Cultural Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cladding the Mid-Century Modern: Thin Stone Veneer-Faced Precast Concrete

CLADDING THE MID-CENTURY MODERN: THIN STONE VENEER-FACED PRECAST CONCRETE Sarah Sojung Yoon Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science in Historic Preservation Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation Columbia University May 2016 Advisor Dr. Theodore Prudon Adjunct Professor at Columbia University Principal, Prudon & Partners Reader Sidney Freedman Director, Architectural Precast Concrete Services Precast/ Prestressed Concrete Institute (PCI) Reader Kimball J. Beasley Senior Principal, Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc. (WJE) ABSTRACT Cladding the Mid-Century Modern: Thin Stone Veneer-Faced Precast Concrete Sarah Sojung Yoon Dr. Theodore Prudon, Advisor With significant advancements in building technology at the turn of the twentieth century, new building materials and innovative systems changed the conventions of construction and design. New materials were introduced and old materials continued to be transformed for new uses. With growing demand after WWII forcing further modernization and standardization and greater experimentation; adequate research and testing was not always pursued. Focusing on this specific composite cladding material consisting of thin stone veneer-faced precast concrete – the official name given at the time – this research aims to identify what drove the design and how did the initial design change over time. Design decisions and changes are evident from and identified by closely studying the industry and trade literature in the form of articles, handbooks/manuals, and guide specifications. For this cladding material, there are two major industries that came together: the precast concrete industry and the stone industry. Literature from both industries provide a comprehensive understanding of their exchange and collaboration. From the information in the trade literature, case studies using early forms of thin stone veneer-faced precast concrete are identified, and the performance of the material over time is discussed. -

OFFICIAL HOTELS Reserve Your Hotel for AUA2020 Annual Meeting May 15 - 18, 2020 | Walter E

AUA2020 Annual Meeting OFFICIAL HOTELS Reserve Your Hotel for AUA2020 Annual Meeting May 15 - 18, 2020 | Walter E. Washington Convention Center | Washington, DC HOTEL NAME RATES HOTEL NAME RATES Marriott Marquis Washington, D.C. 3 Night Min. $355 Kimpton George Hotel* $359 Renaissance Washington DC Dwntwn Hotel 3 Night Min. $343 Kimpton Hotel Monaco Washington DC* $379 Beacon Hotel and Corporate Quarters* $289 Kimpton Hotel Palomar Washington DC* $349 Cambria Suites Washington, D.C. Convention Center $319 Liaison Capitol Hill* $259 Canopy by Hilton Washington DC Embassy Row $369 Mandarin Oriental, Washington DC* $349 Canopy by Hilton Washington D.C. The Wharf* $279 Mason & Rook Hotel * $349 Capital Hilton* $343 Morrison - Clark Historic Hotel $349 Comfort Inn Convention - Resident Designated Hotel* $221 Moxy Washington, DC Downtown $309 Conrad Washington DC 3 Night Min $389 Park Hyatt Washington* $317 Courtyard Washington Downtown Convention Center $335 Phoenix Park Hotel* $324 Donovan Hotel* $349 Pod DC* $259 Eaton Hotel Washington DC* $359 Residence Inn Washington Capitol Hill/Navy Yard* $279 Embassy Suites by Hilton Washington DC Convention $348 Residence Inn Washington Downtown/Convention $345 Fairfield Inn & Suites Washington, DC/Downtown* $319 Residence Inn Downtown Resident Designated* $289 Fairmont Washington, DC* $319 Sofitel Lafayette Square Washington DC* $369 Grand Hyatt Washington 3 Night Min $355 The Darcy Washington DC* $296 Hamilton Hotel $319 The Embassy Row Hotel* $269 Hampton Inn Washington DC Convention 3 Night Min $319 The Fairfax at Embassy Row* $279 Henley Park Hotel 3 Night Min $349 The Madison, a Hilton Hotel* $339 Hilton Garden Inn Washington DC Downtown* $299 The Mayflower Hotel, Autograph Collection* $343 Hilton Garden Inn Washington/Georgetown* $299 The Melrose Hotel, Washington D.C.* $299 Hilton Washington DC National Mall* $315 The Ritz-Carlton Washington DC* $359 Holiday Inn Washington, DC - Capitol* $289 The St. -

