Scanned Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Super Chief – El Capitan See Page 4 for Details

AUGUST- lyerlyer SEPTEMBER 2020 Ready for Boarding! Late 1960s Combined Super Chief – El Capitan see page 4 for details FLYER SALE ENDS 9-30-20 Find a Hobby Shop Near You! Visit walthers.com or call 1-800-487-2467 WELCOME CONTENTS Chill out with cool new products, great deals and WalthersProto Super Chief/El Capitan Pages 4-7 Rolling Along & everything you need for summer projects in this issue! Walthers Flyer First Products Pages 8-10 With two great trains in one, reserve your Late 1960s New from Walthers Pages 11-17 Going Strong! combined Super Chief/El Capitan today! Our next HO National Model Railroad Build-Off Pages 18 & 19 Railroads have a long-standing tradition of getting every last WalthersProto® name train features an authentic mix of mile out of their rolling stock and engines. While railfans of Santa Fe Hi-Level and conventional cars - including a New From Our Partners Pages 20 & 21 the 1960s were looking for the newest second-generation brand-new model, new F7s and more! Perfect for The Bargain Depot Pages 22 & 23 diesels and admiring ever-bigger, more specialized freight operation or collection, complete details start on page 4. Walthers 2021 Reference Book Page 24 cars, a lot of older equipment kept rolling right along. A feature of lumber traffic from the 1960s to early 2000s, HO Scale Pages 25-33, 36-51 Work-a-day locals and wayfreights were no less colorful, the next run of WalthersProto 56' Thrall All-Door Boxcars N Scale Pages 52-57 with a mix of earlier engines and equipment that had are loaded with detail! Check out these layout-ready HO recently been repainted and rebuilt. -

The Odyssey of Five Locomotives: 1835-1965 Benjamin F

The Odyssey of Five Locomotives: 1835-1965 Benjamin F. G. Kline, Jr. On October 21, 1864, this item appeared in the Lancaster newspaper: "The locomotive works, operated by J. A. Norris, has been contracted for delivery of five locomotives to the Western Pacific Railroad in California." Let us examine this for more detail. First, the Western Pacific Rail- road — chartered December 13, 1862 — in November 1869, was consoli- dated with the San Francisco Bay Railroad, which was chartered Septem- ber 25, 1868. Following this consolidation, it retained the name of the Western Pacific Railroad until June 23, 1870, when it was in turn consol- idated with the Central Pacific Railroad of California. The consolidated line became a part of the Central Pacific Railroad of California. The Western Pacific Railroad and the San Francisco Bay Railroad linked Sacramento with Oakland and the San Francisco area. This provided the Central Pacific with a connection to the San Francisco area. The original Western Pacific was a line 123.45 miles in length; the consolidation with the San Francisco Bay Railroad Company added about 22.5 miles to this, giving the consolidated Western Pacific Railroad a total mileage of approximately 146 miles. A sheet issued November 6, 1868 listed all Central Pacific motive power with their specifications. Also listed separately were the ten locomo- tives which were received from the Western Pacific Railroad. The first five are of no interest to us because they were Baldwin and Mason pro- ducts. The remaining five were listed as being built by Norris of Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Second, let us look at the builder. -

Department of Transportation

Vol. 76 Friday, No. 156 August 12, 2011 Part III Department of Transportation Federal Railroad Administration 49 CFR Part 228 Hours of Service of Railroad Employees; Substantive Regulations for Train Employees Providing Commuter and Intercity Rail Passenger Transportation; Conforming Amendments to Recordkeeping Requirements; Final Rule VerDate Mar<15>2010 17:08 Aug 11, 2011 Jkt 223001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4717 Sfmt 4717 E:\FR\FM\12AUR2.SGM 12AUR2 mstockstill on DSK4VPTVN1PROD with RULES2 50360 Federal Register / Vol. 76, No. 156 / Friday, August 12, 2011 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION • Hand Delivery: Room W12–140 on C. Significant Task Force Contributions to the Ground level of the West Building, the Development of the NPRM Federal Railroad Administration 1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE., 1. Schedule Analysis Washington, DC, between 9 a.m. and 2. Fatigue Mitigation Tool Box 49 CFR Part 228 D. Areas of Working Group and Task Force 5 p.m. Monday through Friday, except Concern During Development of the Federal holidays. NPRM [Docket No. FRA–2009–0043, Notice No. 2] Instructions: All submissions must 1. Proposed Definitions of ‘‘Type 1 include the agency name and docket Assignment’’ and ‘‘Type 2 Assignment’’ RIN 2130–AC15 number or Regulatory Identification 2. Proposed Limitations on Number of Hours of Service of Railroad Number (RIN) for this rulemaking. Note Consecutive Days that all petitions received will be posted 3. Precision of Fatigue Models and Employees; Substantive Regulations Threshold for Train Employees Providing without change to http:// www.regulations.gov including any 4. Freight Railroad Employees Acting as Commuter and Intercity Rail Passenger Pilots for Commuter or Intercity Transportation; Conforming personal information. -

