7350 NBM Blueprnts/REV

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 NCBJ Annual Meeting in Washington, D.C. - Early Ideas Regarding Extracurricular Activities for Attendees and Guests to Consider

2019 NCBJ Annual Meeting in Washington, D.C. - Early Ideas Regarding Extracurricular Activities for Attendees and Guests to Consider There are so many things to do when visiting D.C., many for free, and here are a few you may have not done before. They may make it worthwhile to come to D.C. early or to stay to the end of the weekend. Getting to the Sites: • D.C. Sites and the Pentagon: Metro is a way around town. The hotel is four minutes from the Metro’s Mt. Vernon Square/7th St.-Convention Center Station. Using Metro or walking, or a combination of the two (or a taxi cab) most D.C. sites and the Pentagon are within 30 minutes or less from the hotel.1 Googlemaps can help you find the relevant Metro line to use. Circulator buses, running every 10 minutes, are an inexpensive way to travel to and around popular destinations. Routes include: the Georgetown-Union Station route (with a stop at 9th and New York Avenue, NW, a block from the hotel); and the National Mall route starting at nearby Union Station. • The Mall in particular. Many sites are on or near the Mall, a five-minute cab ride or 17-minute walk from the hotel going straight down 9th Street. See map of Mall. However, the Mall is huge: the Mall museums discussed start at 3d Street and end at 14th Street, and from 3d Street to 14th Street is an 18-minute walk; and the monuments on the Mall are located beyond 14th Street, ending at the Lincoln Memorial at 23d Street. -

OFFICIAL HOTELS Reserve Your Hotel for AUA2020 Annual Meeting May 15 - 18, 2020 | Walter E

AUA2020 Annual Meeting OFFICIAL HOTELS Reserve Your Hotel for AUA2020 Annual Meeting May 15 - 18, 2020 | Walter E. Washington Convention Center | Washington, DC HOTEL NAME RATES HOTEL NAME RATES Marriott Marquis Washington, D.C. 3 Night Min. $355 Kimpton George Hotel* $359 Renaissance Washington DC Dwntwn Hotel 3 Night Min. $343 Kimpton Hotel Monaco Washington DC* $379 Beacon Hotel and Corporate Quarters* $289 Kimpton Hotel Palomar Washington DC* $349 Cambria Suites Washington, D.C. Convention Center $319 Liaison Capitol Hill* $259 Canopy by Hilton Washington DC Embassy Row $369 Mandarin Oriental, Washington DC* $349 Canopy by Hilton Washington D.C. The Wharf* $279 Mason & Rook Hotel * $349 Capital Hilton* $343 Morrison - Clark Historic Hotel $349 Comfort Inn Convention - Resident Designated Hotel* $221 Moxy Washington, DC Downtown $309 Conrad Washington DC 3 Night Min $389 Park Hyatt Washington* $317 Courtyard Washington Downtown Convention Center $335 Phoenix Park Hotel* $324 Donovan Hotel* $349 Pod DC* $259 Eaton Hotel Washington DC* $359 Residence Inn Washington Capitol Hill/Navy Yard* $279 Embassy Suites by Hilton Washington DC Convention $348 Residence Inn Washington Downtown/Convention $345 Fairfield Inn & Suites Washington, DC/Downtown* $319 Residence Inn Downtown Resident Designated* $289 Fairmont Washington, DC* $319 Sofitel Lafayette Square Washington DC* $369 Grand Hyatt Washington 3 Night Min $355 The Darcy Washington DC* $296 Hamilton Hotel $319 The Embassy Row Hotel* $269 Hampton Inn Washington DC Convention 3 Night Min $319 The Fairfax at Embassy Row* $279 Henley Park Hotel 3 Night Min $349 The Madison, a Hilton Hotel* $339 Hilton Garden Inn Washington DC Downtown* $299 The Mayflower Hotel, Autograph Collection* $343 Hilton Garden Inn Washington/Georgetown* $299 The Melrose Hotel, Washington D.C.* $299 Hilton Washington DC National Mall* $315 The Ritz-Carlton Washington DC* $359 Holiday Inn Washington, DC - Capitol* $289 The St. -

