Aiza Khan Professor Reza Pirbhai ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By Beheshta Jaehori B.Sc. (Hon.), University of Toronto, 2001 A

AFGHAN WOME,N'S EXPERIENCESDURNG THE TALIBAN REGIME by BeheshtaJaehori B.Sc.(Hon.), University of Toronto,2001 A THESISSUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FORTHE DEGREEOF MASTEROF ARTS in The Facultyof GraduateStudies (CounsellingPsychology) THE LINIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLLMBIA (Vancouver) August,2009 @ BeheshtaJaghori, 2009 Abstract A plethoraof researchhas depictedAfghan women during the Talibanreign in a varietyof ways,ranging from oppressed"victims of the burqa" to heroic "social actors." In this study, I examinedthe lived experiencesof women in Afghanistanunder the Talibanregime, as articulatedby ordinarywomen themselves.Data from 11 women were gatheredthrough the use of individual interviews,and analyzedusing Miles and Hubermans'(1994) analytic framework. Themes emerged that describedthe Taliban regime'spolicies regarding Afghan women,the overallresponses of women to the policies,including the impactof thosepolicies at the time (1996-2001),the ongoing impact,and the situationof women in the post-Talibanera. The Talibanregime's anti-women policies denied women education,employment, and freedomof movement.Those who committedany infractionswere met with severe punishment.The impact of thesepolicies led to variouspsychological effects, including: anxiety,fear, and synptoms of depressionand posttraumatic stress. Despite the condemnablerestrictions, Afghan women's agency,no matterhow limited, was present andcontinuously exercised on differentoccasions. Despite the gainsfor somewomen, eightyears after the removalof the Talibanregime, Afghan women still do not appearto havemade substantive progress with regardto oppressivecustoms, violence, and their positionin Afghan society.The studyresults and their analysisis especiallytimely, given the increasingTaliban insurgencyin Afghanistan,and the looming possibility of a resurrectedTaliban rule in the countrv. 111 Table of Contents Abstract .........ii Tableof Contents.. ....iii Acknowledgments.... ......viii ChapterOne: Introduction. .........1 Situatingthe Researcher .....2 Summary.... -

CAPSTONE 20-1 SWA Field Study Trip Book Part II

CAPSTONE 20-1 SWA Field Study Trip Book Part II Subject Page Afghanistan ................................................................ CIA Summary ......................................................... 2 CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 3 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 24 Culture Gram .......................................................... 30 Kazakhstan ................................................................ CIA Summary ......................................................... 39 CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 40 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 58 Culture Gram .......................................................... 62 Uzbekistan ................................................................. CIA Summary ......................................................... 67 CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 68 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 86 Culture Gram .......................................................... 89 Tajikistan .................................................................... CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 99 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 117 Culture Gram .......................................................... 121 AFGHANISTAN GOVERNMENT ECONOMY Chief of State Economic Overview President of the Islamic Republic of recovering -

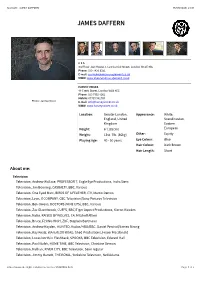

James Daffern 15/09/2020, 21�09

Spotlight: JAMES DAFFERN 15/09/2020, 2109 JAMES DAFFERN C S A 3rd Floor Joel House, 17-21 Garrick Street, London WC2E 9BL Phone: 020-7420 9351 E-mail: [email protected] WWW: www.shepherdmanagement.co.uk HARVEY VOICES 49 Greek Street, London W1D 4EG Phone: 020 7952 4361 Mobile: 07739 902784 Photo: Jennie Scott E-mail: [email protected] WWW: www.harveyvoices.co.uk Location: Greater London, Appearance: White, England, United Scandinavian, Kingdom Eastern Height: 6' (182cm) European Weight: 13st. 7lb. (86kg) Other: Equity Playing Age: 40 - 50 years Eye Colour: Blue Hair Colour: Dark Brown Hair Length: Short About me: Television Television, Andrew Wallace, PROFESSOR T, Eagle Eye Productions, Indra Siera Television, Jim Bonning, CASUALTY, BBC, Various Television, One Eyed Marc, BIRDS OF A FEATHER, ITV, Martin Dennis Television, Leon, X COMPANY, CBC Television/Sony Pictures Television Television, Ben Owens, DOCTORS (NINE EPS), BBC, Various Television, Zac Glazerbrook, CUFFS, BBC/Tiger Aspect Productions, Kieron Hawkes Television, Natie, RAISED BY WOLVES, C4, Mitchell Altieri Television, Bruce, FLYING HIGH, ZDF, Stephen Bartmann Television, Andrew Hayden, HUNTED, Kudos/HBO/BBC, Daniel Percival/James Strong Television, Ray Keats, WATERLOO ROAD, Shed Productions, Fraser Macdonald Television, Lucas North in Flashback, SPOOKS, BBC Television, Edward Hall Television, Paul Walsh, HOME TIME, BBC Television, Christine Gernon Television, Nathan, RIVER CITY, BBC Television, Semi regular Television, Jimmy Barrett, THE ROYAL, Yorkshire Television, -

