PS Volulme 53Number4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GIS and Remote Sensing in the Assessment of Magat Watershed in the Philippines

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. The Use GIS and Remote Sensing in the Assessment of Magat Watershed in the Philippines A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Environmental Management Massey University, Turitea Campus, Palmerston North, New Zealand Emerson Tattao 2010 Abstract The Philippine watersheds are continually being degraded— thus threatening the supply of water in the country. The government has recognised the need for effective monitoring and management to avert the declining condition of these watersheds. This study explores the applications of remote sensing and Geographical Information Systems (GIS), in the collection of information and analysis of data, in order to support the development of effective critical watershed management strategies. Remote sensing was used to identify and classify the land cover in the study area. Both supervised and unsupervised methods were employed to establish the most appropriate technique in watershed land cover classification. GIS technology was utilised for the analysis of the land cover data and soil erosion modelling. The watershed boundary was delineated from a digital elevation model, using the hydrological tools in GIS. The watershed classification revealed a high percentage of grassland and increasing agricultural land use, in the study area. The soil erosion modelling showed an extremely high erosion risk in the bare lands and a high erosion risk in the agriculture areas. -

Cagayan Riverine Zone Development Framework Plan 2005—2030

Cagayan Riverine Zone Development Framework Plan 2005—2030 Regional Development Council 02 Tuguegarao City Message The adoption of the Cagayan Riverine Zone Development Framework Plan (CRZDFP) 2005-2030, is a step closer to our desire to harmonize and sustainably maximize the multiple uses of the Cagayan River as identified in the Regional Physical Framework Plan (RPFP) 2005-2030. A greater challenge is the implementation of the document which requires a deeper commitment in the preservation of the integrity of our environment while allowing the development of the River and its environs. The formulation of the document involved the wide participation of concerned agencies and with extensive consultation the local government units and the civil society, prior to its adoption and approval by the Regional Development Council. The inputs and proposals from the consultations have enriched this document as our convergence framework for the sustainable development of the Cagayan Riverine Zone. The document will provide the policy framework to synchronize efforts in addressing issues and problems to accelerate the sustainable development in the Riverine Zone and realize its full development potential. The Plan should also provide the overall direction for programs and projects in the Development Plans of the Provinces, Cities and Municipalities in the region. Let us therefore, purposively use this Plan to guide the utilization and management of water and land resources along the Cagayan River. I appreciate the importance of crafting a good plan and give higher degree of credence to ensuring its successful implementation. This is the greatest challenge for the Local Government Units and to other stakeholders of the Cagayan River’s development. -

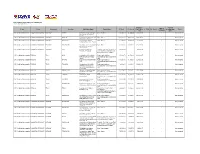

List of KALAHI-CIDSS Subprojects - MAKILAHOK As of February 01, 2019

List of KALAHI-CIDSS Subprojects - MAKILAHOK as of February 01, 2019 Estimated Physical Date of Region Province Municipality Barangay Sub-Project Name Project Type KC Grant LCC Amount Total Project No. Of HHsDate Started Accomplishme Status Completion Cost nt (%) CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA ANABEL Construction of One Unit One School Building 1,181,886.33 347,000.00 1,528,886.33 / / Not yet started Storey Elementary School Building CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA BEKIGAN Construction of Sumang-Paitan Water System 1,061,424.62 300,044.00 1,361,468.62 / / Not yet started Village Water System CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA BELWANG Construction of Pikchat- Water System 471,920.92 353,000.00 824,920.92 / / Not yet started Pattiging Village Water System CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA SACASACAN Rehabilitation of Penged Maballi- Water System 312,366.54 845,480.31 1,157,846.85 / / Not yet started Sacasshak Village Water Supply System CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA SACLIT Improvement of Wetig- Footpath / Foot Trail / Access Trail 931,951.59 931,951.59 / / Not yet started Takchangan Footpath (may include box culvert/drainage as a component for Footpath) CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]IFUGAO TINOC AHIN Construction of 5m x 1000m Road (may include box 251,432.73 981,708.84 1,233,141.57 / / Not yet started FMR Along Telep-Awa-Buo culvert/drainage as a component for Section road) -

