Love Tokens in the Lai De L'ombre Barry O'neill Center For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INTERPRETING POETRY: English and Scottish Folk Ballads (Year 5, Day Department, 2016) Assignments for Self-Study (25 Points)

The elective discipline «INTERPRETING POETRY: English and Scottish Folk Ballads (Year 5, day department, 2016) Assignments for Self-Study (25 points) Task: Select one British folk ballad from the list below, write your name, perform your individual scientific research paper in writing according to the given scheme and hand your work in to the teacher: Titles of British Folk Ballads Students’ Surnames 1. № 58: “Sir Patrick Spens” 2. № 13: “Edward” 3. № 84: “Bonny Barbara Allen” 4. № 12: “Lord Randal” 5. № 169:“Johnie Armstrong” 6. № 243: “James Harris” / “The Daemon Lover” 7. № 173: “Mary Hamilton” 8. № 94: “Young Waters” 9. № 73:“Lord Thomas and Annet” 10. № 95:“The Maid Freed from Gallows” 11. № 162: “The Hunting of the Cheviot” 12. № 157 “Gude Wallace” 13. № 161: “The Battle of Otterburn” 14. № 54: “The Cherry-Tree Carol” 15. № 55: “The Carnal and the Crane” 16. № 65: “Lady Maisry” 17. № 77: “Sweet William's Ghost” 18. № 185: “Dick o the Cow” 19. № 186: “Kinmont Willie” 20. № 187: “Jock o the Side” 21. №192: “The Lochmaben Harper” 22. № 210: “Bonnie James Campbell” 23. № 37 “Thomas The Rhymer” 24. № 178: “Captain Car, or, Edom o Gordon” 25. № 275: “Get Up and Bar the Door” 26. № 278: “The Farmer's Curst Wife” 27. № 279: “The Jolly Beggar” 28. № 167: “Sir Andrew Barton” 29. № 286: “The Sweet Trinity” / “The Golden Vanity” 30. № 1: “Riddles Wisely Expounded” 31. № 31: “The Marriage of Sir Gawain” 32. № 154: “A True Tale of Robin Hood” N.B. You can find the text of the selected British folk ballad in the five-volume edition “The English and Scottish Popular Ballads: five volumes / [edited by Francis James Child]. -

A Collection of Ballads

A COLLECTION OF BALLADS INTRODUCTION When the learned first gave serious attention to popular ballads, from the time of Percy to that of Scott, they laboured under certain disabilities. The Comparative Method was scarcely understood, and was little practised. Editors were content to study the ballads of their own countryside, or, at most, of Great Britain. Teutonic and Northern parallels to our ballads were then adduced, as by Scott and Jamieson. It was later that the ballads of Europe, from the Faroes to Modern Greece, were compared with our own, with European Märchen, or children’s tales, and with the popular songs, dances, and traditions of classical and savage peoples. The results of this more recent comparison may be briefly stated. Poetry begins, as Aristotle says, in improvisation. Every man is his own poet, and, in moments of stronge motion, expresses himself in song. A typical example is the Song of Lamech in Genesis— “I have slain a man to my wounding, And a young man to my hurt.” Instances perpetually occur in the Sagas: Grettir, Egil, Skarphedin, are always singing. In Kidnapped, Mr. Stevenson introduces “The Song of the Sword of Alan,” a fine example of Celtic practice: words and air are beaten out together, in the heat of victory. In the same way, the women sang improvised dirges, like Helen; lullabies, like the lullaby of Danae in Simonides, and flower songs, as in modern Italy. Every function of life, war, agriculture, the chase, had its appropriate magical and mimetic dance and song, as in Finland, among Red Indians, and among Australian blacks. -

