Dmjohnson Draft Thesis Apr 1 2014(3)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

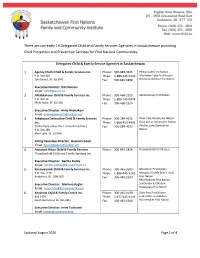

List of FNCFS Agencies in Saskatchewan

There are currently 19 Delegated Child and Family Services Agencies in Saskatchewan providing Child Protection and Prevention Services for First Nations Communities. Delegated Child & Family Service Agencies in Saskatchewan 1 Agency Chiefs Child & Family Services Inc. Phone: 306-883-3345 Pelican Lake First Nation P.O. Box 329 TFree: 1-888-225-2244 Witchekan Lake First Nation Spiritwood, SK S0J 2M0 Fax: 306-883-3838 Whitecap Dakota First Nation Executive Director: Rick Dumais Email: [email protected] 2 Ahtahkakoop Child & Family Services Inc. Phone: 306-468-2520 Ahtahkakoop First Nation P.O. Box 10 TFree: 1-888-745-0478 Mont Nebo, SK S0J 1X0 Fax: 306-468-2524 Executive Director: Anita Ahenakew Email: [email protected] 3 Athabasca Denesuline Child & Family Services Phone: 306-284-4915 Black Lake Denesuline Nation Inc. TFree: 1-888-439-4995 Fond du Lac Denesuline Nation (Yuthe Dene Sekwi Chu L A Koe Betsedi Inc.) Fax: 306-284-4933 Hatchet Lake Denesuline Nation P.O. Box 189 Black Lake, SK S0J 0H0 Acting Executive Director: Rosanna Good Email: Rgood@[email protected] 4 Awasisak Nikan Child & Family Services Phone: 306-845-1426 Thunderchild First Nation Thunderchild Child and Family Services Inc. Executive Director: Bertha Paddy Email: [email protected] 5 Kanaweyimik Child & Family Services Inc. Phone: 306-445-3500 Moosomin First Nation P.O. Box 1270 TFree: 1-888-445-5262 Mosquito Grizzly Bear’s Head Battleford, SK S0M 0E0 Fax: 306-445-2533 First Nation Red Pheasant First Nation Executive Director: Marlene Bugler Saulteaux First Nation Email: [email protected] Sweetgrass First Nation 6 Keyanow Child & Family Centre Inc. -

OTC October Newsletter Final Draft

The Office of the Treaty Commissioner (OTC) is mandated to advance the Treaty goal of establishing good relations among all people of Saskatchewan. The Office of the Treaty Commissioner continues to work with First Nation’s, provincial school systems, and other educational institutions to raise the awareness and understanding of Treaties and First Nations People Quarterly Newsletter Also available on our website at Volume 1 Issue 3 www.otc.ca October 2014 Annual Livelihood – Livelihood – OTC OTC All Nations Woodland Challenges in Saskatchewan First Education Speakers Traditional st Nations Economic Family & Youth Cree Gathering the 21 Century Development Bureau Network Gathering By: George E. Lafond By: Milton Tootoosis By: April Roberts By: Brenda Ahenekew By: Jennifer Heimbecker By: Robin Bendig This year’s theme for There is an urgency Participants also The community of “The people of The “Gathering” the Woodland Cree to defining what learned about Stanley Mission Saskatoon, you focused on Gathering was, “pimâcihisowin” ‘branding’ and hosts a spectacular walked with us when preserving and “Strengthening means as we move communicating their three day event the load was heavy, strengthening First Unity, Celebrating forward in the new communities; called the River and for that we will Nations culture, Culture, Promoting age business planning; Gathering. The always cherish you,” traditions and Community and and financial literacy Gathering is held identity by offering Recognizing next to the oldest various ceremonies History.” Church in and workshops. Saskatchewan 3-4 5 6 7 8 9 DID YOU KNOW? Reconciliation with our sister The OTC welcomes Rhett Sangster as Director of province - OTC commends the Reconciliation and Community Partnerships. -