NATIONAL BUILDING MUSEUM ANNUAL REPORT 2003 Contents

NATIONAL BUILDING MUSEUM ANNUAL REPORT 2003 Contents 1 Message from the Chair The National Building Museum explores the world and the Executive Director we build for ourselves—from our homes, skyscrapers and public buildings to our parks, bridges and cities. 2 Exhibitions Through exhibitions, education programs and publications, the Museum seeks to educate the 12 Education public about American achievements in architecture, design, engineering, urban planning, and construction. 20 Museum Services The Museum is supported by contributions from 22 Development individuals, corporations, foundations, associations, and public agencies. The federal government oversees and maintains the Museum’s historic building. 24 Contributors 30 Financial Report 34 Volunteers and Staff cover / Looking Skyward in Atrium, Hyatt Regency Atlanta, Georgia, John Portman, 1967. Photograph by Michael Portman. Courtesy John Portman & Associates. From Up, Down, Across. NATIONAL BUILDING MUSEUM ANNUAL REPORT 2003 The 2003 Festival of the Building Arts drew the largest crowd for any single event in Museum history, with nearly 6,000 people coming to enjoy the free demonstrations “The National Building Museum is one of the and hands-on activities. (For more information on the festival, see most strikingly designed spaces in the District. page 16.) Photo by Liz Roll But it has a lot more to offer than nice sightlines. The Museum also offers hundreds of educational programs and lectures for all ages.” —Atlanta Business Chronicle, October 4, 2002 MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR AND THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR responsibility they are taking in creating environmentally-friendly places. Other lecture programs, including a panel discus- sion with I.M. Pei and Leslie Robertson, appealed to diverse audiences. -

Blueprintsvolume XXVII, No

blueprintsVolume XXVII, No. 1–2 NATIONAL BUILDING MUSEUM In Between: The Other Pieces of the Green Puzzle in this issue: HEALTHY Communities, GREEN Communities Word s ,Word s ,Word s Winter & Spring 2008/2009 The Lay of the Landscape Annual Report 2008 in this issue... 2 8 13 18 19 21 23 In Between: The Other Pieces of the Green Puzzle The exhibition Green Community calls attention to important aspects of sustainable design and planning that are sometimes overshadowed by eye-catching works of architecture. The environmental implications of transportation systems, public services, recreational spaces, and other elements of infrastructure must be carefully considered in order to create responsible and livable communities. This issue of Blueprints focuses on the broad environmental imperative from the standpoints of public health, urban and town planning, and landscape architecture. Contents Healthy Communities, ! 2 Green Communities M Cardboard Reinvented Physician Howard Frumkin, of the Centers for Disease Cardboard: one person’s trash is another Control and Prevention, brings his diverse expertise as B an internist, an environmental and occupational health N person’s decorative sculpture, pen and pencil expert, and an epidemiologist to bear on the public health holder, vase, bowl, photo and business card holder, above: Beaverton Round, in suburban Portland, Oregon, was built as part of the metropolitan area’s Transit-Oriented Development Program. implications of community design and planning. p Photo courtesy of the American Planning Association and Portland Metro. stress toy, or whatever you can imagine. Bring out your o Creating Sustainable Landscapes creativity with these durable, versatile, eco-friendly LIQUID h CARDBOARD vases that can be transformed into a myriad from the executive director 8 In an interview, landscape architect Len Hopper discusses s his profession’s inherent commitment to sustainability and of shapes for a variety of uses in your home. -

Draft National Mall Plan / Environmental Impact Statement the National Mall

THE AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT DRAFT NATIONAL MALL PLAN / ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT THE NATIONAL MALL THE MALL CONTENTS: THE AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT THE AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT .................................................................................................... 249 Context for Planning and Development of the National Mall ...................................................................251 1790–1850..................................................................................................................................................251 L’Enfant Plan....................................................................................................................................251 Changes on the National Mall .......................................................................................................252 1850–1900..................................................................................................................................................253 The Downing Plan...........................................................................................................................253 Changes on the National Mall .......................................................................................................253 1900–1950..................................................................................................................................................254 The McMillan Plan..........................................................................................................................254 -

