This Project Explores Transformations of Locality in the Current Era Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Province of Nueva Vizcaya Municipality of Aritao

SUBASTA 2019 RURAL BANK OF BAYOMBONG, INC. BAYOMBONG, NUEVA VIZCAYA TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN: Notice is hereby given that pursuant to the Revised Rules and Regulations governing the rural banks, as amended, particularly the last paragraph of Section 22 of the said rules regarding disposition of all assets acquired in settlement of loans, the Rural Bank of Bayombong, Inc., hereby announces that on May 15, 2019, June 19, 2019, July 17, 2019, August 22, 2019, September 18, 2019, October 16, 2019, November 20, 2019, December 18, 2019 between the hours of 8:30 in the morning and 3:00 in the afternoon in the premises of main building of the said Rural Bank of Bayombong, Inc. the following assets acquired will be sold for cash to the highest bidder by way of public auction sale to be conducted by the President/Gen. Manager, Mrs. Martha R. Ramos. All properties not sold during the first date of auction sale aforementioned shall be offered again at subsequent dates until properties shall have been disposed. PROVINCE OF NUEVA VIZCAYA MUNICIPALITY OF ARITAO LOCATION OF PROPERTY STARTING BID T-128359- 796 sq. m.- Residential Lot 645,135.84 Pariir, Comon, Aritao, Nueva Vizcaya T-132217- 925 sq. m.- Residential Lot/Orchard 751,813.16 Pariir, Comon, Aritao, Nueva Vizcaya T-142181- 761 sq. m.- Residential Lot 342,320.27 Pk. Namnama, Bone North, Aritao, NV. T-142521-33,667 sq. m.- Veg. Land 273,049.38 Canabuan, Aritao, Nueva Vizcaya T-147044- 7,949 sq. m.- Riceland 357.934.88 Bayagung, Canarem, Aritao, N.V. -

Harnessing Rural Radio for Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation in the Philippines

Harnessing Rural Radio for Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation in the Philippines Working Paper No. 275 CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) Rex L. Navarro Renz Louie V. Celeridad Rogelio P. Matalang Hector U. Tabbun Leocadio S. Sebastian 1 Harnessing Rural Radio for Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation in the Philippines Working Paper No. 275 CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) Rex L. Navarro Renz Louie V. Celeridad Rogelio P. Matalang Hector U. Tabbun Leocadio S. Sebastian 2 Correct citation: Navarro RL, Celeridad RLV, Matalang RP, Tabbun HU, Sebastian LS. 2019. Harnessing Rural Radio for Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation in the Philippines. CCAFS Working Paper no. 275. Wageningen, the Netherlands: CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). Available online at: www.ccafs.cgiar.org Titles in this Working Paper series aim to disseminate interim climate change, agriculture and food security research and practices and stimulate feedback from the scientific community. The CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) is a strategic partnership of CGIAR and Future Earth, led by the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT). The Program is carried out with funding by CGIAR Fund Donors, Australia (ACIAR), Ireland (Irish Aid), Netherlands (Ministry of Foreign Affairs), New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs & Trade; Switzerland (SDC); Thailand; The UK Government (UK Aid); USA (USAID); The European Union (EU); and with technical support from The International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). For more information, please visit https://ccafs.cgiar.org/donors. Contact: CCAFS Program Management Unit, Wageningen University & Research, Lumen building, Droevendaalsesteeg 3a, 6708 PB Wageningen, the Netherlands. -

Cepf Final Project Completion Report

CEPF FINAL PROJECT COMPLETION REPORT I. BASIC DATA Organization Legal Name: Cagayan Valley Partners in People Development Project Title (as stated in the grant agreement): Design and Management of the Northeastern Cagayan Conservation Corridor Implementation Partners for this Project: Project Dates (as stated in the grant agreement): December 1, 2004 – June 30, 2007 Date of Report (month/year): August 2007 II. OPENING REMARKS Provide any opening remarks that may assist in the review of this report. Civil society -non-government organizations and people’s organizations, together with the academe and the church- have long been in the forefront of environmental protection in the Cagayan Valley region since the 1990s. They were and still are very active in the multi-sectoral forest protection committee and community-based forest resource management (CBFM) activities. A shift towards a conservation orientation came as a natural consequence of the Rio Summit and in view of the observation that biodiversity conservation was a neglected component of CBFM. Aside from this, there began to be implemented in region 02 biodiversity conservation projects under the CPPAP- GEF, Dutch assisted conservation and development project all in Isabela and the German assisted CBFM and Conservation project in the province of Quirino. Alongside with this was the push for the corridor approach. The CEPF assisted project is a conservation initiative that has come just at the right time when there was an upswing of interest in Cagayan in biodiversity conservation and environment protection. It came as a conservation felt need for the province of Cagayan in view of the successful pro-active actions in the neighboring province of Isabela which led to the establishment of the Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park. -

