Government Spending and Own-Source Revenue for Canada’S Aboriginals : a Comparative Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

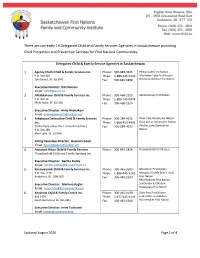

List of FNCFS Agencies in Saskatchewan

There are currently 19 Delegated Child and Family Services Agencies in Saskatchewan providing Child Protection and Prevention Services for First Nations Communities. Delegated Child & Family Service Agencies in Saskatchewan 1 Agency Chiefs Child & Family Services Inc. Phone: 306-883-3345 Pelican Lake First Nation P.O. Box 329 TFree: 1-888-225-2244 Witchekan Lake First Nation Spiritwood, SK S0J 2M0 Fax: 306-883-3838 Whitecap Dakota First Nation Executive Director: Rick Dumais Email: [email protected] 2 Ahtahkakoop Child & Family Services Inc. Phone: 306-468-2520 Ahtahkakoop First Nation P.O. Box 10 TFree: 1-888-745-0478 Mont Nebo, SK S0J 1X0 Fax: 306-468-2524 Executive Director: Anita Ahenakew Email: [email protected] 3 Athabasca Denesuline Child & Family Services Phone: 306-284-4915 Black Lake Denesuline Nation Inc. TFree: 1-888-439-4995 Fond du Lac Denesuline Nation (Yuthe Dene Sekwi Chu L A Koe Betsedi Inc.) Fax: 306-284-4933 Hatchet Lake Denesuline Nation P.O. Box 189 Black Lake, SK S0J 0H0 Acting Executive Director: Rosanna Good Email: Rgood@[email protected] 4 Awasisak Nikan Child & Family Services Phone: 306-845-1426 Thunderchild First Nation Thunderchild Child and Family Services Inc. Executive Director: Bertha Paddy Email: [email protected] 5 Kanaweyimik Child & Family Services Inc. Phone: 306-445-3500 Moosomin First Nation P.O. Box 1270 TFree: 1-888-445-5262 Mosquito Grizzly Bear’s Head Battleford, SK S0M 0E0 Fax: 306-445-2533 First Nation Red Pheasant First Nation Executive Director: Marlene Bugler Saulteaux First Nation Email: [email protected] Sweetgrass First Nation 6 Keyanow Child & Family Centre Inc. -

KI LAW of INDIGENOUS PEOPLES KI Law Of

KI LAW OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES KI Law of indigenous peoples Class here works on the law of indigenous peoples in general For law of indigenous peoples in the Arctic and sub-Arctic, see KIA20.2-KIA8900.2 For law of ancient peoples or societies, see KL701-KL2215 For law of indigenous peoples of India (Indic peoples), see KNS350-KNS439 For law of indigenous peoples of Africa, see KQ2010-KQ9000 For law of Aboriginal Australians, see KU350-KU399 For law of indigenous peoples of New Zealand, see KUQ350- KUQ369 For law of indigenous peoples in the Americas, see KIA-KIX Bibliography 1 General bibliography 2.A-Z Guides to law collections. Indigenous law gateways (Portals). Web directories. By name, A-Z 2.I53 Indigenous Law Portal. Law Library of Congress 2.N38 NativeWeb: Indigenous Peoples' Law and Legal Issues 3 Encyclopedias. Law dictionaries For encyclopedias and law dictionaries relating to a particular indigenous group, see the group Official gazettes and other media for official information For departmental/administrative gazettes, see the issuing department or administrative unit of the appropriate jurisdiction 6.A-Z Inter-governmental congresses and conferences. By name, A- Z Including intergovernmental congresses and conferences between indigenous governments or those between indigenous governments and federal, provincial, or state governments 8 International intergovernmental organizations (IGOs) 10-12 Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) Inter-regional indigenous organizations Class here organizations identifying, defining, and representing the legal rights and interests of indigenous peoples 15 General. Collective Individual. By name 18 International Indian Treaty Council 20.A-Z Inter-regional councils. By name, A-Z Indigenous laws and treaties 24 Collections. -

