Biography Pitikwahanapiwiyin, Or Poundmaker, Was, Like

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crowfoot.Pdf

Instructional Outline for Social Studies 9 An Alliance Betrayed A short history of Treaty 7 On September 12, 1877, Chief Crowfoot of the Siksika tribe (Blackfoot) along with chiefs from other tribes signed Treaty 7 along the banks of the Bow River in Southern Alberta. According to the Canadian Encyclopedia, “Aboriginal treaties in Canada are constitutionally recognized agreements between the Crown and Aboriginal people.” Commissioner David Laird, few days before the signing, commented: "In a very few years, the buffalo will probably be all destroyed, and for this reason the queen wishes to help you to live in the future in some other way.” The government depended on Crowfoot’s diplomacy to negotiate with the other chiefs. The government promised that, in exchange for giving up their land, the tribes would have the right to hunt and trap on the “tract surrendered,” the First Nations people would be taught how to grow grain and raise cattle, and they would be given financial assistance and protection. After negotiating the terms of Treaty 7, Chief Crowfoot delivered a speech on behalf of the Blackfoot people: “While I speak, be kind and patient. I have to speak for my people, who are numerous, and who rely upon me to follow that course which in the future will tend to their good. The plains are large and wide. We are the children of the plains, it is our home, and the buffalo has been our food always. I hope you look upon the Blackfeet, Bloods and Sarcees as your children now, and that you will be indulgent and charitable to them. -

The North-West Rebellion 1885 Riel on Trial

182-199 120820 11/1/04 2:57 PM Page 182 Chapter 13 The North-West Rebellion 1885 Riel on Trial It is the summer of 1885. The small courtroom The case against Riel is being heard by in Regina is jammed with reporters and curi- Judge Hugh Richardson and a jury of six ous spectators. Louis Riel is on trial. He is English-speaking men. The tiny courtroom is charged with treason for leading an armed sweltering in the heat of a prairie summer. For rebellion against the Queen and her Canadian days, Riel’s lawyers argue that he is insane government. If he is found guilty, the punish- and cannot tell right from wrong. Then it is ment could be death by hanging. Riel’s turn to speak. The photograph shows What has happened over the past 15 years Riel in the witness box telling his story. What to bring Louis Riel to this moment? This is the will he say in his own defence? Will the jury same Louis Riel who led the Red River decide he is innocent or guilty? All Canada is Resistance in 1869-70. This is the Riel who waiting to hear what the outcome of the trial was called the “Father of Manitoba.” He is will be! back in Canada. Reflecting/Predicting 1. Why do you think Louis Riel is back in Canada after fleeing to the United States following the Red River Resistance in 1870? 2. What do you think could have happened to bring Louis Riel to this trial? 3. -

University of Alberta Perceptions and Parameters of Education As A

University of Alberta Perceptions and Parameters of Education as a Treaty Right within the Context of Treaty 7 Sheila Carr-Stewart A thesis submitted to the Faculîy of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Educational Administration and Leadership Department of Educational Policy Studies Edmonton, Alberta spring 2001 National Library Bibliothèque nationale m*u ofCanada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographk Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. nie Wellington Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Oîîawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantid extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othenirise de celle-ci ne doivent êeimprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation . In memory of John and Betty Carr and Pat and MyrtIe Stewart Abstract On September 22, 1877, representatives of the Blackfoot Confederacy, Tsuu T'ha and Stoney Nations, and Her Majesty's Govemment signed Treaty 7. Over the next century, Canada provided educational services based on the Constitution Act, Section 91(24). -

Rupturing the Myth of the Peaceful Western Canadian Frontier: a Socio-Historical Study of Colonization, Violence, and the North West Mounted Police, 1873-1905

Rupturing the Myth of the Peaceful Western Canadian Frontier: A Socio-Historical Study of Colonization, Violence, and the North West Mounted Police, 1873-1905 by Fadi Saleem Ennab A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Sociology University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2010 by Fadi Saleem Ennab TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................ ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... iii CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW ..................................................................... 8 Mythologizing the Frontier .......................................................................................... 8 Comparative and Critical Studies on Western Canada .......................................... 15 Studies of Colonial Policing and Violence in Other British Colonies .................... 22 Summary of Literature ............................................................................................... 32 Research Questions ..................................................................................................... 33 CHAPTER THREE: THEORETICAL CONSIDERATIONS ......................................... 35 CHAPTER -

