Charting a New Course for Chinese Diaspora Archaeology in North America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019年第3季度在韩国注册的中国水产企业名单the List of Chinese

2019年第3季度在韩国注册的中国水产企业名单 The List of Chinese Registered Fishery Processing Establishments Export to Korea (Total 1347 , the third quarter of 2019,updated on 25 June, 2019) No. Est.No. 企业名称(中文) Est.Name 企业地址(中文) Est.Address 产品(Products) 北京市朝阳区崔各庄乡 The 23rd floor Sanyuan Property Jingmi Road 北京中洋环球金枪鱼有 1 1100/02010 Beijing Zhongyang Global Tuna Co.,Ltd 东辛店村京密路三元物 Dongxindian Village Cuigezhuang TownChaoyang Fishery Products 限公司 业院内23号楼 District Beijng 五洋海产(天津)有限 天津市塘沽区东江路 2 1200/02004 Ocean Products (Tian.Jin) Co., Ltd Dongjiang Road No.3849 Tanggu Tianjin Fishery Products 公司 3849号 欧盛实业(天津)有限 天津经济技术开发区渤 No.5, Bohai Road, Tianjin Economic & Technological 3 1200/02019 Ocean (Tianjin) Corporation Ltd. Fishery Products 公司 海路5号 Development Area, Tianjin 天津市颖明海湾食品有 天津市滨海新区中心渔 No.221 Yuehai RD., Binhai New Area Of The City 4 1200/02028 Tianjin Smart Gulf Foodstuffs Co.,Ltd. Fishery Products 限公司 港经济区悦海路221号 Center Fishing Port Economic Zone, Tianjin, China 天津市塘沽区海华水产 Tianjin Tanggu District Haihua Fishery Products Food 天津市塘沽区北塘镇水 No. 9, Shuichan Road, Beitang Town, Tanggu District, 5 1200/02048 Fishery Products 食品有限公司 Co., Ltd. 产路9号 Tianjin 天津百迅达进出口贸易 天津市津南区双桥河镇 South Dongnigu Village, Shuangqiaohe Town, Jinnan 6 1200/02063 Tianjin baixunda import and export trade Co., Ltd Fishery Products 有限公司 东泥沽村南 District, Tianjin, China 昌黎县筑鑫实业有限公 秦皇岛市昌黎县新开口 Economic Development Zone Xinkaikou Changli 7 1300/02228 Changli Zhuxin Enterprises Co., Ltd. Fishery Products 司 经济开发区 County Qinhuangdao 抚宁县渤远水产品有限 秦皇岛市抚宁县台营镇 Yegezhuang village taiying town funing county 8 1300/02229 Funing county boyuan aquatic products co.,ltd Fishery Products 公司 埜各庄村 Qinhuangdao city Hebei province 秦皇岛市江鑫水产冷冻 河北省秦皇岛北戴河新 Nandaihe Second District,Beidaihe New 9 1300/02236 Qinhuangdao Jiangxin Aquatic Food Products Co., Ltd. -

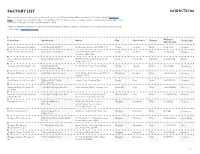

Factory List

FACTORY LIST Our commitment to transparency is core to our Corporate Social Responsibility efforts. Nordstrom’s Tier 1 factory list for Nordstrom Made, our family of private-label brands, is included below. This list reflects our most strategic suppliers, which we classify internally as Level 1 and Level 2. The data is current as of December 11, 2020. Additional information about our commitment to human rights, including our goals for ethical labor practices and women’s empowerment, can be found on nordstromcares.com. Factory Name Manufacturer Address City State/Province Country Employees Product Type (Male/Female) Industria de Calcados Karlitos Ltda. South Service Trading S/A Rua Benedito Merlino, 999, 14405-448 Franca Sao Paulo Brazil 146 (62/84) Footwear Industria de Calcados Kissol Ltda. South Service Trading S/A Rua Irmãos Antunes, 813, Jardim Franca Sao Paulo Brazil 196 (137/59) Footwear Guanabara, 14405-445 Eminent Garment (Cambodia) Eminent Garment Limited Phum Preak Thmey, Khum Teukvil, Srok Saang Khet Kandal Cambodia 866 (105/761) Woven Limited Saang, Phnom Penh Zhejiang Sunmans Knitting Co. Ltd. Royal Bermuda LLC No. 139 North of Biyun Road, 314400 Haining Zhejiang China 197 (39/158) Accessories West Coast Hosiery Group Dongguan Mayflower Footwear Corp. Pagoda International Footwear Golden Dragon Road, 1st Industrial Park of Dongcheng Dongguan China 500 (350/150) Footwear Sangyuan, 523119 Fujian Fuqing Huatai Footwear Co. Madden Intl. Ltd. Trading Lingjiao Village, Shangjing Town Fuqing Fujian China 360 (170/190) Footwear Ltd. Dolce Vita Intl. Nanyuan Knitting & Garments Co. South Asia Knitting Factory Ltd. Nanhua Industry District, Shengxin Town Nanan City Fujian China 604 (152/452) Sweaters Ltd. -