Spooks Returns to Dvd

A BAPTISM OF FIRE FOR THE NEW TEAM AS SPOOKS RETURNS TO DVD SPOOKS: SERIES NINE AVALIABLE ON DVD FROM 28TH FEBRUARY 2011 “Who doesn’t feel a thrill of excitement when a new series of Spooks hits our screens?” Daily Mail “It’s a tribute to Spooks’ staying power that after eight years we still care so much” The Telegraph BAFTA Award‐winning British television spy drama Spooks is back for its ninth knuckle‐clenching series and is available on DVD from 28th February 2011 courtesy of Universal Playback. Filled with spy‐tastic extra features, the DVD is a must for any die‐hard Spooks fan. The ninth series of the critically acclaimed Spooks, is filled with dramatic revelations and a host of new characters ‐ Sophia Myles (Underworld, Doctor Who), Max Brown (Mistresses, The Tudors), Iain Glen (The Blue Room, Lara Croft: Tomb Raider), Simon Russell Beale (Much Ado About Nothing, Uncle Vanya) and Laila Rouass (Primeval, Footballers’ Wives). Friendships will be tested and the depth of deceit will lead to an unprecedented game of cat and mouse and the impact this has on the team dynamic will have viewers enthralled. Follow the team on a whirlwind adventure tracking Somalian terrorists, preventing assassination attempts, avoiding bomb efforts and vicious snipers, and through it all face the personal consequences of working for the MI5. The complete Spooks: Series 9 DVD boxset contains never before seen extras such as a feature on The Cost of Being a Spy and a look at The Downfall of Lucas North. Episode commentaries with the cast and crew will also reveal secrets that have so far remained strictly confidential. -

A Case Study of Mahsud Tribe in South Waziristan Agency

RELIGIOUS MILITANCY AND TRIBAL TRANSFORMATION IN PAKISTAN: A CASE STUDY OF MAHSUD TRIBE IN SOUTH WAZIRISTAN AGENCY By MUHAMMAD IRFAN MAHSUD Ph.D. Scholar DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF PESHAWAR (SESSION 2011 – 2012) RELIGIOUS MILITANCY AND TRIBAL TRANSFORMATION IN PAKISTAN: A CASE STUDY OF MAHSUD TRIBE IN SOUTH WAZIRISTAN AGENCY Thesis submitted to the Department of Political Science, University of Peshawar, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Award of the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE (December, 2018) DDeeddiiccaattiioonn I Dedicated this humble effort to my loving and the most caring Mother ABSTRACT The beginning of the 21st Century witnessed the rise of religious militancy in a more severe form exemplified by the traumatic incident of 9/11. While the phenomenon has troubled a significant part of the world, Pakistan is no exception in this regard. This research explores the role of the Mahsud tribe in the rise of the religious militancy in South Waziristan Agency (SWA). It further investigates the impact of militancy on the socio-cultural and political transformation of the Mahsuds. The study undertakes this research based on theories of religious militancy, borderland dynamics, ungoverned spaces and transformation. The findings suggest that the rise of religious militancy in SWA among the Mahsud tribes can be viewed as transformation of tribal revenge into an ideological conflict, triggered by flawed state policies. These policies included, disregard of local culture and traditions in perpetrating military intervention, banning of different militant groups from SWA and FATA simultaneously, which gave them the raison d‘etre to unite against the state and intensify violence and the issues resulting from poor state governance and control. -

Warsi 4171.Pdf

Warsi, Sahil K. (2015) Being and belonging in Delhi: Afghan individuals and communities in a global city. PhD thesis. SOAS University of London. http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/22782/ Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Being and Belonging in Delhi: Afghan Individuals and Communities in a Global City Sahil K. Warsi Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD 2015 Department of Anthropology and Sociology SOAS, University of London 1 Declaration for SOAS PhD thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the SOAS, University of London concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination. -

