Countering a Colonial Fantasy of Filipinos Highlanders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POPCEN Report No. 3.Pdf

CITATION: Philippine Statistics Authority, 2015 Census of Population, Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density ISSN 0117-1453 ISSN 0117-1453 REPORT NO. 3 22001155 CCeennssuuss ooff PPooppuullaattiioonn PPooppuullaattiioonn,, LLaanndd AArreeaa,, aanndd PPooppuullaattiioonn DDeennssiittyy Republic of the Philippines Philippine Statistics Authority Quezon City REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES HIS EXCELLENCY PRESIDENT RODRIGO R. DUTERTE PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY BOARD Honorable Ernesto M. Pernia Chairperson PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY Lisa Grace S. Bersales, Ph.D. National Statistician Josie B. Perez Deputy National Statistician Censuses and Technical Coordination Office Minerva Eloisa P. Esquivias Assistant National Statistician National Censuses Service ISSN 0117-1453 FOREWORD The Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) conducted the 2015 Census of Population (POPCEN 2015) in August 2015 primarily to update the country’s population and its demographic characteristics, such as the size, composition, and geographic distribution. Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density is among the series of publications that present the results of the POPCEN 2015. This publication provides information on the population size, land area, and population density by region, province, highly urbanized city, and city/municipality based on the data from population census conducted by the PSA in the years 2000, 2010, and 2015; and data on land area by city/municipality as of December 2013 that was provided by the Land Management Bureau (LMB) of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). Also presented in this report is the percent change in the population density over the three census years. The population density shows the relationship of the population to the size of land where the population resides. -

Multi-Functionality of the Ifugao Rice Terraces

MULTI-FUNCTIONALITY OF THE IFUGAO RICE TERRACES Rogelio N. Concepcion Project Leader Director, Bureau of Soils and Water Management Multi-functionality of the Ifugao Rice Terraces Phase 1. Country paper for the ASEAN- Japan Multi-Functionality of Paddy Farming and its Impacts in ASEAN Countries Multi-functionality of the Ifugao Rice Terraces Participating Countries Brunei, Cambodia, Lao-PDR, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam, Philippines Duration Phase 1: April 2001 – November 2003 Phase II: December 2003 – March 2006 Funding Source – MAF, Japan Multi-functionality of the Ifugao Rice Terraces Project Phase 1 Objectives 1. To establish common understanding on the importance of multi-functionality through analytical work in ASEAN member countries 2. To create appreciation on the contribution on multi-functionality to the ASEAN countries long term policy making for further development of sustainable agriculture in the rural areas. Operational Framework of Multi-functionality Groentfledt, 2003 Multi-functionality concept was first articulated in the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio De Janeiro in the context of discussion of contribution of agriculture to environmentally Sustainable Development. Matsumoto, 2002 Agricultural activities not only produce tangible products in the form of food and fiber, but also create non-tangible values, which are referred as the multi-functionality of agriculture. Multi-functionality is not tradable and cannot be reflected in the food prices. The tradable or marketable products of farming provide direct -

Inclusion and Cultural Preservation for the Ifugao People

421 Journal of Southeast Asian Human Rights, Vol.2 No. 2 December 2018. pp. 421-447 doi: 10.19184/jseahr.v2i2.8232 © University of Jember & Indonesian Consortium for Human Rights Lecturers Inclusion and Cultural Preservation for the Ifugao People Ellisiah U. Jocson Managing Director, OneLife Foundation Inc. (OLFI), M.A.Ed Candidate, University of the Philippines, Diliman Abstract This study seeks to offer insight into the paradox between two ideologies that are currently being promoted in Philippine society and identify the relationship of both towards the indigenous community of the Ifugao in the country. Inclusion is a growing trend in many areas, such as education, business, and development. However, there is ambiguity in terms of educating and promoting inclusion for indigenous groups, particularly in the Philippines. Mandates to promote cultural preservation also present limits to the ability of indigenous people to partake in the cultures of mainstream society. The Ifugao, together with other indigenous tribes in the Philippines, are at a state of disadvantage due to the discrepancies between the rights that they receive relative to the more urbanized areas of the country. The desire to preserve the Ifugao culture and to become inclusive in delivering equal rights and services create divided vantages that seem to present a rift and dilemma deciding which ideology to promulgate. Apart from these imbalances, the stance of the Ifugao regarding this matter is unclear, particularly if they observe and follow a central principle. Given that the notion of inclusion is to accommodate everyone regardless of “race, gender, disability, ethnicity, social class, and religion,” it is highly imperative to provide clarity to this issue and identify what actions to take. -