Official Gazette Vol. 49.Pdf

ສາທາລະນະລດັ ປະຊາທິປະໄຕ ປະຊາຊນົ ລາວ LAO PEOPLE’S DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC ກະຊວງ ວທິ ະຍາສາດ ແລະ ເຕັກໂນໂລຊ ີ ກມົ ຊບັ ສນິ ທາງປນັ ຍາ MINISTRY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY DEPARTMENT OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY ຈດົ ໝາຍເຫດທາງລດັ ຖະການ ກຽ່ ວກບັ ການເຜີຍແຜຜ່ ນົ ຂອງການຈດົ ທະບຽນ ຊບັ ສນິ ອດຸ ສາຫະກາ ຢ່ ສປປ ລາວ OFFICIAL GAZETTE OF INDUSTRIAL PROPERTY ສະບບັ ທີ (Vol.) 49 Official Gazette of Industrial Property Vol. 49, 09/2012 ສາລະບານ ພາກທີ່ I: ຜນົ ຂອງການຈດົ ທະບຽນເຄີ່ ອ ງໝາຍການຄາ້ ພາກທ II: ຜນົ ຂອງການຕີ່ ອາຍກຸ ານຈດົ ທະບຽນເຄີ່ ອ ງໝາຍການຄາ້ CONTENT Part I: Registration of Trademark Part II: Renewal of Trademark I Official Gazette of Industrial Property Vol. 49, 09/2012 ພາກທ I ຜນົ ຂອງການຈດົ ທະບຽນເຄີ່ ອ ງໝາຍການຄາ້ ຄາ ແນະນາ ກຽີ່ ວກບັ ລະຫດັ ຫຍ ້ (540) ເຄີ່ ອງໝາຍການຄາ້ (511) ໝວດຂອງສນິ ຄາ້ ແລະ ການບ ລິການ (210) ເລກທ ຄາ ຮອ້ ງ (220) ວນັ ທ ທີ່ ຍີ່ ນຄາ ຮອ້ ງ (731) ຊີ່ ແລະ ທີ່ ຢີ່ ຂອງຜຍ້ ີ່ ນ ຄາ ຮອ້ ງ (111) ເລກທ ໃບທະບຽນເຄີ່ ອງໝາຍການຄາ້ (180) ວນັ ໝດົ ອາຍຂຸ ອງໃບທະບຽນ Part I Registration of Trademark Introduction of Codes (540) Trademark (511) Classification of goods and services (Nice Classification) (210) Number of the application (220) Date of filing of the application (730) Name and Address of applicant (111) Number of the registration (180) Expiration date of the registration/renewal II Official Gazette of Industrial Property Vol. 49, 09/2012 ( 540 ) (511) 01 (210) No. 25716 (220) 01/02/2012 (732) Poodang 168 (Thailand) Co., Ltd. 34/6 Moo 1, Chaengwattana Road, Tambol Klongklue, Amphur Pakkat, Nonthaburi Province, Thailand (111) No. 25051 (180) 01/02/2022 ( 540 ) (511) 01 (210) No. 25717 (220) 01/02/2012 (732) Poodang 168 (Thailand) Co., Ltd. -

China National Accord Medicines Corporation Ltd

China National Accord Medicines Corporation Ltd. Semi-Annual Report 2020 August 2020 1 Section I. Important Notice, Contents and Interpretation Board of Directors, Supervisory Committee, all directors, supervisors and senior executives of China National Accord Medicines Corporation Ltd. (hereinafter referred to as the Company) hereby confirm that there are no any fictitious statements, misleading statements, or important omissions carried in this report, and shall take all responsibilities, individual and/or joint, for the reality, accuracy and completion of the whole contents. Lin Zhaoxiong, Principal of the Company, Gu Guolin, person in charger of accounting works and Wang Ying, person in charge of accounting organ (accounting principal) hereby confirm that the Financial Report of Semi- Annual Report 2020 is authentic, accurate and complete. Other directors attending the Meeting for annual report deliberation except for the followed: Name of director absent Title for absent director Reasons for absent Attorney Lian Wanyong Director Official business Li Dongjiu The Company plans not to pay cash dividends, bonus and carry out capitalizing of common reserves. 2 Contents Semi-Annual Report 2020..................................................................................................................2 Section I Important Notice, Contents and Interpretation.............................................................. 2 Section II Company Profile and Main Financial Indexes...............................................................5 -

