Railroads, Factor Channelling and Increasing Returns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baltimore and Ohio Rail Road

Baltimore and Ohio Rail Road BALTIMORE AND OHIO RAIL ROAD. Spec. law of MD, February 28, 1827 Trackage, June 30, 1918: 2315.039 mi. First main track 774.892 mi. Second and other main tracks 1580.364 mi. Yard track and sidings Equipment Steam locomotives 2,242 Other locomotives 9 Freight cars 88,904 Passenger cars 1,243 Floating equipment 168 Work equipment 2,392 Miscellaneous 10 Equipment, leased Steam locomotives 16 to Baltimore and Ohio Chicago Terminal Steam locomotives 1 to Little Kanawha Railroad Steam locomotives 4 to Long Fork Railway Steam locomotives 1 to Morgantown and Kingwood Steam locomotives 5 to The Sandy Valley & Elkhorn Railway Steam locomotives 6 to The Sharpsville Railroad Steam locomotives 30 to Staten Island Rapid Transit Steam locomotives 158 from Toledo and Cincinnati Freight cars 4 to Long Fork Railway Freight cars 5 to The Sandy Valley & Elkhorn Railway Freight cars 5,732 from Toledo and Cincinnati Freight cars 976 from Mather Humane Stock Transportation Co. Passenger cars 1 to Baltimore and Ohio Chicago Terminal Passenger cars 3 to Long Fork Railway Passenger cars 4 to The Sandy Valley & Elkhorn Railway Passenger cars 1 to The Sharpsville Railroad Passenger cars 110 from Toledo and Cincinnati Work equipment 2 to The Sandy Valley & Elkhorn Railway Work equipment 57 to Staten Island Rapid Transit Miscellaneous 2 from Toledo and Cincinnati Miscellaneous 1 from Baltimore and Ohio in Pennsylvania Miscellaneous 7 from Baltimore and Ohio Southwestern The Baltimore and Ohio Rail Road controls the following companies: -

CP's North American Rail

2020_CP_NetworkMap_Large_Front_1.6_Final_LowRes.pdf 1 6/5/2020 8:24:47 AM 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Lake CP Railway Mileage Between Cities Rail Industry Index Legend Athabasca AGR Alabama & Gulf Coast Railway ETR Essex Terminal Railway MNRR Minnesota Commercial Railway TCWR Twin Cities & Western Railroad CP Average scale y y y a AMTK Amtrak EXO EXO MRL Montana Rail Link Inc TPLC Toronto Port Lands Company t t y i i er e C on C r v APD Albany Port Railroad FEC Florida East Coast Railway NBR Northern & Bergen Railroad TPW Toledo, Peoria & Western Railway t oon y o ork éal t y t r 0 100 200 300 km r er Y a n t APM Montreal Port Authority FLR Fife Lake Railway NBSR New Brunswick Southern Railway TRR Torch River Rail CP trackage, haulage and commercial rights oit ago r k tland c ding on xico w r r r uébec innipeg Fort Nelson é APNC Appanoose County Community Railroad FMR Forty Mile Railroad NCR Nipissing Central Railway UP Union Pacic e ansas hi alga ancou egina as o dmon hunder B o o Q Det E F K M Minneapolis Mon Mont N Alba Buffalo C C P R Saint John S T T V W APR Alberta Prairie Railway Excursions GEXR Goderich-Exeter Railway NECR New England Central Railroad VAEX Vale Railway CP principal shortline connections Albany 689 2622 1092 792 2636 2702 1574 3518 1517 2965 234 147 3528 412 2150 691 2272 1373 552 3253 1792 BCR The British Columbia Railway Company GFR Grand Forks Railway NJT New Jersey Transit Rail Operations VIA Via Rail A BCRY Barrie-Collingwood Railway GJR Guelph Junction Railway NLR Northern Light Rail VTR -

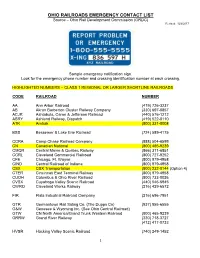

OHIO RAILROADS EMERGENCY CONTACT LIST Source – Ohio Rail Development Commission (ORDC) Revised: 12/6/2017

