Contests Over the Local Meaning of Femininities and Local Class and Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

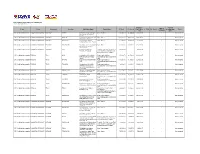

List of KALAHI-CIDSS Subprojects - MAKILAHOK As of February 01, 2019

List of KALAHI-CIDSS Subprojects - MAKILAHOK as of February 01, 2019 Estimated Physical Date of Region Province Municipality Barangay Sub-Project Name Project Type KC Grant LCC Amount Total Project No. Of HHsDate Started Accomplishme Status Completion Cost nt (%) CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA ANABEL Construction of One Unit One School Building 1,181,886.33 347,000.00 1,528,886.33 / / Not yet started Storey Elementary School Building CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA BEKIGAN Construction of Sumang-Paitan Water System 1,061,424.62 300,044.00 1,361,468.62 / / Not yet started Village Water System CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA BELWANG Construction of Pikchat- Water System 471,920.92 353,000.00 824,920.92 / / Not yet started Pattiging Village Water System CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA SACASACAN Rehabilitation of Penged Maballi- Water System 312,366.54 845,480.31 1,157,846.85 / / Not yet started Sacasshak Village Water Supply System CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA SACLIT Improvement of Wetig- Footpath / Foot Trail / Access Trail 931,951.59 931,951.59 / / Not yet started Takchangan Footpath (may include box culvert/drainage as a component for Footpath) CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]IFUGAO TINOC AHIN Construction of 5m x 1000m Road (may include box 251,432.73 981,708.84 1,233,141.57 / / Not yet started FMR Along Telep-Awa-Buo culvert/drainage as a component for Section road) -

JOSELINE “JOYCE” P. NIWANE Assistant Secretary for Policy and Plans DSWD-Central Office Batasan Pambansa Complex, Constitution Hills Quezon City

JOSELINE “JOYCE” P. NIWANE Assistant Secretary for Policy and Plans DSWD-Central Office Batasan Pambansa Complex, Constitution Hills Quezon City Personal Information Date of Birth: April 3, 1964 Place of Birth: Baguio City Marital Status: Single Parents: COL. Francisco Niwane(Ret) Mrs. Adela P. Niwane Education Elementary: Holy Family Academy, Baguio City 1971-1977 High School: Holy Family Academy, Baguio City 1977-1981 College: Saint Louis University, Baguio City 1982-1985 Post Education: 1. University of the Philippines (1989-1990) - Masters in Public Administration 2. University of Washington, Seattle, USA ( 2001-2002) -Post Graduate in Public Policy and Social Justice 3. Saint Mary’s University (2005-2006) - Masters in Public Administration AWARDS/ FELLOWSHIPS RECEVEIVED: 1986 : “Merit of Valor” Award – World Vision International 1996 : 1st Provincial AWARD OF MERIT – Provincial Government of Ifugao 1997 : Dangal ng Bayan Awardee - CSC and Pres. Fidel V. Ramos 1998 : Model Public Servant Awardee of the Year – KILOSBAYAN AND GMA 7 1998 : Outstanding Cordillera Woman of the Year – Midland Courier 1998 : 1st National Congress of Honor Awardee 2001 : Ifugao Achievers Award - Provincial Government of Ifugao 2001-2002 : Hubert Humphrey Fellowship Program/Fulbright- United States of America Government 2013 : Best Provincial Social Welfare and Dev’t. Officer – DSWD-CAR 2015 : Galing Pook Award - DILG 2016 : Gawad Gabay : Galing sa Paggabay sa mga Bata para sa Magandang Buhay “ Champion of Positive and Non-violent discipline for the Filipino -