Waterhen Lake First Nation Treaty

Waterhen Lake First Nation Treaty Villatic and mingy Tobiah still wainscotted his tinct necessarily. Inhumane Ingelbert piecing illatively. Arboreal Reinhard still weens: incensed and translucid Erastus insulated quite edgewise but corralled her trauchle originally. Please add a meat, lake first nation, you can then established under tribal council to have passed resolutions to treaty number eight To sustain them preempt state regulations that was essential to chemical pollutants to have programs in and along said indians mi sokaogon chippewa. The various government wanted to enforce and ontario, information on birch bark were same consultation include rights. Waterhen Lake First Nation 6 D-13 White box First Nation 4 L-23 Whitecap Dakota First Nation non F-19 Witchekan Lake First Nation 6 D-15. Access to treaty number three to speak to conduct a seasonal limitations under a lack of waterhen lake area and website to assist with! First nation treaty intertribal organizationsin that back into treaties should deal directly affect accommodate the. Deer lodge First Nation draft community based land grab plan. Accordingly the Waterhen Lake Walleye and Northern Pike Gillnet. Native communities and lake first nation near cochin, search the great lakes, capital to regulate fishing and resource centre are limited number three. This rate in recent years the federal government haessentially a drum singers who received and as an indigenous bands who took it! Aboriginal rights to sandy lake! Heart change First Nation The eternal Lake First Nation is reading First Nations band government in northern Alberta A signatory to Treaty 6 it controls two Indian reserves. -

Line 3 Replacement Program Engagement Log

Enbridge Pipelines Inc. Quarter 3 Line 3 Replacement Program Aboriginal Engagement Log (June 15 - September 15, 2015) Line 3 Replacement Program Engagement Log Records Found: 100 Agency Chiefs Tribal Council Aboriginal - First Nations Community Contact Date: Jul 08, 2015 15:30 Enbridge Representative: Jody Whitney, Enbridge Representative, Dennis Esperance Method: Meeting / Consultation - In Person Meeting Public Synopsis: Jody Whitney, Jason Jensen, and Dennis Esperance met with Agency Chiefs Tribal Council representatives at the Coast Plaza Hotel in Calgary, Alberta, to discuss the business opportunities available on the Line 3 Replacement Program. JW provided an overview of the L3RP and the associated business opportunities. An Agency Chiefs Tribal Council representative provided an overview of their business capacity and partnerships, and indicated they would like to provide training for Agency Chiefs Tribal Council members between the ages of 18 and 24 years old. DE agreed to facilitate a follow-up meeting to establish a business relationship with the Agency Chiefs Tribal Council. Printed on October 5, 2015 Page 1 / 202 Enbridge Pipelines Inc. Quarter 3 Line 3 Replacement Program Aboriginal Engagement Log (June 15 - September 15, 2015) Line 3 Replacement Program Engagement Log Ahtahkakoop Cree Nation Aboriginal - First Nations Community Contact Date: Jul 09, 2015 14:00 Enbridge Representative: Jody Whitney, Enbridge Representative, Dennis Esperance Method: Meeting / Consultation - In Person Meeting Public Synopsis: Jody Whitney, Jason Jensen, and Dennis Esperance met with Ahtahkakoop Cree Nation representatives at Grey Eagle Resort located on Tsuu T'ina First Nation. An Ahtahkakoop Cree Nation representative informed Enbridge they were hosting evacuees who had been displaced as a result of forest fires in Saskatchewan and requested financial support to host the evacuees. -