The White Apos: American Governors on the Cordillera Central Frank L

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Alumni Book Gallery 1987 The White Apos: American Governors on the Cordillera Central Frank L. Jenista Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/alum_books Part of the Other History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Jenista, Frank L., "The White Apos: American Governors on the Cordillera Central" (1987). Alumni Book Gallery. 334. https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/alum_books/334 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Alumni Book Gallery by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The White Apos: American Governors on the Cordillera Central Disciplines History | Other History | United States History Publisher New Day Publishers Publisher's Note Excerpt provided by kind permission of New Day Publishers. There will be no selling of the book outside of New Day. ISBN 971100318X This book is available at DigitalCommons@Cedarville: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/alum_books/334 ,. • • AMERICAN GOVERNORS ON 1HE CORDILLERA CENTRAL FRANKL. JENISTA New Day- Publishers Quezon City 1987 PREFACE For at least the last five centuries of recorded' history, Southeast Asians have been conspicuously divided into peoples of the hills and of the plains. Hjghlanders have tended to be independent animists living in small communities isolated by war or terrain, ·without developed systems of either kinship or peonage and order ing their lives according to custom and oral tradition. .Their lowland . neighbors, exposed to the greater traditions of Buddhism, Islam or Christianity, lived in more complex worlds with courts and chroni cles, plazas and cathedrals. -

Municipality of La Trinidad BARANGAY LUBAS

Republic of the Philippines Province of Benguet Municipality of La Trinidad BARANGAY LUBAS PHYSICAL AND SOCIO-ECONOMIC PROFILE I. PHYSICAL PROFILE Geographic Location Barangay Lubas is located on the southern part of the municipality of La Trinidad. It is bounded on the north by Barangay Tawang and Shilan, to the south by Barangay Ambiong and Balili, to the east by Barangay Shilan, Beckel and Ambiong and to the west by Barangay Tawang and Balili. With the rest of the municipality of La Trinidad, it lies at 16°46’ north latitude and 120° 59 east longitudes. Cordillera Administrative Region MANKAYAN Apayao BAKUN BUGUIAS KIBUNGAN LA TRINIDAD Abra Kalinga KAPANGAN KABAYAN ATOK TUBLAY Mt. Province BOKOD Ifugao BAGUIO CITY Benguet ITOGON TUBA Philippines Benguet Province 1 Sally Republic of the Philippines Province of Benguet Municipality of La Trinidad BARANGAY LUBAS POLITICAL MAP OF BARANGAY LUBAS Not to Scale 2 Sally Republic of the Philippines Province of Benguet Municipality of La Trinidad BARANGAY LUBAS Barangay Tawang Barangay Shilan Barangay Beckel Barangay Balili Barangay Ambiong Prepared by: MPDO La Trinidad under CBMS project, 2013 Land Area The Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) Cadastral survey reveals that the land area of Lubas is 240.5940 hectares. It is the 5th to the smallest barangays in the municipality occupying three percent (3%) of the total land area of La Trinidad. Political Subdivisions The barangay is composed of six sitios namely Rocky Side 1, Rocky Side 2, Inselbeg, Lubas Proper, Pipingew and Guitley. Guitley is the farthest and the highest part of Lubas, connected with the boundaries of Beckel and Ambiong. -