CHSA HP2010.Pdf

The Hawai‘i Chinese: Their Experience and Identity Over Two Centuries 2 0 1 0 CHINESE AMERICA History&Perspectives thej O u r n a l O f T HE C H I n E s E H I s T O r I C a l s OCIET y O f a m E r I C a Chinese America History and PersPectives the Journal of the chinese Historical society of america 2010 Special issUe The hawai‘i Chinese Chinese Historical society of america with UCLA asian american studies center Chinese America: History & Perspectives – The Journal of the Chinese Historical Society of America The Hawai‘i Chinese chinese Historical society of america museum & learning center 965 clay street san francisco, california 94108 chsa.org copyright © 2010 chinese Historical society of america. all rights reserved. copyright of individual articles remains with the author(s). design by side By side studios, san francisco. Permission is granted for reproducing up to fifty copies of any one article for educa- tional Use as defined by thed igital millennium copyright act. to order additional copies or inquire about large-order discounts, see order form at back or email [email protected]. articles appearing in this journal are indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: History and Life. about the cover image: Hawai‘i chinese student alliance. courtesy of douglas d. l. chong. Contents Preface v Franklin Ng introdUction 1 the Hawai‘i chinese: their experience and identity over two centuries David Y. H. Wu and Harry J. Lamley Hawai‘i’s nam long 13 their Background and identity as a Zhongshan subgroup Douglas D. -

OMUFA Facility Arrears List Thursday, August 26, 2021

OMUFA Facility Arrears List Friday, September 10, 2021 The following facilities have not satisfied the annual Over-The-Counter (OTC) Monograph User Fee Program (OMUFA) facility fee(s) as required under section 744M of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act), as added by the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (or the “CARES Act”), under which FDA will assess and collect fees from submitters of OTC Monograph Order Requests (OMORs) as well as facility fees from qualifying manufacturers of OTC monograph drugs. The facility fee was due no later than May 10, 2021, for fiscal year (FY) 2021. If a facility does not pay the annual facility fee within 20 calendar days of the due date, the Agency will place the facility on a publicly available arrears list, and all OTC monograph drug products produced at that facility (or containing an ingredient manufactured at that facility) shall be deemed misbranded under section 502(ff) of the FD&C Act. Additionally, OMORs and meeting requests related to OMORs will not be accepted from persons, or their affiliate(s) in arrears (see section 744M(e) of the FD&C Act). We encourage you to seek verification from your business partners that all applicable fee(s) have been received in full by the Agency. If your records indicate that an FY 2021 OMUFA facility fee was previously submitted, please contact [email protected] and provide the following information: • Facility Name • Dun & Bradstreet (DUNS) number • FDA Establishment Identifier (FEI) Number • User Fee Payment I.D. Number (PIN) • Payment method, date, and amount Additionally, if you believe that your facility is not subject to OMUFA facility fees, please contact [email protected] and provide a brief explanation for your reasoning. -

Finding Your Chinese Roots

Finding your By Kate Bagnall www.katebagnall.com Chinese roots For Australians whose Chinese ancestors arrived in the Tips for tracing nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, tracing the family your Australian history back to China can be a real puzzle. family’s Chinese Whether you are simply curious about your Chinese origins origins or would like to visit your ancestor’s home in China, there are two things you need to know – your Chinese ancestor’s name in Chinese characters and their village and county of origin. Here you will find some suggestions for using Australian records to find these critical pieces of information. Chinese origins Most Chinese who arrived in Australia in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries came from the rural Pearl River Delta region of Guangdong province, south of the provincial capital of Guangzhou, north of Macau and inland from Hong Kong. A smaller number of Chinese migrants came from other parts of Guangdong province and from Fujian province (through the port of Xiamen, known historically as Amoy), as well as from other places such as Shanghai. This paper concentrates on Cantonese migrants who came from the Pearl River Delta. Cantonese migrants came from a number of different areas in the Pearl River Delta, including: • Sam Yup (Sanyi, meaning the ‘three districts’): Namhoi (Nanhai), Poonyu (Panyu) and Shuntak (Shunde) • Heungshan (Xiangshan), later known as Chungshan (Zhongshan) • Tongkun (Dongguan) • Tsengshing (Zengcheng) • Koyiu (Gaoyao) and Koming (Gaoming) • Sze Yup (Siyi, meaning the ‘four districts’): Sunwui (Xinhui), Sunning (Xinning) or Toishan (Taishan), Hoiping (Kaiping) and Yanping (Enping). The Cantonese migrants spoke a range of dialects including: standard Cantonese, Cantonese variations such as Shekki dialect, Longdu (Zhongshan Min) dialect, Sze Yup dialects such as Taishanese, and Hakka. -

