Supported Spring 2020

LANGUAGES SUPPORTED SPRING 2020 1-888-556-5541 Languages in Motion Ltd. #300, 404 6th Ave SW Calgary, AB, T2P 0R9 On-Site Interpreters | Scheduled LD1 LD2 Arabic Kinyarwanda* Cambodian (Khmer)* Albanian* Kiswahili* Japanese Amharic Korean Armenian Kurdish - Bahdini* Assyrian Kurdish - Kurde* Azerbaijani* Kurdish - Kurmanchi* Bengali* Kurdish - Sorani* Bulgarian* Lingala* Chao-Chow* Macedonian* Chin (Hakachin)* Malayalam* Chinese (Cantonese)* Nepali* Chinese (Mandarin) Oromo Chinese (Hakka)* Pashto Chinese (Hokkien)* Persian/Farsi Chinese (Shanghainese)* Polish Chinese (Taishanese)* Portuguese Chinese (Toisanese)* Punjabi Dari Romanian* Dinka* Russian French Somali* Fukinese* Spanish German Swahili* Greek* Tagalog/Filipino* Gujarati* Tamil* Hebrew* Tigrinya* Hindi Turkish Igbo* Twi* Ilocano* Ukrainian Italian* Urdu Kikuyu* Vietnamese* Kinyamulenge* *Availability varies as there are only one or two local interpreters available. Your Account Manager will contact you if an interpreter is not available for the selected time and arrange a different date or suggest OPI/VRI service. On-Demand & Scheduled Video Remote Interpreters Fully Supported for VRI From 8am MST-10pm MST Pilot phase for the select VRI languages From Monday to Friday Hold and connections times may vary LD1 LD2 LD2 Arabic Burmese Amharic Chinese (Cantonese) Nepali Guianese Creole Chinese (Mandarin) Somali Gujarati French Swahili Haitian Creole Hindi Korean Vietnamese Hmong Portuguese (Brazil) Hungarian Portuguese (Portugal) Italian Russian Japanese Spanish Kabuverdianu Karen -

2019年第3季度在韩国注册的中国水产企业名单the List of Chinese

2019年第3季度在韩国注册的中国水产企业名单 The List of Chinese Registered Fishery Processing Establishments Export to Korea (Total 1347 , the third quarter of 2019,updated on 25 June, 2019) No. Est.No. 企业名称(中文) Est.Name 企业地址(中文) Est.Address 产品(Products) 北京市朝阳区崔各庄乡 The 23rd floor Sanyuan Property Jingmi Road 北京中洋环球金枪鱼有 1 1100/02010 Beijing Zhongyang Global Tuna Co.,Ltd 东辛店村京密路三元物 Dongxindian Village Cuigezhuang TownChaoyang Fishery Products 限公司 业院内23号楼 District Beijng 五洋海产(天津)有限 天津市塘沽区东江路 2 1200/02004 Ocean Products (Tian.Jin) Co., Ltd Dongjiang Road No.3849 Tanggu Tianjin Fishery Products 公司 3849号 欧盛实业(天津)有限 天津经济技术开发区渤 No.5, Bohai Road, Tianjin Economic & Technological 3 1200/02019 Ocean (Tianjin) Corporation Ltd. Fishery Products 公司 海路5号 Development Area, Tianjin 天津市颖明海湾食品有 天津市滨海新区中心渔 No.221 Yuehai RD., Binhai New Area Of The City 4 1200/02028 Tianjin Smart Gulf Foodstuffs Co.,Ltd. Fishery Products 限公司 港经济区悦海路221号 Center Fishing Port Economic Zone, Tianjin, China 天津市塘沽区海华水产 Tianjin Tanggu District Haihua Fishery Products Food 天津市塘沽区北塘镇水 No. 9, Shuichan Road, Beitang Town, Tanggu District, 5 1200/02048 Fishery Products 食品有限公司 Co., Ltd. 产路9号 Tianjin 天津百迅达进出口贸易 天津市津南区双桥河镇 South Dongnigu Village, Shuangqiaohe Town, Jinnan 6 1200/02063 Tianjin baixunda import and export trade Co., Ltd Fishery Products 有限公司 东泥沽村南 District, Tianjin, China 昌黎县筑鑫实业有限公 秦皇岛市昌黎县新开口 Economic Development Zone Xinkaikou Changli 7 1300/02228 Changli Zhuxin Enterprises Co., Ltd. Fishery Products 司 经济开发区 County Qinhuangdao 抚宁县渤远水产品有限 秦皇岛市抚宁县台营镇 Yegezhuang village taiying town funing county 8 1300/02229 Funing county boyuan aquatic products co.,ltd Fishery Products 公司 埜各庄村 Qinhuangdao city Hebei province 秦皇岛市江鑫水产冷冻 河北省秦皇岛北戴河新 Nandaihe Second District,Beidaihe New 9 1300/02236 Qinhuangdao Jiangxin Aquatic Food Products Co., Ltd. -

