Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drought and Livestock in Semi-Arid Africa and Southwest Asia

Working Paper 117 DROUGHT AND LIVESTOCK IN SEMI-ARID AFRICA AND SOUTHWEST ASIA Roger Blench Zoë Marriage March 1999 Overseas Development Institute Portland House Stag Place London SW1E 5DP Acknowledgements The first version of this paper and the annotated bibliography was prepared as a keynote document for the FAO-sponsored Electronic Conference ‘Drought and livestock in semi-arid Africa and the Near East’, which took place between July and September 1998. The papers from the conference can be accessed at http://www.fao.org/ag/aga/agap/lps/drought1.htm. The authors are grateful to all those who took part in the conference, and the revision of this document reflects both specific comments on the text and some of the general discussion that formed part of the conference. We would like to thank Andy Catley, Maryam Fuller and Simon Mack for their observations and additional references; we hope their concerns are reflected in this revised text. This working paper is distributed by the Overseas Development Institute (ODI), an independent, non-profit policy research institute, with financial support from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and the Natural Resources Institute (NRI) under funding from the Department for International Development. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of ODI, FAO, NRI or the Department for International Development. Roger Blench ([email protected]) is a Research Fellow, and Zoë Marriage (z.marriage@ odi.org.uk) is a Research Assistant, at the Overseas Development Institute. Editing, index and layout by Paul Mundy, Weizenfeld 4, 51467 Bergisch Gladbach, Germany; [email protected], http://www.netcologne.de/~nc-mundypa ISBN 0 85003 416 7 © Overseas Development Institute 1999 All rights reserved. -

AU MALI at T.Ichmnots a 1

USAID MALI;,____ AMBASSADE AMERICAINS IR U9mako (I.D. USAID/Bamako AU6 31 o state BP. 34 nton D.C. 20520 Bamako.Mex 448 T61. 22-3602 Tilex 448v; Mr. Larry Johnson World Vision Belief & Development Ine. 919 West Huntington Drive Monrovia, California 91010 Subject: Grant No 00-0128-00 Dear Mr. Johnson: Pursuant to the authority contained in the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as a:nendedp the Agency for International Development (hereinafter referred to as "A.I.D.") hereby grants World Vision Relief & Development Inc. in Mali (hereby referred to as "tWil)" or the "Recipient"), the awn of $150p000 to. provide technical assistance as outlined in Attachment Two, "Program Description" and Attachiment One, "Schedule." This Grant is made effective and obligation is made as of the date of this letter and shall apply to commitments made by the Recipient in furtherance of program objectives during the period beginni-ng with the effective date and ending March 31, 1990. This Grant is made-to WVIID on condition that the funds will be administered in accordance with the terms and conditions as set forth in Attachment 1, entitled "Sched~ule", Attachment 2, ontitled "Program Description," and Attachment 3 entitled "Standard Provisions," which have been agread to by your organization. Please sign the original and seven (7) copies of this letter to acknowledge your receipt of the Grant, and return the original and six.(6) copies to the Agreement Office listed below. Sincerely yours, in 1 20521-2050 AU MALI At t.ichmnots a 1. Seliiulo 2. Irogrn Jloseript ion 3. -

FEWS Country Report MALI

Report Number 8 Jaiuary 1987 FEWS Country Report MALI Africa Bureau U.S. Agency for International Development M&P 1: MALI Summary Map Bourem Cercle At--Rixk: 60,000 Immediate Food Aid Need: 2,700 wr Monake Cercle At-Risk: 18,000 Immediate Food Aid Need: 800 Ir Douentza Cercle At-Risk: 162,000 (131,000) Nara Cercl.eI At-Risk: 140,0005 Immnediate FFood Aid 2,700 1T Need: Youverou Cercier At-Risk 9(,OOA At-Ri-k: 94.000 5 YouvertuCerc l S Bandiagara Cercie At-Risk: 141,000 At-Risk- 180,000 N Immediate food aid need computed at 42kg per person for 3 month period. FEWS/PWA, January 1957 Famine Early Warning System Country Report MALI At-Risk Update: Focus on Gao Prepared for the Africa Bureau of the U.S. Agency for International Development Prepared by Price, Williams & Associates, Inc. January 1987 Contents Page i Introduction 1 Summary 2 Population At-Risk 6 Displaced Persons 6 Health and Nutrition 7 Market Prices 7 Food Aid List of Fipurc-s Pa ge 2 Map 2 Gao At-Risk 4 Map 3 Tombouctou At-Risk 5 Map 4 Mopti At-Risk Back Map 5 Administrative Units Cover a series of monthly reports issued INTRODUCTION This is the eighth of by the Famine Early Warning System (FEWS) on Mali, to current as of January 10, 1987. it is designed and provide decisionmakers with current infor-mation analysis on existi.ng and potential nutrition emergency in situations. Each situation identified is described of people terms of geographical extent and the number insofar as involved, or at-risk, and the proximate causes they have been discerned. -

