Insights from Research on Dunbar High School

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

22206 18Th Street Flyer

Washington, DC 10 Minute Drive Time Crestwood Melvin Hazen Park The Catholic University of America McLean Gardens American University Po rte r S tr ee t N W Old Soldiers’ Home Golf Course Mount Pleasant Smithsonian National Zoological Columbia Heights MedStar M Cathedral Heights a Park Washington ss ac h C u Hospital s o e n tt n Center s e A c v t e i n c u u e t Woodley Park N A W v e n u Rock Creek e N Park Glover W Howard Archbold Park University United States Naval Observatory Adams F Glover Park o x Morgan h a l l R o a d N W W N e Bloomingdale nu ve A a rid Kalorama lo W Burleith F N e u n e v A e ir Eckington h s Reservoir Road p m Shaw a 1 H 6 t w h e N S t r e e t Foxhall Logan Circle Truxton Circle M Georgetown E a NW N cArt ue ue hur en ven Bl Av A vd Dupont Circle nd ork sla Y e I ew od N Rh Can al Road NW M Street West End Mount Vernon Square Downtown Wa K Street shington Memorial Parkway 7 t W h e N S nu t ve r A e ork e w Y t Chinatown Ne Penn Quarter Residential RosslynTotal Average Daytime Population Households Household Population Judiciary Square Income The White House 161,743 85,992 $134,445 344,027 Wells Fargo Bank Star Trading Starbucks Osteria Al Volo W N Epic Philly Steaks Neighborhood some of DC’s liveliestnightspots. -

District Columbia

PUBLIC EDUCATION FACILITIES MASTER PLAN for the Appendices B - I DISTRICT of COLUMBIA AYERS SAINT GROSS ARCHITECTS + PLANNERS | FIELDNG NAIR INTERNATIONAL TABLE OF CONTENTS APPENDIX A: School Listing (See Master Plan) APPENDIX B: DCPS and Charter Schools Listing By Neighborhood Cluster ..................................... 1 APPENDIX C: Complete Enrollment, Capacity and Utilization Study ............................................... 7 APPENDIX D: Complete Population and Enrollment Forecast Study ............................................... 29 APPENDIX E: Demographic Analysis ................................................................................................ 51 APPENDIX F: Cluster Demographic Summary .................................................................................. 63 APPENDIX G: Complete Facility Condition, Quality and Efficacy Study ............................................ 157 APPENDIX H: DCPS Educational Facilities Effectiveness Instrument (EFEI) ...................................... 195 APPENDIX I: Neighborhood Attendance Participation .................................................................... 311 Cover Photograph: Capital City Public Charter School by Drew Angerer APPENDIX B: DCPS AND CHARTER SCHOOLS LISTING BY NEIGHBORHOOD CLUSTER Cluster Cluster Name DCPS Schools PCS Schools Number • Oyster-Adams Bilingual School (Adams) Kalorama Heights, Adams (Lower) 1 • Education Strengthens Families (Esf) PCS Morgan, Lanier Heights • H.D. Cooke Elementary School • Marie Reed Elementary School -

Compiled Public Comments Wednesday, August 7 | Mt

PHASE 2 COMPILED PUBLIC COMMENTS WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 7 | MT. PLEASANT LIBRARY 1 WORKBOOK COMMENTS Staff did their best to transcribe all handwritten comments. Originals are available upon request at the offices of the National Capital Planning Commission. Frederic Harwood | Shaw, DC Approach 1: Leaves the skyline looking like a pancake with a pencil sticking out of it. Limits the city’s economic growth, jobs, retail. Limits the development of the “creative city,” a place where creative people meet, interact, cross‐fertilize to create technology, ideas, the future. Limits taxes to help lower income residents—taxes from increased densities of professionals and creative types generate tax revenue to build schools, recreation, and low income housing. Approach 2: The relationship of height to streeth width is irrelevant. Philadelphia has 1,000 foot tall buildings in 2 & 3 lane streets (40‐60 feet). What matters is the quality of what goes on at street level—restaurants, retail, theaters, open spaces, plazas—not how high the buildings are. We are over‐planning and over‐engineering the building heights. New York, Philadelphia, Boston, Chicago, do not tie building height to street width—put something interesting on the street and building heights will be irrelevant. Approach 3: Yes to all three. Eliminating height limits would especially benefit under‐developed areas such as Benning Road, Anacostia—where the economic benefits of high commercial towers would trickle into the surrounding neighborhoods and provide jobs, both professional and service jobs. L’Enfant city would benefit because it is nearly 100% built out and economic growth stagnating. The bowl outside L’Enfant city would benefit with housing, people, residents who would support retail, creating creative jobs, and pay income and real estate taxes to benefit all residents. -