List of Languages-OPI

OVER-THE-PHONE INTERPRETING SERVICES IN 200+LANGUAGES ON DEMAND Acholi Finnish Kizigua (Kizigula) Q’anjob’al Afghani Flemish Korean Rohingya Afrikaans French Kosraean Romanian Akan French Canadian Krahn Russian Akateko French Creole Krio Samoan Albanian Fulde Kunama Senthang Amharic Fulfulde (Fulani) Kurdish Serbian Anuak Fuzhou (Foochow, Fuchow) Kurdish (Bahdini) Shanghainese Arabic Ga Kurdish (Kurmanji) Shona Armenian Garre Kurdish (Sorani) Sichuanese Ashanti Georgian Kyrgyz Sicilian Assyrian German Lao Sinhala (Sinhalese) Azeri Greek Latvian Siyin Bahasa (Malaysian) Guarani Lingala Slovak Bambara Gujarati Lithuanian Slovene Bashkir Hainanese Lorma Somali Basque Haitian Creole Luganda Somali Bantu Bassa Hakka (Chinese) Luo Soninke Belarusian Harari Maay-Maay Soninke (Sarahuli) Bengali Hassaniya Macedonian Soninke (Sarakhole) Bosnian Hausa Malay Soranî (Kurdish) Bulgarian Hebrew Malayalam Spanish Burmese Hiligaynon (Ilonggo) Mam Susu (Sousou) Carolinian Hindi Mandinka Swahili Catalan Hmong Mara Swedish Cebuano Hokkien (Fujianese, Fukienese) Marathi Sylheti Chaldean Neo-Aramaic Hungarian Marshallese Tagalog (Filipino) Chamorro Icelandic Matu Taishanese (Toishanese) Chin Igbo Mbay Taiwanese Chin (Falam) Ilocano Mende Tajik Chin (Hakha) Indonesian Mina Tamil Chin (Lai) Italian Mixteco (Alto) Telugu Chin (Lautu) Iu Mien Mixteco (Bajo) Teochew (Chaochow) Chin (Mizo) Japanese Mongolian Thai Chin (Tedim) Jarai Montenegrin Tibetan Chin (Zo, Zomi) Jiangsu Mòoré (More, Mossi) Tigrinya Chin (Zophei) Jula (Dioula) Mushunguli Tongan Chinese Cantonese -

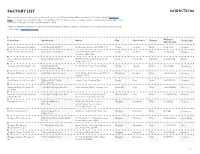

Factory List

FACTORY LIST Our commitment to transparency is core to our Corporate Social Responsibility efforts. Nordstrom’s Tier 1 factory list for Nordstrom Made, our family of private-label brands, is included below. This list reflects our most strategic suppliers, which we classify internally as Level 1 and Level 2. The data is current as of December 11, 2020. Additional information about our commitment to human rights, including our goals for ethical labor practices and women’s empowerment, can be found on nordstromcares.com. Factory Name Manufacturer Address City State/Province Country Employees Product Type (Male/Female) Industria de Calcados Karlitos Ltda. South Service Trading S/A Rua Benedito Merlino, 999, 14405-448 Franca Sao Paulo Brazil 146 (62/84) Footwear Industria de Calcados Kissol Ltda. South Service Trading S/A Rua Irmãos Antunes, 813, Jardim Franca Sao Paulo Brazil 196 (137/59) Footwear Guanabara, 14405-445 Eminent Garment (Cambodia) Eminent Garment Limited Phum Preak Thmey, Khum Teukvil, Srok Saang Khet Kandal Cambodia 866 (105/761) Woven Limited Saang, Phnom Penh Zhejiang Sunmans Knitting Co. Ltd. Royal Bermuda LLC No. 139 North of Biyun Road, 314400 Haining Zhejiang China 197 (39/158) Accessories West Coast Hosiery Group Dongguan Mayflower Footwear Corp. Pagoda International Footwear Golden Dragon Road, 1st Industrial Park of Dongcheng Dongguan China 500 (350/150) Footwear Sangyuan, 523119 Fujian Fuqing Huatai Footwear Co. Madden Intl. Ltd. Trading Lingjiao Village, Shangjing Town Fuqing Fujian China 360 (170/190) Footwear Ltd. Dolce Vita Intl. Nanyuan Knitting & Garments Co. South Asia Knitting Factory Ltd. Nanhua Industry District, Shengxin Town Nanan City Fujian China 604 (152/452) Sweaters Ltd. -

