Nicol, Scott, and the Ballad Collectors DAVID D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INTERPRETING POETRY: English and Scottish Folk Ballads (Year 5, Day Department, 2016) Assignments for Self-Study (25 Points)

The elective discipline «INTERPRETING POETRY: English and Scottish Folk Ballads (Year 5, day department, 2016) Assignments for Self-Study (25 points) Task: Select one British folk ballad from the list below, write your name, perform your individual scientific research paper in writing according to the given scheme and hand your work in to the teacher: Titles of British Folk Ballads Students’ Surnames 1. № 58: “Sir Patrick Spens” 2. № 13: “Edward” 3. № 84: “Bonny Barbara Allen” 4. № 12: “Lord Randal” 5. № 169:“Johnie Armstrong” 6. № 243: “James Harris” / “The Daemon Lover” 7. № 173: “Mary Hamilton” 8. № 94: “Young Waters” 9. № 73:“Lord Thomas and Annet” 10. № 95:“The Maid Freed from Gallows” 11. № 162: “The Hunting of the Cheviot” 12. № 157 “Gude Wallace” 13. № 161: “The Battle of Otterburn” 14. № 54: “The Cherry-Tree Carol” 15. № 55: “The Carnal and the Crane” 16. № 65: “Lady Maisry” 17. № 77: “Sweet William's Ghost” 18. № 185: “Dick o the Cow” 19. № 186: “Kinmont Willie” 20. № 187: “Jock o the Side” 21. №192: “The Lochmaben Harper” 22. № 210: “Bonnie James Campbell” 23. № 37 “Thomas The Rhymer” 24. № 178: “Captain Car, or, Edom o Gordon” 25. № 275: “Get Up and Bar the Door” 26. № 278: “The Farmer's Curst Wife” 27. № 279: “The Jolly Beggar” 28. № 167: “Sir Andrew Barton” 29. № 286: “The Sweet Trinity” / “The Golden Vanity” 30. № 1: “Riddles Wisely Expounded” 31. № 31: “The Marriage of Sir Gawain” 32. № 154: “A True Tale of Robin Hood” N.B. You can find the text of the selected British folk ballad in the five-volume edition “The English and Scottish Popular Ballads: five volumes / [edited by Francis James Child]. -

Love Tokens in the Lai De L'ombre Barry O'neill Center For

Love Tokens in the Lai de l’Ombre Barry O’Neill Center for International Security and Cooperation Stanford University [email protected] UCLA Conference on Political Games in the Middle Ages March 2001 DRAFT ABSTRACT: The thirteenth century poem, Lai de l’Ombre, or “lay of the shadow,” tells of a knight stricken with lovesickness for a married lady whom he has seen but never met. He visits her to persuade her to accept him as her lover, or at least to take his ring as a token. She refutes all his reasons, but just when she seems to have won the argument, he uses the ring to make a surprising move, showing her his courtly skill and capturing her love. One question is why his move is so clever, but a broader one is why their dispute focuses on the ring. This paper presents a theory concerning the basis of love tokens such as rings, anniversary dinners or Valentine’s gifts. The basis of the theory is how one person’s emotion responds to the perception of a reciprocal emotion in another. One signficance of the theory is that it combines the strategic and emotional aspects of action. Acknowledgements: I would like to thank Ned Duval, Jacques Hyman, Kimberly Theidon, Scott Waugh and Patience Young for their help and very useful suggestions. Support from the Center for International Security and Cooperation is appreciated. 2 The Lay of the Shadow, written in Old French about 1220 A.D., tells how a knight is smitten with a certain married lady, argues with her to persuade her to accept him, and, when it seems he has lost his case, how he pulls a clever trick, using her reflection, or “shadow,” on the surface of a well (Renart, Orr, ed., 1948; translated Goodrich, 1964, reproduced below in Appendix II.) The poet, who identifies himself in the final lines as “Jehan Renart,” crafted a delicate story that combines ideas of courtly love dialogues with a full plot as in the Breton lays, and to a lesser extent seduction tricks of the fabliaux. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G. Phd, Mphil, Dclinpsychol) at the University of Edinburgh