Ravenel and Barclay 1610 and 1616 16Th Street NW | Washington, D.C

Ravenel and Barclay 1610 and 1616 16th Street NW | Washington, D.C. CORCORAN STREET NW Q STREET NW 16TH STREET NW OFFERING SUMMARY PROPERTY TOUR Property Visitation: Prospective purchasers will be afforded the opportunity to visit the Property during prescheduled tours. Tours will include access to a representative sample of units as well as common areas. To not disturb the Property’s ongoing operations, visitation requires advance notice and scheduling. Available Tour Dates: To schedule your tour of the Property, please contact Herbert Schwat at 202.618.3419 or [email protected]. Virtual tours are also available upon request. LEGAL DISCLAIMERS This Offering Summary is solely for the use of the purchaser. While the information contained in this Analysis has been compiled from sources we believe to be reliable, neither Greysteel nor its representatives make any representations or warranties as to the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in this Analysis. All financial information and projections are provided for reference only and are based on assumptions relating to the general economy, market conditions and other factors beyond our control. Purchaser is encouraged to conduct an independent due diligence investigation, prepare independent financial projections, and consult with their legal, tax and other professional advisors before making an investment decision. Greysteel does not have authority to legally bind the owner and no contract or agreement providing for any transaction shall be deemed to exist unless and until a final definitive contract has been executed and delivered by owner. All references to acreage, square footage, distance, and other measurements are approximations and must be independently verified. -

DC Archaeology Tour

WASHINGTON UNDERGROUND Archaeology in Downtown Washington DC A walking and metro guide to the past... 2003 ARCHAEOLOGY IN DC URBAN ARCHAEOLOGY IN OUR OWN BACKYARD (see Guide Map in the center of this brochure) Archaeology is the study of people’s lives through things they left behind. Although it’s not likely to be the first thing on the minds of most visitors to Washington, archaeologists have been active here for over a century. William Henry Holmes (1846-1933), curator of the U.S. National Museum (now the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History), profoundly influenced the scientific development of modern archaeology. In the DC area, Holmes conducted an extensive archaeological survey along the shores of the Potomac River, discovering numerous sites of the region’s earliest inhabitants. Interest in the ancient history of local American Indians has remained high since Holmes’ time. Archaeology of the development of the the city itself, or urban archaeology, got its start much more recently. In February of 1981, archaeologists spent several cold weeks inaugurating a new era of archaeology in DC, conducting excavations prior to construction of the old Civic Center at 9th and H Streets, NW. Since then, numerous archaeological excavations have been conducted in downtown Washington. Explore the locations of some of the archaeological findings in Washington’s historic commercial hub and learn about the things that lie under some of Washington’s oldest and newest buildings. HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE Each entry discusses a specific site or different aspect of Washington’s history that has been explored in archaeological excavations. -

7350 NBM Blueprnts/REV

MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Building in the Aftermath N AUGUST 29, HURRICANE KATRINA dialogue that can inform the processes by made landfall along the Gulf Coast of which professionals of all stripes will work Othe United States, and literally changed in unison to repair, restore, and, where the shape of our country. The change was not necessary, rebuild the communities and just geographical, but also economic, social, landscapes that have suffered unfathomable and emotional. As weeks have passed since destruction. the storm struck, and yet another fearsome I am sure that I speak for my hurricane, Rita, wreaked further damage colleagues in these cooperating agencies and on the same region, Americans have begun organizations when I say that we believe to come to terms with the human tragedy, good design and planning can not only lead and are now contemplating the daunting the affected region down the road to recov- question of what these events mean for the ery, but also help prevent—or at least miti- Chase W. Rynd future of communities both within the gate—similar catastrophes in the future. affected area and elsewhere. We hope to summon that legendary In the wake of the terrorist American ingenuity to overcome the physi- attacks on New York and Washington cal, political, and other hurdles that may in 2001, the National Building Museum stand in the way of meaningful recovery. initiated a series of public education pro- It seems self-evident to us that grams collectively titled Building in the the fundamental culture and urban char- Aftermath, conceived to help building and acter of New Orleans, one of the world’s design professionals, as well as the general great cities, must be preserved, revitalized, public, sort out the implications of those and protected. -