Official Gazette Vol. 49.Pdf

ສາທາລະນະລດັ ປະຊາທິປະໄຕ ປະຊາຊນົ ລາວ LAO PEOPLE’S DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC ກະຊວງ ວທິ ະຍາສາດ ແລະ ເຕັກໂນໂລຊ ີ ກມົ ຊບັ ສນິ ທາງປນັ ຍາ MINISTRY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY DEPARTMENT OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY ຈດົ ໝາຍເຫດທາງລດັ ຖະການ ກຽ່ ວກບັ ການເຜີຍແຜຜ່ ນົ ຂອງການຈດົ ທະບຽນ ຊບັ ສນິ ອດຸ ສາຫະກາ ຢ່ ສປປ ລາວ OFFICIAL GAZETTE OF INDUSTRIAL PROPERTY ສະບບັ ທີ (Vol.) 49 Official Gazette of Industrial Property Vol. 49, 09/2012 ສາລະບານ ພາກທີ່ I: ຜນົ ຂອງການຈດົ ທະບຽນເຄີ່ ອ ງໝາຍການຄາ້ ພາກທ II: ຜນົ ຂອງການຕີ່ ອາຍກຸ ານຈດົ ທະບຽນເຄີ່ ອ ງໝາຍການຄາ້ CONTENT Part I: Registration of Trademark Part II: Renewal of Trademark I Official Gazette of Industrial Property Vol. 49, 09/2012 ພາກທ I ຜນົ ຂອງການຈດົ ທະບຽນເຄີ່ ອ ງໝາຍການຄາ້ ຄາ ແນະນາ ກຽີ່ ວກບັ ລະຫດັ ຫຍ ້ (540) ເຄີ່ ອງໝາຍການຄາ້ (511) ໝວດຂອງສນິ ຄາ້ ແລະ ການບ ລິການ (210) ເລກທ ຄາ ຮອ້ ງ (220) ວນັ ທ ທີ່ ຍີ່ ນຄາ ຮອ້ ງ (731) ຊີ່ ແລະ ທີ່ ຢີ່ ຂອງຜຍ້ ີ່ ນ ຄາ ຮອ້ ງ (111) ເລກທ ໃບທະບຽນເຄີ່ ອງໝາຍການຄາ້ (180) ວນັ ໝດົ ອາຍຂຸ ອງໃບທະບຽນ Part I Registration of Trademark Introduction of Codes (540) Trademark (511) Classification of goods and services (Nice Classification) (210) Number of the application (220) Date of filing of the application (730) Name and Address of applicant (111) Number of the registration (180) Expiration date of the registration/renewal II Official Gazette of Industrial Property Vol. 49, 09/2012 ( 540 ) (511) 01 (210) No. 25716 (220) 01/02/2012 (732) Poodang 168 (Thailand) Co., Ltd. 34/6 Moo 1, Chaengwattana Road, Tambol Klongklue, Amphur Pakkat, Nonthaburi Province, Thailand (111) No. 25051 (180) 01/02/2022 ( 540 ) (511) 01 (210) No. 25717 (220) 01/02/2012 (732) Poodang 168 (Thailand) Co., Ltd. -