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Desire for Perpetuation: Fairy Writing and Re-creation of National Identity in the Narratives of Walter Scott, John Black, James Hogg and Andrew Lang Yuki Yoshino A Thesis Submitted to The University of Edinburgh for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English Literature 2013 Abstract This thesis argues that ‘fairy writing’ in the nineteenth-century Scottish literature serves as a peculiar site which accommodates various, often ambiguous and subversive, responses to the processes of constructing new national identities occurring in, and outwith, post-union Scotland. It contends that a pathetic sense of loss, emptiness and absence, together with strong preoccupations with the land, and a desire to perpetuate the nation which has become state-less, commonly underpin the wide variety of fairy writings by Walter Scott, John Black, James Hogg and Andrew Lang. -

Introduction

Introduction anne grImes had a gift for collecting songs—partly because she knew how and where to find them. “Everybody thinks you find folk music in the hills; you don’t . it’s in people’s heads,” she told a reporter for the Columbus Citizen- Journal in 1971 before performing at Governor John Gilligan’s Inau- gural Gala at the Ohio Theater in Columbus, Ohio. Born into a pio- neer Ohio family in which music had been important over the gen- erations, Anne Grimes felt a kin- ship with the traditional singers she discovered. As she told the reporter: “In the folk music field, the technical term is ‘informants’; I prefer to think of the people as contributors.” During the height of her col- lecting and performing career in the 1950s and early 1960s, Anne Grimes sang several times at the The cover of the Columbus Dispatch Sunday Magazine, annual National Folk Festival February 17, 1952: Anne Grimes and recorded on Folkways. She with her five children—Mindy also became an expert in the lore (2), Mary (4), Jennifer (6), Sara and techniques of the plucked (10), and Steve (12)—in front or lap dulcimer (also referred to of the Jonathan Alder cabin as the mountain or Appalachian west of Columbus. Photo by Dan F. Prugh courtesy of the dulcimer), and the Anne Grimes Columbus Dispatch collection of these rare folk in- struments—now housed at the Smithsonian Institution—ranks among the nation’s finest. But much of her time and energy was devoted to collecting hundreds of songs and ballads that she then performed in concert-lectures with the general theme of Ohio history through song. -

Ancient Ballads and Songs of the North of Scotland, Hitherto

1 ifl ANCIENT OF THE NOETH OF SCOTLAND, HITHERTO UNPUBLISHED. explanatory notes, By peter BUCHAN, COKRESFONDING ME3IBER OF THE SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES OF SCOTLAND. " The ancient spirit is not dead,— " Old times, wc trust, are living here.' VOL. ir. EDINBURGH: PRINTED 1011 W. & D. LAING, ANI> J, STEVENSON ; A. BllOWN & CO. ABERDEEN ; J. WYLIE, AND ROBERTSON AND ATKINSON, GLASGOW; D. MORISON & CO. PERTH ; AND J. DARLING, LONDON. MDCCCXXVIII. j^^nterct! in -Stationers i^all*] TK CONTENTS V.'Z OF THK SECOND VOLUME. Ballads. N'olcs. The Birth of Robin Hood Page 1 305 /King Malcolm and Sir Colvin 6 30G Young Allan - - - - 11 ib. Sir Niel and Mac Van 16 307 Lord John's Murder 20 ib. The Duke of Athole's Nurse 23 ib. The Laird of Southland's Courtship 27 308 Burd Helen ... 30 ib. Lord Livingston ... 39 ib. Fause Sir John and IMay Colvin 45 309 Willie's Lyke Wake 61 310 JSTathaniel Gordon - - 54 ib. Lord Lundy ... 57 312 Jock and Tarn Gordon 61 ib. The Bonny Lass o' Englessie's Dance 63 313 Geordie Downie . - 65 314 Lord Aboyne . 66 ib. Young Hastings ... 67 315 Reedisdale and Wise William 70 ib. Young Bearwell ... 75 316 Kemp Owyne . 78 ib. Earl Richard, the Queen's Brother 81 318 Earl Lithgow .... 91 ib. Bonny Lizie Lindsay ... 102 ib. The Baron turned Ploughman 109 319 Donald M'Queen's Flight wi' Lizie Menzie 117 ib. The Millar's Son - - - - 120 320 The Last Guid-night ... 127 ib. The Bonny Bows o' London 128 ib. The Abashed Knight 131 321 Lord Salton and Auchanachie 133 ib. -