PLSC 177N Politics and Government in Washington DC

SENATE COMMITTEE ON CURRICULAR AFFAIRS COURSE SUBMISSION AND CONSULTATION FORM Principal Faculty Member(s) Proposing Course Name User ID College Department ROBERT SPEEL RWS15 Behrend College (BC) Not Available Academic Home: Behrend College (BC) Type of Proposal: Add Change Drop Current Bulletin Listing Abbreviation: PLSC Number: 177 I am requesting recertification of this course for the new Gen Ed and/or University Requirements Guidelines Course Designation (PLSC 177N) Politics and Government in Washington DC Course Information Cross-Listed Courses: Prerequisites: Corequisites: Concurrents: Recommended Preparations: Abbreviated Title: Pol Gov Wash Dc Discipline: General Education Course Listing: Inter-Domain Special categories for Undergraduate (001-499) courses Foundations Writing/Speaking (GWS) Quantification (GQ) Knowledge Domains Health & Wellness (GHW) Natural Sciences (GN) Arts (GA) Humanities (GH) Social and Behavioral Sciences (GS) Additional Designations Bachelor of Arts International Cultures (IL) United States Cultures (US) Honors Course Common course number - x94, x95, x96, x97, x99 Writing Across the Curriculum First-Year Engagement Program First-Year Seminar Miscellaneous Common Course GE Learning Objectives GenEd Learning Objective: Effective Communication GenEd Learning Objective: Creative Thinking GenEd Learning Objective: Crit & Analytical Think GenEd Learning Objective: Global Learning GenEd Learning Objective: Integrative Thinking GenEd Learning Objective: Key Literacies GenEd Learning Objective: Soc Resp & Ethic Reason Bulletin Listing Minimum Credits: 1 Maximum Credits: 3 Repeatable: NO Department with Humanities And Social Sciences (ERBC_HSS) Curricular Responsibility: Effective Semester: After approval, the Faculty Senate will notify proposers of the effective date for this course change. Please be aware that the course change may not be effective until between 12 to 18 months following approval. -

National Mall & Memorial Parks, 2008 Visitor Study

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior The National Mall and Memorial Parks Washington D.C. the national mall 1997 the legacy plan 1901 mcmillan plan 1791 l'enfant plan 2008 Visitor Study: Destinations, Preferences, and Expenditures August 2009 National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior National Mall and Memorial Parks Washington, D.C. 2008 VISITOR STUDY: DESTINATIONS, PREFERENCES, AND EXPENDITURES Prepared by Margaret Daniels, Ph.D. Laurlyn Harmon, Ph.D. Minkyung Park, Ph.D. Russell Brayley, Ph.D. School of Recreation, Health and Tourism George Mason University 10900 University Blvd., MS 4E5 Manassas VA 20110 August 2009 This page has been left blank intentionally. ii SUMMARY The National Mall is an enduring symbol of the United States (U.S.) that provides an inspiring setting for national memorials and a backdrop for the legislative and executive branches of our government. Enjoyed by millions of visitors each year, the National Mall is a primary location for public gatherings such as demonstrations, national celebrations and special events. Although Washington, D.C., is consistently rated a top destination for domestic and international travelers, and the National Mall is one of the most visited national parks in the country, little systematic attempt has been made to document the influence of the National Mall as a motivating factor for visitation to Washington, D.C., separate from the many other attractions and facilities in the metropolitan area. Accordingly, a visitor study was conducted to assess visitor behaviors and the socioeconomic impacts of visitor spending on the greater Washington, DC metropolitan area. The study addressed the National Mall as a separate entity from the museums and attractions in the area that are not managed by the National Park Service. -