Baltimore and Ohio Rail Road

Baltimore and Ohio Rail Road BALTIMORE AND OHIO RAIL ROAD. Spec. law of MD, February 28, 1827 Trackage, June 30, 1918: 2315.039 mi. First main track 774.892 mi. Second and other main tracks 1580.364 mi. Yard track and sidings Equipment Steam locomotives 2,242 Other locomotives 9 Freight cars 88,904 Passenger cars 1,243 Floating equipment 168 Work equipment 2,392 Miscellaneous 10 Equipment, leased Steam locomotives 16 to Baltimore and Ohio Chicago Terminal Steam locomotives 1 to Little Kanawha Railroad Steam locomotives 4 to Long Fork Railway Steam locomotives 1 to Morgantown and Kingwood Steam locomotives 5 to The Sandy Valley & Elkhorn Railway Steam locomotives 6 to The Sharpsville Railroad Steam locomotives 30 to Staten Island Rapid Transit Steam locomotives 158 from Toledo and Cincinnati Freight cars 4 to Long Fork Railway Freight cars 5 to The Sandy Valley & Elkhorn Railway Freight cars 5,732 from Toledo and Cincinnati Freight cars 976 from Mather Humane Stock Transportation Co. Passenger cars 1 to Baltimore and Ohio Chicago Terminal Passenger cars 3 to Long Fork Railway Passenger cars 4 to The Sandy Valley & Elkhorn Railway Passenger cars 1 to The Sharpsville Railroad Passenger cars 110 from Toledo and Cincinnati Work equipment 2 to The Sandy Valley & Elkhorn Railway Work equipment 57 to Staten Island Rapid Transit Miscellaneous 2 from Toledo and Cincinnati Miscellaneous 1 from Baltimore and Ohio in Pennsylvania Miscellaneous 7 from Baltimore and Ohio Southwestern The Baltimore and Ohio Rail Road controls the following companies: -

California State Rail Plan 2005-06 to 2015-16

California State Rail Plan 2005-06 to 2015-16 December 2005 California Department of Transportation ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER, Governor SUNNE WRIGHT McPEAK, Secretary Business, Transportation and Housing Agency WILL KEMPTON, Director California Department of Transportation JOSEPH TAVAGLIONE, Chair STATE OF CALIFORNIA ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER JEREMIAH F. HALLISEY, Vice Chair GOVERNOR BOB BALGENORTH MARIAN BERGESON JOHN CHALKER JAMES C. GHIELMETTI ALLEN M. LAWRENCE R. K. LINDSEY ESTEBAN E. TORRES SENATOR TOM TORLAKSON, Ex Officio ASSEMBLYMEMBER JENNY OROPEZA, Ex Officio JOHN BARNA, Executive Director CALIFORNIA TRANSPORTATION COMMISSION 1120 N STREET, MS-52 P. 0 . BOX 942873 SACRAMENTO, 94273-0001 FAX(916)653-2134 (916) 654-4245 http://www.catc.ca.gov December 29, 2005 Honorable Alan Lowenthal, Chairman Senate Transportation and Housing Committee State Capitol, Room 2209 Sacramento, CA 95814 Honorable Jenny Oropeza, Chair Assembly Transportation Committee 1020 N Street, Room 112 Sacramento, CA 95814 Dear: Senator Lowenthal Assembly Member Oropeza: On behalf of the California Transportation Commission, I am transmitting to the Legislature the 10-year California State Rail Plan for FY 2005-06 through FY 2015-16 by the Department of Transportation (Caltrans) with the Commission's resolution (#G-05-11) giving advice and consent, as required by Section 14036 of the Government Code. The ten-year plan provides Caltrans' vision for intercity rail service. Caltrans'l0-year plan goals are to provide intercity rail as an alternative mode of transportation, promote congestion relief, improve air quality, better fuel efficiency, and improved land use practices. This year's Plan includes: standards for meeting those goals; sets priorities for increased revenues, increased capacity, reduced running times; and cost effectiveness. -

