Use of Antiseptics in Managing Difficult Wounds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

)&F1y3x PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX to THE

)&f1y3X PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE )&f1y3X PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE TARIFF SCHEDULE 3 Table 1. This table enumerates products described by International Non-proprietary Names (INN) which shall be entered free of duty under general note 13 to the tariff schedule. The Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers also set forth in this table are included to assist in the identification of the products concerned. For purposes of the tariff schedule, any references to a product enumerated in this table includes such product by whatever name known. Product CAS No. Product CAS No. ABAMECTIN 65195-55-3 ACTODIGIN 36983-69-4 ABANOQUIL 90402-40-7 ADAFENOXATE 82168-26-1 ABCIXIMAB 143653-53-6 ADAMEXINE 54785-02-3 ABECARNIL 111841-85-1 ADAPALENE 106685-40-9 ABITESARTAN 137882-98-5 ADAPROLOL 101479-70-3 ABLUKAST 96566-25-5 ADATANSERIN 127266-56-2 ABUNIDAZOLE 91017-58-2 ADEFOVIR 106941-25-7 ACADESINE 2627-69-2 ADELMIDROL 1675-66-7 ACAMPROSATE 77337-76-9 ADEMETIONINE 17176-17-9 ACAPRAZINE 55485-20-6 ADENOSINE PHOSPHATE 61-19-8 ACARBOSE 56180-94-0 ADIBENDAN 100510-33-6 ACEBROCHOL 514-50-1 ADICILLIN 525-94-0 ACEBURIC ACID 26976-72-7 ADIMOLOL 78459-19-5 ACEBUTOLOL 37517-30-9 ADINAZOLAM 37115-32-5 ACECAINIDE 32795-44-1 ADIPHENINE 64-95-9 ACECARBROMAL 77-66-7 ADIPIODONE 606-17-7 ACECLIDINE 827-61-2 ADITEREN 56066-19-4 ACECLOFENAC 89796-99-6 ADITOPRIM 56066-63-8 ACEDAPSONE 77-46-3 ADOSOPINE 88124-26-9 ACEDIASULFONE SODIUM 127-60-6 ADOZELESIN 110314-48-2 ACEDOBEN 556-08-1 ADRAFINIL 63547-13-7 ACEFLURANOL 80595-73-9 ADRENALONE -

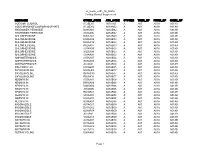

Laboratory Reagents Product List 2021

PRODUCT LIST Examples of our laboratory reagents Product list – selected products Artificial Urine Brooks and Keevil AMPQ44861.1000 Auramine-Rhodamine AMPQ55029.0500 Below is a selection of products. If you cannot find what you are look- Auric Chloride 0.1% AMPQ12450.0500 ing for, please contact us about your specific requests for laboratory reagents, volume and packaging, etc. Auric Chloride 1% AMPQ12452.0100 We mainly use chemicals by p.a. quality. If you want growth control on growing media, please contact us for an offer. B Balanced Salt Solution for Storage AMPQ46214.0100 Product name Cat. No. Balanced Salt Solution with Tris AMPQ40040.1000 Barium Chloride 0.5 M = 1.0 N AMPQ42099.1000 2,4-Dinitroflouro Benzen 1.3% v/v AMPQ44913.0100 Barium Chloride 1 M AMPQ43551.0500 2-Amino-2-Methyl-1,3-propanediol 2.1 % w/v AMPQ42009.0250 Barium Chloride 10% w/v AMPQ10513.1000 2-Propanol 35% AMPQ12900.5000 Barium Diphenylamine Sulfonate AMPQ40838.0500 Basophil Counting Solution AMPQ90492.0200 A Basophilic Colouring Solution AMPQ42037.0100 Acetate Buffer 0.1 M, pH 4.0 AMPQ10021.1000 Benzamidine 0.5 M in MilliQ H2O AMPQ10750.0100 Acetate Buffer 0.1 M, pH 4.8 AMPQ40728.1000 Benzoe I Colouring Solution AMPQ10779.0100 Acetate Buffer 0.1 M, pH 5.9 AMPQ43009.1000 Benzoe II Colouring Solution AMPQ10781.0100 Acetate Buffer 35%, pH 5.6 AMPQ10015.1000 Biebrich Scarlet Solution AMPQ46088.1000 Acetate Buffer Walpole pH 4.1 AMPQ55005.0500 Biebrich's Scarlet Acid Fuchsin AMPQ29082.0500 Acetic Acid 0.1 M Titrated AMPQ11590.5000 Bies Colouring Solution AMPQ10780.0050 Acetic Acid 1% AMPQ11515.1000 BiGGY Agar AMPQ02048.0015 Acetic Acid 10% P.A. -