Dc Homeowners' Property Taxes Remain Lowest in The

An Affiliate of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities 820 First Street NE, Suite 460 Washington, DC 20002 (202) 408-1080 Fax (202) 408-8173 www.dcfpi.org February 27, 2009 DC HOMEOWNERS’ PROPERTY TAXES REMAIN LOWEST IN THE REGION By Katie Kerstetter This week, District homeowners will receive their assessments for 2010 and their property tax bills for 2009. The new assessments are expected to decline modestly, after increasing significantly over the past several years. The new assessments won’t impact homeowners’ tax bills until next year, because this year’s bills are based on last year’s assessments. Yet even though 2009’s tax bills are based on a period when average assessments were rising, this analysis shows that property tax bills have decreased or risen only moderately for many homeowners in recent years. DC homeowners continue to enjoy the lowest average property tax bills in the region, largely due to property tax relief policies implemented in recent years. These policies include a Homestead Deduction1 increase from $30,000 to $67,500; a 10 percent cap on annual increases in taxable assessments; and an 11-cent property tax rate cut. The District also adopted a “calculated rate” provision that decreases the tax rate if property tax collections reach a certain target. As a result of these measures, most DC homeowners have seen their tax bills fall — or increase only modestly — over the past four years. In 2008, DC homeowners paid lower property taxes on average than homeowners in surrounding counties. Among homes with an average sales price of $500,000, DC homeowners paid an average tax of $2,725, compared to $3,504 in Montgomery County, $4,752 in PG County, and over $4,400 in Arlington and Fairfax counties. -

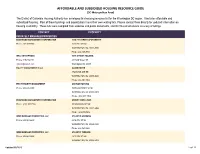

AFFORDABLE and SUBSIDIZED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE (DC Metropolitan Area)

AFFORDABLE AND SUBSIDIZED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE (DC Metropolitan Area) The District of Columbia Housing Authority has developed this housing resource list for the Washington DC region. It includes affordable and subsidized housing. Most of these buildings and organizations have their own waiting lists. Please contact them directly for updated information on housing availability. These lists were compiled from websites and public documents, and DCHA cannot ensure accuracy of listings. CONTACT PROPERTY PRIVATELY MANAGED PROPERTIES EDGEWOOD MANAGEMENT CORPORATION 1330 7TH STREET APARTMENTS Phone: 202-387-7558 1330 7TH ST NW WASHINGTON, DC 20001-3565 Phone: 202-387-7558 WEIL ENTERPRISES 54TH STREET HOUSING Phone: 919-734-1111 431 54th Street, SE [email protected] Washington, DC 20019 EQUITY MANAGEMENT II, LLC ALLEN HOUSE 3760 MINN AVE NE WASHINGTON, DC 20019-2600 Phone: 202-397-1862 FIRST PRIORITY MANAGEMENT ANCHOR HOUSING Phone: 202-635-5900 1609 LAWRENCE ST NE WASHINGTON, DC 20018-3802 Phone: (202) 635-5969 EDGEWOOD MANAGEMENT CORPORATION ASBURY DWELLINGS Phone: (202) 745-7334 1616 MARION ST NW WASHINGTON, DC 20001-3468 Phone: (202)745-7434 WINN MANAGED PROPERTIES, LLC ATLANTIC GARDENS Phone: 202-561-8600 4216 4TH ST SE WASHINGTON, DC 20032-3325 Phone: 202-561-8600 WINN MANAGED PROPERTIES, LLC ATLANTIC TERRACE Phone: 202-561-8600 4319 19th ST S.E. WASHINGTON, DC 20032-3203 Updated 07/2013 1 of 17 AFFORDABLE AND SUBSIDIZED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE (DC Metropolitan Area) CONTACT PROPERTY Phone: 202-561-8600 HORNING BROTHERS AZEEZE BATES (Central -