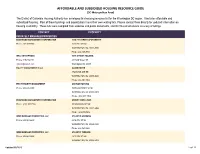

AFFORDABLE and SUBSIDIZED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE (DC Metropolitan Area)

AFFORDABLE AND SUBSIDIZED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE (DC Metropolitan Area) The District of Columbia Housing Authority has developed this housing resource list for the Washington DC region. It includes affordable and subsidized housing. Most of these buildings and organizations have their own waiting lists. Please contact them directly for updated information on housing availability. These lists were compiled from websites and public documents, and DCHA cannot ensure accuracy of listings. CONTACT PROPERTY PRIVATELY MANAGED PROPERTIES EDGEWOOD MANAGEMENT CORPORATION 1330 7TH STREET APARTMENTS Phone: 202-387-7558 1330 7TH ST NW WASHINGTON, DC 20001-3565 Phone: 202-387-7558 WEIL ENTERPRISES 54TH STREET HOUSING Phone: 919-734-1111 431 54th Street, SE [email protected] Washington, DC 20019 EQUITY MANAGEMENT II, LLC ALLEN HOUSE 3760 MINN AVE NE WASHINGTON, DC 20019-2600 Phone: 202-397-1862 FIRST PRIORITY MANAGEMENT ANCHOR HOUSING Phone: 202-635-5900 1609 LAWRENCE ST NE WASHINGTON, DC 20018-3802 Phone: (202) 635-5969 EDGEWOOD MANAGEMENT CORPORATION ASBURY DWELLINGS Phone: (202) 745-7334 1616 MARION ST NW WASHINGTON, DC 20001-3468 Phone: (202)745-7434 WINN MANAGED PROPERTIES, LLC ATLANTIC GARDENS Phone: 202-561-8600 4216 4TH ST SE WASHINGTON, DC 20032-3325 Phone: 202-561-8600 WINN MANAGED PROPERTIES, LLC ATLANTIC TERRACE Phone: 202-561-8600 4319 19th ST S.E. WASHINGTON, DC 20032-3203 Updated 07/2013 1 of 17 AFFORDABLE AND SUBSIDIZED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE (DC Metropolitan Area) CONTACT PROPERTY Phone: 202-561-8600 HORNING BROTHERS AZEEZE BATES (Central -

22206 18Th Street Flyer

Washington, DC 10 Minute Drive Time Crestwood Melvin Hazen Park The Catholic University of America McLean Gardens American University Po rte r S tr ee t N W Old Soldiers’ Home Golf Course Mount Pleasant Smithsonian National Zoological Columbia Heights MedStar M Cathedral Heights a Park Washington ss ac h C u Hospital s o e n tt n Center s e A c v t e i n c u u e t Woodley Park N A W v e n u Rock Creek e N Park Glover W Howard Archbold Park University United States Naval Observatory Adams F Glover Park o x Morgan h a l l R o a d N W W N e Bloomingdale nu ve A a rid Kalorama lo W Burleith F N e u n e v A e ir Eckington h s Reservoir Road p m Shaw a 1 H 6 t w h e N S t r e e t Foxhall Logan Circle Truxton Circle M Georgetown E a NW N cArt ue ue hur en ven Bl Av A vd Dupont Circle nd ork sla Y e I ew od N Rh Can al Road NW M Street West End Mount Vernon Square Downtown Wa K Street shington Memorial Parkway 7 t W h e N S nu t ve r A e ork e w Y t Chinatown Ne Penn Quarter Residential RosslynTotal Average Daytime Population Households Household Population Judiciary Square Income The White House 161,743 85,992 $134,445 344,027 Wells Fargo Bank Star Trading Starbucks Osteria Al Volo W N Epic Philly Steaks Neighborhood some of DC’s liveliestnightspots. -