The Negotiation and Implementation of Treaty 7, Through 1880

University of Lethbridge Research Repository OPUS http://opus.uleth.ca Theses Arts and Science, Faculty of 2007 The negotiation and implementation of Treaty 7, through 1880 Robert, Sheila Lethbridge, Alta. : University of Lethbridge, Faculty of Arts and Science, 2007 http://hdl.handle.net/10133/619 Downloaded from University of Lethbridge Research Repository, OPUS THE NEGOTIATION AND IMPLEMENTATION OF TREATY 7, THROUGH 1880 Sheila Robert B.A., University of Lethbridge, 2004 A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies Of the University of Lethbridge In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of Native American Studies University of Lethbridge LETHBRIDGE, ALBERTA, CANADA © Sheila Robert, 2007 The objective of this thesis is to examine the archival documents that may be considered by the Supreme Court of Canada if the Treaty 7 Nations were to challenge the Federal Government on the Treaty’s content and meaning. The impetus for this thesis is two-fold. Firstly, recent decisions by the Supreme Court of Canada, in relation to Aboriginal historical treaties, have demonstrated a shift towards legally recognizing the sovereignty of First Nations. As more First Nations challenge the Federal Government on their fulfillment of treaty obligations, Supreme Court decisions will become more elaborate and exhaustive, providing many Nations with an opportunity to address treaty concerns in a more substantive manner than in the past. Secondly, the Blackfoot are my neighbours and I am very honoured to relay -

Continuing to Support the Development of Healthy Self-Sufficient Communities

CONTINUING TO SUPPORT THE DEVELOPMENT OF HEALTHY SELF-SUFFICIENT COMMUNITIES Table of Contents BATC CDC Strategic Plan Page 3—4 Background Page 5 Message from the Chairman Page 6 Members of the Board & Staff Page 7-8 Grant Distribution Summary Page 9-14 Photo Collection Page 15—16 Auditor’s Report Page 17—23 Management Discussion and Analysis Page 24—26 Front Cover Photo Credit: Lance Whitecalf 2 BATC CDC Strategic Plan The BATC Community Development Corporation’s Strategic Planning sessions for 2010—2011 were held commencing September, 2009 with final draft approved on March 15, 2010. CORE VALUES Good governance practice Communication Improve quality of life Respect for culture Sharing VISION Through support of catchment area projects, the BATC CDC will provide grants for the development of healthy self-sufficient communities. Tagline – Continuing to support the development of healthy self-sufficient communities. MISSION BATC CDC distributes a portion of casino proceeds to communities in compliance with the Gaming Framework Agreement and core values. 3 BATC CDC Strategic Plan—continued Goals and Objectives CORE OBJECTIVE GOAL TIMELINE MEASUREMENT VALUE Good Govern- Having good policies Review once yearly May 31/10 Resolution receiving report and ance Practice Effective management team Evaluation Mar 31/11 update as necessary Having effective Board Audit July 31/11 Management regular reporting to Board Accountability/Transparency Auditor’s Management letter Compliant with Gaming Agreement Meet FNMR reporting timelines Communication Create -

Indian Band Revenue Moneys Order Décret Sur Les Revenus Des Bandes D’Indiens

CANADA CONSOLIDATION CODIFICATION Indian Band Revenue Moneys Décret sur les revenus des Order bandes d’Indiens SOR/90-297 DORS/90-297 Current to October 11, 2016 À jour au 11 octobre 2016 Last amended on December 14, 2012 Dernière modification le 14 décembre 2012 Published by the Minister of Justice at the following address: Publié par le ministre de la Justice à l’adresse suivante : http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca http://lois-laws.justice.gc.ca OFFICIAL STATUS CARACTÈRE OFFICIEL OF CONSOLIDATIONS DES CODIFICATIONS Subsections 31(1) and (3) of the Legislation Revision and Les paragraphes 31(1) et (3) de la Loi sur la révision et la Consolidation Act, in force on June 1, 2009, provide as codification des textes législatifs, en vigueur le 1er juin follows: 2009, prévoient ce qui suit : Published consolidation is evidence Codifications comme élément de preuve 31 (1) Every copy of a consolidated statute or consolidated 31 (1) Tout exemplaire d'une loi codifiée ou d'un règlement regulation published by the Minister under this Act in either codifié, publié par le ministre en vertu de la présente loi sur print or electronic form is evidence of that statute or regula- support papier ou sur support électronique, fait foi de cette tion and of its contents and every copy purporting to be pub- loi ou de ce règlement et de son contenu. Tout exemplaire lished by the Minister is deemed to be so published, unless donné comme publié par le ministre est réputé avoir été ainsi the contrary is shown. publié, sauf preuve contraire. -