Guideline for Disinfection and Sterilization in Healthcare Facilities, 2008

Guideline for Disinfection and Sterilization in Healthcare Facilities, 2008 Guideline for Disinfection and Sterilization in Healthcare Facilities, 2008 William A. Rutala, Ph.D., M.P.H.1,2, David J. Weber, M.D., M.P.H.1,2, and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC)3 1Hospital Epidemiology University of North Carolina Health Care System Chapel Hill, NC 27514 2Division of Infectious Diseases University of North Carolina School of Medicine Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7030 1 Guideline for Disinfection and Sterilization in Healthcare Facilities, 2008 3HICPAC Members Robert A. Weinstein, MD (Chair) Cook County Hospital Chicago, IL Jane D. Siegel, MD (Co-Chair) University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Dallas, TX Michele L. Pearson, MD (Executive Secretary) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Atlanta, GA Raymond Y.W. Chinn, MD Sharp Memorial Hospital San Diego, CA Alfred DeMaria, Jr, MD Massachusetts Department of Public Health Jamaica Plain, MA James T. Lee, MD, PhD University of Minnesota Minneapolis, MN William A. Rutala, PhD, MPH University of North Carolina Health Care System Chapel Hill, NC William E. Scheckler, MD University of Wisconsin Madison, WI Beth H. Stover, RN Kosair Children’s Hospital Louisville, KY Marjorie A. Underwood, RN, BSN CIC Mt. Diablo Medical Center Concord, CA This guideline discusses use of products by healthcare personnel in healthcare settings such as hospitals, ambulatory care and home care; the recommendations are not intended for consumer use of the products discussed. 2 -

The International Pharmacopoeia

The International Pharmacopoeia THIRD EDITION Pharmacopoea internationalis Editio tertia Volume 4 Tests, methods, and general requirements Quality specifications for pharmaceutical substances, excipients, and dosage forms World Health Organization Geneva 1994 WHO Library Cataloguing in Publication Data The International Pharmacopoeia.- 3rd ed. Contents: v. 4. Tests, methods, and general requirements 1. Drugs -analysis 2. Drugs -standards ISBN 92 4 154462 7 (NLM Classification: QV 25) The World Health Organization welcomes requests for permission to reproduce or translate its publica- tions, in part or in full. Applications and enquiries should be addressed to the Of£ice of Publications, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, which will be glad to provide the latest information on any changes made to the text, plans for new editions, and reprints and translations already available. O World Health Organization, 1994 Publications of the World Health Organization enjoy copyright protection in accordance with the provi- sions of Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers' products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distin- guished by initial capital letters. -

Australian Statistics on Medicines 1997 Commonwealth Department of Health and Family Services

Australian Statistics on Medicines 1997 Commonwealth Department of Health and Family Services Australian Statistics on Medicines 1997 i © Commonwealth of Australia 1998 ISBN 0 642 36772 8 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be repoduced by any process without written permission from AusInfo. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be directed to the Manager, Legislative Services, AusInfo, GPO Box 1920, Canberra, ACT 2601. Publication approval number 2446 ii FOREWORD The Australian Statistics on Medicines (ASM) is an annual publication produced by the Drug Utilisation Sub-Committee (DUSC) of the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee. Comprehensive drug utilisation data are required for a number of purposes including pharmacosurveillance and the targeting and evaluation of quality use of medicines initiatives. It is also needed by regulatory and financing authorities and by the Pharmaceutical Industry. A major aim of the ASM has been to put comprehensive and valid statistics on the Australian use of medicines in the public domain to allow access by all interested parties. Publication of the Australian data facilitates international comparisons of drug utilisation profiles, and encourages international collaboration on drug utilisation research particularly in relation to enhancing the quality use of medicines and health outcomes. The data available in the ASM represent estimates of the aggregate community use (non public hospital) of prescription medicines in Australia. In 1997 the estimated number of prescriptions dispensed through community pharmacies was 179 million prescriptions, a level of increase over 1996 of only 0.4% which was less than the increase in population (1.2%). -