OHIO RAILROADS EMERGENCY CONTACT LIST Source – Ohio Rail Development Commission (ORDC) Revised: 12/6/2017 Sample emergency notification sign. Look for the emergency phone number and crossing identification number at each crossing. HIGHLIGHTED NUMBERS – CLASS 1 REGIONAL OR LARGER SHORTLINE RAILROADS CODE RAILROAD NUMBER AA Ann Arbor Railroad (419) 726-3237 AB Akron Barberton Cluster Railway Company (330) 697-0857 ACJR Ashtabula, Caron & Jefferson Railroad (440) 576-1212 ASRY Ashland Railway, Dispatch (419) 522-0110 ATK Amtrak (800) 331-0008 BSS Bessemer & Lake Erie Railroad (724) 589-4175 CCRA Camp Chase Railroad Company (888) 504-6599 CN Canadian National (800) 465-9239 CMQR Central Maine & Quebec Railway (866) 311-6851 CCRL Cleveland Commercial Railroad (800) 727-9252 CFE Chicago, Ft. Wayne (800) 979-4958 CIND Central Railroad of Indiana (800) 979-4958 CSX CSX Transportation (800) 232-0144 (Option 4) CTER Cincinnati East Terminal Railway (800) 979-4958 CUOH Columbus & Ohio River Railroad (800) 733-0026 CVSX Cuyahoga Valley Scenic Railroad (440) 546-5945 CWRO Cleveland Works Railway (216) 429-6572 FIR Flats Industrial Railroad Company (216) 696-7951 GTR Germantown Rail Siding Co. (The Dupps Co) (937) 855-6555 G&W Genesee & Wyoming Inc. (See Ohio Central Railroad) GTW CN North America/Grand Trunk Western Railroad (800) 465-9239 GRRW Grand River Railway (330) 718-3727 (412) 417-0733 HVSR Hocking Valley Scenic Railroad (740) 249-1452 1 CODE RAILROAD NUMBER IE Indiana Eastern Railroad (877) 788-0629 IN Indiana Northeastern Railway Company (517) 398-0005 (517) 278-4614 INOH Indiana & Ohio Railroad (800) 979-4958 IOCR Indiana & Ohio Central Railroad (800) 979-4958 IORY Indiana & Ohio Railway (800) 979-4958 MVRY Mahoning Valley Railway (800) 733-0026 ND&W Napoleon, Defiance & Western (479) 414 6563 MRTA Akron Metro RTA (330) 612-3016 (330) 957-0157 NSS Newburgh & South Shore Railroad (844) 564-8091 NOW Northern Ohio & Western Railway (844) 562-8091 NS Norfolk Southern Corporation (800) 453-2530 NTRY Republic N&T Railroad (330) 438-5466 OHCR Ohio Central Railroad, Inc. -

Michigan's Railroad History

Contributing Organizations The Michigan Department of Transportation (MDOT) wishes to thank the many railroad historical organizations and individuals who contributed to the development of this document, which will update continually. Ann Arbor Railroad Technical and Historical Association Blue Water Michigan Chapter-National Railway Historical Society Detroit People Mover Detroit Public Library Grand Trunk Western Historical Society HistoricDetroit.org Huron Valley Railroad Historical Society Lansing Model Railroad Club Michigan Roundtable, The Lexington Group in Transportation History Michigan Association of Railroad Passengers Michigan Railroads Association Peaker Services, Inc. - Brighton, Michigan Michigan Railroad History Museum - Durand, Michigan The Michigan Railroad Club The Michigan State Trust for Railroad Preservation The Southern Michigan Railroad Society S O October 13, 2014 Dear Michigan Residents: For more than 180 years, Michigan’s railroads have played a major role in the economic development of the state. This document highlights many important events that have occurred in the evolution of railroad transportation in Michigan. This document was originally published to help celebrate Michigan’s 150th birthday in 1987. A number of organizations and individuals contributed to its development at that time. The document has continued to be used by many since that time, so a decision was made to bring it up to date and keep the information current. Consequently, some 28 years later, the Michigan Department of Transportation (MDOT) has updated the original document and is placing it on our website for all to access. As you journey through this history of railroading in Michigan, may you find the experience both entertaining and beneficial. MDOT is certainly proud of Michigan’s railroad heritage. -