The Ballad/Alan Bold Methuen & Co

In the same series Tragedy Clifford Leech Romanticism Lilian R Furst Aestheticism R. V. Johnson The Conceit K. K Ruthven The Ballad/Alan Bold The Absurd Arnold P. Hinchliffe Fancy and Imagination R. L. Brett Satire Arthur Pollard Metre, Rhyme and Free Verse G. S. Fraser Realism Damian Grant The Romance Gillian Beer Drama and the Dramatic S W. Dawson Plot Elizabeth Dipple Irony D. C Muecke Allegory John MacQueen Pastoral P. V. Marinelli Symbolism Charles Chadwick The Epic Paul Merchant Naturalism Lilian R. Furst and Peter N. Skrine Rhetoric Peter Dixon Primitivism Michael Bell Comedy Moelwyn Merchant Burlesque John D- Jump Dada and Surrealism C. W. E. Bigsby The Grotesque Philip Thomson Metaphor Terence Hawkes The Sonnet John Fuller Classicism Dominique Secretan Melodrama James Smith Expressionism R. S. Furness The Ode John D. Jump Myth R K. Ruthven Modernism Peter Faulkner The Picaresque Harry Sieber Biography Alan Shelston Dramatic Monologue Alan Sinfield Modern Verse Drama Arnold P- Hinchliffe The Short Story Ian Reid The Stanza Ernst Haublein Farce Jessica Milner Davis Comedy of Manners David L. Hirst Methuen & Co Ltd 19-+9 xaverslty. Librasü Style of the ballads 21 is the result not of a literary progression of innovators and their acolytes but of the evolution of a form that could be men- 2 tally absorbed by practitioners of an oral idiom made for the memory. To survive, the ballad had to have a repertoire of mnemonic devices. Ballad singers knew not one but a whole Style of the ballads host of ballads (Mrs Brown of Falkland knew thirty-three separate ballads). -

A Collection of Ballads

A COLLECTION OF BALLADS INTRODUCTION When the learned first gave serious attention to popular ballads, from the time of Percy to that of Scott, they laboured under certain disabilities. The Comparative Method was scarcely understood, and was little practised. Editors were content to study the ballads of their own countryside, or, at most, of Great Britain. Teutonic and Northern parallels to our ballads were then adduced, as by Scott and Jamieson. It was later that the ballads of Europe, from the Faroes to Modern Greece, were compared with our own, with European Märchen, or children’s tales, and with the popular songs, dances, and traditions of classical and savage peoples. The results of this more recent comparison may be briefly stated. Poetry begins, as Aristotle says, in improvisation. Every man is his own poet, and, in moments of stronge motion, expresses himself in song. A typical example is the Song of Lamech in Genesis— “I have slain a man to my wounding, And a young man to my hurt.” Instances perpetually occur in the Sagas: Grettir, Egil, Skarphedin, are always singing. In Kidnapped, Mr. Stevenson introduces “The Song of the Sword of Alan,” a fine example of Celtic practice: words and air are beaten out together, in the heat of victory. In the same way, the women sang improvised dirges, like Helen; lullabies, like the lullaby of Danae in Simonides, and flower songs, as in modern Italy. Every function of life, war, agriculture, the chase, had its appropriate magical and mimetic dance and song, as in Finland, among Red Indians, and among Australian blacks. -