Vr Meds Ex01 3B 0825S Coding Manual Supplement Page 1

vr_meds_ex01_3b_0825s Coding Manual Supplement MEDNAME OTHER_CODE ATC_CODE SYSTEM THER_GP PHRM_GP CHEM_GP SODIUM FLUORIDE A12CD01 A01AA01 A A01 A01A A01AA SODIUM MONOFLUOROPHOSPHATE A12CD02 A01AA02 A A01 A01A A01AA HYDROGEN PEROXIDE D08AX01 A01AB02 A A01 A01A A01AB HYDROGEN PEROXIDE S02AA06 A01AB02 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE B05CA02 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE D08AC02 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE D09AA12 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE R02AA05 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE S01AX09 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE S02AA09 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE S03AA04 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB AMPHOTERICIN B A07AA07 A01AB04 A A01 A01A A01AB AMPHOTERICIN B G01AA03 A01AB04 A A01 A01A A01AB AMPHOTERICIN B J02AA01 A01AB04 A A01 A01A A01AB POLYNOXYLIN D01AE05 A01AB05 A A01 A01A A01AB OXYQUINOLINE D08AH03 A01AB07 A A01 A01A A01AB OXYQUINOLINE G01AC30 A01AB07 A A01 A01A A01AB OXYQUINOLINE R02AA14 A01AB07 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN A07AA01 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN B05CA09 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN D06AX04 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN J01GB05 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN R02AB01 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN S01AA03 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN S02AA07 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN S03AA01 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE A07AC01 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE D01AC02 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE G01AF04 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE J02AB01 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE S02AA13 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB NATAMYCIN A07AA03 A01AB10 A A01 -

Antiseptic Cytotoxicity and the Cutaneous Wound: an in Vitro Study

mill llll ill iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii ii h i mu 2807400138 ANTISEPTIC CYTOTOXICITY AND THE CUTANEOUS WOUND: AN IN VITRO STUDY Frances Melanie Tatnall MB BS, London 1978 Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Medicine Department of Dermatology The Royal London Hospital London E l IBB Submitted: April 1991 MEDICAL LIBRARY. ROYAL FREE HOSPITA l HAMPSTEAD ProQuest Number: U553699 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest U553699 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT Concern has been expressed about the possible harmful effects of antiseptics on cutaneous wounds. There are few clinical data to support this view but animal studies suggest that certain agents are toxic. To simplify the investigation of antiseptic toxicity investigations have been conducted in vitro using cell culture. This study set out to establish an in vitro cytotoxicity assay which is simple, accurate and reliable, so that a number of cell types and agents could be easily studied. Basal keratinocytes and fibroblasts were studied as these cells are essential to the wound healing process. -

Ajax Finechem Product Catalogue 3510 585 6

ACE AJAX FINECHEM PRODUCT CATALOGUE 3510 ACETONE, HPLC GRADE, BURDICK & JACKSON, CAT. AH010 Assay ……………………………………………………….. 99.9% min. Maximum limit of impurities (%) Water ……………………………………………………….. 0.5 Residue ……………………………………………………… 3mg/L Max. UV. Absorbance: λ(nm) 330 340 350 375 400 Absorbance 1.000 0.080 0.010 0.005 0.005 Pack Size: 4L 585 ACETONE, SPECTROSOL Description: clear liquid; characteristic odour. For U.V. spectroscopy. Assay (by GLC) ……………………………………………….. 99.5% min. Colour (APHA) …………………………………............ 10 max. Density (@ 25°C ) ……………………………………… 0.7857g/mL max. U.V absorbance λ(nm) 330 340 350 400 Max abs. 1.00 0.1 0.02 0.01 Maximum limit of impurities (%) R.A.E. ……………………………………………………….. 0.001 Sol. in H2O ………………………………………………… To pass test Titratable acid …………………………………………… 0.03 mmol H Titratable base ………………………………………….. 0.06 mmol OH Aldehyde (as HCHO) ………………………………….. 0.002 CH3OH ………………………………………………………. 0.05 Propan-2-ol ……………………………………………….. 0.05 Subs. red. KMnO4 (as O) …………………………….. 0.0005 H2O ………………………………………………………….. 0.5 Conforms to ACS Pack Size: 500mL 6 ACETONE, UNIVAR Description: clear liquid with a characteristic odour. Assay( by GLC) ………………………………………….. 99.5% min. Colour (APHA) …………………………………………… 10 max. Density (@ 25oC) ……………………………….......... 0.7857g/mL max. Maximum limit of impurities (%) R.A.E. ……………………………………………………….. 0.001 Cd …………………………………………………. 0.000005 Sol. in H2O …………………………………………………. To pass test Pb ………………………………………………….. 0.000005 Titratable acid ……………………………………………. 0.03 mmol H Ca………………………………………………….. 0.00005 Titratable base …………………………………………… 0.06 mmol OH Zn ………………………………………………….. 0.00005 Aldehyde (as HCHO) …………………………………… 0.002 Na …………………………………………………. 0.00005 Methanol, Propan-2-ol (each) ………………………. 0.05 K …………………………………………………….. 0.00005 Fe …………………………………………………………….. 0.00002 Cr…………………………………………………… 0.000002 Subs. red. KMnO4`……………………………………….. To pass test Co ………………………………………………….. 0.000002 H2O …………………………………………………………… 0.5 Cu ………………………………………………….. 0.000002 Al ……………………………………………………………… 0.00001 Mn …………………………………………………. -

Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 80 / Wednesday, April 26, 1995 / Notices DIX to the HTSUS—Continued

20558 Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 80 / Wednesday, April 26, 1995 / Notices DEPARMENT OF THE TREASURY Services, U.S. Customs Service, 1301 TABLE 1.ÐPHARMACEUTICAL APPEN- Constitution Avenue NW, Washington, DIX TO THE HTSUSÐContinued Customs Service D.C. 20229 at (202) 927±1060. CAS No. Pharmaceutical [T.D. 95±33] Dated: April 14, 1995. 52±78±8 ..................... NORETHANDROLONE. A. W. Tennant, 52±86±8 ..................... HALOPERIDOL. Pharmaceutical Tables 1 and 3 of the Director, Office of Laboratories and Scientific 52±88±0 ..................... ATROPINE METHONITRATE. HTSUS 52±90±4 ..................... CYSTEINE. Services. 53±03±2 ..................... PREDNISONE. 53±06±5 ..................... CORTISONE. AGENCY: Customs Service, Department TABLE 1.ÐPHARMACEUTICAL 53±10±1 ..................... HYDROXYDIONE SODIUM SUCCI- of the Treasury. NATE. APPENDIX TO THE HTSUS 53±16±7 ..................... ESTRONE. ACTION: Listing of the products found in 53±18±9 ..................... BIETASERPINE. Table 1 and Table 3 of the CAS No. Pharmaceutical 53±19±0 ..................... MITOTANE. 53±31±6 ..................... MEDIBAZINE. Pharmaceutical Appendix to the N/A ............................. ACTAGARDIN. 53±33±8 ..................... PARAMETHASONE. Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the N/A ............................. ARDACIN. 53±34±9 ..................... FLUPREDNISOLONE. N/A ............................. BICIROMAB. 53±39±4 ..................... OXANDROLONE. United States of America in Chemical N/A ............................. CELUCLORAL. 53±43±0 -

Bulk Drug Substances Nominated for Use in Compounding Under Section 503B of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act

Updated June 07, 2021 Bulk Drug Substances Nominated for Use in Compounding Under Section 503B of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act Three categories of bulk drug substances: • Category 1: Bulk Drug Substances Under Evaluation • Category 2: Bulk Drug Substances that Raise Significant Safety Risks • Category 3: Bulk Drug Substances Nominated Without Adequate Support Updates to Categories of Substances Nominated for the 503B Bulk Drug Substances List1 • Add the following entry to category 2 due to serious safety concerns of mutagenicity, cytotoxicity, and possible carcinogenicity when quinacrine hydrochloride is used for intrauterine administration for non- surgical female sterilization: 2,3 o Quinacrine Hydrochloride for intrauterine administration • Revision to category 1 for clarity: o Modify the entry for “Quinacrine Hydrochloride” to “Quinacrine Hydrochloride (except for intrauterine administration).” • Revision to category 1 to correct a substance name error: o Correct the error in the substance name “DHEA (dehydroepiandosterone)” to “DHEA (dehydroepiandrosterone).” 1 For the purposes of the substance names in the categories, hydrated forms of the substance are included in the scope of the substance name. 2 Quinacrine HCl was previously reviewed in 2016 as part of FDA’s consideration of this bulk drug substance for inclusion on the 503A Bulks List. As part of this review, the Division of Bone, Reproductive and Urologic Products (DBRUP), now the Division of Urology, Obstetrics and Gynecology (DUOG), evaluated the nomination of quinacrine for intrauterine administration for non-surgical female sterilization and recommended that quinacrine should not be included on the 503A Bulks List for this use. This recommendation was based on the lack of information on efficacy comparable to other available methods of female sterilization and serious safety concerns of mutagenicity, cytotoxicity and possible carcinogenicity in use of quinacrine for this indication and route of administration. -