Oryza Sativa) Cultivation in the Ifugao Rice Terraces, Philippine Cordilleras

Plant Microfossil Results from Old Kiyyangan Village: Looking for the Introduction and Expansion of Wet-field Rice (Oryza sativa) Cultivation in the Ifugao Rice Terraces, Philippine Cordilleras Mark HORROCKS, Stephen ACABADO, and John PETERSON ABSTRACT Pollen, phytolith, and starch analyses were carried out on 12 samples from two trenches in Old Kiyyangan Village, Ifugao Province, providing evidence for human activity from ca. 810–750 cal. B.P. Seed phytoliths and endosperm starch of cf. rice (Oryza sativa), coincident with aquatic Potamogeton pollen and sponge spicule remains, provide preliminary evidence for wet-field cultivation of rice at the site. The first rice remains appear ca. 675 cal. B.P. in terrace sediments. There is a marked increase in these remains after ca. 530–470 cal. B.P., supporting previous studies suggesting late expansion of the cultivation of wet-field rice in this area. The study represents initial, sediment-derived, ancient starch evidence for O. sativa, and initial, sediment-derived, ancient phytolith evidence for this species in the Philippines. KEYWORDS: Philippines, Ifugao Rice Terraces, rice (Oryza sativa), pollen, phytoliths, starch. INTRODUCTION THE IFUGAO RICE TERRACES IN THE CENTRAL CORDILLERAS,LUZON, were inscribed in the UNESCOWorldHeritage List in 1995, the first ever property to be included in the cultural landscape category of the list (Fig. 1). The nomination and subsequent listing included discussion on the age of the terraces. The terraces were constructed on steep terrains as high as 2000 m above sea level, covering extensive areas. The extensive distribution of the terraces and estimates of the length of time required to build these massive landscape modifications led some researchers to propose a long history of up to 2000–3000 years, which was supported by early archaeological 14C evidence (Barton 1919; Beyer 1955; Maher 1973, 1984). -

Hydraulics Research Wallingford

~ Hydraulics Research Wallingford SEDIMENTATION IN RESERVOIRS: MAGAT RESERVOIR, CAGAYAN VALLEY, LUZON PHILIPPINES 1984 reservoir survey and data analysis R Wooldridge - T Eng (CEI) In collaboration with: National Irrigation Administration, Manila, Philippines Report No OD 69 April 1986 Registered Office: Hydraulics Research Limited, Wallingford, Oxfordshire OXIO 8BA. Telephone: 0491 35381. Telex: 848552 ABSTRACT The Overseas Development Unit of Hydraulics Research Limited is involved in studies to quantify the effects of catchment management in reducing the quantity of sediment being delivered to rivers and deposited in reservoirs. Many recent reservoir studies have shown that observed sedimentation rates can be more than four times the rates estimated during the feasibility studies. This study uses a computer program, developed for a series of Kenyan reservoirs, to calculate the change in storage capacity of Magat Reservoir in north-central Luzon, the Philippines, as the first stage in a unified study of the total catchment erosion/reservoir sedimentstion system. A more detailed examination of the pre-impoundment survey data has shown that the reservoir storage capacity is some 25% greater than the original Feasibility Study and a first estimate of the catchment erosion rate is double the Feasibility Report estimate. CONTENTS Page 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 STUDY LOCATION 1 3 1978 BASE DATA 2 4 HYDROGRAPHIC SURVEY TECHNIQUES 3 S CONTOUR SLICING TECHNIQUE S 6 FIELD DATA ANALYSIS 8 7 MAGAT RESERVOIR VOLUME 10 8 CATCHMENT SEDIMENT YIELD 14 9 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS 15 10 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 16 11 REFERENCES 18 TABLES 1. Designed and observed reservoir siltation rates FIGURES 1- Map of the Philippines 2. Map of Luzon 3. -