Directory of Participants 11Th CBMS National Conference

Directory of Participants 11th CBMS National Conference "Transforming Communities through More Responsive National and Local Budgets" 2-4 February 2015 Crowne Plaza Manila Galleria Academe Dr. Tereso Tullao, Jr. Director-DLSU-AKI Dr. Marideth Bravo De La Salle University-AKI Associate Professor University of the Philippines-SURP Tel No: (632) 920-6854 Fax: (632) 920-1637 Ms. Nelca Leila Villarin E-Mail: [email protected] Social Action Minister for Adult Formation and Advocacy De La Salle Zobel School Mr. Gladstone Cuarteros Tel No: (02) 771-3579 LJPC National Coordinator E-Mail: [email protected] De La Salle Philippines Tel No: 7212000 local 608 Fax: 7248411 E-Mail: [email protected] Batangas Ms. Reanrose Dragon Mr. Warren Joseph Dollente CIO National Programs Coordinator De La Salle- Lipa De La Salle Philippines Tel No: 756-5555 loc 317 Fax: 757-3083 Tel No: 7212000 loc. 611 Fax: 7260946 E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] Camarines Sur Brother Jose Mari Jimenez President and Sector Leader Mr. Albino Morino De La Salle Philippines DEPED DISTRICT SUPERVISOR DEPED-Caramoan, Camarines Sur E-Mail: [email protected] Dr. Dina Magnaye Assistant Professor University of the Philippines-SURP Cavite Tel No: (632) 920-6854 Fax: (632) 920-1637 E-Mail: [email protected] Page 1 of 78 Directory of Participants 11th CBMS National Conference "Transforming Communities through More Responsive National and Local Budgets" 2-4 February 2015 Crowne Plaza Manila Galleria Ms. Rosario Pareja Mr. Edward Balinario Faculty De La Salle University-Dasmarinas Tel No: 046-481-1900 Fax: 046-481-1939 E-Mail: [email protected] Mr. -

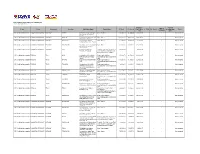

List of KALAHI-CIDSS Subprojects - MAKILAHOK As of February 01, 2019

List of KALAHI-CIDSS Subprojects - MAKILAHOK as of February 01, 2019 Estimated Physical Date of Region Province Municipality Barangay Sub-Project Name Project Type KC Grant LCC Amount Total Project No. Of HHsDate Started Accomplishme Status Completion Cost nt (%) CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA ANABEL Construction of One Unit One School Building 1,181,886.33 347,000.00 1,528,886.33 / / Not yet started Storey Elementary School Building CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA BEKIGAN Construction of Sumang-Paitan Water System 1,061,424.62 300,044.00 1,361,468.62 / / Not yet started Village Water System CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA BELWANG Construction of Pikchat- Water System 471,920.92 353,000.00 824,920.92 / / Not yet started Pattiging Village Water System CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA SACASACAN Rehabilitation of Penged Maballi- Water System 312,366.54 845,480.31 1,157,846.85 / / Not yet started Sacasshak Village Water Supply System CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA SACLIT Improvement of Wetig- Footpath / Foot Trail / Access Trail 931,951.59 931,951.59 / / Not yet started Takchangan Footpath (may include box culvert/drainage as a component for Footpath) CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]IFUGAO TINOC AHIN Construction of 5m x 1000m Road (may include box 251,432.73 981,708.84 1,233,141.57 / / Not yet started FMR Along Telep-Awa-Buo culvert/drainage as a component for Section road) -

