391 Faction with the Reply of That Republic to the Effect That It Referred

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

50000132.Pdf

EDITORIAL EARTH Lic. José Ruperto Arce (Coordinador) Russo, Ricardo O. Reducción y mitigación de la pobreza en la Región Huetar Atlántica [Documento electrónico] / Ricardo O Russo y Eliécer Ureña… 1º ed.- Guácimo, CR: Editorial EARTH, 2006. 24 p. : il. Serie Documentos Técnicos, No. 4. ISBN 1. MITIGACIÓN DE LA POBREZA. 2. POBREZA. 3. MERCADO DEL TRABAJO. 4. EMPLEO. 5. REGIÓN HUETAR ATLÁNTICA. EARTH. I. Russo, Ricardo O. II. Ureña, Eliécer. Universidad EARTH Agosto, 2006. Las Mercedes de Guácimo, Limón Costa Rica Apartado Postal 4442-1000 San José, Costa Rica Teléfono 506 - 713 0000 • Fax 506 - 713 0184 Universidad de Costa Rica Universidad EARTH TABLA DE CONTENIDO 1. INTRODUCCIÓN………………………………………………………1 2. EL ESTUDIO DE LA POBREZA EN COSTA RICA ……………….1 3. LA POBREZA EN LA RHA…………………………………..………7 3.1. El ingreso y el empleo.………………………………………...7 3.2. Los servicios………….………………………………..….…..10 3.3. La oferta institucional….……………………………………...14 4. CONCLUSIONES Y RECOMENDACIONES …………… …….18 4.1. Conclusiones………………………………………….……….18 4.2. Recomendaciones………………………………………..…….19 4.3. Bibliografía……………………………………………..……...23 Universidad de Costa Rica Universidad EARTH Reducción y mitigación de la pobreza en la Región Huetar Atlántica - Ricardo O. Russo y Eliécer Ureña Reducción y mitigación de la pobreza en la Región Huetar Atlántica Ricardo O. Russo y Eliécer Ureña 1. Introducción Este análisis de la pobreza en la Región Huetar Atlántica (RHA) y sus alternativas de reducirla y mitigarla es parte de un estudio sobre el empleo, el ingreso y el bienestar de la población realizada por los autores como apoyo regional auspiciado por el Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo (BID). Se basa en parte en los informes sobre el mercado laboral, la capacidad y potencial de la economía regional, y los proyectos y propuestas presentado por instituciones, programas y organizaciones en la RHA durante la elaboración del estudio. -

Más Información De La Agencia

Dirección Nacional de Extensión Agropecuaria CARACTERIZACIÓN DEL ÁREA DE INFLUENCIA DE LA AGENCIA DE EXTENSIÓN AGROPECUARIA 1. DATOS GENERALES DE LA AGENCIA DE EXTENSIÓN AGROPECUARIA 1.1. Nombre de la AEA: Cahuita 1.2. Teléfono: 21056341 1.3. Ubicación Física (Dirección Exacta): Contiguo al Salón Comunal 1.4. Nombre de la Jefatura: Keneth Bolivar Quiel, correo [email protected] 1.5. Recurso humano (Extensionistas, Apoyo secretarial, Apoyo administrativo, misceláneo) RECURSO HUMANO DE LA AGENCIA Nombre Cargo Especialidad Correo Keneth Bolivar Quiel Jefe Fitotecnia [email protected] Yuri Payan Molano Secretaria Secretariado [email protected] Luis A. Fuentes Cornejo Técnico Técnico medio [email protected] Alfredo López Martínez Técnico Zootecnia [email protected] Kenet Bolívar Quiel Técnico Profesional Generalista [email protected] Alberto Rojas Bravo Técnico Profesional Generalista [email protected] Mapa Tomado del Estudio para el plan cantonal de desarrollo humano y plan estratégico del cantón de Talamanca. 2014-2024. Fuente: Estado de la Nación. Indicadores cantonales 2000/2011 Provincia de Limón. Dirección Nacional de Extensión Agropecuaria Tomado del Plan de Desarrollo Rural Territorial Talamanca-Valle la Estrella. 2015-2020. La Agencia de Extensión Agropecuaria de Cahuita está a cargo del Cantón de Talamanca y del Distrito de Valle de la Estrella. Dirección Nacional de Extensión Agropecuaria 2. INFORMACIÓN DIAGNÓSTICA DEL ÁREA DE INFLUENCIA 2.1. Caracterización socioeconómica 2.1.1. Información político administrativa y Comunidades del Área de Influencia de la Agencia *Tomado de: Ministerio de Planificación Nacional y Política Económica. Área de Análisis del Desarrollo. Índice de desarrollo social 2017 / Ministerio de Planificación Nacional y Política Económica. -