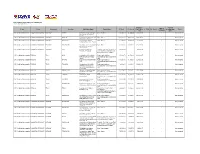

List of KALAHI-CIDSS Subprojects - MAKILAHOK As of February 01, 2019

List of KALAHI-CIDSS Subprojects - MAKILAHOK as of February 01, 2019 Estimated Physical Date of Region Province Municipality Barangay Sub-Project Name Project Type KC Grant LCC Amount Total Project No. Of HHsDate Started Accomplishme Status Completion Cost nt (%) CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA ANABEL Construction of One Unit One School Building 1,181,886.33 347,000.00 1,528,886.33 / / Not yet started Storey Elementary School Building CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA BEKIGAN Construction of Sumang-Paitan Water System 1,061,424.62 300,044.00 1,361,468.62 / / Not yet started Village Water System CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA BELWANG Construction of Pikchat- Water System 471,920.92 353,000.00 824,920.92 / / Not yet started Pattiging Village Water System CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA SACASACAN Rehabilitation of Penged Maballi- Water System 312,366.54 845,480.31 1,157,846.85 / / Not yet started Sacasshak Village Water Supply System CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]MOUNTAIN PROVINCE SADANGA SACLIT Improvement of Wetig- Footpath / Foot Trail / Access Trail 931,951.59 931,951.59 / / Not yet started Takchangan Footpath (may include box culvert/drainage as a component for Footpath) CAR [Cordillera Administrative Region]IFUGAO TINOC AHIN Construction of 5m x 1000m Road (may include box 251,432.73 981,708.84 1,233,141.57 / / Not yet started FMR Along Telep-Awa-Buo culvert/drainage as a component for Section road) -

Oryza Sativa) Cultivation in the Ifugao Rice Terraces, Philippine Cordilleras

Plant Microfossil Results from Old Kiyyangan Village: Looking for the Introduction and Expansion of Wet-field Rice (Oryza sativa) Cultivation in the Ifugao Rice Terraces, Philippine Cordilleras Mark HORROCKS, Stephen ACABADO, and John PETERSON ABSTRACT Pollen, phytolith, and starch analyses were carried out on 12 samples from two trenches in Old Kiyyangan Village, Ifugao Province, providing evidence for human activity from ca. 810–750 cal. B.P. Seed phytoliths and endosperm starch of cf. rice (Oryza sativa), coincident with aquatic Potamogeton pollen and sponge spicule remains, provide preliminary evidence for wet-field cultivation of rice at the site. The first rice remains appear ca. 675 cal. B.P. in terrace sediments. There is a marked increase in these remains after ca. 530–470 cal. B.P., supporting previous studies suggesting late expansion of the cultivation of wet-field rice in this area. The study represents initial, sediment-derived, ancient starch evidence for O. sativa, and initial, sediment-derived, ancient phytolith evidence for this species in the Philippines. KEYWORDS: Philippines, Ifugao Rice Terraces, rice (Oryza sativa), pollen, phytoliths, starch. INTRODUCTION THE IFUGAO RICE TERRACES IN THE CENTRAL CORDILLERAS,LUZON, were inscribed in the UNESCOWorldHeritage List in 1995, the first ever property to be included in the cultural landscape category of the list (Fig. 1). The nomination and subsequent listing included discussion on the age of the terraces. The terraces were constructed on steep terrains as high as 2000 m above sea level, covering extensive areas. The extensive distribution of the terraces and estimates of the length of time required to build these massive landscape modifications led some researchers to propose a long history of up to 2000–3000 years, which was supported by early archaeological 14C evidence (Barton 1919; Beyer 1955; Maher 1973, 1984). -