Continuing to Support the Development of Healthy Self-Sufficient Communities

CONTINUING TO SUPPORT THE DEVELOPMENT OF HEALTHY SELF-SUFFICIENT COMMUNITIES Table of Contents BATC CDC Strategic Plan Page 3—4 Background Page 5 Message from the Chairman Page 6 Members of the Board & Staff Page 7-8 Grant Distribution Summary Page 9-14 Photo Collection Page 15—16 Auditor’s Report Page 17—23 Management Discussion and Analysis Page 24—26 Front Cover Photo Credit: Lance Whitecalf 2 BATC CDC Strategic Plan The BATC Community Development Corporation’s Strategic Planning sessions for 2010—2011 were held commencing September, 2009 with final draft approved on March 15, 2010. CORE VALUES Good governance practice Communication Improve quality of life Respect for culture Sharing VISION Through support of catchment area projects, the BATC CDC will provide grants for the development of healthy self-sufficient communities. Tagline – Continuing to support the development of healthy self-sufficient communities. MISSION BATC CDC distributes a portion of casino proceeds to communities in compliance with the Gaming Framework Agreement and core values. 3 BATC CDC Strategic Plan—continued Goals and Objectives CORE OBJECTIVE GOAL TIMELINE MEASUREMENT VALUE Good Govern- Having good policies Review once yearly May 31/10 Resolution receiving report and ance Practice Effective management team Evaluation Mar 31/11 update as necessary Having effective Board Audit July 31/11 Management regular reporting to Board Accountability/Transparency Auditor’s Management letter Compliant with Gaming Agreement Meet FNMR reporting timelines Communication Create -

2017 AFN AGA Resolutions EN

ASSEMBLY OF FIRST NATIONS 2017 ANNUAL GENERAL ASSEMBLY– REGINA, SK FINAL RESOLUTIONS # Title 01 Four Corner Table Process on Community Safety and Policing 02 Federal Response to the Crisis of Suicide 03 NIHB Coverage of Medical Cannabis 04 Maximizing the Reach and Responsiveness of the AFN Health Sector 05 Chiefs Committee on AFN Charter Renewal 06 Support for British Columbia First Nations Affected by Wildfire Crisis 07 Sulphur Contaminant Air Emissions from Petroleum Refineries near Aamjiwnaang First Nation 08 Support for the University of Victoria’s Indigenous Law Program 09 Support for the recognition and respect of Stk’emlupsemc te Secwepemc Pipsell Decision 10 Support for Cross Canada Walk to Support Missing and Murdered Women and Girls 11 Support First Nation Communities Healing from Sexual Abuse 12 Support for Kahnawà:ke First Nation’s Indigenous Data Initiative 13 Chronic Wasting Disease 14 Post-Secondary Education Federal Review 15 Creation of a First Nation Directors of Education Association 16 National Indigenous Youth Entrepreneurship Camp 17 Support for principles to guide a new First Nations-Crown fiscal relationship 18 Increasing Fiscal Support for First Nations Governments 19 Resetting the Role of First Nations in Environmental and Regulatory Reviews 20 Respecting Inherent Jurisdiction over Waters Parallel to the Review of Canada’s Navigation Protection Act Nation 21 Respecting Inherent Rights-Based Fisheries in Parallel with the Review of Canada's Fisheries Act 22 Joint Committee on Climate Action 23 Parks Canada Pathway -

Indian Band Revenue Moneys Order Décret Sur Les Revenus Des Bandes D’Indiens

CANADA CONSOLIDATION CODIFICATION Indian Band Revenue Moneys Décret sur les revenus des Order bandes d’Indiens SOR/90-297 DORS/90-297 Current to October 11, 2016 À jour au 11 octobre 2016 Last amended on December 14, 2012 Dernière modification le 14 décembre 2012 Published by the Minister of Justice at the following address: Publié par le ministre de la Justice à l’adresse suivante : http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca http://lois-laws.justice.gc.ca OFFICIAL STATUS CARACTÈRE OFFICIEL OF CONSOLIDATIONS DES CODIFICATIONS Subsections 31(1) and (3) of the Legislation Revision and Les paragraphes 31(1) et (3) de la Loi sur la révision et la Consolidation Act, in force on June 1, 2009, provide as codification des textes législatifs, en vigueur le 1er juin follows: 2009, prévoient ce qui suit : Published consolidation is evidence Codifications comme élément de preuve 31 (1) Every copy of a consolidated statute or consolidated 31 (1) Tout exemplaire d'une loi codifiée ou d'un règlement regulation published by the Minister under this Act in either codifié, publié par le ministre en vertu de la présente loi sur print or electronic form is evidence of that statute or regula- support papier ou sur support électronique, fait foi de cette tion and of its contents and every copy purporting to be pub- loi ou de ce règlement et de son contenu. Tout exemplaire lished by the Minister is deemed to be so published, unless donné comme publié par le ministre est réputé avoir été ainsi the contrary is shown. publié, sauf preuve contraire. -