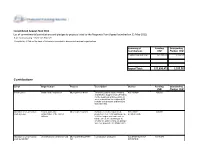

Contributions

Consolidated Appeal: Mali 2012 List of commitments/contributions and pledges to projects listed to the Response Plan (Appeal launched on 31-May-2012) http://fts.unocha.org (Table ref: ReportF) Compiled by OCHA on the basis of information provided by donors and recipient organizations. Summary of Funding Outstanding Contributions USD Pledges USD Contributions sub total: 152,898,473 3,255,587 Appeal Total: 152,898,473 3,255,587 Contributions Donor Organization Project Description Cluster Funding Outstanding USD Pledges USD African Union World Food Programme MLI-12/H/50679/561 Targeted Supplementary Feeding NUTRITION 100,000 and Blanket Supplementary Feeding for the treatment and prevention of acute malnutrition for children 6-59 months and pregnant and lactating women in Mali Allocation of unearmarked Food & Agriculture MLI-12/A/51154/123 Renforcement des capacités de SECURITE 500,000 funds by FAO Organization of the United production et de l’état nutritionnel de ALIMENTAIRE Nations 5 000 ménages vulnérables de la bande sahélienne du Mali par la création de jardins villageois potager- vivrier de proximité (TCP/MLI/3401) Allocation of unearmarked United Nations Children's Fund MLI-12/SNYS/52278/R/ Humanitarian assistance CLUSTER NOT YET 1,049,979 funds by UNICEF 124 SPECIFIED Allocation of unearmarked World Food Programme MLI-12/F/50675/561 Food Assistance (Multilateral funds) SECURITE 15,184,429 funds by WFP ALIMENTAIRE Americares International Organization for MLI-12/WS/50795/298 Improved Access to Safe Water EAU-HYGIENE- 108,519 Migration -

An Overview of the Food Consumption and Nutrition Situation in Mali

An Overview of the Food Consumption and Nutrition Situation in Mali Report submitted to USAID/Mali, Agricultural Development Office by Shelly Sundberg Final March 1988 Table of Contents List of Tables and Figures ii List cf Abbreviations Used iii Executive Summary v I. Introduction 1 II. Overview of the Food Balance Situation 4 A. Calculation of the Annual Per Capita Cereals Requirement 4 B. Regional Cereals Surplus/Deficit Situation 6 III. Food Consumption Patterns 8 A. Regional and Ethnic Group Variation 8 1. Rural Sedentary Diets 9 2. Urban Diets 10 3. Diets of Nomadic Populations 11 B. Child Feeding Practices 12 C. Dietary Restrictions 13 IV. Prevalence of Malnutrition 15 A. Protein-Energy Malnutrition 15 1. Acute Protein-Energy Malnutrition 17 a. Prevalence Studies 17 b. Affected Population 24 2. Chronic Protein-Energy Malnutrition 26 B. Vitamin and Mineral Deficiencies 28 1. Vitamin A 28 2. Vitamin C 28 3. Anemia 29 4. Goiter 29 V. Food Consumption Strategies in Response to Changes in Production and Income 30 A. Coping Strategies in Rural Areas in Response to Production Shortfalls 30 B. Characteristics of Rural Households which Survive Poor Production Years with Minimal Effects on Food Consumption 33 C. Effect of Economic Policy Changes on Food Consumption 35 VI. Conclusion 39 Bibliography 41 Annex I People Contacted in Mali and Documentation Centers Consulted in Bamako 51 Annex II Current Nutrition and Consumption Data Collection Efforts in Mali 53 List of Tables and Figures Tables Table 1 Estimation of Annual Per Capita Cereals -

DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX (DTM) April 2014

Photo Juliana Quintero Mali DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX (DTM) April 2014 Introduction Key Findings IOM, in close collaboration with the Ministry of Solidarity, 26,761 households (137,096 internally Humanitarian Affairs and Reconstruction in the North as well as the displaced persons) registered and assessed by Ministry of Interior and Security began, in June 2012, its Displacement IOM in all regions in Mali. 79,843 IDPs in the Tracking Matrix Program (DTM) with the objective to collect data on south and 57,253 IDPs in the north. populations affected by the 2012 conflict. IDPs’ movement toward the northern The methodology and tools used by the DTM program were regions continue, even if they slow down elaborated by the Commission on Population Movement (CMP), a since the beginning of the year working group within the Protection Cluster, with the aim of A survey conducted on IDPs in the south and in the north, revealed that 75% of displaced providing up-to-date data on internally displaced persons and households want to go back to their place of returnees as well as on host communities in Mali. origin, while 21% would like to stay in the The IOM teams as well as the ones from the National Directorate of place of displacement. Social Development (Direction Nationale du Développement Sociale- 283 935 returnees (to their places of origin) DNDS-in French) and from the General Directorate of Civil identified in Gao, Tombouctou, Kidal and Protection (Direction Générale de la Protection Civile-DGPC-in Mopti French) are deployed in all regions of Mali, whereas the DTM A survey conducted on IDPs’ primary needs, activities in Kidal are being carried out by the NGO Solidarités shows that 45% of the IDP households expressed needs in terms of food, 18% in the Internationales. -