Sitecode Year Region Penro Cenro Province

***Data is based on submitted maps per region as of January 8, 2018. AREA IN SITECODE YEAR REGION PENRO CENRO PROVINCE MUNICIPALITY BARANGAY DISTRICT NAME OF ORGANIZATION SPECIES COMMODITY COMPONENT TENURE HECTARES 11-020900-0001-0000 2011 II Batanes Batanes Basco Chanarian Lone District 0.05 Tukon Elementary School Mango, Guyabano & Calamansi Other Fruit Trees Agroforestry Protected Area 11-020900-0002-0000 2011 II Batanes Batanes Basco Chanarian Lone District 0.08 Chanarian Elementary School Mango, Guyabano & Calamansi Other Fruit Trees Agroforestry Protected Area 11-020900-0003-0000 2011 II Batanes Batanes Itbayat Raele Lone District 0.08 Raele Barrio School Mango, Guyabano & Calamansi Other Fruit Trees Fruit trees Protected Area 11-020900-0004-0000 2011 II Batanes Batanes Uyugan Itbud Lone District 0.16 Batanes General Comprehensive High School Mango, Guyabano & Calamansi Other Fruit Trees Fruit trees Protected Area 11-020900-0005-0000 2011 II Batanes Batanes Sabtang Savidug Lone District 0.19 Savidug Barrio School (lot 2) Mango, Guyabano & Calamansi Other Fruit Trees Agroforestry Protected Area 11-020900-0006-0000 2011 II Batanes Batanes Sabtang Nakanmuan Lone District 0.20 Nakanmuan Barrio School Mango, Guyabano & Calamansi Other Fruit Trees Agroforestry Protected Area 11-020900-0007-0000 2011 II Batanes Batanes Basco San Antonio Lone District 0.27 Diptan Elementary School Mango, Guyabano & Calamansi Other Fruit Trees Agroforestry Protected Area 11-020900-0008-0000 2011 II Batanes Batanes Basco San Antonio Lone District 0.27 DepEd -

MAKING the LINK in the PHILIPPINES Population, Health, and the Environment

MAKING THE LINK IN THE PHILIPPINES Population, Health, and the Environment The interconnected problems related to population, are also disappearing as a result of the loss of the country’s health, and the environment are among the Philippines’ forests and the destruction of its coral reefs. Although greatest challenges in achieving national development gross national income per capita is higher than the aver- goals. Although the Philippines has abundant natural age in the region, around one-quarter of Philippine fami- resources, these resources are compromised by a number lies live below the poverty threshold, reflecting broad social of factors, including population pressures and poverty. The inequity and other social challenges. result: Public health, well-being and sustainable develop- This wallchart provides information and data on crit- ment are at risk. Cities are becoming more crowded and ical population, health, and environmental issues in the polluted, and the reliability of food and water supplies is Philippines. Examining these data, understanding their more uncertain than a generation ago. The productivity of interactions, and designing strategies that take into the country’s agricultural lands and fisheries is declining account these relationships can help to improve people’s as these areas become increasingly degraded and pushed lives while preserving the natural resource base that pro- beyond their production capacity. Plant and animal species vides for their livelihood and health. Population Reference Bureau 1875 Connecticut Ave., NW, Suite 520 Washington, DC 20009 USA Mangroves Help Sustain Human Vulnerability Coastal Communities to Natural Hazards Comprising more than 7,000 islands, the Philippines has an extensive coastline that is a is Increasing critical environmental and economic resource for the nation. -

Tropical Storm

PHILIPPINES - Tropical Storm "Ondoy", Typhoon "Pepeng and Santi" - Affected Regions (as of 11 November 2009, SitRep 47 and 08 November 2009, NDCC SitRep 16) 120°E 121°E 122°E 123°E 124°E 125°E 126°E Typhoon "Santi" (landfall: October 31, 2009) Legend affected over 657,751 people across 1,148 barangays Regional Boundary in 22 cities and 126 municipalities of 13 provinces in ´ Provincial Boundary Regions III, IVA, IVB, V and NCR. Around 47, 909 RIZAL people were pre-emptively evacuated across 152 QUEZON "Ondoy, Pepeng & Santi" ILOCOS NORTE evacuation centres. "Ondoy & Pepeng" "Ondoy & Santi" APAYAO Typhoon "Pepeng" (landfall: October 3, 2009) affected over 4,478,284 people across 5,486 18°N "Pepeng & Santi" 18°N CAGAYAN barangays in 36 cities and 364 municipalities of 27 Tropical Storm "Ondoy" provinces in Regions I to VI, CAR and NCR. Around Typhoon "Pepeng" Region II 14,892 people are still inside 54 evacuation centres. Typhoon "Santi" ABRA Tropical Storm "Ondoy" (landfall: September 26, 2009) affected over 4,929,382 people across KALINGA Region I 1,987 barangays in 16 cities and 172 municipalities of 26 provinces in Regions I to VI, IX, X11, ARMM, CAR Map Doc Name: ILOCOS SUR and NCR. Around 72,305 people are still inside 252 MOUNTAIN PROVINCE evacuation centers. MAO93_PHL-Combined-Ondoy&Pepeng&Santi -AftAreas-11NOv2009-A4-V01 17°N 17°N Source: National Disaster Coordinating Council (NDCC), Philippines CAVITE Laguna de Bay Glide No.: TC-2009-000205-PHL CAR TC-2009-000214-PHL TC-2009-000230-PHL ISABELA Creation Date: 11 November 2009 LA UNION Projection/Datum: UTM/Luzon Datum BENGUET Web Resources: http://www.un.org.ph/response/ NUEVA VIZCAYA QUIRINO LAGUNA Best printed at A4 paper size PHILIPPINE SEA PANGASINAN A 16°N Data sources: 16°N BATANGAS AURORA NSCB - (www.nscb.gov.ph). -