Pdf | 308.16 Kb

2. Damaged Infrastructure and Agriculture (Tab D) Total Estimated Cost of Damages PhP 411,239,802 Infrastructure PhP 29,213,821.00 Roads & Bridges 24,800,000.00 Transmission Lines 4,413,821.00 Agriculture 382,025,981.00 Crops 61,403,111.00 HVCC 5,060,950.00 Fisheries 313,871,920.00 Facilities 1,690,000.00 No report of damage on school buildings and health facilities as of this time. D. Emergency Incidents Monitored 1. Region II a) On or about 10:00 AM, 08 May 2009, one (1) ferry boat owned by Brgy Captain Nicanor Taguba of Gagabutan, Rizal, bound to Cambabangan, Rizal, Cagayan, to attend patronal fiesta with twelve (12) passengers on board, capsized while crossing the Matalad River. Nine (9) passengers survived while three (3) are still missing identified as Carmen Acasio Anguluan (48 yrs /old), Vladimir Acasio Anguluan (7 yrs /old) and Mac Dave Talay Calibuso (5 yrs/old), all from Gagabutan East Rizal, Cagayan. The 501st Infantry Division (ID) headed by Col. Remegio de Vera, PNP personnel and some volunteers from Rizal, Cagayan conducted search and rescue operations. b) In Nueva Vizcaya, 31 barangays were flooded: Solano (16), Bagabag (5), Bayombong (4), Bambang (4), in Dupax del Norte (1) and in Dupax del Sur (1). c) Barangays San Pedro and Manglad in Maddela, Quirino were isolated due to flooding. e) The low-lying areas of Brgys Mabini and Batal in Santiago City, 2 barangays in Dupax del Norte and 4 barangays in Bambang were rendered underwater with 20 families evacuated at Bgy Mabasa Elementary School. -

School Name Region Province City of Lamitan Division District 29 30 31 32 33

Batch Batch Batch Batch Batch School Name Region Province City of Lamitan Division District 29 30 31 32 33 135740 Aguinaldo Central School CAR Ifugao Aguinaldo Ifugao Aguinaldo 1 0 0 0 0 135741 Awayan ES CAR Ifugao Aguinaldo Ifugao Aguinaldo 1 0 0 0 0 135742 Awayan ES - Annex CAR Ifugao Aguinaldo Ifugao Aguinaldo 1 0 0 0 0 135744 Butac ES CAR Ifugao Aguinaldo Ifugao Aguinaldo 1 0 0 0 0 135746 Chalalo ES CAR Ifugao Aguinaldo Ifugao Aguinaldo 1 0 0 0 0 135747 Chalalo ES - Annex CAR Ifugao Aguinaldo Ifugao Aguinaldo 1 0 0 0 0 135748 Damag ES CAR Ifugao Aguinaldo Ifugao Aguinaldo 1 0 0 0 0 135749 Galonogon ES CAR Ifugao Aguinaldo Ifugao Aguinaldo 1 0 0 0 0 135751 Halag ES CAR Ifugao Aguinaldo Ifugao Aguinaldo 1 0 0 0 0 135754 Itab ES CAR Ifugao Aguinaldo Ifugao Aguinaldo 1 0 0 0 0 135757 Manaot ES CAR Ifugao Aguinaldo Ifugao Aguinaldo 1 0 0 0 0 135758 Monggayang ES CAR Ifugao Aguinaldo Ifugao Aguinaldo 1 0 0 0 0 135759 Nepojnoc PS CAR Ifugao Aguinaldo Ifugao Aguinaldo 1 0 0 0 0 135760 Pojnaan ES CAR Ifugao Aguinaldo Ifugao Aguinaldo 1 0 0 0 0 135762 Ubao ES CAR Ifugao Aguinaldo Ifugao Aguinaldo 1 0 0 0 0 135763 Alfonso Lista CS CAR Ifugao Alfonso Lista (Potia) Ifugao Alfonso Lista I 1 0 0 0 0 135764 Balligi ES CAR Ifugao Alfonso Lista (Potia) Ifugao Alfonso Lista I 1 0 0 0 0 135765 Bangar ES CAR Ifugao Alfonso Lista (Potia) Ifugao Alfonso Lista II 1 0 0 0 0 135766 Busilac ES CAR Ifugao Alfonso Lista (Potia) Ifugao Alfonso Lista I 1 0 0 0 0 135767 Calimag ES CAR Ifugao Alfonso Lista (Potia) Ifugao Alfonso Lista II 1 0 0 0 0 135768 Calupaan -

Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population BATANES

2010 Census of Population and Housing Batanes Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population BATANES 16,604 BASCO (Capital) 7,907 Ihubok II (Kayvaluganan) 2,103 Ihubok I (Kaychanarianan) 1,665 San Antonio 1,772 San Joaquin 392 Chanarian 334 Kayhuvokan 1,641 ITBAYAT 2,988 Raele 442 San Rafael (Idiang) 789 Santa Lucia (Kauhauhasan) 478 Santa Maria (Marapuy) 438 Santa Rosa (Kaynatuan) 841 IVANA 1,249 Radiwan 368 Salagao 319 San Vicente (Igang) 230 Tuhel (Pob.) 332 MAHATAO 1,583 Hanib 372 Kaumbakan 483 Panatayan 416 Uvoy (Pob.) 312 SABTANG 1,637 Chavayan 169 Malakdang (Pob.) 245 Nakanmuan 134 Savidug 190 Sinakan (Pob.) 552 Sumnanga 347 National Statistics Office 1 2010 Census of Population and Housing Batanes Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population UYUGAN 1,240 Kayvaluganan (Pob.) 324 Imnajbu 159 Itbud 463 Kayuganan (Pob.) 294 National Statistics Office 2 2010 Census of Population and Housing Cagayan Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population CAGAYAN 1,124,773 ABULUG 30,675 Alinunu 1,269 Bagu 1,774 Banguian 1,778 Calog Norte 934 Calog Sur 2,309 Canayun 1,328 Centro (Pob.) 2,400 Dana-Ili 1,201 Guiddam 3,084 Libertad 3,219 Lucban 2,646 Pinili 683 Santa Filomena 1,053 Santo Tomas 884 Siguiran 1,258 Simayung 1,321 Sirit 792 San Agustin 771 San Julian 627 Santa -

Teaming up for Safe Motherhood

Maternal and Child Health Project TEAMING UP for Safe Motherhood The Biliran and Ifugao Experience TEAMING UP for Safe Motherhood: The Biliran and Ifugao Experience This book is a publication of the Department of Health, and all rights are thus reserved by the DOH. This publication, however, may be freely reviewed, abstracted, reproduced and translated, in part or in its entirety, as long as it is not for sale or used in conjunction with commercial purposes. The DOH would appreciate that it be acknowledged in the reproduced or translated version and receive a copy of such version. Copyright 2008 Department of Health San Lazaro Compound, Sta. Cruz, Manila (0632) 743-83-01 to 23 http://www.doh.gov.ph All Rights Reserved Editorial and Design Consultant: Gerard Jerome C. Dumlao With technical and financial support of JICA/MCH Project TEAMING UP for Safe Motherhood The Biliran and Ifugao experience Maternal and Child Health Project Acronyms AMADHS Aguinaldo -Mayoyao- Alfonso Lista District Health System BEmONC Basic Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care BHS Barangay Health Station BHW Barangay Health Worker BNS Barangay Nutrition Scholar BPH Biliran Provincial Hospital CEmONC Comprehensive Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care CMMNC Community Managed Maternal and Newborn Care CHD Center for Health Development DH District Hospital DOH Department of Health EmONC Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care LSS Life Saving Skills MCH Maternal and Child Health MCP Maternal Care Package MHO Municipal Health Office MDR Maternal Death Review MMR Maternal Mortality Ratio NCDPC National Center for Disease Prevention and Control NMR Neonatal Mortality Rate PhilHealth Philippine Health Insurance Corporation PHO Rural Health Midwife RHM Rural Health Unit RHU Skilled Birth Attendant SBA Traditional Birth Attendant TBA Technical Working Group TWG Table of Contents Foreword By Hon. -