FEWS Country Report MALI

Report Number 5 October 1986 FEWS Country Report MALI Afriua Bureau U.S. Agency for International Development MA p FEWS/PWA #5 MALI: Summary Map 1. Yelimane Cercle 2. Nioro Cercle 3. Nara Cercle Poor Rainiall. Grasshopper Damage Should Be Monitored 4. Goundtm Crcle Nutritional Stress Should Be Mobnitored 4 8 3 6 8. Menaka Cercle . __x/" /5 PoorGrasshopper Rainfall1 Damage Low Major River Levels Should Be Monitored 5. Bandia-gara Cercle 6. Douentza Cercie 7. Courma-Rharous Cercle Poor Rainfall Average to Better than Grasshoppei Damage Average Crops Nutritional Stress No Food Reserves Particular Arrondissements At -Risk Famine Early Warning System Country Report MALI Islands of Distress Prepared for the Africa Bureau of the U.S. Agency for International Deva'oprnent Prepared by Price, Williams & Associates, Inc. October 1986 Contents Page i Introduction 1 Summary 1 Rainfall and Vegetation 2 Map 2 4 Figure 1 - Satellite Vegetation Images 5 Agriculture 6 Tables 1, 2, 3 7 River Levels 8 Grasshoppers 9 Map 3 - Grasshoppers 10 Health and Nutrition 11 Market Conditions and Prices 11 Table 4 11 Population At-Risk 12 Map 4 - Populations At-Risk 13 Map 5 - Coincidence of At-Risk Factors INTRODUCTION This is the fifth of a series of monthly reports issued by the Famine Early Warning System (FEWS) on Mali. It is designed !o provide decisionmakers with current information anti analysis on existing and potential nutrition emergency situations. Each situatior identified is described in terms of geographical extent and the number of people involved, o- at-risk, and the proximate causes insofar a-3 they have been discerned. -

Mali PSR Quarterly Report Q1 FY2020

Mali Peacebuilding, Stabilization, and Reconciliation Quarterly Report – FY2020 October - December 2019 Implementation Period: April 16, 2018 - April 30, 2023 FY 2020 Quarterly Report October 1, 2019 - December 30, 2019 This document was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Creative Associates International, USAID's implementing partner under Mali PSR. USAID Point of Contact: Andrew Lucas, COR, [email protected] Prime Partner: Creative Associates International Activity Name: Mali Peacebuilding, Stabilization, and Reconciliation Contract #: 720-688-18-C-00002 CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................... 4 II. CONTEXT .......................................................................................................... 5 III. FOUNDATIONAL ACTIVITIES .................................................................... 9 IV. OBJECTIVE 1: RESILIENCE TO VIOLENCE AND CONFLICT REINFORCED ....................................................................................................... 11 V. OBJECTIVE 2: INCLUSIVE GOVERNANCE AND CIVIC ENGAGEMENT STRENGTHENED IN CONFLICT-AFFECTED COMMUNITIES ................. 16 VI. OBJECTIVE 3: EMPOWERING YOUTH AND BUILDING THEIR RESILIENCE TO VIOLENT EXTREMISM ........................................................ 16 VII. MONITORING AND EVALUATION ........................................................ 23 VIII. OPERATIONS ............................................................................................. -