Key Terms and Concepts for Exploring Nîhiyaw Tâpisinowin the Cree Worldview

Key Terms and Concepts for Exploring Nîhiyaw Tâpisinowin the Cree Worldview by Art Napoleon A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Faculty of Humanities, Department of Linguistics and Faculty of Education, Indigenous Education Art Napoleon, 2014 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Key Terms and Concepts for Exploring Nîhiyaw Tâpisinowin the Cree Worldview by Art Napoleon Supervisory Committee Dr. Leslie Saxon, Department of Linguistics Supervisor Dr. Peter Jacob, Department of Linguistics Departmental Member iii ABstract Supervisory Committee Dr. Leslie Saxon, Department of Linguistics Supervisor Dr. Peter Jacob, Department of Linguistics Departmental MemBer Through a review of literature and a qualitative inquiry of Cree language practitioners and knowledge keepers, this study explores traditional concepts related to Cree worldview specifically through the lens of nîhiyawîwin, the Cree language. Avoiding standard dictionary approaches to translations, it provides inside views and perspectives to provide broader translations of key terms related to Cree values and principles, Cree philosophy, Cree cosmology, Cree spirituality, and Cree ceremonialism. It argues the importance of providing connotative, denotative, implied meanings and etymology of key terms to broaden the understanding of nîhiyaw tâpisinowin and the need -

Imprisonment, Carceral Space, and Settler Colonial Governance in Canada

COLONIAL CARCERALITY AND INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS: IMPRISONMENT, CARCERAL SPACE, AND SETTLER COLONIAL GOVERNANCE IN CANADA By JESSICA E. JURGUTIS B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University © Copyright by Jessica E. Jurgutis, September 2018 i DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (2018) McMaster University (Political Science) Hamilton, ON TITLE: Colonial Carcerality and International Relations: Imprisonment, Carceral Space, and Settler Colonial Governance in Canada AUTHOR: Jessica E. Jurgutis, B.A. (McMaster University), M.A. (York University) SUPERVISOR: Professor J. Marshall Beier NUMBER OF PAGES: vii, 335 ii Abstract This dissertation explores the importance of colonial carcerality to International Relations and Canadian politics. I argue that within Canada, practices of imprisonment and the production of carceral space are a foundational method of settler colonial governance because of the ways they are utilized to reorganize and reconstitute the relationships between bodies and land through coercion, non-consensual inclusion and the use of force. In this project I examine the Treaties and early agreements between Indigenous and European nations, pre-Confederation law and policy, legislative and institutional arrangements and practices during early stages of state formation and capitalist expansion, and contemporary claims of “reconciliation,” alongside the ongoing resistance by Indigenous peoples across Turtle Island. I argue that Canada employs carcerality as a strategy of assimilation, dispossession and genocide through practices of criminalization, punishment and containment of bodies and lands. Through this analysis I demonstrate the foundational role of carcerality to historical and contemporary expressions of Canadian governance within empire, by arguing land as indispensable to understanding the utility of imprisonment and carceral space to extending the settler colonial project. -

The Rose Collection of Moccasins in the Canadian Museum of Civilization : Transitional Woodland/Grassl and Footwear

THE ROSE COLLECTION OF MOCCASINS IN THE CANADIAN MUSEUM OF CIVILIZATION : TRANSITIONAL WOODLAND/GRASSL AND FOOTWEAR David Sager 3636 Denburn Place Mississauga, Ontario Canada, L4X 2R2 Abstract/Resume Many specialists assign the attribution of "Plains Cree" or "Plains Ojibway" to material culture from parts of Manitoba and Saskatchewan. In fact, only a small part of this area was Grasslands. Several bands of Cree and Ojibway (Saulteaux) became permanent residents of the Grasslands bor- ders when Reserves were established in the 19th century. They rapidly absorbed aspects of Plains material culture, a process started earlier farther west. This paper examines one such case as revealed by footwear. Beaucoup de spécialistes attribuent aux Plains Cree ou aux Plains Ojibway des objets matériels de culture des régions du Manitoba ou de la Saskatch- ewan. En fait, il n'y a qu'une petite partie de cette région ait été prairie. Plusieurs bandes de Cree et d'Ojibway (Saulteaux) sont devenus habitants permanents des limites de la prairie quand les réserves ont été établies au XIXe siècle. Ils ont rapidement absorbé des aspects de la culture matérielle des prairies, un processus qu'on a commencé plus tôt plus loin à l'ouest. Cet article examine un tel cas comme il est révélé par des chaussures. The Canadian Journal of Native Studies XIV, 2(1 994):273-304. 274 David Sager The Rose Moccasin Collection: Problems in Attribution This paper focuses on a unique group of eight pair of moccasins from southern Saskatchewan made in the mid 1880s. They were collected by Robert Jeans Rose between 1883 and 1887. -