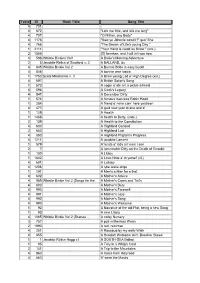

Table ID Book Titile Song Title 4

Table ID Book Titile Song Title 4 701 - 4 672 "Lo'e me little, and lo'e me lang" 4 707 "O Mither, ony Body" 4 1176 "Saw ye Johnnie comin'?" quo' She 4 766 "The Dream of Life's young Day " 1 2111 "Your Hand is cauld as Snaw " (xxx.) 2 1555 [O] hearken, and I will tell you how 4 596 Whistle Binkies Vol1 A Bailie's Morning Adventure 2 5 Jacobite Relics of Scotland v. 2 A BALLAND, &c 4 845 Whistle Binkie Vol 2 A Bonnie Bride is easy buskit 4 846 A bonnie wee lassie 1 1753 Scots Minstrelsie v. 3 A Braw young Lad o' High Degree (xxi.) 4 597 A British Sailor's Song 1 573 A cogie o' ale an' a pickle aitmeal 4 598 A Cook's Legacy 4 847 A December Dirty 1 574 A famous man was Robin Hood 1 284 A friend o' mine cam' here yestreen 4 477 A guid new year to ane and a' 1 129 A Health 1 1468 A health to Betty, (note,) 2 139 A Health to the Constitution 4 600 A Highland Garland 2 653 A Highland Lad 4 850 A Highland Pilgram's Progress 4 1211 A jacobite Lament 1 579 A' kinds o' lads an' men I see 2 7 A lamentable Ditty on the Death of Geordie 1 130 A Litany 1 1842 A Love-Note a' to yersel' (xi.) 4 601 A Lullaby 4 1206 A lyke wake dirge 1 291 A Man's a Man for a that 4 602 A Mother's Advice 4 989 Whistle Binkie Vol 2 (Songs for the A Mother's Cares and Toil's 4 603 Nursery) A Mother's Duty 4 990 A Mother's Farewell 4 991 A Mother's Joys 4 992 A Mother's Song 4 993 A Mother's Welcome 1 92 A Narrative of the old Plot; being a new Song 1 93 A new Litany 4 1065 Whistle Binkie Vol 2 (Scenes … A noisy Nursery 3 757 Nursery) A puir mitherless Wean 2 1990 A red, red rose 4 251 A Rosebud by my early Walk 4 855 A Scottish Welcome to H. -

Mcalpine (1995)

ýýesi. s ayoS THE GALLOWS AND THE STAKE: A CONSIDERATION OF FACT AND FICTION IN THE SCOTTISH BALLADS FOR MY PARENTS AND IN MEMORY OF NAN ANDERSON, WHO ALMOST SAW THIS COMPLETED iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Before embarking on the subject of hanging and burning, I would like to linger for a moment on a much more pleasant topic and to take this opportunity to thank everyone who has helped me in the course of my research. Primarily, thanks goes to all my supervisors, most especially to Emily Lyle of the School of Scottish Studies and to Douglas Mack of Stirling, for their support, their willingness to read through what must have seemed like an interminable catalogue of death and destruction, and most of all for their patience. I also extend thanks to Donald Low and Valerie Allen, who supervised the early stages of this study. Three other people whom I would like to take this opportunity to thank are John Morris, Brian Moffat and Stuart Allan. John Morris provided invaluable insight into Scottish printed balladry and I thank him for showing the Roseberry Collection to me, especially'The Last Words of James Mackpherson Murderer'. Brian Moffat, armourer and ordnancer, was a fount of knowledge on Border raiding tactics and historical matters of the Scottish Middle and West Marches and was happy to explain the smallest points of geographic location - for which I am grateful: anyone who has been on the Border moors in less than clement weather will understand. Stuart Allan of the Historic Search Room, General Register House, also deserves thanks for locating various documents and papers for me and for bringing others to my attention: in being 'one step ahead', he reduced my workload as well as his own. -

Poetic Origins and the Ballad

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications -- Department of English English, Department of January 1921 Poetic Origins and the Ballad Louise Pound University of Nebraska Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishfacpubs Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Pound, Louise, "Poetic Origins and the Ballad" (1921). Faculty Publications -- Department of English. 43. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishfacpubs/43 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications -- Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. POETIC ORIGINS AND THE BALLAD BY LOUISE POUND, Ph.D. Professor of English in the University of Nebraska )Sew ~Otft THE MACMILLAN COMPANY 1921 aU riuhta reserved COPYRIGHT, 1921, By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY. Set up and electrotyped. Published, January, 1921. TO HARTLEY AND NELLIE ALEXANDER PREFACE The leading theses of the present volume are that the following assumptions which have long dominated our thought upon the subject of poetic origins and the ballads should be given up, or at least should be seriously quali fied; namely, belief in the "communal" authorship and ownership of primitive poetry; disbelief in the primitive artist; reference to the ballad as the earliest and most universal poetic form; belief in the origin of narrative -