Ceramic Tableware from China List of CNCA‐Certified Ceramicware

Ceramic Tableware from China June 15, 2018 List of CNCA‐Certified Ceramicware Factories, FDA Operational List No. 64 740 Firms Eligible for Consideration Under Terms of MOU Firm Name Address City Province Country Mail Code Previous Name XIAOMASHAN OF TAIHU MOUNTAINS, TONGZHA ANHUI HANSHAN MINSHENG PORCELAIN CO., LTD. TOWN HANSHAN COUNTY ANHUI CHINA 238153 ANHUI QINGHUAFANG FINE BONE PORCELAIN CO., LTD HANSHAN ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT ZONE ANHUI CHINA 238100 HANSHAN CERAMIC CO., LTD., ANHUI PROVINCE NO.21, DONGXING STREET DONGGUAN TOWN HANSHAN COUNTY ANHUI CHINA 238151 WOYANG HUADU FINEPOTTERY CO., LTD FINEOPOTTERY INDUSTRIAL DISTRICT, SOUTH LIUQIAO, WOSHUANG RD WOYANG CITY ANHUI CHINA 233600 THE LISTED NAME OF THIS FACTORY HAS BEEN CHANGED FROM "SIU‐FUNG CERAMICS (CHONGQING SIU‐CERAMICS) CO., LTD." BASED ON NOTIFICATION FROM CNCA CHONGQING CHN&CHN CERAMICS CO., LTD. CHENJIAWAN, LIJIATUO, BANAN DISTRICT CHONGQING CHINA 400054 RECEIVED BY FDA ON FEBRUARY 8, 2002 CHONGQING KINGWAY CERAMICS CO., LTD. CHEN JIA WAN, LI JIA TUO, BANAN DISTRICT, CHONGQING CHINA 400054 BIDA CERAMICS CO.,LTD NO.69,CHENG TIAN SI GE DEHUA COUNTY FUJIAN CHINA 362500 NONE DATIAN COUNTY BAOFENG PORCELAIN PRODUCTS CO., LTD. YONGDE VILLAGE QITAO TOWN DATIAN COUNTY CHINA 366108 FUJIAN CHINA DATIAN YONGDA ART&CRAFT PRODUCTS CO., LTD. NO.156, XIANGSHAN ROAD, JUNXI TOWN, DATIAN COUNTY FUJIAN 366100 DEHUA KAIYUAN PORCELAIN INDUSTRY CO., LTD NO. 63, DONGHUAN ROAD DEHUA TOWN FUJIAN CHINA 362500 THE LISTED ADDRESS OF THIS FACTORY HAS BEEN CHANGED FROM "MAQIUYANG XUNZHONG XUNZHONG TOWN, DEHUA COUNTY" TO THE NEW EAST SIDE, THE SECOND PERIOD, SHIDUN PROJECT ADDRESS LISTED ABOVE BASED ON NOTIFICATION DEHUA HENGHAN ARTS CO., LTD AREA, XUNZHONG TOWN, DEHUA COUNTY FUJIAN CHINA 362500 FROM THE CNCA AUTHORITY IN SEPTEMBER 2014 DEHUA HONGSHENG CERAMICS CO., LTD. -