DENR-BMB Atlas of Luzon Wetlands 17Sept14.Indd

Philippine Copyright © 2014 Biodiversity Management Bureau Department of Environment and Natural Resources This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the Copyright holder provided acknowledgement of the source is made. BMB - DENR Ninoy Aquino Parks and Wildlife Center Compound Quezon Avenue, Diliman, Quezon City Philippines 1101 Telefax (+632) 925-8950 [email protected] http://www.bmb.gov.ph ISBN 978-621-95016-2-0 Printed and bound in the Philippines First Printing: September 2014 Project Heads : Marlynn M. Mendoza and Joy M. Navarro GIS Mapping : Rej Winlove M. Bungabong Project Assistant : Patricia May Labitoria Design and Layout : Jerome Bonto Project Support : Ramsar Regional Center-East Asia Inland wetlands boundaries and their geographic locations are subject to actual ground verification and survey/ delineation. Administrative/political boundaries are approximate. If there are other wetland areas you know and are not reflected in this Atlas, please feel free to contact us. Recommended citation: Biodiversity Management Bureau-Department of Environment and Natural Resources. 2014. Atlas of Inland Wetlands in Mainland Luzon, Philippines. Quezon City. Published by: Biodiversity Management Bureau - Department of Environment and Natural Resources Candaba Swamp, Candaba, Pampanga Guiaya Argean Rej Winlove M. Bungabong M. Winlove Rej Dumacaa River, Tayabas, Quezon Jerome P. Bonto P. Jerome Laguna Lake, Laguna Zoisane Geam G. Lumbres G. Geam Zoisane -

Climate-Responsive Integrated Master Plan for Cagayan River Basin

Climate-Responsive Integrated Master Plan for Cagayan River Basin VOLUME I - EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Submitted by College of Forestry and Natural Resources University of the Philippines Los Baños Funded by River Basin Control Office Department of Environment and Natural Resources CLIMATE-RESPONSIVE INTEGRATED RIVER BASIN MASTER PLAN FOR THE i CAGAYAN RIVER BASIN Table of Contents 1 Rationale .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 2 Objectives of the Study .............................................................................................................................. 1 3 Scope .................................................................................................................................................................. 1 4 Methodology .................................................................................................................................................. 2 5 Assessment Reports ................................................................................................................................... 3 5.1 Geophysical Profile ........................................................................................................................... 3 5.2 Bioecological Profile ......................................................................................................................... 6 5.3 Demographic Characteristics ...................................................................................................... -

Flood Risk Assessment of Major River Basins in the Philippines

International Journal of GEOMATE, Dec., 2019 Vol.17, Issue 64, pp. 201- 208 ISSN: 2186-2982 (P), 2186-2990 (O), Japan, DOI: https://doi.org/10.21660/2019.64.17155 Geotechnique, Construction Materials and Environment FLOOD RISK ASSESSMENT OF MAJOR RIVER BASINS IN THE PHILIPPINES Christian Dominick Q. Alfonso1, Marloe B. Sundo*2, Richelle G. Zafra2, Perlie P. Velasco2, Jedidiah Joel C. Aguirre2 and Marish S. Madlangbayan2 1University of the Philippines Los Baños Foundation, Inc., Philippines; 2University of the Philippines Los Baños, Philippines *Corresponding Author, Received: 00 Oct. 2019, Revised: 00 Nov. 2019, Accepted: 00 Dec. 2019 ABSTRACT: Disaster risk management is vital in strengthening the resilience to and reduction of losses brought by natural disasters. In Philippines where typhoons frequently occur, flood risk maps are essential for the protection of communities and ecosystems in watersheds. This study created flood inundation maps with climate change considerations under 2020 A1B1 and 2050 A1B1 scenarios for four major river basins in the Philippines: the Agno, Cagayan, Mindanao, and Buayan-Malungon River Basins. From these maps, the most vulnerable areas for each basin are identified using GIS mapping software. Sixteen inundation risk maps were generated, four for each river basin, in terms of built-up areas, roads, bridges, and dams. Results showed that the northern part of Cagayan River Basin and the central parts of the Agno and Mindanao River Basins are the most flood-prone areas, while the Buayan-Malungon River Basin will have no significant inundation problems. Suitable adaptation and mitigation options were provided for each river basin. Keywords: Disaster risk reduction, Climate change adaption, Inundation, Risk Mapping 1. -