Nicol, Scott, and the Ballad Collectors DAVID D

Nicol, Scott, and the Ballad Collectors DAVID D. BUCHAN HE FIRST third of the nineteenth century saw a remarkable outpouring of Scottish ballad books. David Herd's Ancient T and Modern Scottish Songs had earlier led the way but it was undoubtedly Scott's Minstrelsy that stimulated the extraordinary run which included, amongst others, Charles Kirkpatrick Sharpe's A Ballad Boole (1823), James Maidment's A North C01l1ltrie Garland (182.4), Peter Buchan's Gleanings of Scotch, English, and Irish Scarce Old Ballads (182.5) and Ancient Ballads and Songs of the North of Scotland (1828), and William Motherwell's Minstrelsy, Ancient and Modern (182.7)' Scott's ballad collecting, ofcourse, has claimed due notice but the sources, methods, and relations of Scott's con temporaries have received comparatively scant attention.l One source of ballad texts was James Nicol of Strichen in Aberdeen shire; hitherto associated mainly with Buchan, he actually served Scott and a number ofcontemporary editors as well. An examina tion of his balladry and its editorial fortunes both reveals the extent and importance of Nicol's repertoire and provides an insight into the methods and interrelations ofthe early nineteenth century Scottish ballad collectors. It also answers a longstanding query about the Abbotsford Ballad MSS. James Nicol was no uneducated farm labourer. Though he received only a basic schooling he was, besides being something ofa character, a well-read and intelligent man, a disciple of Tom Paine, and the author of some pamphlets which set forth views quite advanced for his time: Letters written in zSz6, on infant education, etc. -

Francis James Child and William Macmath Working Together for Ballads

THE CAUSE Francis James Child and William Macmath Working Together for Ballads Mary Ellen Brown• • , Editor Contents Acknowledgements The Cause The Letters Index Acknowledgments The letters between Francis James Child and William Macmath reproduced here belong to the permanent collections of the Houghton Library, Harvard University and the Hornel Library, Broughton House, Kirkcudbright, a National Trust for Scotland property. I gratefully acknowledge the help and hospitality given me by the staffs of both institutions and their willingness to allow me to make these materials more widely available. My visits to both facilities in search of data, transcribing hundreds of letters to bring home and analyze, was initially provided by the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial and Andrew W. Mellon foundations and subsequently—for checking my transcriptions and gathering additional material--by the Office of the Provost for Research at Indiana University Bloomington. This serial support has made my work possible. Quite unexpectedly, two colleagues/friends met me the last time I was in Kirkcudbright (2014) and spent time helping me correct several difficult letters and sharing their own perspectives on these and other materials—John MacQueen and the late Ronnie Clark. Robert E. Lewis helped me transcribe more accurately Child’s reference and quotation from Chaucer; that help reminded me that many of the letters would benefit from copious explanatory notes in the future. Much earlier I benefitted from conversations with Sigrid Rieuwerts and throughout the research process with Emily Lyle. Both of their published and anticipated research touches on related publications as they have sought to explore and make known the rich past of Scots and the study of ballads. -

Xerox Univarsity Microfiims 300 North Zseb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatwt value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Mad Women, Mad World : the Depiction of Madness in Renaissance Drama

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Lehigh University: Lehigh Preserve Lehigh University Lehigh Preserve Theses and Dissertations 1994 Mad women, mad world : the depiction of madness in Renaissance drama. Those crazy Scots : madness and transformation in the ballad tradition of Scotland Amy C. O'Brien Lehigh University Follow this and additional works at: http://preserve.lehigh.edu/etd Recommended Citation O'Brien, Amy C., "Mad women, mad world : the depiction of madness in Renaissance drama. Those crazy Scots : madness and transformation in the ballad tradition of Scotland" (1994). Theses and Dissertations. Paper 265. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AUTHOR: O'Brien, Amy C. TITLE: Mad Women, Mad World: The Depiction of Madness " in Renaissance Drama- Those Crazy Scots: Madness and Transformation in the... DATE: May 29,1994 Mad Women, Mad World: the Depiction of Madness in Renaissance Drama Those Crazy Scots: , Madness and Transformation .t-- in the Ballad Tradition of Scotland by Amy C. O'Brien Presented to the Graduate and Research Committee of Lehigh University in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts in English Lehigh University 1994 r TABLE OF CONTENTS Mad Women, Mad World: A Discussion of Madness in Renaissance Drama Title Page and Abstract................•................1 Text 2 Those Crazy Scots: Madness and Transformation in the Ballad Tradition of Scotland TitIe Page and Abstract 36 Text 37 Notes 0 •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 57 Works Consulted ' ~ 59 Biography t•••••••••••• • 61 Mad Women, Mad World: the Depiction of Madness in Renaissance Drama An examination of madness in Renaissance England as reflected in historical accounts and in the period's drama. -