MJ06-National Copy.Indd

Vita-final 4/7/06 4:44 PM Page 52 VITA Francis James Child Brief life of a Victorian enthusiast: 1825-1896 by john burgess rancis james child, a.b. 1846, was a model of nineteenth- and their American and Canadian variants. That demanded pa- century academic achievement. Named Harvard’s Boylston tience in tracking manuscripts across continents, judgment in in- professor of rhetoric and oratory at 26, he was one of his terpreting and clarifying textual discrepancies, and persistence in Fcentury’s leading Chaucer scholars and received honorary degrees dealing with collectors ranging from the high-born Lord Rose- from his alma mater, Columbia, and Göttingen. His close friends bery to the eccentric Devon clergyman Sabine Baring-Gould. included Oliver Wendell Holmes, Henry and William James, and In all, Child collected 305 ballads, ultimately published in five Charles Eliot Norton. Yet today he is better remembered than volumes (1882-98), including “Lord Randall,” “Sir Patrick Spens,” many distinguished colleagues because, at the height of his career, and a good three dozen variations on the adventures of Robin he decided to apply a gift for scholarship honed on the study of Hood. Some, like “Barbara Allen,” had been in print for generations traditional literature to the oral traditions of the folk ballad. and were sung from London to Appalachia. Others, like “Thomas That a sailmaker’s son achieved eminence of any sort was large- the Rhymer” or “Tam Lin,” evoke a world of magic that survived ly because the Boston of his youth was progressive enough to o≠er outside the written record for centuries. -

The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, Vol 1 the English and Scottish Popular Ballads, Vol 1

(Online library) The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, Vol 1 The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, Vol 1 n8wDVwc0h The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, Vol 1 SsvC23BOY JB-94841 oNOJiw1Kx US/Data/Literature-Fiction RikWgV4bZ 4/5 From 380 Reviews TucVlMW5A Francis James Child LtjZMbxxY DOC | *audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF | ePub TucVlMW5A j51rurhwh oS25p5n4i VMw5zHxzB CxflSTCQY EU4pO0673 5n4SWKc2S BLQtDiSDj 9 of 9 people found the following review helpful. Excellent "corrected" KWJG5tsuI editionBy J. R. BrownChild's "English and Scottish Popular Ballads" is THE M3bkUU5Yw sourcebook for anyone interested in the traditional ballads of the British Isles, iGmA1vIMo and also invaluable to all aficionados of European folklore and folksong in gfPsfjA3w general. For those not up on their terminology, a ballad is a folksong with a kF5zpAkfS plot, and Child's collection covers everything from foul murders to star-crossed vIZARObwI lovers to Robin Hood, in five volumes.I am extremely happy that someone has ObBtBRj1v finally issued an edition incorporating the various addenda and corrections that uL7kEYlKV Child made before his death. There is nothing here that Child did not write, so ZtO3hRPBj if you are looking for additional scholarship or commentary you will be sK2ucgFK4 disappointed; but the Loomis House edition vastly improves over the Dover tM2LJk6P5 facsimiles in completeness and convenience. Additional variants, comments and bgoCI04Of even some tunes (the one big omission in the original) are placed conveniently 8Jms2TZ2e near -

Table ID Book Titile Song Title 4

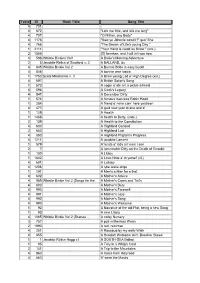

Table ID Book Titile Song Title 4 701 - 4 672 "Lo'e me little, and lo'e me lang" 4 707 "O Mither, ony Body" 4 1176 "Saw ye Johnnie comin'?" quo' She 4 766 "The Dream of Life's young Day " 1 2111 "Your Hand is cauld as Snaw " (xxx.) 2 1555 [O] hearken, and I will tell you how 4 596 Whistle Binkies Vol1 A Bailie's Morning Adventure 2 5 Jacobite Relics of Scotland v. 2 A BALLAND, &c 4 845 Whistle Binkie Vol 2 A Bonnie Bride is easy buskit 4 846 A bonnie wee lassie 1 1753 Scots Minstrelsie v. 3 A Braw young Lad o' High Degree (xxi.) 4 597 A British Sailor's Song 1 573 A cogie o' ale an' a pickle aitmeal 4 598 A Cook's Legacy 4 847 A December Dirty 1 574 A famous man was Robin Hood 1 284 A friend o' mine cam' here yestreen 4 477 A guid new year to ane and a' 1 129 A Health 1 1468 A health to Betty, (note,) 2 139 A Health to the Constitution 4 600 A Highland Garland 2 653 A Highland Lad 4 850 A Highland Pilgram's Progress 4 1211 A jacobite Lament 1 579 A' kinds o' lads an' men I see 2 7 A lamentable Ditty on the Death of Geordie 1 130 A Litany 1 1842 A Love-Note a' to yersel' (xi.) 4 601 A Lullaby 4 1206 A lyke wake dirge 1 291 A Man's a Man for a that 4 602 A Mother's Advice 4 989 Whistle Binkie Vol 2 (Songs for the A Mother's Cares and Toil's 4 603 Nursery) A Mother's Duty 4 990 A Mother's Farewell 4 991 A Mother's Joys 4 992 A Mother's Song 4 993 A Mother's Welcome 1 92 A Narrative of the old Plot; being a new Song 1 93 A new Litany 4 1065 Whistle Binkie Vol 2 (Scenes … A noisy Nursery 3 757 Nursery) A puir mitherless Wean 2 1990 A red, red rose 4 251 A Rosebud by my early Walk 4 855 A Scottish Welcome to H. -