Housing in the Nation's Capital

Housing in the Nation’s2005 Capital Foreword . 2 About the Authors. 4 Acknowledgments. 4 Executive Summary . 5 Introduction. 12 Chapter 1 City Revitalization and Regional Context . 15 Chapter 2 Contrasts Across the District’s Neighborhoods . 20 Chapter 3 Homeownership Out of Reach. 29 Chapter 4 Narrowing Rental Options. 35 Chapter 5 Closing the Gap . 43 Endnotes . 53 References . 56 Appendices . 57 Prepared for the Fannie Mae Foundation by the Urban Institute Margery Austin Turner G. Thomas Kingsley Kathryn L. S. Pettit Jessica Cigna Michael Eiseman HOUSING IN THE NATION’S CAPITAL 2005 Foreword Last year’s Housing in the Nation’s Capital These trends provide cause for celebration. adopted a regional perspective to illuminate the The District stands at the center of what is housing affordability challenges confronting arguably the nation’s strongest regional econ- Washington, D.C. The report showed that the omy, and the city’s housing market is sizzling. region’s strong but geographically unbalanced But these facts mask a much more somber growth is fueling sprawl, degrading the envi- reality, one of mounting hardship and declining ronment, and — most ominously — straining opportunity for many District families. Home the capacity of working families to find homes price escalation is squeezing families — espe- they can afford. The report provided a portrait cially minority and working families — out of of a region under stress, struggling against the city’s housing market. Between 2000 and forces with the potential to do real harm to 2003, the share of minority home buyers in the the quality of life throughout the Washington District fell from 43 percent to 37 percent. -

Collections Survey FY 2017 Report and Preliminary Finding Guide

Collections Survey FY 2017 Report and Preliminary Finding Guide DC Oral History Collaborative A project of Humanities DC and the Historical Society of Washington, D.C. for The District of Columbia Public Library Contract No. DCPL-2017-C-0008 Prepared by Anna F. Kaplan Oral History Project Surveyor, DC Oral History Collaborative August 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction, Scope and Purpose………………………………………………………………………….. 2 Methodology …………………………………………….…………………………………………………………. 4 List of Repositories Surveyed and Abberviations.………………………………………………….. 5 Map of Repository Locations ……………………………………………………………….……………….. 6 Summary of Findings at Each Repository ……………………………………………………………… 7 Repository Contact Information ……………………………………………………………….………... 17 Repositories Contacted with No Response ……………………………………………………..…… 21 Additional Repositories to Approach in the Future ………………………………………….….. 21 Organizations Currently Conducting Oral Histories …………………………………………..... 22 Index of Narrator Names with Repository Locations …………………………………………… 23 Acknowledgments …………………………………………………………………………………………….... 67 1 INTRODUCTION The DC Oral History Collaborative is an ambitious city-wide initiative to document and preserve the history of Washington’s residents and communities through the collection of oral histories. The project will survey and publicize existing oral history collections, provide grants and training for scholars and amateur historians to launch new oral history projects, and establish an interactive, accessible platform where the city’s memories can benefit residents and scholars for generations to come. Origins of the DC Oral History Collaborative In 2016 D.C. Councilmember David Grosso expressed an interest in helping the citizens of Washington, D.C. gain access to hundreds of oral histories that illuminate our shared history but are difficult to find. In addition, having seen initiatives underway in other cities, the councilmember wanted to encourage the collection of new oral histories from elders and others whose stories need to be told and recorded for future generations. -

State of Washington, D.C.'S Neighborhoods A-3

State of Washington, D.C.’s Neighborhoods Prepared by Peter A. Tatian G. Thomas Kingsley Margery Austin Turner Jennifer Comey Randy Rosso Prepared for The Office of Planning The Government of the District of Columbia September 30, 2008 The Urban Institute 2100 M Street, NW Washington, DC 20037 UI project no. 08040-000-01 State of Washington, D.C.’s Neighborhoods ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ............................................................................................... ii Acknowledgments............................................................................................. vi About this Report ............................................................................................... 1 I. Introduction...................................................................................................... 3 II. Demographics................................................................................................. 9 Population......................................................................................................................9 Households..................................................................................................................13 III. Economy – Jobs and Income ..................................................................... 15 Employed Residents and Unemployment Rate...........................................................15 Poverty and Household Income ..................................................................................18 Public Assistance -

Neighborhood Cluster (NC)