1 Co-Authoring Relationships: Blackfoot Collections, UK Museums, and Collaborative Practice Alison K. Brown Department of Anthr

Co-authoring Relationships: Blackfoot Collections, UK Museums, and Collaborative Practice Alison K. Brown Department of Anthropology University of Aberdeen Abstract Ceremonial leaders from the four Blackfoot Nations of Siksika, Piikani, Kainai and the Blackfeet work together to pursue the shared goal of accessing museum collections for the collective good of their communities. They also favor an approach which draws on Blackfoot concepts of consensus to allow them to make meaningful relationships with museum workers. This article focuses on the Blackfoot Collections in UK Museums Network, which has aimed to generate and exchange knowledge about little-studied Blackfoot cultural items in British collections. In order to undertake this work, the network established a way of working shaped by Blackfoot concepts of co-existence and practices of relationship-building, as well as by current approaches in museum anthropology which foreground dialogic models yet acknowledge their limitations. Through an ethnographic discussion of the network’s reciprocal meetings, held between 2013 and 2015 in Blackfoot territory in Alberta, Canada, and Montana, US, and in museums in southern England, I examine how Blackfoot practices of co-authoring relationships can shape new relations with museum staff who are critically evaluating the possibilities for collaboration. 1 Introduction This article concerns museum-centered research that is critically informed by emergent museological theories as well as by concepts of consensus and relationship-building practices -

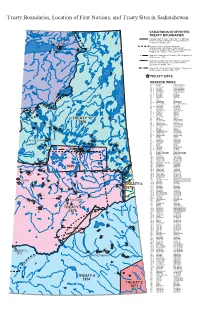

Treaty Boundaries Map for Saskatchewan

Treaty Boundaries, Location of First Nations, and Treaty Sites in Saskatchewan VARIATIONS IN DEPICTED TREATY BOUNDARIES Canada Indian Treaties. Wall map. The National Atlas of Canada, 5th Edition. Energy, Mines and 229 Fond du Lac Resources Canada, 1991. 227 General Location of Indian Reserves, 225 226 Saskatchewan. Wall Map. Prepared for the 233 228 Department of Indian and Northern Affairs by Prairie 231 224 Mapping Ltd., Regina. 1978, updated 1981. 232 Map of the Dominion of Canada, 1908. Department of the Interior, 1908. Map Shewing Mounted Police Stations...during the Year 1888 also Boundaries of Indian Treaties... Dominion of Canada, 1888. Map of Part of the North West Territory. Department of the Interior, 31st December, 1877. 220 TREATY SITES RESERVE INDEX NO. NAME FIRST NATION 20 Cumberland Cumberland House 20 A Pine Bluff Cumberland House 20 B Pine Bluff Cumberland House 20 C Muskeg River Cumberland House 20 D Budd's Point Cumberland House 192G 27 A Carrot River The Pas 28 A Shoal Lake Shoal Lake 29 Red Earth Red Earth 29 A Carrot River Red Earth 64 Cote Cote 65 The Key Key 66 Keeseekoose Keeseekoose 66 A Keeseekoose Keeseekoose 68 Pheasant Rump Pheasant Rump Nakota 69 Ocean Man Ocean Man 69 A-I Ocean Man Ocean Man 70 White Bear White Bear 71 Ochapowace Ochapowace 222 72 Kahkewistahaw Kahkewistahaw 73 Cowessess Cowessess 74 B Little Bone Sakimay 74 Sakimay Sakimay 74 A Shesheep Sakimay 221 193B 74 C Minoahchak Sakimay 200 75 Piapot Piapot TREATY 10 76 Assiniboine Carry the Kettle 78 Standing Buffalo Standing Buffalo 79 Pasqua -

Dmjohnson Draft Thesis Apr 1 2014(3)