North Carolina Railroad System Map-August 2019

North Carolina !( Railroad System Clover !( !( South Boston Franklin Danville !( !( !( Mount Airy !( !( Clarksville Alleghany Eden !( Mayo Currituck Camden Ashe Hyco !( !( Gates !( Roanoke !( Conway Surry YVR Norlina Weldon R Stokes Rockingham Granville Rapids Elizabeth CA Caswell Person Vance !( Hertford City !( Roxboro Northampton !( Reidsville !( !( YVRR Oxford Henderson Warren Halifax !(Ahoskie VA Rural NC Watauga Wilkes !( Pasquotank Hall CA !( !( Erwin!( Yadkin Orange Kelford Chowan Perquimans North Durham Guilford !( N Franklin Avery Wilkesboro Forsyth !( Burlington Butner !( CDOT Mitchell ! Bertie !( Winston ! !(Hillsborough Franklinton Edenton Salem Greensboro Nash Caldwell ! Durham Rocky Midway !( High !( Wake Forest CLNA !(Taylorsville Iredell Davie ! Alamance !( ! Mount Yancey Lenoir Davidson Spring ! Madison !( Point Carrboro !( !( Tarboro Washington Alexander A Wake Burke C R Hope !( W C C T Zebulon Plymouth Tyrrell Y O !( Edgecombe !( Statesville !( D Cary CLNA Middlesex Lexington C !( !( !( Parmele Dare N ! W ! W Martin s Buncombe !( Hickory ! S !( S ain Chatham Raleigh Wendell t S n McDowell !( Morganton S !(Apex ! ou CMLX Marion !( k !Wilson M c rk Asheboro NHVX ky a Haywood !( !( o Pitt o P T Newton ! A l Salisbury n !( Wilson f m a O New Hll l !(Clayton N S n Old Fort Catawba !( L CLNA D t o m i CMIZ Denton u a t !( CLNA C C Greenville re a BLU Rowan Randolph u !( N Asheville G G N C !( W !( !( Belhaven Swain !( S !( Fuquay-Varina !( S !( Waynesville BLU A ! Washington !( GSM Lincoln Lincolnton ! T Selma Chocowinity -

Railamerica, Inc

RailAmerica, Inc. Dawn of a New Era in Railroading RailAmerica Corporate Video on CD RailAmerica, Inc. 5300 Broken Sound Boulevard NW 2000 Annual Report Boca Raton, Florida 33487 (561) 994-6015 www.railamerica.com CORPORATE HEADQUARTERS 5300 Broken Sound Boulevard NW Boca Raton, Florida 33487 (561) 994-6015 CORPORATE OFFICES (561) 994-4629 (facsimile) Corporate Headquarters Boca Raton, Florida Regional Office San Antonio, Texas REGISTRAR AND TRANSFER AGENT Regional Office San Francisco, California American Stock Transfer and Trust Company NORTH AMERICAN RAILROADS New York, New York Cape Breton & Central Nova Scotia Railway Stellarton, Nova Scotia, Canada (800) 937-5449 Carolina Piedmont Railroad Laurens, South Carolina Cascade & Columbia River Railroad Omak, Washington ANNUAL MEETING OF SHAREHOLDERS Central Oregon & Pacific Railroad Roseburg, Oregon RailAmerica, Inc. June 22, 2001 at 10 a.m. EDT Central Railroad Company of Indiana Cincinnati, Ohio Boca Raton Marriott Hotel Central Railroad Company of Indianapolis Kokomo, Indiana (www.railamerica.com), 5150 Town Center Circle Central Western Railway Stettler, Alberta, Canada Boca Raton, Florida Chesapeake & Albemarle Railroad Elizabeth City, North Carolina the world’s largest short Connecticut Southern Railroad East Hartford, Connecticut line and regional rail- INVESTOR INQUIRIES Dakota Rail Hutchinson, Minnesota To receive copies of reports filed with the Dallas, Garland & Northeastern Railroad Garland, Texas road operator, owns 39 Securities and Exchange Commission or Esquimalt & Nanaimo Railway Nanaimo, Vancouver Island, Company Profile short line and regional other information about RailAmerica, contact British Columbia, Canada Wayne A. August, Assistant Vice President of Georgia Southwestern Railroad Smithville, Georgia railroads operating over Investor Relations, at the corporate offices, Goderich-Exeter Railway Kitchener, Ontario, Canada or email at [email protected]. -