Financing Plan, Which Is the Origin of This Proposal

PROJECT DEVELOPMENT FACILITY REQUEST FOR PIPELINE ENTRY AND PDF-B APPROVAL AGENCY’S PROJECT ID: RS-X1006 FINANCINGIDB PDF* PLANIndicate CO-FINANCING (US$)approval 400,000date ( estimatedof PDFA ) ** If supplemental, indicate amount and date GEFSEC PROJECT ID: GEFNational ALLOCATION Contribution 60,000 of originally approved PDF COUNTRY: Costa Rica and Panama ProjectOthers (estimated) 3,000,000 PROJECT TITLE: Integrated Ecosystem Management of ProjectSub-Total Co-financing PDF Co- 960,000 the Binational Sixaola River Basin (estimated)financing: 8,500,000 GEF AGENCY: IDB Total PDF Project 960,000 OTHER EXECUTING AGENCY(IES): Financing:PDF A* DURATION: 8 months PDF B** (estimated) 500,000 GEF FOCAL AREA: Biodiversity PDF C GEF OPERATIONAL PROGRAM: OP12 Sub-Total GEF PDF 500,000 GEF STRATEGIC PRIORITY: BD-1, BD-2, IW-1, IW-3, EM-1 ESTIMATED STARTING DATE: January 2005 ESTIMATED WP ENTRY DATE: January 2006 PIPELINE ENTRY DATE: November 2004 RECORD OF ENDORSEMENT ON BEHALF OF THE GOVERNMENT: Ricardo Ulate, GEF Operational Focal Point, 02/27/04 Ministry of Environment and Energy (MINAE), Costa Rica Ricardo Anguizola, General Administrator of the 01/13/04 National Environment Authority (ANAM), Panama This proposal has been prepared in accordance with GEF policies and procedures and meets the standards of the GEF Project Review Criteria for approval. IA/ExA Coordinator Henrik Franklin Janine Ferretti Project Contact Person Date: November 8, 2004 Tel. and email: 202-623-2010 1 [email protected] PART I - PROJECT CONCEPT A - SUMMARY The bi-national Sixaola river basin has an area of 2,843.3 km2, 19% of which are in Panama and 81% in Costa Rica. -

DRAFT Environmental Profile the Republic Costa Rica Prepared By

Draft Environmental Profile of The Republic of Costa Rica Item Type text; Book; Report Authors Silliman, James R.; University of Arizona. Arid Lands Information Center. Publisher U.S. Man and the Biosphere Secretariat, Department of State (Washington, D.C.) Download date 26/09/2021 22:54:13 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/228164 DRAFT Environmental Profile of The Republic of Costa Rica prepared by the Arid Lands Information Center Office of Arid Lands Studies University of Arizona Tucson, Arizona 85721 AID RSSA SA /TOA 77 -1 National Park Service Contract No. CX- 0001 -0 -0003 with U.S. Man and the Biosphere Secretariat Department of State Washington, D.C. July 1981 - Dr. James Silliman, Compiler - c /i THE UNITEDSTATES NATION)IL COMMITTEE FOR MAN AND THE BIOSPHERE art Department of State, IO /UCS ria WASHINGTON. O. C. 2052C An Introductory Note on Draft Environmental Profiles: The attached draft environmental report has been prepared under a contract between the U.S. Agency for International Development(A.I.D.), Office of Science and Technology (DS /ST) and the U.S. Man and the Bio- sphere (MAB) Program. It is a preliminary review of information avail- able in the United States on the status of the environment and the natural resources of the identified country and is one of a series of similar studies now underway on countries which receive U.S. bilateral assistance. This report is the first step in a process to develop better in- formation for the A.I.D. Mission, for host country officials, and others on the environmental situation in specific countries and begins to identify the most critical areas of concern. -

Sixaola, Talamanca – Limón (34-BID)