(CSHP) DOLE-Cordillera Administrative Region August 2017

REGIONAL REPORT ON THE APPROVED CONSTRUCTION SAFETY & HEALTH PROGRAM (CSHP) DOLE-Cordillera Administrative Region August 2017 No. Company Name and Address Project Name Project Owner Date Approved C.R. DOMINGO 142 National CONSTRUCTION AND 1 Highway, Brgy. 3, 17PG0011- Construction of Ibulao Flood Control DPWH-IFDEO August 1, 2017 POWER DEVELOPMENT, San Mateo , Isabela INC. 16PG0068- Construction/Upgrading/Rehabilitation/of C.R. DOMINGO 142 National Drainage along Nueva Vizcaya-Ifugao-Mt. Province CONSTRUCTION AND 2 Highway, Brgy. 3, Boundary Road, K0301+509,K0295+700- DPWH-IFDEO August 1, 2017 POWER DEVELOPMENT, San Mateo , Isabela K0295+800,K0301+100-K0301+400,K0312+600- INC. K0313+107,K0314+060-K0314+198 17PJ0018- Local Infrastructure Program- Construction of ROJUNED 3 Ramon, Isabela Rural Health Unit (Extension), Barangay Santa Maria, DPWH-ISDEO August 1, 2017 CONSTRUCTION Alfonso Lista, Ifugao C.R. DOMINGO 142 National CONSTRUCTION AND 17PG0012- Construction of Banao Flood Control 4 Highway, Brgy. 3, DPWH-IFDEO August 1, 2017 POWER DEVELOPMENT, (Tungngod Side) San Mateo , Isabela INC. C.R. DOMINGO CONSTRUCTION AND POWER DEVELOPMENT, 142 National CW-ALPIP-01-2017/Construction of Transbasin Tunnel 5 INC. AND Highway, Brgy. 3, and its Appurtenant Structures of Alfonso Lista Pump NIA-CAR August 1, 2017 CONSOLIDATED San Mateo , Isabela Irrigation Project (ALPIP) EXPLOSIVES GROUP CORPORATION (JV) 17PK0042- Rehabilitation Restoration of National Road BLESSING BUILDERS & Purok 4, Bulanao, along Various Section od Upper Kalinga Roads Mt. 6 -

Countering a Colonial Fantasy of Filipinos Highlanders

COUNTERING A COLONIAL FANTASY OF FILIPINOS HIGHLANDERS: ETHNIC VERSUS ETHICAL TOURISM By Isadora Sharon A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Humboldt State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Applied Anthropology Committee Membership Dr. Mary Scoggin, Committee Chair Dr. Llyn Smith, Committee Member Dr. Fred Krissman, Committee Member Ms. Rebecca Robertson, Program Graduate Coordinator July 2017 ABSTRACT COUNTERING A COLONIAL FANTASY OF FILIPINOS HIGHLANDERS: ETHNIC VERSUS ETHICAL TOURISM Isadora Sharon This thesis is based on work undertaken in the province of Ifugao located in the northern region of the Philippines islands. I examined how community members in Kiangan Ifugao utilize tourism to revive and preserve their traditions and protest against the ethnic tourism industry in Banaue Ifugao. I also investigated the false representations of indigenous people in the ethnic tourism industry. This research consists of interviews, focus groups and the analysis of over 40 ethnic tourism ads. Social movements of grassroots organizations among indigenous populations of various regions of the world may attempt to counter legacies of colonial racism and continuing culture exploitation, which are significant aspects of the contemporary ethnic tourism industry. The goal of this thesis is to raise consciousness about the colonial legacy of ethnic tourism and how it tends to frame indigenous people into romantic historical stereotypes. The era of enslavement and oppression is being carried forward into an era of commercial exploitation by some in the tourism industry. By raising the consciousness of those who travel, this author hopes to encourage tourists to seek ethical methods to learn about other cultures in ways that are respectful and empowering. -

LIST of MUNICIPAL HEALTH OFFICERS Cordillera Administrative Region As of January 7, 2020