The Changing Chinese Linguistic Situation in Suriname Under New Migration

CHAPTER 9 They Might as Well Be Speaking Chinese: The Changing Chinese Linguistic Situation in Suriname under New Migration Paul B. Tjon Sie Fat 1 Introduction This chapter presents one of the most obvious local examples, to the Surinamese public at least, of the link between mobility, language, and iden- tity: current Chinese migration. These ‘New Chinese’ migrants since the 1990s were linguistically quite different from the established Hakkas in Suriname, and were the cause of an upsurge in anti-Chinese sentiments. It will be argued that the aforementioned link is constructed in the Surinamese imagination in the context of ethnic and civic discourse to reproduce the image of a mono- lithic, undifferentiated, Chinese migrant group, despite increasing variety and change within the Chinese segment of Surinamese society. The point will also be made that the Chinese stereotype affects the way demographic and linguis- tic data relating to Chinese are produced by government institutions. We will present a historic overview of the Chinese presence in Suriname, a brief eth- nographic description of Chinese migrant cohorts, followed by some data on written Chinese in Suriname. Finally we present the available data on Chinese ethnicity and language from the Surinamese General Bureau of Statistics (abs). An ethnic Chinese segment has existed in Surinamese society since the middle of the nineteenth century, as a consequence of Dutch colonial policy to import Asian indentured labour as a substitute for African slave labour. Indentured labourers from Hakka villages in the Fuitungon Region (particu- larly Dongguan and Baoan)1 in the second half of the nineteenth century made way for entrepreneurial chain migrants up to the first half of the twentieth 1 The established Hakka migrants in Suriname refer to the area as fui5tung1on1 (惠東安), which is an anagram of the Kejia pronunciation of the names of the three counties where the ‘Old Chinese’ migrant cohorts in Suriname come from: fui5jong2 (惠陽 Putonghua: huìyáng), tung1kon1 (東莞 pth: dōngguǎn), and pau3on1 (寳安 pth: bǎoān). -

An Optimality Theoretic Analysis of Rising Changed Tones in Taishanese

An Optimality Theoretic Analysis of Rising Changed Tones in Taishanese Kevin Liang, University of Pennsylvania Taishanese is a member of the Siyi sub-branch of the Yue branch of the Sinitic languages. As described by Taishan Fangyin Zidian (2006), Taishanese has five phonemic tones: three level tones (55, 33, 22) and two falling tones (32, 21). Cheng (1973) describes a so-called “changed tone” process where the tonal contour of the underlying tones can be modified. Depending on the morphological or syntactic context, one of two processes can occur: a level or falling tone becomes a rising tone; or a level tone becomes a falling tone. The present work focuses on the former type of changed tone where a rising tone, which is otherwise not present in Taishanese, can be realized. In the present study, Taishanese tone letter 5 will be represented as H (a tone with the features [+high tone][-low tone][+modify]), tone letter 3 as M (a tone with the features [-high tone][-low tone][-modify]), and tone letter 2 as L (a tone with the features [-high tone][+low tone][+modify]). This is based on the system proposed by Wang (1967) and Woo (1969). Early work on rising changed tones in Taishanese, such as in Cheng (1973), claimed that the process was not phonologically motivated but mostly syntactically and morphologically motivated. Moreover, according to Cheng (1973), only a limited number of words, which are mostly nouns, can undergo this process. However, Him (1980) suggests that the rising changed tone in Taishanese may be the result of an operative process where rises can occur systematically, based on an analysis of related languages. -

THE MEDIA's INFLUENCE on SUCCESS and FAILURE of DIALECTS: the CASE of CANTONESE and SHAAN'xi DIALECTS Yuhan Mao a Thesis Su

THE MEDIA’S INFLUENCE ON SUCCESS AND FAILURE OF DIALECTS: THE CASE OF CANTONESE AND SHAAN’XI DIALECTS Yuhan Mao A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Language and Communication) School of Language and Communication National Institute of Development Administration 2013 ABSTRACT Title of Thesis The Media’s Influence on Success and Failure of Dialects: The Case of Cantonese and Shaan’xi Dialects Author Miss Yuhan Mao Degree Master of Arts in Language and Communication Year 2013 In this thesis the researcher addresses an important set of issues - how language maintenance (LM) between dominant and vernacular varieties of speech (also known as dialects) - are conditioned by increasingly globalized mass media industries. In particular, how the television and film industries (as an outgrowth of the mass media) related to social dialectology help maintain and promote one regional variety of speech over others is examined. These issues and data addressed in the current study have the potential to make a contribution to the current understanding of social dialectology literature - a sub-branch of sociolinguistics - particularly with respect to LM literature. The researcher adopts a multi-method approach (literature review, interviews and observations) to collect and analyze data. The researcher found support to confirm two positive correlations: the correlative relationship between the number of productions of dialectal television series (and films) and the distribution of the dialect in question, as well as the number of dialectal speakers and the maintenance of the dialect under investigation. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author would like to express sincere thanks to my advisors and all the people who gave me invaluable suggestions and help. -