Estonian Statistics on Medicines 2013 1/44

Estonian Statistics on Medicines 2013 DDD/1000/ ATC code ATC group / INN (rout of admin.) Quantity sold Unit DDD Unit day A ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 146,8152 A01 STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 0,0760 A01A STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 0,0760 A01AB Antiinfectives and antiseptics for local oral treatment 0,0760 A01AB09 Miconazole(O) 7139,2 g 0,2 g 0,0760 A01AB12 Hexetidine(O) 1541120 ml A01AB81 Neomycin+Benzocaine(C) 23900 pieces A01AC Corticosteroids for local oral treatment A01AC81 Dexamethasone+Thymol(dental) 2639 ml A01AD Other agents for local oral treatment A01AD80 Lidocaine+Cetylpyridinium chloride(gingival) 179340 g A01AD81 Lidocaine+Cetrimide(O) 23565 g A01AD82 Choline salicylate(O) 824240 pieces A01AD83 Lidocaine+Chamomille extract(O) 317140 g A01AD86 Lidocaine+Eugenol(gingival) 1128 g A02 DRUGS FOR ACID RELATED DISORDERS 35,6598 A02A ANTACIDS 0,9596 Combinations and complexes of aluminium, calcium and A02AD 0,9596 magnesium compounds A02AD81 Aluminium hydroxide+Magnesium hydroxide(O) 591680 pieces 10 pieces 0,1261 A02AD81 Aluminium hydroxide+Magnesium hydroxide(O) 1998558 ml 50 ml 0,0852 A02AD82 Aluminium aminoacetate+Magnesium oxide(O) 463540 pieces 10 pieces 0,0988 A02AD83 Calcium carbonate+Magnesium carbonate(O) 3049560 pieces 10 pieces 0,6497 A02AF Antacids with antiflatulents Aluminium hydroxide+Magnesium A02AF80 1000790 ml hydroxide+Simeticone(O) DRUGS FOR PEPTIC ULCER AND GASTRO- A02B 34,7001 OESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE (GORD) A02BA H2-receptor antagonists 3,5364 A02BA02 Ranitidine(O) 494352,3 g 0,3 g 3,5106 A02BA02 Ranitidine(P) -

Assessment of the Antibiotic Resistance Effects of Biocides

Scientific Committee on Emerging and Newly Identified Health Risks SCENIHR Assessment of the Antibiotic Resistance Effects of Biocides The SCENIHR adopted this opinion at the 28th plenary on 19 January 2009 after public consultation. 1 Antibiotic Resistance Effects of Biocides About the Scientific Committees Three independent non-food Scientific Committees provide the Commission with the scientific advice it needs when preparing policy and proposals relating to consumer safety, public health and the environment. The Committees also draw the Commission's attention to the new or emerging problems which may pose an actual or potential threat. They are: the Scientific Committee on Consumer Products (SCCP), the Scientific Committee on Health and Environmental Risks (SCHER) and the Scientific Committee on Emerging and Newly Identified Health Risks (SCENIHR), and are made up of external experts. In addition, the Commission relies upon the work of the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), the European Medicines Evaluation Agency (EMEA), the European Centre for Disease prevention and Control (ECDC) and the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA). SCENIHR Questions concerning emerging or newly-identified risks and on broad, complex or multi- disciplinary issues requiring a comprehensive assessment of risks to consumer safety or public health and related issues not covered by other Community risk-assessment bodies. In particular, the Committee addresses questions related to potential risks associated with interaction of risk factors, synergic effects, cumulative effects, antimicrobial resistance, new technologies such as nanotechnologies, medical devices, tissue engineering, blood products, fertility reduction, cancer of endocrine organs, physical hazards such as noise and electromagnetic fields and methodologies for assessing new risks.