Nathaniel C. Guest, Esq., Vice President

N A T H A N I E L C. G U E S T, E S Q . __________________________________ 1682 Farmington Avenue ▪ Pottstown, Pennsylvania 19464 ▪ 610.724.9611 Email: [email protected] or [email protected] EDUCATION Cornell University, College of Architecture, Art, and Planning, Ithaca, New York. Department of City and Regional Planning. Masters of Historic Preservation Planning Cornell Real Estate Journal, Staff Editor. Planned and Coordinated visit by internationally-renowned preservation leader Arthur Ziegler. Graduate Teaching and Research Assistant for Richard Booth, Esq., and Dr. Michael Tomlan. Co-taught class Economics and Financing of Neighborhood Conservation and Preservation. Temple University School of Law, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Juris Doctorate, cum laude, Integrated Program in Transactional Law. Temple Political and Civil Rights Law Review, Staff Member; Selected as Articles Editor, 2008-2009. Burton Award for Legal Achievement: Comment Putting History on a Stone Foundation: Toward Legal Rights for Historic Property published by Temple in 2009; Selected as Temple’s 2009 submission for the Burton Award For Legal Achievement, a national law article competition; Awarded the Burton Award by Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, June 14, 2010, at the Library of Congress. Albert H. Friedman Prize for Legal Writing. Pennsylvania Bar, Admitted October 2010. Cornell University, College of Arts and Sciences, Ithaca, New York. Bachelor of Arts in American Material Culture, an Independent Major, magna cum laude with Distinction in All Subjects. Senior Honors Thesis: Sentimental Journey: The Entropy of Progress Through the Depiction of American Railroads in Art. Phi Beta Kappa and Phi Kappa Phi National Honor Fraternities. Dean’s List Scholar. -

National Board BULLETIN -- Winter 2002

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– FEATURES BULLETIN 6 Making Your Way Through Combustion Systems — WINTER 2002 • VOLUME 57 • NUMBER 1 By Lee Richardson Donald E. Tanner 10 The California State Railroad Museum: On Track to Executive Director Preserve an American Legacy Richard L. Allison Assistant Executive Director – Administrative Robert P. Sullivan 20 Welcome to Colorado Springs and the 71st General Assistant Executive Director – Technical Meeting Paul D. Brennan, APR Director of Communications Joan M. Webster 34 Why Boilers Fail — By Rita M. DeHart, P.E. Staff Services Manager Valerie T. Sterling Publications Editor Kimberly A. Miller ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– DEPARTMENTS Publications Coordinator BOARD OF TRUSTEES 2 Executive Director’s Message: Safety by Design, Not by Default David A. Douin Chairman Robert Reetz 3 Regulatory Review: Membership Survey: Regulations of Antique/ First Vice Chairman Historical/Hobby Boilers Vary by Jurisdiction Mark Mooney Second Vice Chairman 8 Inspector’s Insight: Donald E. Tanner Venting of Combustion Equipment Secretary-Treasurer Yash Nagpaul 32 Have You Met . ? Yash Nagpaul, Manager/Chief Boiler Member at Large Inspector, State of Hawaii Richard D. Mile Member at Large Malcolm J. Wheel 40 People: Withers Joins National Board Staff, New Members Elected in Member at Large New Hampshire and Oregon, Bynog to Chair NBIC Committee, Lee Doran Robert R. Cate Retires from the National Board, Mooney Elected to Board of Trustees; Past Chairman Calling All Honorary Members ADVISORY COMMITTEE 43 Training Matters: Safety by Association Stephen Rudnickas Representing authorized inspection agencies (insurance companies) 44 Training Calendar Russell I. Mullican Representing National Board stamp holders Dr. W. D’Orville Doty Representing the welding industry ON THE COVER: Dr. -

It's a Great Time to Be in the Railroad Business, but If You're a Short Line That's Going to Make It, You've Got to Lear