Chronic Food Insecurity Situation Overview in 71 Provinces of the Philippines 2015-2020

Chronic Food Insecurity Situation Overview in 71 provinces of the Philippines 2015-2020 Key Highlights Summary of Classification Conclusions Summary of Underlying and Limiting Factors Out of the 71 provinces Severe chronic food insecurity (IPC Major factors limiting people from being food analyzed, Lanao del Sur, level 4) is driven by poor food secure are the poor utilization of food in 33 Sulu, Northern Samar consumption quality, quantity and provinces and the access to food in 23 provinces. and Occidental Mindoro high level of chronic undernutrition. Unsustainable livelihood strategies are major are experiencing severe In provinces at IPC level 3, quality of drivers of food insecurity in 32 provinces followed chronic food insecurity food consumption is worse than by recurrent risks in 16 provinces and lack of (IPC Level 4); 48 quantity; and chronic undernutrition financial capital in 17 provinces. provinces are facing is also a major problem. In the provinces at IPC level 3 and 4, the majority moderate chronic food The most chronic food insecure of the population is engaged in unsustainable insecurity (IPC Level 3), people tend to be the landless poor livelihood strategies and vulnerable to seasonal and 19 provinces are households, indigenous people, employment and inadequate income. affected by a mild population engaged in unsustainable Low-value livelihood strategies and high chronic food insecurity livelihood strategies such as farmers, underemployment rate result in high poverty (IPC Level 2). unskilled laborers, forestry workers, incidence particularly in Sulu, Lanao del Sur, Around 64% of the total fishermen etc. that provide Maguindanao, Sarangani, Bukidnon, Zamboanga population is chronically inadequate and often unpredictable del Norte (Mindanao), Northern Samar, Samar food insecure, of which income. -

Consolidated List of Establishments – Conduct of Cles

CONSOLIDATED LIST OF ESTABLISHMENTS – CONDUCT OF CLES 1. Our Lady of Victories Academy (OLOVA) Amulung, Cagayan 2. Reta Drug Solano, Nueva Vizcaya 3. SCMC/SMCA/SATO SM Cauayan City 4. GQ Barbershop SM Cauayan City 5. Quantum SM Cauayan City 6. McDonald SM Cauayan City 7. Star Appliance Center SM Cauyan City 8. Expressions Martone Cauyan City 9. Watch Central SM Cauayan City 10. Dickies SM Cauayan City 11. Jollibee SM Cauayan City 12. Ideal Vision SM Cauayan City 13. Mendrez SM Cauayan City 14. Plains and prints SM Cauayan City 15. Memo Express SM Cauayan City 16. Sony Experia SM Cauayan City 17. Sports Zone SM Cauayan City 18. KFC Phils. SM Cauayan City 19. Payless Shoe Souref SM Cauyan City 20. Super Value Inc.(SM Supermarket) SM Cauyan City 21. Watson Cauyan City 22. Gadget @ Xtreme SM Cauyan City 23. Game Xtreme SM Cauyan City 24. Lets Face II Cauyan City 25. Cafe Isabela Cauayan City 26. Eye and Optics SM Cauayan City 27. Giordano SM Cauayan City 28. Unisilver Cabatuan, Isabela 29. NAILAHOLICS Cabatuan, Isabela 30. Greenwich Cauayan City 31. Cullbry Cauayan City 32. AHPI Cauyan City 33. LGU Reina Mercedes Reina Mercedes, Isabela 34. EGB Construction Corp. Ilagan City 35. Cauayan United Enterp & Construction Cauayan City 36. CVDC Ilagan City 37. RRJ and MR. LEE Ilagan City 38. Savers Appliance Depot Northstar Mall Ilagan city 39. Jeffmond Shoes Northstar Mall Ilagan city 40. B Club Boutique Northstar Mall Ilagan city 41. Pandayan Bookshop Inc. Northstar Mall Ilagan city 42. Bibbo Shoes Northstar Mall Ilagan city 43. -