Traceability | Together

TRUST | TRANSPARENCY | TRACEABILITY | TOGETHER SUPPLIER LIST COUNTRY SUPPLIER NAME SUPPLIER ADDRESS PRODUCTS LAST AUDIT NUMBER OF WORKERS BANGLEDESH Basicline International Ltd Bokran, Monipur, Mirzapur, Gazipur, Dhaka Cut & Sewn 13-Dec-18 1198 CHINA Binhai Clear Knitted Fashion Co., Ltd. 2~3F Shixun Building, No. 199, North Zhongshi Road, Dongkan Town, Binhai, Yancheng City, Jiangsu Cut & Sewn 12-Sep-18 86 Binhai Sales Co., Ltd Section 2, Batan Village, Batan Town, Binhai Coutry, Jiangsu Knit 31-Jul-18 338 Dongguan Cason Knitting Co Ltd Xiangyuan East Road, Shangtun Village, Liaobu Town, Dongguan , Guangdong Knit 14-Aug-18 1068 Dongguan Xin Neng Jin He Garment Co Ltd #1B, Yinghu Industrial Area, Qingxi Town, Dongguan, Guangdong Woven 27-Nov-18 100 Dongtai Sumeng Knitting Fashion Co., Ltd. No.11 Weft 2 Road, Economic Development Zone, Dongtai City, Jiangsu Cut & Sewn 18-Sep-18 223 Eurohai Garment Company Ltd. No.36 Tian peng Road,Fengxian Area,Shanghai Woven 15-Oct-18 37 Foshan Nanhai Shengli Leather Garment Co., Ltd. 4/F No.358, Jiang Bin Xin Qu, Jiu Jiang Town, Nanhai, Foshan, Guangdong Woven 20-Nov-18 65 Hangzhou Wonder Garment Ltd. Floor 2, Building 2, No. 10 Kanghui Road, Gongshu District, Hangzhou, Zhejiang Woven 25-Jul-18 136 Haolida fashion co.ltd Group 1,3 Sunliqiao Village, Xingdong Town, Tongzhou District, Nantong, Jiangsu Woven 26-Sep-18 203 Ivy Fashion Co. Ltd. No. 38 Sjjin Road, Yuanshanbei Village, Changping Town, Dongguan, Guang Dong Province, China Knit 15-Aug-18 244 Jiangsu Sunshine Garment 18th Taoxin RD, Xinqiao Town, Jiangyin City, Jiangsu Woven 7-Nov-18 526 Jiaxing Datang Garment Ltd Yuxin Town Industrial Park, Nanhu District, Jiaxing Cut & Sewn 2-May-18 96 Jiayu Fashion Co Ltd (Tongxiang ) Renmin Road No. -

![Him Mark Lai Papers, 1778-[On-Going] (Bulk 1970-1995)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0453/him-mark-lai-papers-1778-on-going-bulk-1970-1995-5480453.webp)

Him Mark Lai Papers, 1778-[On-Going] (Bulk 1970-1995)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt7r29q3gq No online items Finding Aid to the Him Mark Lai Papers, 1778-[on-going] (bulk 1970-1995) Processed by Jean Jao-Jin Kao, Yu Li, Janice Otani, Limin Fu, Yen Chen, Joy Hung, Lin Lin Ma, Zhuqing Xia and Mabel Yang The Ethnic Studies Library. 30 Stephens Hall #2360 University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-2360 Phone: (510) 643-1234 Fax: (510) 643-8433 Email: [email protected] URL: http://eslibrary.berkeley.edu © 2003 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the Him Mark Lai AAS ARC 2000/80 1 Papers, 1778-[on-going] (bulk 1970-1995) Finding Aid to the Him Mark Lai Papers, 1778-[on-going] (bulk 1970-1995) Collection number: AAS ARC 2000/80 The Ethnic Studies Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California Contact Information: The Ethnic Studies Library. 30 Stephens Hall #2360 University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-2360 Phone: (510) 643-1234 Fax: (510) 643-8433 Email: [email protected] URL: http://eslibrary.berkeley.edu/ Collection Processed By: Jean Jao-Jin Kao, Yu Li, Janice Otani, Limin Fu, Yen Chen, Joy Hung, Lin Lin Ma, Zhuqing Xia and Mabel Yang Date Completed: May 2003 Finding Aid written by: Jean Jao-Jin Kao, Janice Otani and Wei Chi Poon © 2003 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Him Mark Lai Papers, Date: 1778-[on-going] Date (bulk): (bulk 1970-1995) Collection number: AAS ARC 2000/80 Creator: Lai, H. Mark Extent: 130 Cartons, 61 Boxes, 7 Oversize Folders199.4 linear feet Repository: University of California, BerkeleyThe Ethnic Studies Library Berkeley, California 94720-2360 Abstract: The Him Mark Lai Papers are divided into four series: Research Files, Professional Activities, Writings, and Personal Papers. -

Sanctioned Entities Name of Firm & Address Date of Imposition of Sanction Sanction Imposed Grounds China Railway Constructio