FEWS Country Reports CHAD, MALI, NIGER and SUDAN

Report Number 19 Jarnuarly 1988 FEWS Country Reports CHAD, MALI, NIGER and SUDAN Africa Bureau U.S. Agency for International Development FANINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEM This is the nineteenth in a series of mont|-ly reports issued [y the Famine Early Warning System (FEWS). Niger and Sudan will be combined in one report Chad, Mali, designed until the crop cycle begins again in the Spring. to provide decisionrnakers with current information This report is emergency and analysis on existing and poteutial nutrition situations. Each bituation identified is described in terms of geographical extent and the number people involve,:, or at-risk, and the proximate of causes insofar as they have been discerred. Use of the term "at-risk" to identify vulneraLle populations is problematic tion exists. since no generally agreed upon defini- Yet, it i-,necessary to identify or "target" populations appropriate forms in-need or "at-risk" in order to determine and levels of intervention. Thus for the present, until a better usage can be found, FEWS reports will employ the term "at-risk' to mean.. • .those persons lacking sufficient food, or rescurc-s to acquire sufficient rood, to avert a nutritional crisis (i.e., a progressive deterioration in their health or nutritional condition below the status who, as a result, require specifc quo), and intervention to avoid a life-threatening situation. Perhaps of most import ance to decisionmakers, the FEWS effort highlights the process situation, hopefully witt, enough underlying the deteriorating specificity and forewarning to permit alternative examineil and implementeci. Food assistance intervention strategies to be strategies are key to famine avoidance. -

Appel Global Pour Le Mali 2012 Au 13 Juin 2012

APPEL GLOBAL MALI 2012 i Processus de Planification Humanitaire QUELQUES ORGANISATIONS PARTICIPANT AUX APPELS GLOBAUX CRS AARREC Humedica MENTOR CWS ACF IA MERLIN TGH DanChurchAid ACTED ILO Muslim Aid UMCOR DDG ADRA IMC NCA UNAIDS Diakonie Emerg. Aid Africare INTERMON NPA UNDP DRC AMI-France Internews NRC UNDSS EM-DH ARC INTERSOS OCHA UNEP FAO ASB OIM OHCHR UNESCO FAR ASI IPHD OXFAM UNFPA FHI AVSI IR PA UN-HABITAT FinnChurchAid CARE IRC PACT FSD CARITAS IRD PAI UNICEF GAA CEMIR International IRIN PAM UNIFEM GOAL CESVI IRW Plan UNJLC GTZ CFA Islamic Relief PMU-I UNMAS GVC CHF JOIN Première Urgence UNOPS Handicap International CHFI JRS RC/Germany UNRWA HCR CISV LWF RCO VIS HealthNet TPO CMA Malaria Consortium Samaritan's Purse WHO HELP CONCERN Malteser Save the Children World Concern HelpAge International COOPI Mercy Corps SECADEV World Relief HKI CORDAID MDA Solidarités WV Horn Relief COSV MdM SUDO ZOA HT MEDAIR TEARFUND ii Table des matières 1. RESUME ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Table I. Financement demandé et reçu par cluster/secteur ........................................................................ 6 Table II. Financement demandé et reçu par niveau de priorité ................................................................... 6 Table III. Financement demandé et reçu par agence .................................................................................... 7 2. CONTEXTE ET CONSÉQUENCES HUMANITAIRES ............................................................ -

Mali Peacebuilding, Stabilization, and Reconciliation

Mali Peacebuilding, Stabilization, and Reconciliation Quarterly Report – FY2020 April - June 2020 Implementation Period: April 16, 2018 - April 30, 2023 FY 2020 Quarterly Report April 1, 2020- June 30, 2020 This document was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Creative Associates International for the Mali Peacebuilding, Stabilization and Reconciliation project, contract number 720-688-18-C-00002. USAID Point of Contact: Andrew Greer, COR, [email protected] Prime Partner: Creative Associates International Activity Name: Mali Peacebuilding, Stabilization, and Reconciliation Contract #: 720-688-18-C-00002 CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................ 4 II. CONTEXT.................................................................................................................................. 5 IV. OBJECTIVE 1: RESILIENCE TO VIOLENCE AND CONFLICT REINFORCED ............. 10 V. OBJECTIVE 2: INCLUSIVE GOVERNANCE AND CIVIC ENGAGEMENT STRENGTHENED IN CONFLICT-AFFECTED COMMUNITIES ........................................... 17 VI. OBJECTIVE 3: EMPOWERING YOUTH AND BUILDING THEIR RESILIENCE TO VIOLENT EXTREMISM ............................................................................................................... 19 VII. MONITORING AND EVALUATION ................................................................................. 25 VIII. GRANTS .............................................................................................................................. -

Quarterly Report FY15

Rapid Education Risk Analysis in the Gao Region Report January 5, 2016 Table of Contents Table of Contents ....................................................................................................................... 1 Acknowledgments...................................................................................................................... 4 Tables ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Graphs ........................................................................................................................................ 7 Acronyms ................................................................................................................................... 8 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 9 SECTION I. CONTEXT AND JUSTIFICATION ............................................................................... 12 SECTION II. METHODOLOGY .................................................................................................... 13 II.1 Objectives of the RERA ...................................................................................... 13 II.2 Topics and Research Questions .......................................................................... 13 II.3 Analysis of Secondary Data ................................................................................ 14 II.4 Update of Secondary Data