International Business Guide

WASHINGTON, DC INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS GUIDE Contents 1 Welcome Letter — Mayor Muriel Bowser 2 Welcome Letter — DC Chamber of Commerce President & CEO Vincent Orange 3 Introduction 5 Why Washington, DC? 6 A Powerful Economy Infographic8 Awards and Recognition 9 Washington, DC — Demographics 11 Washington, DC — Economy 12 Federal Government 12 Retail and Federal Contractors 13 Real Estate and Construction 12 Professional and Business Services 13 Higher Education and Healthcare 12 Technology and Innovation 13 Creative Economy 12 Hospitality and Tourism 15 Washington, DC — An Obvious Choice For International Companies 16 The District — Map 19 Washington, DC — Wards 25 Establishing A Business in Washington, DC 25 Business Registration 27 Office Space 27 Permits and Licenses 27 Business and Professional Services 27 Finding Talent 27 Small Business Services 27 Taxes 27 Employment-related Visas 29 Business Resources 31 Business Incentives and Assistance 32 DC Government by the Letter / Acknowledgements D C C H A M B E R O F C O M M E R C E Dear Investor: Washington, DC, is a thriving global marketplace. With one of the most educated workforces in the country, stable economic growth, established research institutions, and a business-friendly government, it is no surprise the District of Columbia has experienced significant growth and transformation over the past decade. I am excited to present you with the second edition of the Washington, DC International Business Guide. This book highlights specific business justifications for expanding into the nation’s capital and guides foreign companies on how to establish a presence in Washington, DC. In these pages, you will find background on our strongest business sectors, economic indicators, and foreign direct investment trends. -

Washington, D.C Site Form

New York Avenue , NE Corridor, Washington, DC Florida Avenue NE & S. Dakota Avenue NE The New York Avenue NE Corridor is located northeast Any framework for this area should consider how to of Downtown. It stretches for approximately 3 miles reduce emissions and promote climate resilience between Florida Avenue NE and South Dakota Avenue while strengthening connectivity, walkability, and NE. It is a major auto-oriented gateway into the city, urban design transitions to adjacent communities and with approximately 100,000 vehicles moving through open space networks, as well as the racial and social the area every day and limited public transit options. equity conditions necessary for long-term social resilience. Robust and sustainable transportation, DC’s Mayor has set ambitious goals for more utility, and civic facility infrastructure, along with affordable housing, and development along the public amenities, are critical to unlocking the corridor could support them. The goal is to deliver as corridor’s full potential. many as 33,000 new housing units, with at least 1/3 of these being affordable. Regeneration should yield a For this site, students can choose to develop a high- vibrant residential and jobs-rich, low-carbon, mixed- level framework or masterplan for the entire site, use corridor. It should be inclusive of new affordable which may include some details on some more specific and market-rate housing units, supported by solutions, such as massing, open space and building sustainable infrastructure and community facilities. type studies. Or, students can choose to design a more detailed response for one or more of these Regeneration will need to preserve some of the subareas, (possibly working in coordinated teams so character and activity of the existing light industrial that all 3 subareas are covered):1: Union Market- (or PDR – Production, Distribution & Repair) uses. -

Insider Tips to Washington, D.C

Insider Tips to Washington, D.C. pril in the nation’s capital can bring snow, rain, sun, and anything in between. The daily A average temperature hovers around the high-60s, but it may range anywhere between 42°F and 70°F, so be sure to pack your suitcase accordingly. Bring your most comfortable shoes. Chances are you’ll be walking to at least one of Washington’s major landmarks: U.S. Capitol Building, Washington Monument, and Lincoln Memorial. The most direct way to get from one to the other is on foot, so make sure your feet feel good, especially since you’ll be walking around no matter how you arrive at your destination. Consider visiting some of the lesser-known locations to avoid huge crowds: FDR Memorial, American Indian Museum, and National Building Museum. Think pink! The conference takes place in the middle of the National Cherry Blossom Festival, which is good and bad. The city will look extra pretty enveloped in millions of pink blossoms. What’s so bad? The crowds! The traffic! The annual Cherry Blossom Parade on the morning of April 14 will close Constitution Avenue from 7th to 17th Streets NW. Riding the Metro When you’re planning a trip via the Metro to the National Mall, you can avoid the crowds at the Smithsonian and L’Enfant Plaza stations. Instead, get off at the Federal Triangle, Capitol South, or Archives stations. They’re just as close to the Mall and you’ll have more time to explore. Each Metro rider must have an individual farecard, which holds between $1.60 and $45.