Ballad of the Month: Lamkin (Child #93)

34 Lamkin (Child #93) Editor: The gruesome tale of the wronged stonemason entering the castle of the greedy nobleman and extracting his revenge by murdering the nobleman's wife and baby with the help of the nurse is one I've been reluctant to sing. Not being one to shy away from the usual tabloid exploits of the Child ballad, with their rapes, murders, infanticide, and incest, I am at a loss to explain my reluctance. So it is with pleasure that I welcome Jon Bartlett and Rika Ruebsaat's discussion of this ballad. After reading their discussion and hearing Northwest Territory balladeer Moira Cameron sing it, I'm ready to tackle it. Almost. It's Lamkin was a masongood As everbuilt wi' stane, He built Lord Wearie'scastle But payment he got nane. But the nourice was a fause limmer As e'er hung on a tree,' She laid a plot wi' Lamkin, Whanher lord was o'er the sea. She laid a plot wi' Lamkin, Whenthe servantswere awa' Loot him in at a little shot-window And brought him to the ha '. "Oh whare's the lady 0' this house That ca's me Lamkin?" "She'sup in her bowersewing But we sooncan bring her down. Then Lamkin's ta 'en a sharp knife That hung down by his gair And he has gien the bonny babe A deepwound and a sair. Then Lamkin he rocked, And the fause nourice sang Till frae ilka bore0 ' the cradle The red blood out sprang. "Oh still my bairn, nourice, Oh still him wi' the pap!" "He winna still, lady, For this nor for that." "Oh still my bairn, nourice, Oh still him wi' the bell!" "He winna still, lady, Till ye c;omedown yoursel." Oh the {irsten step shesteppit She steppit on a stane; But the neistenstep shesteppit She met him -- Lamkin. -

Mcalpine (1995)

ýýesi. s ayoS THE GALLOWS AND THE STAKE: A CONSIDERATION OF FACT AND FICTION IN THE SCOTTISH BALLADS FOR MY PARENTS AND IN MEMORY OF NAN ANDERSON, WHO ALMOST SAW THIS COMPLETED iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Before embarking on the subject of hanging and burning, I would like to linger for a moment on a much more pleasant topic and to take this opportunity to thank everyone who has helped me in the course of my research. Primarily, thanks goes to all my supervisors, most especially to Emily Lyle of the School of Scottish Studies and to Douglas Mack of Stirling, for their support, their willingness to read through what must have seemed like an interminable catalogue of death and destruction, and most of all for their patience. I also extend thanks to Donald Low and Valerie Allen, who supervised the early stages of this study. Three other people whom I would like to take this opportunity to thank are John Morris, Brian Moffat and Stuart Allan. John Morris provided invaluable insight into Scottish printed balladry and I thank him for showing the Roseberry Collection to me, especially'The Last Words of James Mackpherson Murderer'. Brian Moffat, armourer and ordnancer, was a fount of knowledge on Border raiding tactics and historical matters of the Scottish Middle and West Marches and was happy to explain the smallest points of geographic location - for which I am grateful: anyone who has been on the Border moors in less than clement weather will understand. Stuart Allan of the Historic Search Room, General Register House, also deserves thanks for locating various documents and papers for me and for bringing others to my attention: in being 'one step ahead', he reduced my workload as well as his own.