Cultural Simulation and the Applications of Culturally Enabled

CULTURAL SIMULATION AND THE APPLICATIONS OF CULTURALLY ENABLED GAMES AND TECHNOLOGY by Jumanne K. Donahue APPROVED BY SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: ___________________________________________ Marjorie Zielke, Chair ___________________________________________ Dean Terry ___________________________________________ Frederick Turner ___________________________________________ Habte Woldu Copyright 2017 Jumanne K. Donahue All Rights Reserved This dissertation is dedicated to the civilized, humane, rational, and creative people of the world. May you increase in number. Your wise actions are sorely needed. CULTURAL SIMULATION AND THE APPLICATIONS OF CULTURALLY ENABLED GAMES AND TECHNOLOGY by JUMANNE K. DONAHUE, BS, MFA DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The University of Texas at Dallas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ARTS, TECHNOLOGY, AND EMERGING COMMUNICATION THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT DALLAS December 2017 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To begin, I would like to like to thank my supervisor, Dr. Marjorie Zielke. I appreciate your support and guidance given the unorthodox confluence of ideas in my dissertation as well as your confidence in me and your leadership of The First Person Cultural Trainer project. I would also like to think the members of my committee: Dr. Frederick Turner, Dean Terry, and Dr. Habte Woldu. Dr. Turner, you are a gentleman, scholar, and writer of the first order and your work on epic narrative has been enlightening. Dean Terry, your knowledge of avant-garde cinema and role as an innovator in social technology has always made our conversations stimulating. Your example encourages me to take risks with my own endeavors and to strive for the vanguard. Dr. Woldu, you introduced me to the concept of quantifying cultural values. -

Representation of Pashtun Culture in Pashto Films Posters: a Semiotic Analysis

DOI: 10.31703/glr.2020(V-I).29 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.31703/glr.2020(V-I).29 Citation: Mukhtar, Y., Iqbal, L., & Rehman, F. (2020). Representation of Pashtun Culture in Pashto Films Posters: A Semiotic Analysis. Global Language Review, V(I), 281-292. doi:10.31703/glr.2020(V-I).29 Yusra Mukhtar* Liaqat Iqbal† Faiza Rehman‡ p-ISSN: 2663-3299 e-ISSN: 2663-3841 L-ISSN: 2663-3299 Vol. V, No. I (Winter 2020) Pages: 281- 292 Representation of Pashtun Culture in Pashto Films Posters: A Semiotic Analysis Abstract: Introduction The purpose of the research is to investigate It is in the nature of human beings to infer meaning out of every the representation or misrepresentation of word they hear, every object they see and every act they observe. Pashtun culture through the study of It is because whatever we hear, see or observe may suggest different signs and to inspect that how these deeper and broader interpretation than its explicit signs relate to Pashtun culture by employing representation. All of these can be taken as distinct signs, semiotics as a tool. To achieve the goal, which is anything that indicates or is referred to as something twelve distinct Pashto film posters that were other than itself. Signs hold the meaning and convey it to the published during 2011-2017 were selected and categorized under poster design, interpreter for inferring meaning out of it; for example, the dressing, props and titles, as these aspects traffic lights direct the traffic without using verbal means of act as signs for depicting cultural insights. -

SECOND-GENERATION AFGHANS in NEIGHBOURING COUNTRIES from Mohajer to Hamwatan: Afghans Return Home

From mohajer to hamwatan: Afghans return home Case Study Series SECOND-GENERATION AFGHANS IN NEIGHBOURING COUNTRIES From mohajer to hamwatan: Afghans return home Mamiko Saito Funding for this research was December 2007 provided by the European Commission (EC) and United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit i Second-Generation Afghans in Neighbouring Countries © 2007 Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, recording or otherwise without prior written permission of the publisher, the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit. Permission can be obtained by emailing [email protected] or calling +93 799 608 548. ii Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit From mohajer to hamwatan: Afghans return home About the Author Mamiko Saito is the senior research officer on migration at AREU. She has been work- ing in Afghanistan and Pakistan since 2003, and has worked with Afghan refugees in Quetta and Peshawar. She holds a master’s degree in education and development studies from the University of East Anglia, United Kingdom. About the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit The Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU) is an independent research organisation headquartered in Kabul. AREU’s mission is to conduct high-quality research that informs and influences policy and practice. AREU also actively pro- motes a culture of research and learning by strengthening analytical capacity in Afghanistan and facilitating reflection and debate. Fundamental to AREU’s vision is that its work should improve Afghan lives. -