China National Accord Medicines Corporation Ltd

China National Accord Medicines Corporation Ltd. Semi-Annual Report 2020 August 2020 1 Section I. Important Notice, Contents and Interpretation Board of Directors, Supervisory Committee, all directors, supervisors and senior executives of China National Accord Medicines Corporation Ltd. (hereinafter referred to as the Company) hereby confirm that there are no any fictitious statements, misleading statements, or important omissions carried in this report, and shall take all responsibilities, individual and/or joint, for the reality, accuracy and completion of the whole contents. Lin Zhaoxiong, Principal of the Company, Gu Guolin, person in charger of accounting works and Wang Ying, person in charge of accounting organ (accounting principal) hereby confirm that the Financial Report of Semi- Annual Report 2020 is authentic, accurate and complete. Other directors attending the Meeting for annual report deliberation except for the followed: Name of director absent Title for absent director Reasons for absent Attorney Lian Wanyong Director Official business Li Dongjiu The Company plans not to pay cash dividends, bonus and carry out capitalizing of common reserves. 2 Contents Semi-Annual Report 2020..................................................................................................................2 Section I Important Notice, Contents and Interpretation.............................................................. 2 Section II Company Profile and Main Financial Indexes...............................................................5 -

CHSA HP2010.Pdf

The Hawai‘i Chinese: Their Experience and Identity Over Two Centuries 2 0 1 0 CHINESE AMERICA History&Perspectives thej O u r n a l O f T HE C H I n E s E H I s T O r I C a l s OCIET y O f a m E r I C a Chinese America History and PersPectives the Journal of the chinese Historical society of america 2010 Special issUe The hawai‘i Chinese Chinese Historical society of america with UCLA asian american studies center Chinese America: History & Perspectives – The Journal of the Chinese Historical Society of America The Hawai‘i Chinese chinese Historical society of america museum & learning center 965 clay street san francisco, california 94108 chsa.org copyright © 2010 chinese Historical society of america. all rights reserved. copyright of individual articles remains with the author(s). design by side By side studios, san francisco. Permission is granted for reproducing up to fifty copies of any one article for educa- tional Use as defined by thed igital millennium copyright act. to order additional copies or inquire about large-order discounts, see order form at back or email [email protected]. articles appearing in this journal are indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: History and Life. about the cover image: Hawai‘i chinese student alliance. courtesy of douglas d. l. chong. Contents Preface v Franklin Ng introdUction 1 the Hawai‘i chinese: their experience and identity over two centuries David Y. H. Wu and Harry J. Lamley Hawai‘i’s nam long 13 their Background and identity as a Zhongshan subgroup Douglas D. -

Transnational Chinese Sphere in Singapore: Dynamics, Transformations and Characteristics, In: Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, 41, 2, 37-60

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs China aktuell Liu, Hong (2012), Transnational Chinese Sphere in Singapore: Dynamics, Transformations and Characteristics, in: Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, 41, 2, 37-60. ISSN: 1868-4874 (online), ISSN: 1868-1026 (print) The online version of this introduction and the other articles can be found at: <www.CurrentChineseAffairs.org> Published by GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies, Institute of Asian Studies in cooperation with the National Institute of Chinese Studies, White Rose East Asia Centre at the Universities of Leeds and Sheffield and Hamburg University Press. The Journal of Current Chinese Affairs is an Open Access publication. It may be read, copied and distributed free of charge according to the conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. To subscribe to the print edition: <[email protected]> For an e-mail alert please register at: <www.CurrentChineseAffairs.org> The Journal of Current Chinese Affairs is part of the GIGA Journal Family which includes: Africa Spectrum ●● Journal of Current Chinese Affairs Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs ●● Journal of Politics in Latin America <www.giga-journal-family.org> Journal of Current Chinese Affairs 2/2012: 37-60 Transnational Chinese Sphere in Singapore: Dynamics, Transformations and Characteristics LIU Hong Abstract: Based upon an empirical analysis of Singaporean Chinese’s intriguing and changing linkages with China over the past half century, this paper suggests that multi-layered interactions between the Chinese diaspora and the homeland have led to the formulation of an emerging transnational Chinese social sphere, which has three main characteristics: First, it is a space for communication by ethnic Chinese abroad with their hometown/ homeland through steady and extensive flows of people, ideas, goods and capital that transcend the nation-state borders, although states also play an important role in shaping the nature and characteris- tics of these flows.