Flying Denali Heavyweight P–51 Engine-Out LANDING UPHILL, on ICE P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

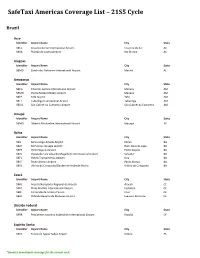

Safetaxi Americas Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle

SafeTaxi Americas Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle Brazil Acre Identifier Airport Name City State SBCZ Cruzeiro do Sul International Airport Cruzeiro do Sul AC SBRB Plácido de Castro Airport Rio Branco AC Alagoas Identifier Airport Name City State SBMO Zumbi dos Palmares International Airport Maceió AL Amazonas Identifier Airport Name City State SBEG Eduardo Gomes International Airport Manaus AM SBMN Ponta Pelada Military Airport Manaus AM SBTF Tefé Airport Tefé AM SBTT Tabatinga International Airport Tabatinga AM SBUA São Gabriel da Cachoeira Airport São Gabriel da Cachoeira AM Amapá Identifier Airport Name City State SBMQ Alberto Alcolumbre International Airport Macapá AP Bahia Identifier Airport Name City State SBIL Bahia-Jorge Amado Airport Ilhéus BA SBLP Bom Jesus da Lapa Airport Bom Jesus da Lapa BA SBPS Porto Seguro Airport Porto Seguro BA SBSV Deputado Luís Eduardo Magalhães International Airport Salvador BA SBTC Hotéis Transamérica Airport Una BA SBUF Paulo Afonso Airport Paulo Afonso BA SBVC Vitória da Conquista/Glauber de Andrade Rocha Vitória da Conquista BA Ceará Identifier Airport Name City State SBAC Aracati/Aeroporto Regional de Aracati Aracati CE SBFZ Pinto Martins International Airport Fortaleza CE SBJE Comandante Ariston Pessoa Cruz CE SBJU Orlando Bezerra de Menezes Airport Juazeiro do Norte CE Distrito Federal Identifier Airport Name City State SBBR Presidente Juscelino Kubitschek International Airport Brasília DF Espírito Santo Identifier Airport Name City State SBVT Eurico de Aguiar Salles Airport Vitória ES *Denotes -

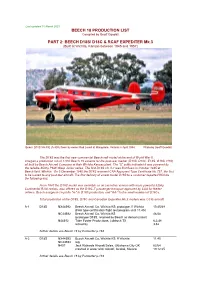

BEECH D18S/ D18C & RCAF EXPEDITER Mk.3 (Built at Wichita, Kansas Between 1945 and 1957)

Last updated 10 March 2021 BEECH 18 PRODUCTION LIST Compiled by Geoff Goodall PART 2: BEECH D18S/ D18C & RCAF EXPEDITER Mk.3 (Built at Wichita, Kansas between 1945 and 1957) Beech D18S VH-FIE (A-808) flown by owner Rod Lovell at Mangalore, Victoria in April 1984. Photo by Geoff Goodall The D18S was the first new commercial Beechcraft model at the end of World War II. It began a production run of 1,800 Beech 18 variants for the post-war market (D18S, D18C, E18S, G18S, H18), all built by Beech Aircraft Company at their Wichita Kansas plant. The “S” suffix indicated it was powered by the reliable 450hp P&W Wasp Junior series. The first D18S c/n A-1 was first flown in October 1945 at Beech field, Wichita. On 5 December 1945 the D18S received CAA Approved Type Certificate No.757, the first to be issued to any post-war aircraft. The first delivery of a new model D18S to a customer departed Wichita the following day. From 1947 the D18C model was available as an executive version with more powerful 525hp Continental R-9A radials, also offered as the D18C-T passenger transport approved by CAA for feeder airlines. Beech assigned c/n prefix "A-" to D18S production, and "AA-" to the small number of D18Cs. Total production of the D18S, D18C and Canadian Expediter Mk.3 models was 1,035 aircraft. A-1 D18S NX44592 Beech Aircraft Co, Wichita KS: prototype, ff Wichita 10.45/48 (FAA type certification flight test program until 11.45) NC44592 Beech Aircraft Co, Wichita KS 46/48 (prototype D18S, retained by Beech as demonstrator) N44592 Tobe Foster Productions, Lubbock TX 6.2.48 retired by 3.52 further details see Beech 18 by Parmerter p.184 A-2 D18S NX44593 Beech Aircraft Co, Wichita KS: ff Wichita 11.45 NC44593 reg. -