BATC CDC Annual Report 2010-2011

ANNUAL REPORT 2010-2011 SUPPORTING THE DEVELOPMENT OF HEALTHY COMMUNITIES Table of Contents BATC CDC Strategic Plan Page 4—5 Background Page 6 Message from the Chairman Page 7 Members of the Board & Staff Page 8 Grant Distribution Summary Page 9—11 Auditor’s Report and Financial Statements March 31, 2011 Page 12—19 Photo Collection Page 20—21 Management Discussion and Analysis Page 22—23 Front Cover Photo Credit: Sharon Angus 3 BATC CDC Strategic Plan The BATC Community Development Corporation’s Strategic Planning sessions for 2011-2012 began on December 8, 2010 with the final draft approved on March 15, 2011. CORE VALUES Good governance practice Communication Improve quality of life Respect for culture Sharing Legacy VISION Through support of catchment area projects, the BATC CDC will provide grants supporting the development of healthy communities. Tagline – Supporting the development of healthy communities MISSION BATC CDC distributes a portion of casino proceeds to communities in compliance with the Gaming Framework Agreement and core values. 4 BATC CDC Strategic Plan—continued Goals and Objectives Core Value Objective Goal Timeline Measurement Good Having good policies Review once yearly May 31, 2012 Resolution receiving report and Governance update as necessary Practice Effective management Evaluation Mar 31, 2012 Management regular reporting to team Board Having effective Board Audit July 31, 2012 Auditor’s Management letter Accountability/ Audit July 31, 2012 Auditor’s Financial Statements Transparency Compliant with Gaming Aug -

Thistle Indian-Trader.Pdf

THE UNIVERS]TY OF MANITOBA INDIAN--TRADER RELATIONS: AN ETHNOH]STORY OF WESTERN WOODS CREE.-HUDSONIS BAY COMPANY TRADER CONTACT IN THE CUMBERLAND HOUSE--THE PAS REGION TO 1840 A thesis subnitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirenents for the degree of Master of Art s in the Indívidual Tnterdisciplinary Programne (Anthropology, History, Educat i on) by Paul Clifford Thistle .Tu 1v 19 8 3 INDIAN--TRADDR REI-ATIONS: AN ETHNOII ISTORY 0F I¡]ESTERN WOODS CREE--HUDSONTS BAY COMPANY TRADER CONTACT IN THE CUMBERLAND HOUSE--THE PAS REGION TO I84O by PauI Cl ifford Thistle A tlìesis submitted to the Faculty of G¡aduate Studies ol the University of Manitobâ in partial fulfillment of the requirenìer.ìts of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS @ 1983 Pe¡missjon has been granted to the LIBRARY OF THE UNIVER- SITY OF MANITOBA to lend or sell copies of this thesis. to the NATIONAL LIBRARY OF CANADA to microfilnr this thesis and to lend or sell copies of the film, and UNIVERSITy MICROFILMS to publish an abstract of this thesis. The author reserves other publication rights, and neither the thesis nor extensive extracts from it may be printed or other- wise reproduced without the autho¡'s w¡ittelr perurissiotr. TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ABSTRACT vl1 CHAPTER I ]NTRODUCT ION 1 The Prob 1em 1 Purpose 3 Scope 4 S igni ficance 5 Method 11 The o ry T4 (i) Ethnic/Race Relations Theory 16 (ii) Ethnicity Theory 19 (iii) Culture Change and Acculturat i on Theory 22 Sumrnary Discussion 26 II ETHNOGRAPHY OF THE RELATION z8 Introduction . -