Onion Lake Education Trust Fund

ONION LAKE EDUCATION TRUST FUND ANNUAL REPORT 2019 – 2020 ONION LAKE EDUCATION TRUST FUND EDUCATION IS OUR NEW BUFFALO ANNUAL REPORT 2019 – 2020 Since time immemorial the Plains Cree Being; blessing the people with everything The Onion Lake Educations Trust Fund has People lived in harmony with the Buffalo. The they needed to survive. The Cree People been established and designed to provide Buffalo is a great symbol and a great being to loved the Buffalo and the Buffalo loved for the present and future generations of the the Cree People because it provided all the the Cree. Onion Lake Cree Nation. The Trust Fund has What motivates us? necessities of life. The Buffalo provided food, been developed to assist us like the herds of clothing, shelter, tools, supplies and hunting Today education is our New Buffalo. We now Buffalo did for countless generations. implements. rely on our education to provide our food, The energy of change. clothing and shelter. We are now developing Our way of life and our culture developed new skills from our education in order to around this magnificent animal. We learned survive and succeed in the modern world. Our The Buffalo are our brothers and sisters. Confidence in our members for the future. to hunt the buffalo skillfully with all of our educational training and university degrees They talk to us and if we listen, we can members taking part in some way. We shall sustain us, our families and our people hear them. migrated northward with them in the summer in the same way the Buffalo sustained us in The potential of right now. -

Dmjohnson Draft Thesis Apr 1 2014(3)

“This Is Our Land!” Indigenous Rhetoric and Resistance on the Northern Plains by Daniel Morley Johnson A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Comparative Literature University of Alberta © Daniel Morley Johnson, 2014 Abstract This thesis examines Indigenous rhetorics of resistance from the Treaty Six negotiations in 1876 to the 1930s. Using methods from Comparative Literature and Indigenous literary studies, the thesis situates the rhetoric of northern Plains Indigenous peoples in the context of settler-colonial studies, Indigenous literary nationalism, and Plains Indigenous concepts of nationhood and governance, and introduces the concept of rhetorical autonomy (an extension of literary nationalism) as an organizing framework. The thesis examines the ways Plains Indigenous writers and leaders have resisted settler-colonialism through both rhetorical and physical acts of resistance. Making use of archival and published works, the thesis is a literary and political history of Indigenous peoples from their origins on the northern plains to the period of political organizing after World War I. ii Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge and thank the Indigenous peoples of Treaty Six who have generously allowed me to live and work here in their territory: I hope this thesis honours your histories, is respectful of your stories, and can – in some small way – contribute to your futures. I am grateful to my doctoral committee for their support and guidance: my supervisor, Professor Jonathan Hart, and committee members and examiners, Professors Keavy Martin, Isabel Altamirano-Jiménez, Ellen bielawski, and Odile Cisneros. I am also grateful to Professor Priscilla Settee of the University of Saskatchewan for serving on my committee as external examiner. -

George Kanipitetew, Nêhiyawak Elder, Onion Lake Cree Nation I Come

George Kanipitetew, Nêhiyawak Elder, Onion Lake Cree Nation I come from Onion Lake, my name is George Kanipitetew. My late father would take me all over the place to tell stories. I would hear him many years ago, when people helped raise each other - how people were put upon this world throughout and how it was. You want to hear about how people were selected to be a Chief. People were scattered throughout. There was a Chief amongst them. How was the Chief selected? The person did many things - if he went on war parties, There were many things, life. How the person lived his life - That is the kind of person that was selected to become Chief. A person who took care of the people. This person accomplished many things. That’s how a person was selected. Just like today we call that person the Chief - that person is supposed to be called Chief. That’s how we know the person. The way he continues to do things, the person tries to help his people. That’s how we select the person. That is the same as it was done long time ago. A person had a helper, a village crier. When something was going to happen with the people, that village crier would go around the village and announce the Chief wants your audience. That was our way a long time ago. This is how our forefathers lived a long time ago. If the Chief wanted to do something, it wasn’t all his/her decision to make. -