MINISTERIO DE AGRICULTURA Y GANADERIA Unidad Coordinadora Programa de Desarrollo Sostenible de la Cuenca Binacional del Río Sixaola Telefax: 2755-0268 Cahuita, Talamanca Producción y Turismo Ecológicos Asociación Microempresarial de Productores y Productoras Agropecuarias de Gandoca – Sixaola, Talamanca – Limón (34-BID) PROGRAMA DE DESARROLLO SOSTENIBLE DE LA CUENCA BINACIONAL DEL RÍO SIXAOLA Elaboró: Rodolfo A. Fallas Castro. Colaboró: Andrea Mora, Coordinador Técnico CD Cahuita - Sixaola Febrero 2012 1 MINISTERIO DE AGRICULTURA Y GANADERIA Unidad Coordinadora Programa de Desarrollo Sostenible de la Cuenca Binacional del Río Sixaola Telefax: 2755-0268 Cahuita, Talamanca Tabla de contenidos 1 Nombre del Proyecto .................................................................................. 5 1.1 Resumen Ejecutivo ........................................................................................ 5 2 Datos Básicos .............................................................................................. 6 3 Ubicación del Proyecto ............................................................................... 6 4 Descripción de beneficiarios ...................................................................... 6 5 Antecedentes y Justificación ..................................................................... 7 5.1 Naturaleza del proyecto ................................................................................. 8 6 Objetivos ..................................................................................................... -

Critical Beaches Due to Coastal Erosion in the Caribbean South of Costa Rica, During the Period 2005-2016

Revista Geográfica de América Central ISSN: 1011-484X ISSN: 2215-2563 [email protected] Universidad Nacional Costa Rica Critical beaches due to coastal erosion in the Caribbean south of Costa Rica, during the period 2005-2016 Barrantes-Castillo, Gustavo; Arozarena-Llopis, Isabel; Sandoval-Murillo, Luis Fernando; Valverde- Calderón, José Francisco Critical beaches due to coastal erosion in the Caribbean south of Costa Rica, during the period 2005-2016 Revista Geográfica de América Central, vol. 1, no. 64, 2020 Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=451762295005 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15359/rgac.64-1.5 REVGEO se encuentra bajo la licencia https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/deed.es This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International. PDF generated from XML JATS4R by Redalyc Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Gustavo Barrantes-Castillo, et al. Critical beaches due to coastal erosion in the Caribbean south ... Estudios de Caso Critical beaches due to coastal erosion in the Caribbean south of Costa Rica, during the period 2005-2016 Playas críticas por erosión costera en el caribe sur de Costa Rica, durante el periodo 2005-2016 Gustavo Barrantes-Castillo DOI: https://doi.org/10.15359/rgac.64-1.5 Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica Redalyc: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa? [email protected] id=451762295005 Isabel Arozarena-Llopis Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica [email protected] Luis Fernando Sandoval-Murillo Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica [email protected] José Francisco Valverde-Calderón Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica [email protected] Received: 29 January 2019 Accepted: 07 May 2019 Abstract: Since 2010, the local press has been reporting an accelerated process of erosion on the sandy beaches of the Costa Rican Caribbean coast, it has even been documented within protected areas. -

United Nations Development Programme Project Title

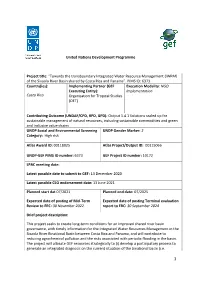

ƑPROJECT INDICATOR 10 United Nations Development Programme Project title: “Towards the transboundary Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) of the Sixaola River Basin shared by Costa Rica and Panama”. PIMS ID: 6373 Country(ies): Implementing Partner (GEF Execution Modality: NGO Executing Entity): Implementation Costa Rica Organisation for Tropical Studies (OET) Contributing Outcome (UNDAF/CPD, RPD, GPD): Output 1.4.1 Solutions scaled up for sustainable management of natural resources, including sustainable commodities and green and inclusive value chains UNDP Social and Environmental Screening UNDP Gender Marker: 2 Category: High risk Atlas Award ID: 00118025 Atlas Project/Output ID: 00115066 UNDP-GEF PIMS ID number: 6373 GEF Project ID number: 10172 LPAC meeting date: Latest possible date to submit to GEF: 13 December 2020 Latest possible CEO endorsement date: 13 June 2021 Planned start dat 07/2021 Planned end date: 07/2025 Expected date of posting of Mid-Term Expected date of posting Terminal evaluation Review to ERC: 30 November 2022. report to ERC: 30 September 2024 Brief project description: This project seeks to create long-term conditions for an improved shared river basin governance, with timely information for the Integrated Water Resources Management in the Sixaola River Binational Basin between Costa Rica and Panama, and will contribute to reducing agrochemical pollution and the risks associated with periodic flooding in the basin. The project will allocate GEF resources strategically to (i) develop a participatory process to generate an integrated diagnosis on the current situation of the binational basin (i.e. 1 Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis - TDA) and a formal binding instrument adopted by both countries (i.e. -

Proceedings of the Twenty-Ninth Annual Symposium on Sea Turtle Biology and Conservation

NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-SEFSC-630 PROCEEDINGS OF THE TWENTY-NINTH ANNUAL SYMPOSIUM ON SEA TURTLE BIOLOGY AND CONSERVATION 17 to 19 February 2009 Brisbane, Queensland, Australia Compiled by: Lisa Belskis, Mike Frick, Aliki Panagopoulou, ALan Rees, & Kris Williams U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration NOAA Fisheries Service Southeast Fisheries Science Center 75 Virginia Beach Drive Miami, Florida 33149 May 2012 NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-SEFSC-630 PROCEEDINGS OF THE TWENTY-NINTH ANNUAL SYMPOSIUM ON SEA TURTLE BIOLOGY AND CONSERVATION 17 to 19 February 2009 Brisbane, Queensland, Australia Compiled by: Lisa Belskis, Mike Frick, Aliki Panagopoulou, ALan Rees, Kris Williams U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE John Bryson, Secretary NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION Dr. Jane Lubchenco, Under Secretary for Oceans and Atmosphere NATIONAL MARINE FISHERIES SERVICE Samuel Rauch III, Acting Assistant Administrator for Fisheries May 2012 This Technical Memorandum is used for documentation and timely communication of preliminary results, interim reports, or similar special-purpose information. Although the memoranda are not subject to complete formal review, editorial control or detailed editing, they are expected to reflect sound professional work. NOTICE The NOAA Fisheries Service (NMFS) does not approve, recommend or endorse any proprietary product or material mentioned in this publication. No references shall be made to NMFS, or to this publication furnished by NMFS, in any advertising or sales promotion which would indicate or imply that NMFS approves, recommends or endorses any proprietary product or material herein or which has as its purpose any intent to cause directly or indirectly the advertised product to be use or purchased because of NMFS promotion. -

Diagnóstico De La Situación Turística De Los Actores Locales Y Las

(SINAC, 2014) PROYECTO FORTALECIMIENTO DEL PROGRAMA DE TURISMO EN ÁREAS DIAGNÓSTICO DE LA SILVESTRES PROTEIGIDAS (BID-TURISMO) SITUACIÓN TURÍSTICA DE Identificación de Oportunidades y Encadenamientos Turísticos Productivos en las LOS ACTORES LOCALES Y comunidades que se localizan en el área de influencia de las Áreas Silvestres Protegidas LAS COMUNIDADES (ASP) que forman parte del Proyecto Fortalecimiento del Programa de Turismo en ALEDAÑAS AL PARQUE ASP, vinculadas con los productos turísticos contemplados en los Planes de Turismo de dichas ASP. NACIONAL CAHUITA ELABORADO POR: COMUNIDADES DE: Cahuita, Carbón I, Carbón II, COOPRENA R.L. Hone Creek, Comadre, Borbón, San Rafael, Punta de Riel, Puerto Viejo. ÍNDICE Índice de Cuadros ................................................................................................... 3 Índice de Figuras…………………………………………………………………………..4 Índice de Gráficos…………………………………………………………………………5 Lista de Acrónimos .................................................................................................. 5 Introducción ............................................................................................................. 6 Capítulo I. Información General del Parque Nacional Cahuita y las comunidades que se ubican en el área de influencia. ....................................... 8 Ubicación Geográfica ......................................................................................... 10 - Coordenadas ............................................................................................. -

Caribbean Costa Rica Mission

Image not found or type unknown Caribbean Costa Rica Mission RENÉ MARTÍNEZ ALVARADO René Martínez Alvarado, B.A. (Central American Adventist University, Alajuela, Costa Rica), is a district pastor and departmental minister of personal ministries and communications of the Caribbean Mission. He has served the church for 17 years as a district pastor, ministries department director, and area coordinator. He is married to Stephanie Alfaro and has a son. Caribbean Costa Rica Mission is located in the province of Limón and includes the territory of Limón, the canton of Turrialba in the province of Cartago, and the canton of Sarapiquí in the province of Heredia. The mission is located at the east end of the country. It shares borders in the north with the Republic of Nicaragua, in the northeast with the Caribbean Sea, in the west with Heredia, Cartago, and San José, and in the southwest with Puntarenas and Panamá. 1 The province is rich in diversity of cultures, ethnicities, and languages: English, Spanish, Creole English, Bribri, Kabecar, and others. In 1872, the construction of the railroad in the Costa Rican Atlantic led to the arrival of Jamaican workers with Afro-American culture and British influences, giving Limón its distinctive limonense folklore.2 In the 2011 National Population and Housing Census, the population of Limón province was 386,862 inhabitants. Some main activities included the cultivation of bananas, pejibaye, cocoa, grains, and fruits; the raising of livestock; fishing; and tourism, which included nature reserves and national parks.3 Some of Limón’s sources of economy include JAPDEVA (Junta de Administración Portuaria y de Desarrollo Económico de la Vertiente Atlántica) Port and APM Terminal. -