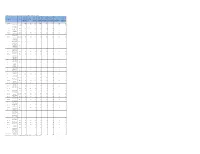

2014 Population Projections and Growth (between 2014 to 2020) by Neighborhood Cluster Office of Office of Office of % change in projected % change in projected % change in projected % change in projected Office of Planning's Planning's Planning's Planning's number of 0-3 year number of number of number of 14-17 year Neighborhood Cluster Population Cluster Names Ward Population Population Population olds per 4-10 year olds per 11-13 year olds per olds per (NC) Forecast in 2014 Forecast in 2014 Forecast in 2014 Forecast in 2014 neighborhood cluster neighborhood cluster neighborhood cluster neighborhood cluster (Ages 4-10) (Ages 0-3) (Ages 11-13) (Ages 14-17) 2014_2020 2014_2020 2014_2020 2014_2020 Citywide 36,910 44,227 15,577 20,296 12% 47% 32% 12% Kalorama Heights, Cluster 1 Adams Morgan and Ward1 & 2 981 752 179 181 18% 136% 98% 50% Columbia Heights, Mt. Pleasant, Pleasant Cluster 2 Plains and Park View Ward 1 3,506 3,267 1,044 1,251 -1% 78% 45% 27% Howard University, Le Droit Park and Cluster 3 Cardozo/Shaw Ward 1,2 & 6 565 478 116 167 32% 120% 102% 6% Georgetown and Cluster 4 Burleith/Hillandale Ward 2 650 919 243 262 89% 39% 72% 47% West End, Foggy Cluster 5 Bottom, GWU Ward 2 350 213 30 23 161% 212% 207% 158% Dupont Circle and Connecticut Avenue/K Cluster 6 Street Ward 1 & 2 608 428 71 81 55% 169% 167% 65% Cluster 7 Shaw and Logan Circle Ward 2 & 6 958 890 262 316 15% 90% 58% 27% Downtown, Chinatown, Penn Quarters, Mount Vernon Square and Cluster 8 North Capitol Street Ward 2 & 6 876 967 300 371 24% 66% 66% 30% Southwest Employment -

Comprehensive Plan Near Northwest Area Element October 2019

Comprehensive Plan Near Northwest Area Element October 2019 Draft Amendments DELETIONS ADDITIONS CITATION HEADING CITATION Narrative Text. Citation NEW New text, policy, or action. CITATION Policy Element Abbreviation-Section Number. Policy Number: Policy Name CITATION Action Element Abbreviation-Section Number. Action Letter: Action Name Completed Action Text (at end of action and before citation): Completed – See Implementation Table. Chapter 21_Public_Review_Draft_NNW_Oct2019.docx Page 1 of 39 Comprehensive Plan Near Northwest Area Element October 2019 Draft Amendments Chapter 21_Public_Review_Draft_NNW_Oct2019.docx Page 2 of 39 Comprehensive Plan Near Northwest Area Element October 2019 Draft Amendments 2100 OVERVIEW 2100.1 The Near Northwest Planning Area encompasses the 3.69 square miles located directly north and west of Central Washington. It extends from Glover Archbold Park on the west to North Capitol Street on the east. Its northern boundary is formed by Whitehaven Parkway west of Rock Creek, and by Connecticut Avenue, U Street, and Florida Avenue east of Rock Creek. The southern boundary is formed by the Potomac River, the Central Employment Area, and New York Avenue (east of 7th Street). These boundaries are shown on the Map at left. Most of this area has historically been Ward 2, although in past and present times parts have also been included in Wards 1, and 5, and 6. 2100.1 2100.2 Near Northwest is known for its historic architecture, well-established neighborhoods, lively shopping areas, and nationally recognized institutions. These features provide enduring reminders of the city’s growth, from the 18th century to today’s international city. The Georgetown Historic District, established in 1950 in response to the demolition of large numbers of waterfront and canal-related historic buildings, was the first historic district established in the city. -

Washington DC Neighborhodd Trends Report 2013/14

CAPITAL 2013 /14’ MARKET WASHINGTON DC APPRAISAL NEIGHBORHOOD RESEARCH TRENDS DESK REPORT VOLUME 1, MARCH 2014 When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir. —John Maynard Keynes Contents 4 Introduction 4 Conventional, Conforming 30-Yr Fixed-Rate 4 Mortgage-Related Bond Issuance and Outstanding 6 The DC Market: One/ Five/ Ten-Year Relative Returns 7 DC Index vs. 10-City Composite Component Indices 7 Seasonality Index 7 Months of Inventory 10 Total Sales Volume and Financing Trends 11 Median Days on Market (DOM) 11 Distressed Sales 13 Parking 13 Market Value and Sales Volume 16 Washington DC: Neighborhood Trends 2013 16 Sales Volume Leaders 16 Market Cap Leaders 19 Median Sale Price 21 Median Sale to List Price 22 Median Days on Market 23 Distressed Sales 24 Neighborhood Databook 2013 30 Neighborhood Map 31 About Us 32 End Notes / General Disclaimer 1 202 320 3702 [email protected] 1125 11 St NW 402 WDC 20001 www.CapitalMarketAppraisal.com Introduction Mortgage-Related Bond Issuance and Outstanding he Capital Market Appraisal 2013 Neighborhood Trends Over the prior year residential mortgage-related bond is- Report was developed to provide market participants suance3 declined 7.6%, falling from $2.019 trillion in 2012 to with a comprehensive overview of the residential real $1.866 trillion in 2013. Over the same period of time resi- T 1 3 estate market in Washington, DC (DC Market ). dential mortgage-related bonds outstanding declined 1.04% from $8.179 trillion in 2012 to $8.094 trillion in 2013. As the We begin by highlighting a few broad measure—medium term overwhelming majority of residential mortgages are packaged trends in the mortgage market. -