Va-Vol-44-No-6-Nov-Dec-2016

NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2016 Cruising the Vintage Line Vintage Airplane Straight & Level STAFF GEOFF ROBISON EAA Publisher/Chairman of the Board VAA PRESIDENT, EAA Lifetime 268346, VAA Lifetime 12606 . Jack J. Pelton Editor ............... Jim Busha . [email protected] VAA Executive Administrator . Hannah Hupfer 2016 — Certainly, a year to remember! 920-426-6110 .......... [email protected] Art Director ............ Olivia Phillip Trabbold Happy Thanksgiving and Merry Christmas to all of our members! Graphic Designer .......Amanda Million I believe 2016 was certainly an exceptional year for the membership of the VAA. But for me personally, I felt it was just a great year for some of the ADVERTISING: Vice President of Business Development best accomplishments we as an organization have executed on in recent Dave Chaimson ......... [email protected] times. I am always amazed every year to see how generous the VAA mem- Advertising Manager bership is to this organization. We actually received significant financial Sue Anderson .......... [email protected] support from a very broad base of our membership. Whether it’s you sup- porting the Friends of the Red Barn fund, or donating dollars designated VAA, PO Box 3086, Oshkosh, WI 54903 toward supporting the new construction at the Vintage Tall Pines Cafe, or Website: www.vintageaircraft.org Email: [email protected] incoming funds directed toward the funding of the numerous individual programs we offer each year during AirVenture, they all add up to being VISIT very significant in our endeavors to constantly improve the offerings we www.vintageaircraft.org provide the membership at Oshkosh each year. for the latest in information and news AirVenture Oshkosh 2016 was an absolute success story when you take and for the electronic newsletter: a true measurement of the number and quality of the features and attrac- Vintage AirMail tions on the field this year. -

Textron Inc. Annual Report 2018

Textron Inc. Annual Report 2018 Form 10-K (NYSE:TXT) Published: February 15th, 2018 PDF generated by stocklight.com UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form 10-K [ x ] ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 30, 2017 or [ ] TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to . Commission File Number 1-5480 Textron Inc. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 05-0315468 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) 40 Westminster Street, Providence, RI 02903 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip code) Registrants Telephone Number, Including Area Code: (401) 421-2800 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Name of Each Exchange on Which Title of Each Class Registered Common Stock par value $0.125 New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ü No___ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes No ü Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

•Flying a Helio Courier •Airventure Awards •Vin Fiz Straight & Level Vintage Airplane GEOFF ROBISON STAFF VAA PRESIDENT, EAA 268346, VAA 12606 EAA Publisher