Forbidden Faces: Effects of Taliban Rule

Forbidden Faces: Effects of Taliban Rule on Women in Afghanistan Overview In this lesson, students will explore the rise of Taliban power in Afghanistan and the impacts of Taliban rule upon Afghan women. Grade 9 North Carolina Essential Standards for World History • WH.8.3 ‐ Explain how liberal democracy, private enterprise and human rights movements have reshaped political, economic and social life in Africa, Asia, Latin America, Europe, the Soviet Union and the United States (e.g., U.N. Declaration of Human Rights, end of Cold War, apartheid, perestroika, glasnost, etc.). • WH.8.4‐ Explain why terrorist groups and movements have proliferated and the extent of their impact on politics and society in various countries (e.g., Basque, PLO, IRA, Tamil Tigers, Al Qaeda, Hamas, Hezbollah, Palestinian Islamic Jihad, etc.). Essential Questions • What is the relationship between Islam and the Taliban? • How does the Taliban try to control Afghan women? • How has the experience of Afghan women changed with the Taliban’s emergence? • What was the United States’ role in the Taliban coming to power? • How is clothing used as a means of oppression in Afghanistan? Materials • Overhead or digital projector • Post Its (four per student) • Value statements written on poster or chart paper: 1. I am concerned about being attacked by terrorists. 2. America has supported the Taliban coming into power. 3. All Muslims (people practicing Islam) support the Taliban. 4. I know someone currently deployed in Iraq or Afghanistan. • Opinion scale for each value statement -

ANCIENT SPOOKS Part III: Link to a Spooky Past

ANCIENT SPOOKS Part III: Link to a spooky past By Gerry, July 2018 Click here to read Eustace Mullins - The Curse Of Satanic Canaan; A Satanic Demonology Of History (1987) http://www.energyenhancement.org/ANCIENT-SPOOKS-I-Pun-Factor-Spookery- Curse-Of-Canaan-A-Satanic-Demonology-Of-History-The-War-Against-Shem- Transgression-of-Cain-Secular-Humanism.pdf http://www.energyenhancement.org/ANCIENT-SPOOKS-II-Spookish-relations- Curse-Of-Canaan-A-Satanic-Demonology-Of-History-England-French-Revolution- American-Revolution.pdf http://www.energyenhancement.org/ANCIENT-SPOOKS-III-Miles-Mathis-Link-to-a- spooky-past-Curse-Of-Canaan-A-Satanic-Demonology-Of-History-The-American- Civil-War-State-of-Virginia-World-Wars.pdf http://www.energyenhancement.org/ANCIENT-SPOOKS-IV-Miles-Mathis- Spookdom-history-Curse-Of-Canaan-A-Satanic-Demonology-Of-History-The- Menace-of-Communism-The-Promise.pdf Hello again, dear readers. I welcome you all to our central piece, where I am going to share my link to the Ancient Spookians, the progenitors of today’s hidden aristocracy. If you came here by coincidence and don’t know what I’m talking about, I’d suggest you read the other papers first. This one will be very uncomfortable since it concerns the Names of God. Yes, that God. I think some of God’s names were edited away, because either someone played around with those names, or the Biblical editors thought someone did, or the Biblical editors thought that some Biblical readers would think someone did. I am one of those readers. We’ll also see that the editors weren’t paranoid: A lot of Biblical material refers to Ancient Spookia, and a lot of puns as well. -

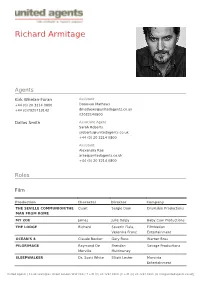

Richard Armitage

Richard Armitage Agents Kirk Whelan-Foran Assistant +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 Donovan Mathews +44 (0)7920713142 [email protected] 02032140800 Dallas Smith Associate Agent Sarah Roberts [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 Assistant Alexandra Rae [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 Roles Film Production Character Director Company THE SEVILLE COMMUNION/THE Quart Sergio Dow Drumskin Productions MAN FROM ROME MY ZOE James Julie Delpy Baby Cow Productions THE LODGE Richard Severin Fiala, FilmNation Veronika Franz Entertainment OCEAN'S 8 Claude Becker Gary Ross Warner Bros PILGRIMAGE Raymond De Brendan Savage Productions Merville Muldowney SLEEPWALKER Dr. Scott White Elliott Lester Marvista Entertainment United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Character Director Company BRAIN ON FIRE Tom Cahalan Gerard Barrett Broad Green Pictures ALICE THROUGH THE LOOKING King Oleron James Bobin Walt Disney Pictures GLASS URBAN AND THE SHED CREW Chop Candida Brady Blenheim Films THE HOBBIT: THE BATTLE OF Thorin Peter Jackson MGM THE FIVE ARMIES Oakenshield INTO THE STORM Gary Morris Steven Quale Broken Road/New Line THE HOBBIT - THE DESOLATION Thorin Peter Jackson MGM OF SMAUG Oakenshield THE HOBBIT - AN UNEXPECTED Thorin Peter Jackson MGM JOURNEY Oakenshield CAPTAIN AMERICA: THE FIRST Heinz Kruger Joe Johnston Marvel AVENGER CLEOPATRA Epiphanes Frank Roddan Alexandria Films FROZEN Steven Juliet McKoen Liminal Films MACBETH Angus