Rooted in History. Moving Successfully Into the Future

CLEVELAND, OHIO OHIO RIVER VALLEY PITTSBURGH, PENNSYLVANIA AKRON, OHIO BPRR 20 WEIRTON 80 CN 3 90 43 2 22 8 480 MANTUA 22 42 BROOKE ALLISON 76 NEW 71 77 376 PARK 80 28 KENSINGTON EUCLID WINTERSVILLE HUDSON PENNSYLVANIA WEST VIRGINIA 8 80 79 303 RICHFIELD 303 STEUBENVILLE 19 BRUNSWICK 303 91 BEAVER ARM- STREETSBORO AVR 43 2 CUOH COLLINWOOD 22 LAKE FOLLANSBEE 44 AVR YARD CVSR 279 OAKMONT 3 90 POHC 91 14 88 WTRM E GEAUGA MINGO JCT. MOON ETNA 271 SHARPSBURG PENN HILLS I 20 7 CLINTON ALLEGHENY 28 N. BESSEMER 8 C U AB Y A R 271 151 AVR STOW MCKEES H RAVENNA 151 76 O 59 ROCKS ISLAND G E 376 A 59 AVENUE AVR 8 YARD R SMITHFIELD MEDINA IV CUYAHOGA (NS Trackage Rights) (NS Trackage 30 ER KENT E 18 18 FALLS BRILLIANT FAIRLAWN K (NS Trackage Rights) 322 L A 322 79 PITTSBURGH 6 261 2 CLEVELAND 22 (AB) HEIGHTS GATES 152 67 88 71 6 MILLS 376 22 ROOK 30 94 76 CHB URR ADENA JEFFERSON SHANNON AKRON TALLMADGE URR BRIMFIELD BETHANY COPLEY 77 6 CLEVELAND RUN POHC 3 BRITTAIN 44 76 SHARON (AB) 91 GLENWOOD CENTER 21 59 YARD FIR OAKDALE EDGAR YARD (AB) 43 CWRO RAYLAND DILLONVALE THOMSON DUQUESNE BRENTWOOD WORKS (AB) 19 57 MOGADORE CCRL 90 URR TILTONSVILLE AVR 8 PENNSYLVANIA 90 CWRO 250 WEST VIRGINIA CWRO 422 OHIO WEST LIBERTY BRIDGEVILLE CWRO MCDONALD 76 224 KNOB CAMPBELL LONGVIEW 76 224 224 20 URR WADSWORTH AB ROAD ARCELOR NORTON 83 MITTAL YORKVILLE MCKEESPORT YARD CWRO STEEL BELMONT MIFFLIN JCT. -

Abandoned Railroad Inventory and Policy Plan Abandoned Railroad Inventory and Policy Plan

ABANDONED RAILROAD INVENTORY AND POLICY PLAN ABANDONED RAILROAD INVENTORY AND POLICY PLAN prepared by: Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission The Bourse Building 111 S. Independence Mall East Philadelphia, PA 19106-2515 September 1997 This report was printed on recycled paper The preparation of this report was funded through federal grants from the U.S. Department of Transportation's Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and Federal Transit Administration (FTA) , as well as by DVRPC's member governments. The authors, however, are solely responsible for its findings and conclusions, which may not represent the official views or policies of the funding agencies. Created in 1965, the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission (DVRPC) is an interstate, intercounty and intercity agency which provides continuing, comprehensive and coordinated planning for the orderly growth and development of the Delaware Valley region. The region includes Bucks, Chester, Delaware, and Montgomery counties as well as the City of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania and Burlington, Camden, Gloucester, and Mercer counties in New Jersey. The Commission is an advisory agency which divides its planning and service functions between the Office of the Executive Director, the Office of Public Affairs, and three line Divisions: Transportation Planning, Regional Planning, and Administration. DVRPC's mission for the 1990s is to emphasize technical assistance and services and to conduct high priority studies for member state and local governments, while determining and meeting the needs of the private sector. The DVRPC logo is adapted from the official seal of the Commission and is designed as a stylized image of the Delaware Valley. The outer ring symbolizes the region as a whole while the diagonal bar signifies the Delaware River flowing through it. -