JOSELINE “JOYCE” P. NIWANE Assistant Secretary for Policy and Plans DSWD-Central Office Batasan Pambansa Complex, Constitution Hills Quezon City

JOSELINE “JOYCE” P. NIWANE Assistant Secretary for Policy and Plans DSWD-Central Office Batasan Pambansa Complex, Constitution Hills Quezon City Personal Information Date of Birth: April 3, 1964 Place of Birth: Baguio City Marital Status: Single Parents: COL. Francisco Niwane(Ret) Mrs. Adela P. Niwane Education Elementary: Holy Family Academy, Baguio City 1971-1977 High School: Holy Family Academy, Baguio City 1977-1981 College: Saint Louis University, Baguio City 1982-1985 Post Education: 1. University of the Philippines (1989-1990) - Masters in Public Administration 2. University of Washington, Seattle, USA ( 2001-2002) -Post Graduate in Public Policy and Social Justice 3. Saint Mary’s University (2005-2006) - Masters in Public Administration AWARDS/ FELLOWSHIPS RECEVEIVED: 1986 : “Merit of Valor” Award – World Vision International 1996 : 1st Provincial AWARD OF MERIT – Provincial Government of Ifugao 1997 : Dangal ng Bayan Awardee - CSC and Pres. Fidel V. Ramos 1998 : Model Public Servant Awardee of the Year – KILOSBAYAN AND GMA 7 1998 : Outstanding Cordillera Woman of the Year – Midland Courier 1998 : 1st National Congress of Honor Awardee 2001 : Ifugao Achievers Award - Provincial Government of Ifugao 2001-2002 : Hubert Humphrey Fellowship Program/Fulbright- United States of America Government 2013 : Best Provincial Social Welfare and Dev’t. Officer – DSWD-CAR 2015 : Galing Pook Award - DILG 2016 : Gawad Gabay : Galing sa Paggabay sa mga Bata para sa Magandang Buhay “ Champion of Positive and Non-violent discipline for the Filipino -

Pdf | 308.16 Kb

2. Damaged Infrastructure and Agriculture (Tab D) Total Estimated Cost of Damages PhP 411,239,802 Infrastructure PhP 29,213,821.00 Roads & Bridges 24,800,000.00 Transmission Lines 4,413,821.00 Agriculture 382,025,981.00 Crops 61,403,111.00 HVCC 5,060,950.00 Fisheries 313,871,920.00 Facilities 1,690,000.00 No report of damage on school buildings and health facilities as of this time. D. Emergency Incidents Monitored 1. Region II a) On or about 10:00 AM, 08 May 2009, one (1) ferry boat owned by Brgy Captain Nicanor Taguba of Gagabutan, Rizal, bound to Cambabangan, Rizal, Cagayan, to attend patronal fiesta with twelve (12) passengers on board, capsized while crossing the Matalad River. Nine (9) passengers survived while three (3) are still missing identified as Carmen Acasio Anguluan (48 yrs /old), Vladimir Acasio Anguluan (7 yrs /old) and Mac Dave Talay Calibuso (5 yrs/old), all from Gagabutan East Rizal, Cagayan. The 501st Infantry Division (ID) headed by Col. Remegio de Vera, PNP personnel and some volunteers from Rizal, Cagayan conducted search and rescue operations. b) In Nueva Vizcaya, 31 barangays were flooded: Solano (16), Bagabag (5), Bayombong (4), Bambang (4), in Dupax del Norte (1) and in Dupax del Sur (1). c) Barangays San Pedro and Manglad in Maddela, Quirino were isolated due to flooding. e) The low-lying areas of Brgys Mabini and Batal in Santiago City, 2 barangays in Dupax del Norte and 4 barangays in Bambang were rendered underwater with 20 families evacuated at Bgy Mabasa Elementary School.