JOSELINE “JOYCE” P. NIWANE Assistant Secretary for Policy and Plans DSWD-Central Office Batasan Pambansa Complex, Constitution Hills Quezon City

JOSELINE “JOYCE” P. NIWANE Assistant Secretary for Policy and Plans DSWD-Central Office Batasan Pambansa Complex, Constitution Hills Quezon City Personal Information Date of Birth: April 3, 1964 Place of Birth: Baguio City Marital Status: Single Parents: COL. Francisco Niwane(Ret) Mrs. Adela P. Niwane Education Elementary: Holy Family Academy, Baguio City 1971-1977 High School: Holy Family Academy, Baguio City 1977-1981 College: Saint Louis University, Baguio City 1982-1985 Post Education: 1. University of the Philippines (1989-1990) - Masters in Public Administration 2. University of Washington, Seattle, USA ( 2001-2002) -Post Graduate in Public Policy and Social Justice 3. Saint Mary’s University (2005-2006) - Masters in Public Administration AWARDS/ FELLOWSHIPS RECEVEIVED: 1986 : “Merit of Valor” Award – World Vision International 1996 : 1st Provincial AWARD OF MERIT – Provincial Government of Ifugao 1997 : Dangal ng Bayan Awardee - CSC and Pres. Fidel V. Ramos 1998 : Model Public Servant Awardee of the Year – KILOSBAYAN AND GMA 7 1998 : Outstanding Cordillera Woman of the Year – Midland Courier 1998 : 1st National Congress of Honor Awardee 2001 : Ifugao Achievers Award - Provincial Government of Ifugao 2001-2002 : Hubert Humphrey Fellowship Program/Fulbright- United States of America Government 2013 : Best Provincial Social Welfare and Dev’t. Officer – DSWD-CAR 2015 : Galing Pook Award - DILG 2016 : Gawad Gabay : Galing sa Paggabay sa mga Bata para sa Magandang Buhay “ Champion of Positive and Non-violent discipline for the Filipino -

Pdf | 308.16 Kb

2. Damaged Infrastructure and Agriculture (Tab D) Total Estimated Cost of Damages PhP 411,239,802 Infrastructure PhP 29,213,821.00 Roads & Bridges 24,800,000.00 Transmission Lines 4,413,821.00 Agriculture 382,025,981.00 Crops 61,403,111.00 HVCC 5,060,950.00 Fisheries 313,871,920.00 Facilities 1,690,000.00 No report of damage on school buildings and health facilities as of this time. D. Emergency Incidents Monitored 1. Region II a) On or about 10:00 AM, 08 May 2009, one (1) ferry boat owned by Brgy Captain Nicanor Taguba of Gagabutan, Rizal, bound to Cambabangan, Rizal, Cagayan, to attend patronal fiesta with twelve (12) passengers on board, capsized while crossing the Matalad River. Nine (9) passengers survived while three (3) are still missing identified as Carmen Acasio Anguluan (48 yrs /old), Vladimir Acasio Anguluan (7 yrs /old) and Mac Dave Talay Calibuso (5 yrs/old), all from Gagabutan East Rizal, Cagayan. The 501st Infantry Division (ID) headed by Col. Remegio de Vera, PNP personnel and some volunteers from Rizal, Cagayan conducted search and rescue operations. b) In Nueva Vizcaya, 31 barangays were flooded: Solano (16), Bagabag (5), Bayombong (4), Bambang (4), in Dupax del Norte (1) and in Dupax del Sur (1). c) Barangays San Pedro and Manglad in Maddela, Quirino were isolated due to flooding. e) The low-lying areas of Brgys Mabini and Batal in Santiago City, 2 barangays in Dupax del Norte and 4 barangays in Bambang were rendered underwater with 20 families evacuated at Bgy Mabasa Elementary School. -