The Hocking Valley Railway, Ended Its Receivership in After Only Two Years, Exemplifying the Basic Soundness of Most Midwestern and Ohio Carriers

HISTORICAL INTRODUCTION AS THE RAILWAY AGE developed, Ohio provided a perfect environment for the railroad promoter. By the mid-nineteenth century the state benefited from a growing and industrious population; boasted a large number of ex- panding towns and cities; claimed a plethora of booming and prosperous farms, businesses, mines, and factories; and possessed farseeing, risk-taking en- trepreneurs who effectively tapped pools of investment capital. Even the terrain was mostly attractive, posing no major construction obstacles. When the final boom in railroad construction ended in the five-year misery known as the Panic of , ribbons of rail laced Ohio, providing most localities with “the oxygen of life.” After hard times lifted, modest construction continued; in the Ohio rail network peaked with , route miles. Residents of all counties enjoyed access to the iron horse. In fact, it was not unusual for a community to have two or more carriers. The evolution of the Ohio railway network mirrored what occurred in other settled sections. The earliest carriers were primitive affairs, best repre- sented by the Mad River and Lake Erie Rail Road that in opened be- tween Sandusky and Bellevue, a distance of miles. These short lines typically connected bodies of water with inland areas. Later, longer roads appeared, often absorbing these pioneer pikes. Then, following the Civil War, system building gained momentum. Once the national economy recovered from the hard times of the mid-s, capitalists fused together various carriers, usually by direct purchase or through long-term lease. These financial deals created regional and interregional networks. In , Jay Gould, arguably the most talented and aggressive railroad financier of the Gilded Age, took charge of the future Wabash Railroad and used the Toledo, Wabash, and Western Rail- way that stretched between Toledo and St. -

View Detailed

Detroit WASHTENAW CHAUTAU East JACKSON WAYNE Erie Salamanca MICHIGAN FlatFlat RockRock N C S CSXT WNYP LENAWEE N NS DiannDiann ERIE NS CorryCorry Warren SXT Bradford MONROEC CN AA WNYP Chicago L E PetersburgPetersburg CSXT Mt. Jewett Lake Erie CRAWFORD C Blue Island SXT FULTON LUCAS LAKE ASHTABULA ToledoToledo NS NS Tolleston Delta NS NS Valparaiso CSX OTTAWA St. Ridgway OCTL WNYP Marys T Cleveland GEAUGA IORY NS TRUMBULL NDW CSXT SANDUSKY ERIE MERCER VENAGO Driftwood N NS Hamlet WOOD CUYAHOGA NS HENRY CSXT OW XT WTRM CS LORAIN NS CN Columbia PORTAGE Warsaw CSXT WarrenWarren City HamlerHamler WE SUMMIT Brookville SENECA MEDINA RavennaRavenna YB PENNSYLVANIA CSXT CSXT HURON WE BUTLER CLARIO NS YARR DuBois Ft Wayne LeipsicLeipsic YoungstownYoungstown NewNew CastleCastle PetroliaPetrolia Ottawa NS LAWRENCE CSXT WE MAHONING Punxsutawney PUTNAM HANCOCK WarwickWarwick WE BPRR UpperUpper WE Delphos NS CRAWFORD ASRY MVRY SanduskySandusky WAYNE CanalCanal FultonFulton NS NS ButlerButler FordFord ParkPark NS Decatur ASHLAND NS/CSXT CrestlineCrestline MassillonMassillon OHCROHCR STARK EvansEvans ARMST CFE Bayard YSE RJCW Lima WYANDOT BEAVER CityCity BrewsterBrewster HarmonHarmon COLUMBIANA CN ALLEN HARDIN NS CSXT RICHLAND BeachBeach CityCity Minerva FreeportFreeport CSXT NS UniopolisUniopolis CSXT NS Jct WE AOR HOLMES DundeeDundee AliquippaAliquippa ALLEGHENY AUGLAIZE WE AllisonAllison ParkPark Marion OHIO BarrsBarrs MMillsills CARROLL CSXT MORROW MARION KNOX JEFFERSONNorthNorth NS Kokomo SugarcreekSugarcreek NevilleNeville IslandIsland JacksonJackson CenterCenter RJCL ApexApex UNION TUSCARAWAS ScioScio McKeesMcKees RocksRocks Homer City LOGAN CSXT Mt.Mt. VernonVernon BalticBaltic NS Hartford QuincyQuincy BellefontaineBellefontaine COSHOCTON PearlPearl CSXT DennisonDennison GouldsGoulds PittsburghPittsburgh City FresnoFresno DELAWARE MorganMorgan RunRun POHC HARRISON NS WestWest LLibertyiberty Hopedale WE NS W SHELBY CoshoctonCoshocton MingoMingo C NewcomerstownNewcomerstown WE CHAMPAIGN S CSXT MOR X ArdenArden T CUOH Jct.Jct. -