2015-2016 Annual Report & Audited

Photo Courtesy of MLT Photography The flag of the Ahtahkakoop Cree Nation was officially commissioned on September 15, 1995 and was designed by Willard Ahenakew, great, great grandson of Chief Ahtahkakoop. The flag design references the Cree name “Ahtahkakoop” which translated into English means Starblanket. There are 276 stars representing the number of ancestors of the first Treaty 6 pay list of 1876, with 133 larger stars representing the men and women, and 143 stars representing the children. The Sun, Thunderbird, Medicine Staff and Buffalo represents important emblems of the Plains Cree culture. The night our namesake was born, it is said that the sky was unusually bright with many, many stars and thus he was given the name “Ahtahkakoop”. Our vision is to be a leader in Governance, Administration and Economic Development using the guiding principle of Chief Ahtahkakoop; “Let Us not think of Ourselves, but of Our Children’s Children”. Welcome to the Ahtahkakoop 2015-2016 Annual Report and Audited Financial Statements. It is with great pride that we once again able to provide this report to you with all this important information and it is with great honor to say that we are in our 9th consecutive year of having an Unqualified Audit for the First Nation. As with previous years, the purpose of this publication is to inform our Band Membership of each department’s business focus, previous year’s results and new objectives for the coming years. Over the past year, we have shifted our focus to the Health and Safety of our Community. As part of community safety, we have lobbied the Federal Government for funding for a New Fire Hall and Fire Truck. -

The North-West Rebellion 1885 Riel on Trial

182-199 120820 11/1/04 2:57 PM Page 182 Chapter 13 The North-West Rebellion 1885 Riel on Trial It is the summer of 1885. The small courtroom The case against Riel is being heard by in Regina is jammed with reporters and curi- Judge Hugh Richardson and a jury of six ous spectators. Louis Riel is on trial. He is English-speaking men. The tiny courtroom is charged with treason for leading an armed sweltering in the heat of a prairie summer. For rebellion against the Queen and her Canadian days, Riel’s lawyers argue that he is insane government. If he is found guilty, the punish- and cannot tell right from wrong. Then it is ment could be death by hanging. Riel’s turn to speak. The photograph shows What has happened over the past 15 years Riel in the witness box telling his story. What to bring Louis Riel to this moment? This is the will he say in his own defence? Will the jury same Louis Riel who led the Red River decide he is innocent or guilty? All Canada is Resistance in 1869-70. This is the Riel who waiting to hear what the outcome of the trial was called the “Father of Manitoba.” He is will be! back in Canada. Reflecting/Predicting 1. Why do you think Louis Riel is back in Canada after fleeing to the United States following the Red River Resistance in 1870? 2. What do you think could have happened to bring Louis Riel to this trial? 3. -

Government Spending and Own-Source Revenue for Canada’S Aboriginals : a Comparative Analysis

MARCH 2016 Government Spending and Own-Source Revenue for Canada’s Aboriginals : A Comparative Analysis. By Ravina Bains and Kayla Ishkanian March 2016 Government Spending and Own-Source Revenue for Canada’s Aboriginals: A Comparative Analysis by Ravina Bains and Kayla Ishkanian fraserinstitute.org Contents Executive summary / iii Introduction / 1 Spending on Canada’s Aboriginals / 2 Own-source revenue / 12 Conclusion / 18 References / 19 About the authors / 23 Acknowledgments / 23 Publishing information / 23 Supporting the Fraser Institute / 24 Purpose, funding, & independence / 24 About the Fraser Institute / 25 Editorial Advisory Board / 26 fraserinstitute.org / i fraserinstitute.org Executive summary With average unemployment rates on reserve above 20 percent and graduation rates below 40 percent, there is a clear gap in outcomes between Aboriginals and non-Aboriginals in Canada. This is sometimes blamed on funding dispar- ities. This study provides a fact-based evaluation of the oft-heard claims that spending on Canada’s aboriginal population is not comparable to spending on other Canadians. It examines actual spending on aboriginal Canadians using data from the federal department of Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada, Health Canada, and provincial governments, sources where aborig- inal spending was clearly identified in the public accounts. Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) The data used to compare INAC spending on aboriginal matters with total federal program spending runs from 1946/47 through 2013/14. Per-person comparisons date from 1949/50. The increase in spending on Canada’s aboriginal peoples has been sig- nificant. In real terms, total department spending on Canada’s aboriginal peoples rose from $82 million annually in 1946/47 to over $7.9 billion in 2013/14 (all figures in this report are inflation-adjusted to 2015 dollars). -