Oryza Sativa) Cultivation in the Ifugao Rice Terraces, Philippine Cordilleras

Plant Microfossil Results from Old Kiyyangan Village: Looking for the Introduction and Expansion of Wet-field Rice (Oryza sativa) Cultivation in the Ifugao Rice Terraces, Philippine Cordilleras Mark HORROCKS, Stephen ACABADO, and John PETERSON ABSTRACT Pollen, phytolith, and starch analyses were carried out on 12 samples from two trenches in Old Kiyyangan Village, Ifugao Province, providing evidence for human activity from ca. 810–750 cal. B.P. Seed phytoliths and endosperm starch of cf. rice (Oryza sativa), coincident with aquatic Potamogeton pollen and sponge spicule remains, provide preliminary evidence for wet-field cultivation of rice at the site. The first rice remains appear ca. 675 cal. B.P. in terrace sediments. There is a marked increase in these remains after ca. 530–470 cal. B.P., supporting previous studies suggesting late expansion of the cultivation of wet-field rice in this area. The study represents initial, sediment-derived, ancient starch evidence for O. sativa, and initial, sediment-derived, ancient phytolith evidence for this species in the Philippines. KEYWORDS: Philippines, Ifugao Rice Terraces, rice (Oryza sativa), pollen, phytoliths, starch. INTRODUCTION THE IFUGAO RICE TERRACES IN THE CENTRAL CORDILLERAS,LUZON, were inscribed in the UNESCOWorldHeritage List in 1995, the first ever property to be included in the cultural landscape category of the list (Fig. 1). The nomination and subsequent listing included discussion on the age of the terraces. The terraces were constructed on steep terrains as high as 2000 m above sea level, covering extensive areas. The extensive distribution of the terraces and estimates of the length of time required to build these massive landscape modifications led some researchers to propose a long history of up to 2000–3000 years, which was supported by early archaeological 14C evidence (Barton 1919; Beyer 1955; Maher 1973, 1984). -

2278-6236 the Migrants of Kalinga

International Journal of Advanced Research in ISSN: 2278-6236 Management and Social Sciences Impact Factor: 6.284 THE MIGRANTS OF KALINGA: FOCUS ON THEIR LIFE AND EXPERIENCES Janette P. Calimag, Kalinga-Apayao State College, Bulanao Tabuk City, Kalinga Abstract: This study is a descriptive-historical research on the life and experiences of migrants in Kalinga. This was conducted to understand the life migrants and the challenges they faced as they transferred residence. The participants of the study are the migrants of Kalinga aged 55 and above. Interview was the primary method used in gathering data for the study. An interview guide was used as a basis for questioning while note-taking was done by the researcher to document the information supplied by the participants. All conversations were also recorded through a tape recorder. Secondary resources such as researches, books and articles were used to further explain the results of the study. Results of the study revealed that the life of migrants is not just as easy, they faced a lot of challenges after migrating. They experienced financial difficulties, problems in relation to bodong, fear of Kalingas due to political conflicts, land grabbing, health problems, tribal wars, and differences in beliefs and religion. In view of the aforementioned findings and conclusions, the following topics are hereby recommended that this research will be a basis of the government of Kalinga as they create programs that involve migrants and as they review the implementation of bodong in their locale. Keywords: Migrants, focus, life, experiences, Kalinga INTRODUCTION One of the most difficult decisions a person can make is to leave the place where he used to live and transfer to a new community with more opportunities than the former. -

The Philippines Northern Highlights & Bohol Beach Stay 14 Days / 13 Nights

THE PHILIPPINES NORTHERN HIGHLIGHTS & BOHOL BEACH STAY 14 DAYS / 13 NIGHTS 14 DAYS 13 NIGHTS MANILA - NORTHERN ROUNDTRIP - BOHOL 2019-2020 Ever wonder where this masterpiece of nature is? This is Banaue, located on the mountains of the Philippine Cordillera, a place in the north of the Philippines famous for its rice terraces. Yes the Philippines consist of thousands of islands but you can also find mountains and elevated landscapes. After discovering the local villages, the natural wonders, and the hanging coffins of Sagada, a relaxing beach stay to end your stay makes for a perfect holiday! www.bluehorizons.travel Page 1 of 6 ITINERARY DAY 1 MANILA Arrive in Manila. You will be met and transferred to your hotel. Check in and overnight. Accommodation: 2 nights in Manila DAY 2 MANILA Meet our Tour Representative at the lobby of your hotel for your Exploring Old Manila Tour. The city of Manila is bisected by Pasig River, a tidal estuary that connects Manila Bay and Laguna de Bay. On its southern banks is the city center, where government and private offices, schools, shopping malls and manmade historical landmarks are located; on its northern edge are the densely populated, working class districts such as Quiapo, Binondo and Escolta, which used to be the city’s commercial district during the Spanish colonial period. Traversing from south to north, the tour affords one a glimpse of Manila’s colonial past and its relevance in the present times. ‘Exploring Old Manila’ combines a visit to the main attractions of Intramuros, including Rizal Park. A ‘calesa’ ride (horse- drawn carriage) will take you to Chinatown in Binondo. -