“This Is Our Land!” Indigenous Rhetoric and Resistance on the Northern Plains by Daniel Morley Johnson A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Comparative Literature University of Alberta © Daniel Morley Johnson, 2014 Abstract This thesis examines Indigenous rhetorics of resistance from the Treaty Six negotiations in 1876 to the 1930s. Using methods from Comparative Literature and Indigenous literary studies, the thesis situates the rhetoric of northern Plains Indigenous peoples in the context of settler-colonial studies, Indigenous literary nationalism, and Plains Indigenous concepts of nationhood and governance, and introduces the concept of rhetorical autonomy (an extension of literary nationalism) as an organizing framework. The thesis examines the ways Plains Indigenous writers and leaders have resisted settler-colonialism through both rhetorical and physical acts of resistance. Making use of archival and published works, the thesis is a literary and political history of Indigenous peoples from their origins on the northern plains to the period of political organizing after World War I. ii Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge and thank the Indigenous peoples of Treaty Six who have generously allowed me to live and work here in their territory: I hope this thesis honours your histories, is respectful of your stories, and can – in some small way – contribute to your futures. I am grateful to my doctoral committee for their support and guidance: my supervisor, Professor Jonathan Hart, and committee members and examiners, Professors Keavy Martin, Isabel Altamirano-Jiménez, Ellen bielawski, and Odile Cisneros. I am also grateful to Professor Priscilla Settee of the University of Saskatchewan for serving on my committee as external examiner. -

One Battle at a Time

One Battle at a Time By: Brianne Fujimoto-Johnston In 1830 on an unknown date by the Belly River, a hero was born. Chief Crowfoot was born in the Blood (Kainai) tribe but grew up with the Blackfoot (Siksika). His parents gave him the name Astoxkomi (Shot Close) at birth. He was given many names over the years until he received the name Isapo-muxica meaning Crow Big Foot which was later shortened to Crowfoot. Only a few months after Crowfoot was born his father Istowun-eh’pata (Packs a Knife) died in a raid on the Crows. Crowfoot’s mother Axkahp-say-pi (Attacked towards Home) was left alone to raise her 2 children; Crowfoot and his younger brother Mexkim- aotani (Iron Shield). A few years later in 1835, Axkahp-say-pi remarried Akay-nehka-simi (Many Names). Before the age of 20, he went to battle 19 times (but unfortunately was injured 6 times). In 1865, he became the chief of the Big Pipes Band. Later in 1870, he became one of the three head chiefs of that tribe. Being the leader he was he made peace with the Cree. He later adopted a Cree named Poundmaker, who became a leader of his own people. During a Cree raid he rescued missionary Sir Albert Lacombe. Crowfoot also had 3 other children who were girls. He lost most of his kids at young ages to smallpox and tuberculosis. He had numerous wives. On September 12, 1877, Colonel Macleod and Lieutenant-Governor David Laird drew up Treaty 7. Crowfoot took a step forward and persuaded other chiefs to sign the Treaty. -

The Changing Face of the Metis Nation

University of Lethbridge Research Repository OPUS http://opus.uleth.ca Theses Arts and Science, Faculty of 2000 The changing face of the Metis nation Gibbs, Ellen Ann Lethbridge, Alta. : University of Lethbridge, Faculty of Arts and Science, 2000 http://hdl.handle.net/10133/117 Downloaded from University of Lethbridge Research Repository, OPUS THE CHANGING FACE OF THE METIS NATION ELLEN ANN GIBBS THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS IN ENGLISH THE UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY 1998 A Thesis Submitted to the Council on Graduate Studies of the University of Lethbridge in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS LETHBRIDGE, ALBERTA 16 June, 2000 Ellen Ann Gibbs, 2000© DEDICATED TO MY BELOVED SISTER, MARI •iii- ABSTRACT: This paper purposes to answer some questions pertaining to perceptions of Metis identity (individual and collective, subjective and objective) as the Canadian public's conceptualizations of the Metis have been changed during the 80s and 90s by the works of Canadians historians and by popular media. These changes have been stimulated by the politics of Metis participation in: • The Constitution Act, 1982; • The First Ministers' Conferences [FM'Csf, 1983-1987; • The Charlottetown Accord, 1992 Questions asked are (1) who are the modern-day Metis; (2) how do the Metis define themselves, conceptually and legally; (3) how does the Canadian public, in general, define the Metis? The results of the Lethbridge Area Metis Survey (Chapter Three) are valid for the local area but it is possible that they may be generalized. IV- Acknowledgements I obviously owe a debt of gratitude to the many people who helped make this work possible, in particular, to Russel L.