SHORT TAKES Caddo Valley Railroad Co. Headquarters: Glenwood, Ark. Route: 52.9 miles from Gurdon to Bird Mill, Ark. Interchange: Gurdon, with UP PREX GP16 1610 cuts through the piney woods near Gurdon, Ark. It’s a great time to be in the railroad business, but if you’re a short line that’s going to make it, you’ve got to learn how to add big-time value by Roy Blanchard riters such as Archie Robertson, Lucius road, or about 30 percent of the U.S. rail sys- Beebe, and William S. Young prepared us tem. They handle more than 12 million revenue Wfor short lines of an unhurried nature. Far units a year.* from the hustle and bustle of big-city commerce, Of the short lines operating today, 16 are these railroads went about their business in a lei- owned by Class I railroads, and they fall into two surely way. Robertson captured such lines in categories: switching and terminal railroads, and 1945’s Slow Train to Yesterday; Beebe immortal- actual short lines like the Winston-Salem South- ized them in his 1947 classic Mixed Train Daily; bound (a joint property of Norfolk Southern and and Young kept TRAINS readers informed about CSX, and a holdover from joint control of Norfolk the little roads well into the 1950s with his & Western and Atlantic Coast Line) or the Texas monthly column, “Short Lines.” Mexican (Kansas City Southern). The three best The 1980 Staggers Act [page 10], the subse- known are probably the Belt Railway of Chicago quent deregulation of railroad rates, and Wall (owned by six Class Is), probably the biggest Street have combined to end all that. -

ERTAC Rail Emissions Inventory Part 3: Class II and III Locomotives

ERTAC Rail Emissions Inventory Part 3: Class II and III Locomotives Michelle Bergin, GA Environmental Protection Division Matthew Harrell, IL Environmental Protection Agency Mark Janssen, Lake Michigan Air Directors Consortium Acknowledgments: Steve Sullivan, American Short Line and Regional Railroad Association David Powell, Genesee & Wyoming Inc. Dennis McGeen, Michigan Dept. of Environmental Quality Lisa Higgins, Maine Dept. of Environmental Protection Laurel Driver, US EPA, Office of Air Quality Planning and Support Byeong Kim, GA Environmental Protection Division Introduction Air protection agencies from twenty-seven states, coordinated through the Eastern Regional Technical Advisory Committee (ERTAC) and headed by the Lake Michigan Air Directors Consortium (LADCO), identified a need to better quantify and characterize rail-related emissions inventories. Traditional locomotives utilize large diesel engines, resulting in emissions of NO x, diesel PM, hydrocarbons, greenhouse gases, and other air pollutants. These emissions are sometimes concentrated in areas exceeding National Ambient Air Quality Standards. No cohesive nationwide railroad emission estimates based on local operations are known to have been made previously. Inventory development methods for locomotive emissions estimates vary from state to state and, in general, lack the spatial or temporal resolution needed to support air quality modeling and planning 1-5. The ERTAC Rail Subcommittee (ERTAC Rail) was established with active representatives from twelve member states, three regional planning offices, and the US EPA. The subcommittee’s goals are to (1) standardize agencies’ inventory development methods through a collaborative effort, (2) improve the quality of data received and the resulting emission inventories, and (3) reduce the administrative burden on railroad companies of providing data. -

CP's North American Rail

2020_CP_NetworkMap_Large_Front_1.6_Final_LowRes.pdf 1 6/5/2020 8:24:47 AM 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Lake CP Railway Mileage Between Cities Rail Industry Index Legend Athabasca AGR Alabama & Gulf Coast Railway ETR Essex Terminal Railway MNRR Minnesota Commercial Railway TCWR Twin Cities & Western Railroad CP Average scale y y y a AMTK Amtrak EXO EXO MRL Montana Rail Link Inc TPLC Toronto Port Lands Company t t y i i er e C on C r v APD Albany Port Railroad FEC Florida East Coast Railway NBR Northern & Bergen Railroad TPW Toledo, Peoria & Western Railway t oon y o ork éal t y t r 0 100 200 300 km r er Y a n t APM Montreal Port Authority FLR Fife Lake Railway NBSR New Brunswick Southern Railway TRR Torch River Rail CP trackage, haulage and commercial rights oit ago r k tland c ding on xico w r r r uébec innipeg Fort Nelson é APNC Appanoose County Community Railroad FMR Forty Mile Railroad NCR Nipissing Central Railway UP Union Pacic e ansas hi alga ancou egina as o dmon hunder B o o Q Det E F K M Minneapolis Mon Mont N Alba Buffalo C C P R Saint John S T T V W APR Alberta Prairie Railway Excursions GEXR Goderich-Exeter Railway NECR New England Central Railroad VAEX Vale Railway CP principal shortline connections Albany 689 2622 1092 792 2636 2702 1574 3518 1517 2965 234 147 3528 412 2150 691 2272 1373 552 3253 1792 BCR The British Columbia Railway Company GFR Grand Forks Railway NJT New Jersey Transit Rail Operations VIA Via Rail A BCRY Barrie-Collingwood Railway GJR Guelph Junction Railway NLR Northern Light Rail VTR -