The Columbus and Hocking Valley Railroad

The Columbus and Hocking Valley Railroad BEFORE GREENE COULD complete any arrangements, the whole coun- try plunged into sharper controversy over the slavery issue, and finally into open conflict. (Greene and his business partner E. H. Moore would serve on the Athens Military Committee for the duration.) During the Civil War, prices rose at a furious rate. The subject of railroad construction was widely discussed in the press due to the exorbitant cost of coal and the difficulty of transporting it in sufficient quantities by canal boat. There was very little advancement in the Hocking Hills during the war years, but Greene did find four other men who saw something of the same vi- sion that beckoned him. Toward the end of the war, they decided to form a business venture. The incorporation papers of many railroads of the period indicate intentions to lay rails to more destinations than were actually con- structed, and theirs was no exception. Remembering Latrobe’s survey of , Greene and his partners decided to expand upon Greene’s original plans. William P. Cutler, John Mills, Douglas Putnam, Eliakim Hastings Moore, and Milbury Miller Greene appeared before the Ohio secretary of state on April , , to incorporate their railroad. The certificate stated: We, the undersigned, do hereby certify that we have associated ourselves into a company under the name of the Mineral Railroad Company for the 12 The Columbus and Hocking Valley Railroad 13 purpose of constructing a railroad from Athens in Athens County, thence running through the Counties of Athens, Hocking, Fairfield and Franklin to the City of Columbus in said Franklin County, all in the State of Ohio, and with a capital stock of one million five hundred thousand dollars ($,,).1 Five days after the incorporation, Greene employed an engineer to make a survey of the proposed route. -

Chapter 7. Railroads and Trolley Lines —Unraveling the Mystery of Sheffield’S Rail Transportation

CHAPTER 7. RAILROADS & TROLLEY LINES CHAPTER 7. RAILROADS AND TROLLEY LINES —UNRAVELING THE MYSTERY OF SHEFFIELD’S RAIL TRANSPORTATION First of all, what is rail transportation? Simply, it is the conveyance of goods and passengers by means of wheeled vehicles running on rails. Secondly, what is the mystery or perhaps puzzle? This is where the answer gets a little more complicated. The history of rail transportation in Sheffield, and more broadly Lorain County, is a somewhat bewildering array of name changes as one rail line company purchased another or several rail lines merged to form a new line, resulting in as many as eight different names for the same set of tracks. Then too, the mode of propulsion varied from horse-drawn cars, to steam locomotives, to electric trolleys, and to diesel engines, adding another degree of complexity. The following is an attempt to chronologically sort all of this out and describe the history of rail transportation in Sheffield and its environs. Nickel Plate Road double tracks in Sheffield Lake, Ohio; view toward the west, circa 1950 (Dennis Lamont). reporting mark. These marks are an alphabetic code of one to five letters used to identify owners or lessees of rolling stock. In North America, the marks are stenciled on each piece of equipment, Lake Shore Electric Railway interurban trolley loading passengers at along with a one- to six-digit number, which together uniquely Cleveland Public Square en route to Lorain, 1935 (Albert C. Doane). identify all rail cars and locomotives. This allows rolling stock Some basic definitions may help in this process.