JOSELINE “JOYCE” P. NIWANE Assistant Secretary for Policy and Plans DSWD-Central Office Batasan Pambansa Complex, Constitution Hills Quezon City

JOSELINE “JOYCE” P. NIWANE Assistant Secretary for Policy and Plans DSWD-Central Office Batasan Pambansa Complex, Constitution Hills Quezon City Personal Information Date of Birth: April 3, 1964 Place of Birth: Baguio City Marital Status: Single Parents: COL. Francisco Niwane(Ret) Mrs. Adela P. Niwane Education Elementary: Holy Family Academy, Baguio City 1971-1977 High School: Holy Family Academy, Baguio City 1977-1981 College: Saint Louis University, Baguio City 1982-1985 Post Education: 1. University of the Philippines (1989-1990) - Masters in Public Administration 2. University of Washington, Seattle, USA ( 2001-2002) -Post Graduate in Public Policy and Social Justice 3. Saint Mary’s University (2005-2006) - Masters in Public Administration AWARDS/ FELLOWSHIPS RECEVEIVED: 1986 : “Merit of Valor” Award – World Vision International 1996 : 1st Provincial AWARD OF MERIT – Provincial Government of Ifugao 1997 : Dangal ng Bayan Awardee - CSC and Pres. Fidel V. Ramos 1998 : Model Public Servant Awardee of the Year – KILOSBAYAN AND GMA 7 1998 : Outstanding Cordillera Woman of the Year – Midland Courier 1998 : 1st National Congress of Honor Awardee 2001 : Ifugao Achievers Award - Provincial Government of Ifugao 2001-2002 : Hubert Humphrey Fellowship Program/Fulbright- United States of America Government 2013 : Best Provincial Social Welfare and Dev’t. Officer – DSWD-CAR 2015 : Galing Pook Award - DILG 2016 : Gawad Gabay : Galing sa Paggabay sa mga Bata para sa Magandang Buhay “ Champion of Positive and Non-violent discipline for the Filipino -

I Stella M. Gran-O'donn

Being, Belonging, and Connecting: Filipino Youths’ Narratives of Place(s) and Wellbeing in Hawai′i Stella M. Gran-O’Donnell A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2016 Reading Committee: Karina L. Walters, Chair Tessa A. Evans Campbell Lynne C. Manzo Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Social Work © Copyright 2016 Stella M. Gran-O’Donnell University of Washington Abstract Being, Belonging, and Connecting: Filipino Youths’ Narratives of Place(s) and Wellbeing in Hawai′i Stella M. Gran-O’Donnell Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Karina L. Walters School of Social Work Background: Environmental climate change is an urgent concern for Pacific Islanders with significant impact on place along with bio-psycho-social-cultural-spiritual influences likely to affect communities’ wellbeing. Future generations will bear the burden. Indigenous scholars have begun to address climate-based place changes; however, immigrant Pacific Islander populations have been ignored. Although Filipinos are one of the fastest growing U.S. populations, the second largest immigrant group, and second largest ethnic group in Hawai’i, lack of understanding regarding their physical health and mental wellbeing remains, especially among youth. This dissertation addresses these gaps. In response to Kemp’s (2011) and Jack’s (2010, 2015) impassioned calls for the social work profession to advance place research among vulnerable populations, this qualitative study examined Filipino youths’ (15-23) experiences of place(s) and geographic environment(s) in Hawai′i. Drawing on Indigenous worldviews, this study examined how youth narrate their sense of place, place attachments, ethnic/cultural identity/ies, belonging, connectedness to ancestral (Philippines) and contemporary homelands (Hawai’i), virtual environment(s), and how these places connect to wellbeing.