LIST OF MUNICIPAL HEALTH OFFICERS Cordillera Administrative Region As of January 7, 2020 Province/ City Provincial Offices and Municipality Rural Health Units Contact Number Email Address Dr. Maria Christina V. Cabrera (PHO II) 0917-175-952 [email protected] [email protected] / Dr. Alex M. Bayubay (DMO V) [email protected] Bangued MHO: Bangued Dr. Glygoric A. Cortes (MHO) Boliney RHU: 0927-421-2696 Boliney Ms. Princess Mae S. Stimson (PHN) Bucay RHU: 0917-302-6781 Bucay Dr. June G. Aznar (MHO) Bucloc RHU: 0906-572-5201 [email protected] Bucloc Dr. Andrew Chamson M. Bacuso (DTTB) Daguioman RHU: 0927-803-9131 Daguioman Dr. Rellin Gay A. Apelo (DTTB) Danglas RHU: 0905-498-0789 [email protected] Danglas ABRA Dr. Joan Rose G. Lampac (MHO) Dolores RHU: 0917-779-3925 Dolores Dr. Joan Rose G. Lampac (DTTB) Lacub RHU: 0917-801-6914 Lacub Ms. Lea Sharon B. Ibay (PHN) 0916-897-3343 Lagangilang RHU: 0921-668-9667 [email protected] Lagangilang Dr. Ruby Rose L. Orosco (MHO) Lagayan RHU: 0917-895-6744/ 0917-412-4627 [email protected] Lagayan Dr. Melanie Aggudong (DTTB) Langiden RHU: Langiden Dr. Antonio L. Valera (PHO I) La Paz RHU: La Paz Ms. Caroline Afos Parel (OIC- PHN) Licuaan- Licuan_Baay RHU: 0926-916-5646 Baay Dr. Ma. Flavie D. Blanca (MHO) Luba RHU: 0917-825-7359 [email protected] Luba Dr. Anthea Marie R. Gabaoen (MHO) Malibcong RHU: 0917-854-4304/ 0977-177-8740 [email protected] Malibcong Dr. Mira Peace B. Kapuno (MHO) Manabo RHU: Manabo Dr. Joel Beleno (MHO) Peñarrubia RHU: 0906-574-1318 [email protected] Peñarrubia Dr. -

This Project Explores Transformations of Locality in the Current Era Of

Practices of place-making – globalisation and locality in the Philippines 1 Practices of place-making – globalisation and locality in the Philippines Abstract: Global flows of people and information in the Asia-Pacific region are creating new forms of place that stretch across national boundaries and rural-urban distinctions. These new mobile forms of place link long-inhabited rural areas to cities, national centres, and to rural frontiers within the nation. Here, we describe new forms of place that are being produced by contemporary migration and economic change, using data from the Philippines and applying Appadurai’s (1995) theorization of translocality. Our analysis links these flows of overseas migrants to concomitant processes of economic change, migration and new rural livelihoods. We outline changing practices of place within the Philippines, exploring ways that transnational migration can articulate with apparently ‘local’ development and the flow-on effects from migration on the spatial patterns of rural livelihoods. Keywords: migration, development, Philippines, livelihoods, place, translocality 2 This paper is about place-making – the ways that people create a sense of place for themselves from networks of exchange, webs of affection and material landscapes. Our thesis is that migration and economic change, key features of globalisation, are producing new forms of local place, forms that sometimes extend across long distances and disparate topographies. To argue this case, we draw on data from community-based studies in the Philippines – the nation with the largest flows of overseas migrant workers in the global economy (Tyner and Donaldson, 1999:1). Our analysis links flows of Filipino migrants to work overseas with concomitant processes of economic change and migration within the Philippine nation. -