Comprehensive Plan Mid-City Area Element October 2019

Comprehensive Plan Mid-City Area Element October 2019 Draft Amendments DELETIONS ADDITIONS CITATION HEADING CITATION Narrative Text. Citation NEW New text, policy, or action. CITATION Policy Element Abbreviation-Section Number.Policy Number: Policy Name CITATION Action Element Abbreviation-Section Number.Action Letter: Action Name Completed Action Text (at end of action and before citation): Completed – See Implementation Table. Page 1 of 47 3c03-07ac-df76-58da.docx Comprehensive Plan Mid-City Area Element October 2019 Draft Amendments 2000 OVERVIEW 2000 2000.1 The Mid-City Planning Area encompasses the 3.1 sQuare miles located in the geographic center of the District of Columbia. It extends from Rock Creek Park on the west to the CSX rail corridor on the east. Its southern edge is formed by Florida Avenue and U Street NW, and its northern edge is formed by Spring Road and Rock Creek Church Road. The boundaries are shown in the Map at left. Most of this area has historically been Ward 1 although the easternmost portion is currently part of Ward 5 and the southernmost portion is currently in Ward 2. 2000.1 3c03-07ac-df76-58da.docx Page 2 of 47 Comprehensive Plan Mid-City Area Element October 2019 Draft Amendments 2000.2 Mid-City is one of the most diverse parts of the city. Although it is one of the smallest of the ten planning areas geographically, it is the most populous and most dense. Much of the area was developed during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, giving it a rich and historic urban character. -

D.C.'S Disconnect Between Citywide Enrollment

D.C.’S DISCONNECT BETWEEN CITYWIDE ENROLLMENT GROWTH AND NEIGHBORHOOD CHANGES CHELSEA COFFIN | AUGUST 26, 2019 The District of Columbia has become a more popular place to live, especially for families. Population growth began in 2006, with young adults between the ages of 20 and 34 driving much of this growth (see Figure 1). This growth in the number of young adults translated into an increase in the number of babies born per year starting in 2006, and an increase in the school-age population starting in 2012. Figure 1. Population change driven by young adults and higher levels of births The school-age population (aged 5 to 17) started to rise a few years later in 2012, growing by 9 percent from 2010 to 2017.1 Public school2 enrollment for pre-kindergarten to grade 12 likewise grew by 20 percent over this time period. This population growth has also led to increased demand for family housing3 and rising property values: Citywide, the total assessed real value of single-family homes4 increased by 8.7 percent from 2010 to 2018, even while the total number of these homes decreased by 2.8 percent.5 1 Coffin, C. 2018. Will Children of Current Millennials Become Future Public School Students? D.C. Policy Center. Available at: https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/future-public-school-students-report/ 2 Here and throughout, public schools refer to both traditional public and public charter schools. 3 However, there is a lack of single-family apartments in D.C. See Tatian, P. A. and Hendley, L. 2019. -

State of Washington, D.C.'S Neighborhoods, 2010

2010 Prepared by Jennifer Comey Chris Narducci Peter A. Tatian Prepared for The Office of Planning The Government of the District of Columbia November 2010 The Urban Institute 2100 M Street, NW Washington, DC 20037 Copyright © November 2010. The Urban Institute. All rights reserved. Except for short quotes, no part of this report may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the Urban Institute. The Urban Institute is a nonprofit, nonpartisan policy research and educational organization that examines the social, economic, and governance problems facing the nation. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Urban Institute, its trustees, or its funders. State of Washington, D.C.’s Neighborhoods iii CONTENTS About this Report ............................................................................................... 1 I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 5 II. Demographics ................................................................................................. 7 Population ................................................................................................................... 7 Households ................................................................................................................12 III. Economy—Jobs and Income .....................................................................