International Business Guide

WASHINGTON, DC INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS GUIDE Contents 1 Welcome Letter — Mayor Muriel Bowser 2 Welcome Letter — DC Chamber of Commerce President & CEO Vincent Orange 3 Introduction 5 Why Washington, DC? 6 A Powerful Economy Infographic8 Awards and Recognition 9 Washington, DC — Demographics 11 Washington, DC — Economy 12 Federal Government 12 Retail and Federal Contractors 13 Real Estate and Construction 12 Professional and Business Services 13 Higher Education and Healthcare 12 Technology and Innovation 13 Creative Economy 12 Hospitality and Tourism 15 Washington, DC — An Obvious Choice For International Companies 16 The District — Map 19 Washington, DC — Wards 25 Establishing A Business in Washington, DC 25 Business Registration 27 Office Space 27 Permits and Licenses 27 Business and Professional Services 27 Finding Talent 27 Small Business Services 27 Taxes 27 Employment-related Visas 29 Business Resources 31 Business Incentives and Assistance 32 DC Government by the Letter / Acknowledgements D C C H A M B E R O F C O M M E R C E Dear Investor: Washington, DC, is a thriving global marketplace. With one of the most educated workforces in the country, stable economic growth, established research institutions, and a business-friendly government, it is no surprise the District of Columbia has experienced significant growth and transformation over the past decade. I am excited to present you with the second edition of the Washington, DC International Business Guide. This book highlights specific business justifications for expanding into the nation’s capital and guides foreign companies on how to establish a presence in Washington, DC. In these pages, you will find background on our strongest business sectors, economic indicators, and foreign direct investment trends. -

Washington, D.C Site Form

New York Avenue , NE Corridor, Washington, DC Florida Avenue NE & S. Dakota Avenue NE The New York Avenue NE Corridor is located northeast Any framework for this area should consider how to of Downtown. It stretches for approximately 3 miles reduce emissions and promote climate resilience between Florida Avenue NE and South Dakota Avenue while strengthening connectivity, walkability, and NE. It is a major auto-oriented gateway into the city, urban design transitions to adjacent communities and with approximately 100,000 vehicles moving through open space networks, as well as the racial and social the area every day and limited public transit options. equity conditions necessary for long-term social resilience. Robust and sustainable transportation, DC’s Mayor has set ambitious goals for more utility, and civic facility infrastructure, along with affordable housing, and development along the public amenities, are critical to unlocking the corridor could support them. The goal is to deliver as corridor’s full potential. many as 33,000 new housing units, with at least 1/3 of these being affordable. Regeneration should yield a For this site, students can choose to develop a high- vibrant residential and jobs-rich, low-carbon, mixed- level framework or masterplan for the entire site, use corridor. It should be inclusive of new affordable which may include some details on some more specific and market-rate housing units, supported by solutions, such as massing, open space and building sustainable infrastructure and community facilities. type studies. Or, students can choose to design a more detailed response for one or more of these Regeneration will need to preserve some of the subareas, (possibly working in coordinated teams so character and activity of the existing light industrial that all 3 subareas are covered):1: Union Market- (or PDR – Production, Distribution & Repair) uses. -