Download File

©️ Indigenous Peoples Rights International, 2021. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the publisher's prior written permission. The quotation, reproduction without alteration, and transmission of this document are authorized, provided that it is for non-commercial purposes and with attribution to the copyright holder. Indigenous Peoples Rights International. “Defending Our Lands, Territories and Natural Resources Amid the COVIDt-19 Pandemic: Annual Report on Criminalization of, Violence and Impunity Against Indigenous Peoples.” April 2021. Baguio City, Philippines. Photos Cover Page (Top) Young Lumad women protesting in UP Diliman with placards saying "Women, our place is in the struggle." (Photo: Save Our Schools (SOS) Network) (Bottom) The Nahua People of the ejido of Carrizalillo blocked the entrance to the mines on September 3, 2020 due to Equinox Gold’s breach of the agreement. (Photo: Centro de Derechos Humanos de la Montaña Tlachinollan) Indigenous Peoples Rights International # 7 Planta baja, Calvary St., Easter Hills Subdivision Central Guisad, Baguio City 2600 Filipinas www.iprights.org ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The country contexts and case stories were developed with support from: Diel Mochire, Joseph Itongwa and Aquilas Koko Ngomo (Democratic Republic of Congo); Sonia Guajajara and Carolina Santana (Brazil); Leonor Zalabata, Francisco Vanegas, Maria Elvira Guerra and Héctor Jaime Vinasco (Colombia); Sandra Alarcon, Ariane Assemat, Carmen Herrera and Abel Barrera (Mexico); Gladson Dungdung, Rajendra Tadavi, Siraj Dutta, Sidhart Nayak and Praful Samantaray (India); Prince Albert Turtogo, Tyrone Beyer, Jill Cariño, Marifel Macalanda, and Giya Clemente (Philippines). -

The Feasibility Study of the Flood Control Project for the Lower Cagayan River in the Republic of the Philippines

JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES THE FEASIBILITY STUDY OF THE FLOOD CONTROL PROJECT FOR THE LOWER CAGAYAN RIVER IN THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES FINAL REPORT VOLUME II MAIN REPORT FEBRUARY 2002 NIPPON KOEI CO., LTD. NIKKEN Consultants, Inc. SSS JR 02-07 List of Volumes Volume I : Executive Summary Volume II : Main Report Volume III-1 : Supporting Report Annex I : Socio-economy Annex II : Topography Annex III : Geology Annex IV : Meteo-hydrology Annex V : Environment Annex VI : Flood Control Volume III-2 : Supporting Report Annex VII : Watershed Management Annex VIII : Land Use Annex IX : Cost Estimate Annex X : Project Evaluation Annex XI : Institution Annex XII : Transfer of Technology Volume III-3 : Supporting Report Drawings Volume IV : Data Book The cost estimate is based on the price level and exchange rate of June 2001. The exchange rate is: US$1.00 = PHP50.0 = ¥120.0 PREFACE In response to a request from the Government of the Republic of the Philippines, the Government of Japan decided to conduct the Feasibility Study of the Flood Control Project for the Lower Cagayan River in the Republic of the Philippines and entrusted the study to the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). JICA selected and dispatched a study team headed by Mr. Hideki SATO of NIPPON KOEI Co.,LTD. (consist of NIPPON KOEI Co.,LTD. and NIKKEN Consultants, Inc.) to the Philippines, six times between March 2000 and December 2001. In addition, JICA set up an advisory committee headed by Mr. Hidetomi Oi, Senior Advisor of JICA between March 2000 and February 2002, which examined the study from technical points of view.