2016-2017 Annual Report NALMA

2016-2017 Annual Report NALMA National Aboriginal Lands Managers Association 1024 Mississauga Street Curve Lake, Ontario K0L 1R0 Partners and Affiliations Acronyms ACLS Association of Canada Land Surveyors ARALA Atlantic Region Aboriginal Lands Association ATR Additions to Reserve BCALM British Columbia Aboriginal Land Managers Cando Council for the Advancement of Native Development Officers COEMRP Centre of Excellence for Matrimonial Real Property FHRMIRA Family Homes on Reserves and Matrimonial Interests or Rights Act FNLMA First Nation Land Management Act FNLMAQ&L First Nation Lands Managers Association for Quebec and Labrador GIS Geographic Information Systems ILRS Indian Lands Registry System INAC Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada KA Kanawayihetaytan Askiy LEDAC Lands and Economic Development Advisory Committee NALMA National Aboriginal Lands Managers Association NRCan Natural Resources Canada OALA Ontario Aboriginal Lands Association PLA Planning and Land Administrators PLAN Planning and Land Administrators of Nunavut PLMCP Professional Lands Management Certification Program RLA Regional Lands Associations RLEMP Reserve Land and Environment Management Program SALT Saskatchewan Aboriginal Lands Technicians SG Self Government TALSAA Treaty and Aboriginal Land Stewards Association of Alberta Uske Manitoba Uske 2 NALMA 2016-2017 Annual Report TABLE OF CONTENTS Joint Letter from the NALMA Board and Executive Director 4 Regional Lands Association and NALMA Membership 5 NALMA Mandate, Mission, & Values 6 Regional Lands Associations -

KI LAW of INDIGENOUS PEOPLES KI Law Of

KI LAW OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES KI Law of indigenous peoples Class here works on the law of indigenous peoples in general For law of indigenous peoples in the Arctic and sub-Arctic, see KIA20.2-KIA8900.2 For law of ancient peoples or societies, see KL701-KL2215 For law of indigenous peoples of India (Indic peoples), see KNS350-KNS439 For law of indigenous peoples of Africa, see KQ2010-KQ9000 For law of Aboriginal Australians, see KU350-KU399 For law of indigenous peoples of New Zealand, see KUQ350- KUQ369 For law of indigenous peoples in the Americas, see KIA-KIX Bibliography 1 General bibliography 2.A-Z Guides to law collections. Indigenous law gateways (Portals). Web directories. By name, A-Z 2.I53 Indigenous Law Portal. Law Library of Congress 2.N38 NativeWeb: Indigenous Peoples' Law and Legal Issues 3 Encyclopedias. Law dictionaries For encyclopedias and law dictionaries relating to a particular indigenous group, see the group Official gazettes and other media for official information For departmental/administrative gazettes, see the issuing department or administrative unit of the appropriate jurisdiction 6.A-Z Inter-governmental congresses and conferences. By name, A- Z Including intergovernmental congresses and conferences between indigenous governments or those between indigenous governments and federal, provincial, or state governments 8 International intergovernmental organizations (IGOs) 10-12 Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) Inter-regional indigenous organizations Class here organizations identifying, defining, and representing the legal rights and interests of indigenous peoples 15 General. Collective Individual. By name 18 International Indian Treaty Council 20.A-Z Inter-regional councils. By name, A-Z Indigenous laws and treaties 24 Collections.