Important Travel Information

Important Travel Information Seminar Venue The Phillips Collection 1600 21st Street NW, Washington, D.C. 20009 202-387-2151 http://www.phillipscollection.org/ The Phillips Collection is accessible by Metrorail. Take the Red Line to Dupont Circle station and use the Q Street exit from the station. Once you exit the station, turn left (west) on to Q Street and walk one block to 21st Street NW. The museum is located near the corner of 21st and Q Street NW. Hotel Information The Fairfax at Embassy Row 2100 Massachusetts Avenue NW, Washington, D.C. 20008 (Two-minute walk from The Phillips Collection) 202-293-2100 http://fairfaxwashingtondc.com/ Note: Mention The Phillips Collection for a special room rate (202-835-2116) The Churchill Hotel 1914 Connecticut Avenue NW, Washington D.C. 20009 (Eight-minute walk from The Phillips Collection) 202-797-2000 http://www.thechurchillhotel.com/ Note: Mention The Phillips Collection for a special room rate Hotel Palomar 2121 P Street NW, Washington, D.C. 20037 (Four-minute walk from The Phillips Collection) 202-448-1800 http://www.hotelpalomar-dc.com/ The Dupont Circle Hotel 1500 New Hampshire Avenue NW, Washington, D.C. 20036 (Six-minute walk from The Phillips Collection) 202-483-6000 https://www.doylecollection.com/hotels/the-dupont-circle-hotel The Ritz Carlton, Washington, D.C. 1150 22nd Street NW, Washington, D.C. 20037 (Ten-minute walk from The Phillips Collection) 202-835-0500 http://www.ritzcarlton.com/en/Properties/WashingtonD.C./Default.htm Travel Information Washington-Metro Ronald Reagan Washington -

District Columbia

PUBLIC EDUCATION FACILITIES MASTER PLAN for the Appendices B - I DISTRICT of COLUMBIA AYERS SAINT GROSS ARCHITECTS + PLANNERS | FIELDNG NAIR INTERNATIONAL TABLE OF CONTENTS APPENDIX A: School Listing (See Master Plan) APPENDIX B: DCPS and Charter Schools Listing By Neighborhood Cluster ..................................... 1 APPENDIX C: Complete Enrollment, Capacity and Utilization Study ............................................... 7 APPENDIX D: Complete Population and Enrollment Forecast Study ............................................... 29 APPENDIX E: Demographic Analysis ................................................................................................ 51 APPENDIX F: Cluster Demographic Summary .................................................................................. 63 APPENDIX G: Complete Facility Condition, Quality and Efficacy Study ............................................ 157 APPENDIX H: DCPS Educational Facilities Effectiveness Instrument (EFEI) ...................................... 195 APPENDIX I: Neighborhood Attendance Participation .................................................................... 311 Cover Photograph: Capital City Public Charter School by Drew Angerer APPENDIX B: DCPS AND CHARTER SCHOOLS LISTING BY NEIGHBORHOOD CLUSTER Cluster Cluster Name DCPS Schools PCS Schools Number • Oyster-Adams Bilingual School (Adams) Kalorama Heights, Adams (Lower) 1 • Education Strengthens Families (Esf) PCS Morgan, Lanier Heights • H.D. Cooke Elementary School • Marie Reed Elementary School -

Mount-Vernon-Square-Brochure.Pdf

MOUNT VERNON SQUARE HISTORIC DISTRICT The Mount Vernon Square Historic District is a late-19th-century commercial and residential neighborhood located within the historic boundaries of the District of Columbia’s Federal City. The historic district covers an area that includes, in whole or in part, twelve city blocks in northwest Washington. The district is bounded generally by New York Avenue on the south; 1st Street on the east; N Street between 1st and 5th Streets and M Street between 5th and 7th Streets on the north; and 7th Street between M Street and New York Avenue on the west. The area includes approximately 420 properties. The 408 contributing buildings were constructed between 1845 and 1945. The neighborhood has a rich collection of architectural styles, includ- ing the Italianate, Queen Anne, and various vernacular expressions of academic styles. The district has a variety of building types and sizes Above: Although platted as part of the Federal City in 1790, the that includes two-story, flat-fronted row houses, three- and four-story, area saw little development in the period between 1790 and 1820. bay-fronted row houses, small apartment buildings, corner stores, and The completion of 7th Street by 1822 laid the foundation for an unusually intact row of 19th-century commercial buildings fronting commercial development and residential growth north of Massachusetts Avenue. 1857 Map of Washington, A. Boschke, on the 1000 block of 7th Street, N.W. and the 600 block of New York Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division. Avenue, N.W. Although exhibiting a diversity of styles and types, the neighborhood’s building stock is united by a common sense of scale, RIght: The laying of streetcar rails along the north/south corridors size, and use of materials and detail.