La Côte Caraïbe Du Costa Rica

2 LA CÔTE CARAÏBE NICARAGUA 0 10 20km R Toro ío San Juan Río HEREDIA Refugio Nacional de Fauna Silvestre Barra del Colorado R lorado Barra del í o ó o C N Puerto Viejo Colorado ip r de Sarapiquí ir h C o í o i R c c u u S S o o í R Las Horquetas M Río Frio Tortuguero Tortugue ío ro Cariari R Agua Fría e r Rita Cerro Roxana Tortuguero Parque Nacional 32 d Zancudo Tortuguero Guápiles e Jiménez Villa Franca Siete s Jardín Botánico Guácimo Las Cusingas Río Jiménez Jaloba C Pocora Suerre Germania Parismina a o R r Rí ev ent n azó a Cairo Río Pacuare Monumento ï Santa Nacional Siquirres San Rafael Cruz b Guayabo Pacuarito Lajas 10 e Turrialba Pacuare Juan Nature Reserve Viñas s Peralta Batán Pavones Matina 32 CARTAGO Saborio Pejibaye La Suiza Reserva Indígena Tuís Barbilla Platanillo PortetePortete Playa Bonita Piuta Refugio Nacional Moín de Fauna Silvestre Puerto Limón Tapantí Reserva Indígena Isla Uvita ico Alto Y Bajo nt tlá Chirripó A el d pó Cerro Blanco rri LIMÓN hi (3800m) C 36 Parque Nacional Reserva Chirripó Indígena Tayní Cerro Chirripó (3819m) C Cerro Terbi o r Reserva (3760m) d Indígena i l Reserva Biológica Penshurst Parque l e Telire Nacional r a Hitoy Cerere Playa Negra Cahuita d Playa Chiquita e Bocuares R T ío a T Playa Blanca Cahuita Parque l a eli m vé Comadre Puerto Vargas Internacional a n La Amistad c a Playa Negra Uatsi Territorio indígeno Bribrí Talamanca-Bribrí Chase Puerto Viejo de Talamanca Bratsi P Playa Salsa Brava u Reserva Katsi n Playa Cocles ta Indígena U Playa Chiquita Ujarrás Yorkin Territorio indígeno va Kéköldi Refugio Nacional de Vida Silvestre Buenos Reserva R Margarita Gandoca-Manzanillo Aires Indígena ío S Salitre i x Manzanillo a o l Reserva PANAMÁ a Indígena Cabagra Sixaola guidesulysse.com 3 LA CÔTE CARAÏBE NICARAGUA 0 10 20km Le nord de la côte R Toro ío San Juan p. -

N.° 1920-E11-2020. Tribunal Supremo De Elecciones

N.° 1920-E11-2020. TRIBUNAL SUPREMO DE ELECCIONES. San José, a las catorce horas y quince minutos del diecisiete de marzo de dos mil veinte. Declaratoria de elección de sindicaturas y concejalías de distrito del cantón Talamanca de la provincia Limón, para el período comprendido entre el primero de mayo de dos mil veinte y el treinta de abril de dos mil veinticuatro. RESULTANDO 1.- Que de conformidad con lo establecido en el decreto n.° 19-2019, publicado en La Gaceta n.° 194 del catorce de octubre de dos mil diecinueve, este Tribunal convocó a todos los ciudadanos inscritos como electores en el Departamento Electoral del Registro Civil para que, ejerciendo el derecho fundamental al sufragio en votación directa y secreta, concurrieran a las respectivas juntas receptoras de votos el día domingo dos de febrero de dos mil veinte, a fin de que procedieran a elegir alcaldías, vicealcaldías primeras y segundas, regidurías propietarias y suplentes, sindicaturas propietarias y suplentes, concejalías de distrito propietarias y suplentes, concejalías municipales de distrito propietarias y suplentes en los lugares que corresponda, así como intendencias y viceintendencias de este último órgano, en los términos establecidos en la referida convocatoria. 2.- Que para la elección de sindicaturas y concejalías de distrito del cantón Talamanca de la provincia Limón, los partidos políticos que se indicará inscribieron en el Registro Electoral sus respectivas candidaturas. 3.- Que la respectiva votación se celebró el día domingo dos de febrero de dos mil veinte, fecha en la cual los electores sufragaron ante las respectivas juntas receptoras de votos, luego de lo cual este Tribunal procedió a realizar el escrutinio definitivo de los votos emitidos.