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2013 Super CUB One •Flying a Helio Courier •AirVenture Awards •Vin Fiz Straight & Level Vintage Airplane GEOFF ROBISON STAFF VAA PRESIDENT, EAA 268346, VAA 12606 EAA Publisher . .Jack J . Pelton, . .Chairman of the Board Editor-in-Chief . J . Mac McClellan Editor . Jim Busha Oshkosh 2013 is now . [email protected] VAA Executive Administrator Max Platts in the history books 920-426-6110 . [email protected] Advertising Director . Katrina Bradshaw 202-577-9292 . [email protected] Uppermost in the minds of many of our members today is the Advertising Manager . Sue Anderson recent FAA action to assess operational fees for air traffic control ser- 920-426-6127 . [email protected] vices at AirVenture Oshkosh. To me, this is a particularly troublesome Art Director . Livy Trabbold development that arises out of the issues relevant to sequestration as VAA, PO Box 3086, Oshkosh, WI 54903 it was applied to the FAA. Early on in this debate Congress responded Website: www.VintageAircraft.org by exempting the FAA from the budget cuts that sequestration im- Email: [email protected] posed on them. Of course, we all wrongly assumed that this would eliminate the then “proposed” fees placed on AirVenture Oshkosh. This very burdensome level of fees is really an unfair tax on a signifi- cant aviation event that has been leveled by the FAA without any authority whatsoever to act in this manner. My real purpose here is to merely reach out to our membership and encourage you all to TM continue to communicate to your representatives in Washington our strong displeasure with this unauthorized attack on general aviation. -

PDF Version April May 2008

MIDWEST FLYER MAGAZINE APRIL/MAY 2008 Celebrating 30 Years Published For & By The Midwest Aviation Community Since 1978 midwestflyer.com Cessna Sales Team Authorized Representative for: J.A. Aero Aircraft Sales IL, WI & Upper MI Caravan Sales for: 630-584-3200 IL, WI & MO Largest Full-Service Cessna Dealer in Midwest See the Entire Cessna Propeller Line – From SkyCatcher Thru Caravan Delivery Positions on New Cessna 350 & 400! Scott Fank – Email: [email protected] Chicago’s DuPage Airport (DPA) Dave Kay – Email: [email protected] +2%.+ 6!./$%#+ Visit Us Online at (630) 584-3200 www.jaaero.com (630) 613-8408 Fax Upgrade or Replace? WWAASAAS isis Here!Here! The Choice is Yours Upgrade Your Unit OR Exchange for Brand New New Hardware / New Software / New 2 Year Warranty Call J.A. Air Center today to discuss which is the best option for you. Illinois 630-584-3200 + Toll Free 800-323-5966 Email [email protected] & [email protected] Web www.jaair.com * Certain Conditions= FBOand Services Restrictions Apply Avionics Sales and Service Instrument Sales and Service Piston and Turbine Maintenance Mail Order Sales Cessna Sales Team Authorized Representative for: J.A. Aero Aircraft Sales IL, WI & Upper MI VOL. 30, NO. 3 ISSN:0194-5068 Caravan Sales for: 630-584-3200 IL, WI & MO CONTENTS ON THE COVER: “Touch & Go At Sunset.” Photo taken at Middleton Municipal Airport – Morey Field (C29), Middleton, Wis. by Geoff Sobering MIDWEST FLYER MAGAZINE APRIL/MAY 2008 COLUMNS AOPA Great Lakes Regional Report - by Bill Blake ........................................................................ 24 Aviation Law - by Greg Reigel ......................................................................................................... 26 Largest Full-Service Cessna Dialogue - by Dave Weiman .......................................................................................................... -

Form 10-K Textron Inc

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form 10-K [ x ] ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 29, 2018 or [ ] TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to . Commission File Number 1-5480 Textron Inc. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 05-0315468 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) 40 Westminster Street, Providence, RI 02903 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip code) Registrant’s Telephone Number, Including Area Code: (401) 421-2800 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered Common Stock — par value $0.125 New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicat e by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ü No___ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes No ü Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Cessna Turbo Skyhawk Jet-A