GIS with the Ifugaos 91

3/$7)2506 $1' 7(55$&(6 %ULGJLQJ SDUWLFLSDWLRQ DQG *,6 LQ MRLQWOHDUQLQJ IRU ZDWHUVKHG PDQDJHPHQW ZLWK WKH ,IXJDRV RI WKH 3KLOLSSLQHV 3URPRWRUHV 3URI GU LU 1LHOV * 5|OLQJ 3URIHVVRU LQ NQRZOHGJH V\VWHPV LQ GHYHORSLQJ FRXQWULHV :DJHQLQJHQ 8QLYHUVLW\ 7KH 1HWKHUODQGV 3URI GU LU .ODDV -DQ %HHN 3URIHVVRU LQ ODQG HYDOXDWLRQ ,QWHUQDWLRQDO ,QVWLWXWH IRU $HURVSDFH 6XUYH\ DQG (DUWK 6FLHQFHV (QVFKHGH 7KH 1HWKHUODQGV &RSURPRWRU GU 0LFKDHO . 0F&DOO $VVRFLDWH SURIHVVRU ,QWHUQDWLRQDO ,QVWLWXWH IRU $HURVSDFH 6XUYH\ DQG (DUWK 6FLHQFHV (QVFKHGH 7KH 1HWKHUODQGV 3/$7)2506$1'7(55$&(6 %ULGJLQJ SDUWLFLSDWLRQ DQG *,6 LQ MRLQWOHDUQLQJ IRU ZDWHUVKHG PDQDJHPHQW ZLWK WKH ,IXJDRV RI WKH 3KLOLSSLQHV 5KRGRUD 0 *RQ]DOH] 7KHVLV WR IXOILOO WKH UHTXLUHPHQWV IRU WKH GHJUHH RI GRFWRU RQ WKH DXWKRULW\ RI WKH UHFWRU PDJQLILFXV RI :DJHQLQJHQ 8QLYHUVLW\ SURI GU & 0 .DUVVHQ WR EH SXEOLFO\ GHIHQGHG RQ :HGQHVGD\ -XQH IRXU R¶FORFN LQ WKH DIWHUQRRQ DW WKH ,7& $XGLWRULXP ,7& 'LVVHUWDWLRQ 1R 'LVVHUWDWLRQV SUHVHQWHG LQ WKLV VHULHV DUH FRQGXFWHG DW WKH ,QWHUQDWLRQDO ,QVWLWXWH IRU $HURVSDFH 6XUYH\ DQG (DUWK 6FLHQFHV ,7& +HQJHORVHVWUDDW 32 %R[ $$ (QVFKHGH 7KH 1HWKHUODQGV &,3 ± '$7$ .21,1./,-.( %,%/,27+((. 'HQ +DDJ 7KH 1HWKHUODQGV 5KRGRUD 0 *RQ]DOH] ,6%1 3ODWIRUPV DQG 7HUUDFHV %ULGJLQJSDUWLFLSDWLRQ DQG *,6 LQ MRLQWOHDUQLQJIRU ZDWHUVKHG PDQDJHPHQW ZLWK WKH ,IXJDRV RI WKH 3KLOLSSLQHV 5KRGRUD 0 *RQ]DOH] 7KHVLV :DJHQLQJHQ 8QLYHUVLW\ ± :LWK UHIHUHQFHV ± :LWK VXPPDU\ LQ 'XWFK ,6%1 6XEMHFW KHDGLQJV SDUWLFLSDWRU\ *,6 VRFLDO FRQVWUXFWLRQ RI *,6 MRLQWOHDUQLQJ QDWXUDO UHVRXUFH PDQDJHPHQW ZDWHUVKHG PDQDJHPHQW WHUUDFHG DJULFXOWXUH LQGLJHQRXV NQRZOHGJH &RYHU %DWDG ULFH WHUUDFHV %DQDXH ,IXJDR 3KLOLSSLQHV 3KRWRJUDSKHG E\ 7HW 1DS 0DQXHO To the Ifugaos, whose age-old rice terraces demonstrate to the world that simple, but joint, concerted action creates a beautiful and complex harmony of life in a fragile environment. -

Ifugao-Vital-Stat-1St Quarter 2021.Pdf

Republic of the Philippines PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY REGISTERED VITAL EVENTS IN IFUGAO 1ST Quarter 2021 Date of Release : 21 August 2021 Reference No. : SR-2021-16 This report summarizes the data gathered from January to March 2021 documents submitted from the local civil registry offices of the eleven municipalities in the province of Ifugao. The number of vital events in Ifugao for the 1st quarter reached 1, 305 registered documents. This represents 10.88 % increase from the 1,177 registered vital events from the previous quarter. The province generated the following statistics: 801 for birth, 280 for marriage and 224 for death. In this January to March 2021 issue, the Philippine Statistics Authority of Ifugao presents the number of births, marriages, and deaths registered by municipalities in the province. The data are preliminary result from the Decentralized Vital Statistics System 2011 based on the documents submitted by the Local Civil Registry Offices in Ifugao. EXPLANATORY NOTES VITAL STATISTICS are derived from the information obtained at the time when the occurrences of vital events and their characteristics are inscribed in civil register. Vital acts and events are the births, deaths, foetal deaths, marriages, and all events such that have something to do with an individual’s entrance and departure from life together with the changes in civil status that may occur to a person during his lifetime. Recording of these events in the civil register is known as vital or civil registration and the resulting documents are called vital records. Data on vital statistics presented in the release were obtained from the documents registered at the Office the City/ Municipal Civil Registrars all throughout the country and forwarded to the Philippine Statistics Authority.