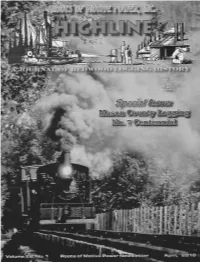

Mason County Logging No. 7 Centennial

lOOtS Of £1011¥[ trOWEl~ lMlC~ RooTs OF MoTIVE PoWER THE 2009-20 10 O FFICERS & DIRECTORS JERRY MOORE .............. ... PRESIDENT IGHLINE WES BRUBACHER . .... VICE PRESIDENT BOBBIE YOKUM .... SECRETARY JACK WADE . .. .. .•. ..... TREASURER CHRIS BALDO .. .. DIRECTOR WES BRUBACHER . ... .... DIRECTOR This newsletter is the official publication of Roots of Motive KIRK GRAUX . ..... ... ...•. DIRECTOR Power, Inc., an organization associated with the Mendocino MIKE MEYER . .. .. .. DIRECTOR JERRY MOORE . DIRECTOR County Museum, and dedicated to the preservation, restora KEITH RONGEY tion and operation of logging and railroad equipment rep DIRECTOR JACK WADE . .. DIRECTOR resentative of California's North Coast region, 18 50s to the present. Roots of Motive Power is a California Non-profit ~ 501 (c)(3) Public Benefit Corporation. Membership cost: $35 RooTs OF MoTIVE PoWER STAFF annually; Regular Members vote for Officers and Directors, JACK WADE ..... .. .... NEWSLETTER EDITOR who decide the general policy and direction for the Asso BRUCE EVANS .. ..•..... SPECIAL EDITION EDITOR ciation. Mailing address: Post Office Box 1540, Willits, CA WENDY WILMES .. .. .. NEWSLETTER PROOFREADER 95490. The Roots of Motive Power facilitiy and exhibit area (VACANT) ... ..... .. ... LIBRARIAN is located at 420 East Commercial Street, W illits, CA. Steam MARGERY HOPPNER .. .... ASSISTANT LIBRARIAN ups generally occur four times per year, plus educational and BRUCE EVANS . CURATOR special events. The Highline is published each April, August JIM BRUGGERE . ... .... ROADMASTER and December. CHRIS BALDO . TRAINMASTER Submission deadlines: June 20 for the August issue; Oct. 24 CHRIS BALDO . .. CHIEF ENGINEER , STEAM for the December issue. WES BRUBACHER .... ... CHIEF ENGINEER , STEAM Information: Phone Jerry Moore, President, 707-459-2055 TROY JAMES ... CHIEF MECHANICAL OFFICER , STEAM or Jack Wade, Treasurer, 707-459-9036. -

October 2017

May 2017 Error! No text of specified style in document. fff October 2017 September 2016 E r r o r ! No text of specified style in document. | i Indiana State Rail Plan Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................ S-1 S.1 PURPOSE OF THE INDIANA STATE RAIL PLAN .................................................................................................. S-1 S.2 VISION, GOALS AND OBJECTIVES ................................................................................................................. S-1 S.3 INDIANA RAIL NETWORK ............................................................................................................................ S-3 S.4 PASSENGER RAIL ISSUES, OPPORTUNITIES, PROPOSED INVESTMENTS AND IMPROVEMENTS ................................... S-7 S.5 SAFETY/CROSSING ISSUES, PROPOSED INVESTMENTS AND IMPROVEMENTS ....................................................... S-9 S.6 FREIGHT RAIL ISSUES, PROPOSED INVESTMENTS, AND IMPROVEMENTS .............................................................. S-9 S.7 RAIL SERVICE AND INVESTMENT PROGRAM ................................................................................................ S-12 1 THE ROLE OF RAIL IN STATEWIDE TRANSPORTATION (OVERVIEW) ................................................ 1 1.1 PURPOSE AND CONTENT .............................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 MULTIMODAL