Sanctioned Entities Name of Firm & Address Date of Imposition of Sanction Sanction Imposed Grounds China Railway Construction Corporation Limited Procurement Guidelines, (中国铁建股份有限公司)*38 March 4, 2020 - March 3, 2022 Conditional Non-debarment 1.16(a)(ii) No. 40, Fuxing Road, Beijing 100855, China China Railway 23rd Bureau Group Co., Ltd. Procurement Guidelines, (中铁二十三局集团有限公司)*38 March 4, 2020 - March 3, 2022 Conditional Non-debarment 1.16(a)(ii) No. 40, Fuxing Road, Beijing 100855, China China Railway Construction Corporation (International) Limited Procurement Guidelines, March 4, 2020 - March 3, 2022 Conditional Non-debarment (中国铁建国际集团有限公司)*38 1.16(a)(ii) No. 40, Fuxing Road, Beijing 100855, China *38 This sanction is the result of a Settlement Agreement. China Railway Construction Corporation Ltd. (“CRCC”) and its wholly-owned subsidiaries, China Railway 23rd Bureau Group Co., Ltd. (“CR23”) and China Railway Construction Corporation (International) Limited (“CRCC International”), are debarred for 9 months, to be followed by a 24- month period of conditional non-debarment. This period of sanction extends to all affiliates that CRCC, CR23, and/or CRCC International directly or indirectly control, with the exception of China Railway 20th Bureau Group Co. and its controlled affiliates, which are exempted. If, at the end of the period of sanction, CRCC, CR23, CRCC International, and their affiliates have (a) met the corporate compliance conditions to the satisfaction of the Bank’s Integrity Compliance Officer (ICO); (b) fully cooperated with the Bank; and (c) otherwise complied fully with the terms and conditions of the Settlement Agreement, then they will be released from conditional non-debarment. If they do not meet these obligations by the end of the period of sanction, their conditional non-debarment will automatically convert to debarment with conditional release until the obligations are met. -

Supplier List

TRUST TRANSPARENCY TRACEABILITY TOGETHER SUPPLIER LIST COUNTRY SUPPLIER NAME SUPPLIER ADDRESS PRODUCTS LAST AUDIT NUMBER OF WORKERS BANGLADESH Arabi Fashion Limited Bokran, Monipur, Mirzapur, Gazipur, Dhaka Cut & Sew 22-Dec-2016 1160 CHINA Binhai Clear Knitted Fashion Co., Ltd. North of Zhongshi Road #199, Binhai city Cut & Sew 19-Sep-2017 154 Binhai Sales Co., Ltd. Section 2, Batan Village, Batan Town, Binhai County, Yancheng City, Jiangsu Province Knit 17-Aug-2017 327 Changzhou Sincere Fashion Co. Ltd No. 136 North Qingyang Road, Changzhou, Jiangsu Woven 4-Sep-2017 370 Changzhou Yunjin Garment Co Ltd No. 8 Industry Development Zone, Hubin Road, Niutang Town, Changzhou City, Jiangsu Woven 3-Nov-2017 125 Dongguan Cason Knit Co., Ltd No. 61 East Xiangyuan Road, Shangtun Vilage, Liaobu Town, Dongguan, Guangdong Knit 22-Mar-2017 1150 Dongguan Huahao Garment Factory Floor 3, Yangxin Road No.393, Dalang Town, Dongguan, Guangdong Knit 8-Dec-2017 42 Dongguan Ivy Fashion Co. Ltd No. 38, Sijin Road, Yuanshanbei Village, Changping Town, Dongguan, Guangdong Knit 8-Jun-2017 275 Dongguan Xin Neng Jinhe Garment Ltd #18, Ying Hu Industrial Area, Qingxi Town, Dongguan Woven 10-Aug-2017 126 Dongtai Sumeng Knitting Fashion Ltd No.11 Weft 2 Road, Economic Development Zone, Dongtai , Jiangsu Cut & Sewn 20-Sep-2017 280 Eurohai Garment Company Ltd. No.36 Tian peng Road,Fengxian Area,Shanghai Woven 29-Sep-2017 46 Hangzhou Wonder Garment Ltd. Floor 2, Building 2, No. 10 Kanghui Road, Gongshu District, Hangzhou, Zhejiang Woven 12-Jul-2017 149 Jiaxing Datang Garment Ltd Yuxin Town Industrial Park, Nanhu District, Jiaxing Cut & Sew 24-Apr-2017 133 Jiayu Fashion Co Ltd (Tongxiang ) Renmin Road No.