n o i t a i v A n o r t x e T : o t o h P 8 MAGAZINE 1 0 2 Cessna Turbo Skyhawk Jet-A L’AVIATEUR R E I ou comment s'affranchir de l'Avgas R V É F G500 ET G600 NOUVELLE GÉNÉRATION / s R La solution «glass cockpit» lu E p I V N ENJEUX A LE MAGAZINE DE J Le legs du ministre Garneau? ESSAI EN VOL Cessna Turbo Skyhawk Jet-A ou comment s'affranchir de l'Avgas Texte : Richard Saint-George / Photos : Richard Saint-George et Textron Aviation Certifiée depuis juin 2017, cette version diesel permet d'ouvrir de nouveaux horizons au 172 sexagénaire. En effet, là où l'essence 100LL se fait rare et/ou dispen- dieuse, le ravitaillement en Jet-A – ou alternativement en diesel automobile – facilite les opérations autant privées que commerciales. Puissant, économique et silencieux, le Continental, couplé à une mt-Propeller de dernière génération, satisfera les pilotes les plus exigeants. La sphère aéronautique considère, à juste titre, le Cessna 172 essence (dévolu au trajet et à usages multiples), puis ren - comme le premier avion d'entraînement au monde. voient le stock comptabilisé, dans une caisse, chez Cessna. Construit à plus de 44 000 exemplaires – toutes séries Ils posent ensuite un nouveau bâti-moteur sur lequel est confondues – celui-ci vole sur tous les continents. greffé illico un CD-155 muni d'une tripale mt-Propeller. Aujourd'hui rebaptisé simplement Skyhawk S ou Turbo Même si l'avion est neuf, il s'agit bel et bien d'une modifica - Skyhawk Jet-A, le quadriplace emblématique se décline uni - tion accompagnée d'un STC ou Certificat de type supplémen - quement en deux variantes : essence et diesel. -

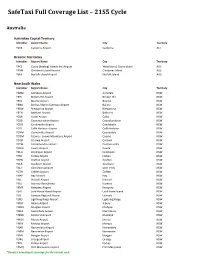

Safetaxi Full Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle

SafeTaxi Full Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle Australia Australian Capital Territory Identifier Airport Name City Territory YSCB Canberra Airport Canberra ACT Oceanic Territories Identifier Airport Name City Territory YPCC Cocos (Keeling) Islands Intl Airport West Island, Cocos Island AUS YPXM Christmas Island Airport Christmas Island AUS YSNF Norfolk Island Airport Norfolk Island AUS New South Wales Identifier Airport Name City Territory YARM Armidale Airport Armidale NSW YBHI Broken Hill Airport Broken Hill NSW YBKE Bourke Airport Bourke NSW YBNA Ballina / Byron Gateway Airport Ballina NSW YBRW Brewarrina Airport Brewarrina NSW YBTH Bathurst Airport Bathurst NSW YCBA Cobar Airport Cobar NSW YCBB Coonabarabran Airport Coonabarabran NSW YCDO Condobolin Airport Condobolin NSW YCFS Coffs Harbour Airport Coffs Harbour NSW YCNM Coonamble Airport Coonamble NSW YCOM Cooma - Snowy Mountains Airport Cooma NSW YCOR Corowa Airport Corowa NSW YCTM Cootamundra Airport Cootamundra NSW YCWR Cowra Airport Cowra NSW YDLQ Deniliquin Airport Deniliquin NSW YFBS Forbes Airport Forbes NSW YGFN Grafton Airport Grafton NSW YGLB Goulburn Airport Goulburn NSW YGLI Glen Innes Airport Glen Innes NSW YGTH Griffith Airport Griffith NSW YHAY Hay Airport Hay NSW YIVL Inverell Airport Inverell NSW YIVO Ivanhoe Aerodrome Ivanhoe NSW YKMP Kempsey Airport Kempsey NSW YLHI Lord Howe Island Airport Lord Howe Island NSW YLIS Lismore Regional Airport Lismore NSW YLRD Lightning Ridge Airport Lightning Ridge NSW YMAY Albury Airport Albury NSW YMDG Mudgee Airport Mudgee NSW YMER -

99 News Letters; the Struction Offers Tremendous Promise for Batavia, Ohio 45103 American Weekly, July 19, 1953; Jean Achieving That Goal

OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION OF WOMEN PILOTS SSmus In This Issue: 99s — What It Means ty - heme of WACOA Fall Meeting d News From Beech re To Fly ff it w S S n E iu s Spotlighting JANUARY 1973 VOLUME 15 NUMBER 1 THE NINETY-NINES, INC. Will Rogers World Airport The International Headquarters Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73159 International President Return Form 3579 to above address 2nd Class Postage pd. at North Little Rock. Ark. It is November 17th and the fog is thick this morning as P u b lis h e r......................................... Lee Keenihan I look out the window here in Sacramento, California. Managing Editor ...........................Mardo Crane The gray skies are predicted to clear soon for the mem Assistant Editor ...............................Betty Hicks bers flying in for the 25th Anniversary Celebration of the Art Director.................................... Lucille Nance Sacramento Valley Chapter. Several happy faces greeted Production Manager Ron Oberlag us at the airport on our arrival in the rain last night and we Circulation Manager................... Loretta Gragg chatted while we waited for the luggage to come off the big DC-8. Broneta Davis Evans (past president) had flown Contributing Editors Gene FitzPatrick out with me and we were enjoying ourselves visiting with •'Wally" Funk Darlene Gilmore, Gerry Mickelson (also a past president), Virginia Thompson Barbara Goetz, Barbara Foster, Shirley and Ernie Lehr. Director of Advertising ...................Paula Reed Then the moment of realization finally arrived — like the Susie Sewell head-on collision which only happens to other people — our luggage didn’t show up, so obviously it didn't get on the plane at Los Angeles. -

Striking Gold Australian Charter Firm Serves Mining Companies

A MAGAZINE FOR THE OWNER/PILOT OF KING AIR AIRCRAFT MAY 2017 • VOLUME 11, NUMBER 5 • $6.50 Striking Gold Australian Charter Firm Serves Mining Companies A MAGAZINE FOR THE OWNER/PILOT OF KING AIR AIRCRAFT King MAY 2017 VolumeAir 11 / Number 5 2 10 12 20 EDITOR Kim Blonigen EDITORIAL OFFICE 2779 Aero Park Dr., Traverse City MI 49686 Contents Phone: (316) 652-9495 E-mail: [email protected] PUBLISHERS J. Scott Lizenby 2 27 Dave Moore Village Publications Mining the King Air Value Added by MeLinda Schnyder GRAPHIC DESIGN Luana Dueweke PRODUCTION MANAGER Mike Revard 29 PUBLICATIONS DIRECTOR 10 Technically... Jason Smith Dealing with ADVERTISING DIRECTOR Annoying Allergies John Shoemaker King Air Magazine by Dr. Jerrold Seckler 2779 Aero Park Drive Traverse City, MI 49686 32 Phone: 1-800-773-7798 Fax: (231) 946-9588 Advertiser Index E-mail: [email protected] 12 ADVERTISING EXECUTIVE ASSISTANT Betsy Beaudoin Ask the Expert: Phone: 1-800-773-7798 E-mail: [email protected] Abort! Abort! by Tom Clements SUBSCRIBER SERVICES Rhonda Kelly, Mgr. Diane Chauvin Molly Costilow Jamie Wilson P.O. Box 1810 Traverse City, MI 49685 20 1-800-447-7367 The “Baby Beechcraft” ONLINE ADDRESS – Part One www.kingairmagazine.com by Edward H. Phillips SUBSCRIPTIONS King Air is distributed at no charge to all registered owners of King Air aircraft. The mailing list is updated bi-monthly. All others may sub scribe by writing to: King Air, P.O. Box 1810, Traverse City, King Air is wholly owned by Village Press, Inc. and is in no way associated with or a product of Textron Aviation. -

Form 10-K Textron Inc

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form 10-K [ x ] ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended January 2, 2016 or [ ] TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to . Commission File Number 1-5480 Textron Inc. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 05-0315468 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) 40 Westminster Street, Providence, RI 02903 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip code) Registrant’s Telephone Number, Including Area Code: (401) 421-2800 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered Common Stock — par value $0.125 New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ü No___ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes No ü Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days.