A Checklist of Child Ballad Variants Found in Southern Appalachia

A CHECKLIST OF CHILD BALLAD VARIANTS FOUND IN SOUTHERN APPALACHIA Thomas Burton and Ambrose Manning The following checklist—drawn from a considerable number of major published and unpublished sources, as well as selected minor ones—is a representative inventory of variants of Child ballads found in Southern Appalachia. It does not propose to be a definitive list. Nor does it overcome all the inherent limitations and problems confronting such an inventory; for example the difficulty in delineating “Southern Appalachia” (considered here as basically, but not exclusively, that area prescribed by the Appalachian Regional Commission) and the inability to consult the almost inexhaustible number of sources. We also had to accept such realities as the following: some sources include only one variant of a ballad, whereas other sources include representative variants of all the ones collected; collections sometimes designate, sometimes not, the specific place where a variant was recorded or from whom, but not necessarily where it was learned originally or other critical details of dissemination; some informants are included in multiple collections, and their songs are easily tallied, mistakenly, more than once; duplications can occur through the circumstance of multiple collectors recording from different members of the same family or from different persons who learned the same specific matrix; a collector may include the same variants in multiple collections without specifying whether they have been previously published; the credibility of variants can be dubious relative to a number of factors, including editorial policy; and fragments, summaries, written copies, oral traditional status, authenticity of sources, as well as other matters pose questions that are sometimes unfathomable and ultimately subjective. -

Tees Is Submitted in Partial Setiefaction for The

DEATH 11 an; BALLAD . TEES IS Subm i tt e d in Part i a l Set i e fa c t i on for the De gre e o f MASTER 93 LETTERS in the IVE TY L N UN RS I 93 CA IFOR IA . B y Agne s McDouge ll . Ma . y , 1 908 I B B L I O G B A. P H Y Al e n P i S u l , h lip ch yl e r t e Po a P S ud i s in pul r o e try . Un e s Chi c a o P s s 1 9 iv r i ty o f g re , 03 . m s W am ( Ed . ) Ar e , i l l i Dall am d E ad an d Ol ngl i sh B al l s Fo lk Songs . Macm a C om an 1 04 . i l l n p y , 9 c a Ed . Chi ld , Fran i s J me s ( ) d P B a Engl i sh an Sc o t t i sh opul ar all d s . Ho ht on M i C om an 1 898 . us , i ffl n p y , ‘ C ou t l r e n ay , . L . The Ide a o f T rage dy . We s m s e 1 t in t r , 900 . Ca a e s M s yl ey , Ch rl i l l M C e r t and art in . Flah y t e P Po e try o f h e op l e . -

Incest in Ballads: the Availability of Cultural Meaning EBEOGU, AFAM N

Lore and Language The Journal of the Centre for English Cultural Tradition and Language Editor J.D.A. Widdowson Centre for English Cultural Tradition and Language, University of Sheffield Editorial Board N .F . Blake, University of Sheffield D.O. Buchan, Memorial University of Newfoundland G . Cox, University of Reading D .G. Hey, University of Sheffield J.M. Kirk, The Queen ·s University of Belfast R . L e ith, Leamington Spa C. Neilands, The Queen's University of Belfast P .S. Smith, Memorial University of Newfoundland © 1993 Hisarlik Press. Apart fro1n any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticis1n or review, as pennitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, or where reproduction is required for classroon1 use or coursework by students, this publication 1nay only be reproduced, stored or trans1nitted, in any fonn or by any tneans, with the prior pennission in writing of the publishers. US copyright law applicable to users in the USA. Lore and Language is published twice annually, in January and July. Volutne 11 is a single vol mne ( cotnprising two issues) covering two years, 1992-1993; Volutne 12 will cover 1994. Subscription rates for Volutne 11 are: Institutional, £50.00; Personal, £12 (all prices in Sterling). Send pay1nent to Hisarlik Press, 4 Catisfield Road, Enfield Lock, Middlesex EN3 6BD, UK, or credit card details to Vine House Distribution, Waldenbury, North Cointnon, Chailey, East Sussex BNg 4DR, UK. All other business correspondence concerning Volutne 11 and later volutnes should be addressed to Hisarlik Press, 4 Catisfield Road, Enfield Lock, Middlesex EN3 6BD, UK; tel.