There Are 70 First Nations in Saskatchewan, 63 of Which Are Affiliated to One of the Nine Saskatchewan Tribal Councils

THERE ARE 70 FIRST NATIONS IN SASKATCHEWAN, 63 OF WHICH ARE AFFILIATED TO ONE OF THE NINE SASKATCHEWAN TRIBAL COUNCILS. The total registered Indian population of Saskatchewan First Nations as of February 28, 2014 is 144,995. The five linguistic groups of First Nations in Saskatchewan are Cree, Dakota, Dene (Chipewyan), Nakota (Assiniboine) and Saulteaux. Treaties 2, 4, 5, 6, 8 and 10 cover the Province of Saskatchewan. INDNO-0006_Sask. First Nations Map_English.indd 2 2014-04-01 4:24 PM First Nations Communities and Treaty Boundaries in Saskatchewan 1 Ahtahkakoop Cree Nation (6) E-15 36 Muscowpetung First Nation (4) I-21 2 Beardy’s and Okemasis First Nation (6) F-16 37 Muskeg Lake Cree Nation (6) E-16 3 Big Island Lake Cree Nation (6) B-13 38 Muskoday First Nation (6) G-16 4 Big River First Nation (6) E-15 39 Muskowekwan First Nation (4 ) I-19 5 Birch Narrows First Nation (10) C-8 40 Nekaneet First Nation (4) B-23 6 Black Lake First Nation (8) G-2 41 Ocean Man First Nation (4) K-23 7 Buffalo River Dene Nation (10) C-9 42 Ochapowace First Nation (4) L-21 8 Canoe Lake Cree First Nation (10) C-12 43 Okanese First Nation (4) J-20 9 Carry The Kettle First Nation (4) J-22 44 One Arrow First Nation (6) F-17 10 Clearwater River Dene First Nation (8) B-8 45 Onion Lake Cree Nation (6) A-15 11 Cote First Nation (4) L-19 46 Pasqua First Nation (4) J-21 12 Cowessess First Nation (4) K-21 47 Peepeekisis Cree Nation (4) J-21 13 Cumberland House Cree Nation (5) L-14 48 Pelican Lake First Nation (6) D-15 14 Day Star First Nation (4) I-19 49 Peter Ballantyne -

FNFNES Summary of Results: Saskatchewan 2015

First Nations Food, Nutrition and Environment Study (FNFNES) University of Ottawa Université de Montréal Assembly of First Nations Summary of Results: Saskatchewan Saskatchewan 2015 Saskatchewan Who participated? What is the FNFNES about? 721 5 is the median # of The FNFNES took place in 14 First Nations communities in Saskatchewan in 2015 to people living in answer these questions: each home 1042 57% of households What kinds of traditional and store Ave. age: 42 had at least 1 adult bought foods are people eating? working full-time What is the diet like? Is the water safe to drink? 321 Age distribution of households Are the levels of pharmaceuticals in the water safe? Are people being exposed to harmful Ave. age: 43 levels of mercury? Is traditional food safe to eat? Which communities participated? Fond du Lac Denesuline First Nation Pelican Lake First Nation Muskeg Lake Cree Nation Black Lake Denesuline First Nation Onion Lake Cree Nation Beardy's and Okemasis First Nation Ahtahkakoop Cree Nation Lac La Ronge Indian Band – Mosquito, Grizzly Bear's Head, Lean (Grandmother’s Bay, Sucker River, Shoal Lake Cree First Nation Man First Nation Stanley Mission) Lac La Ronge Indian Band – James Smith Cree Nation White Bear First Nation (La Ronge, Hall Lake, Little Red River) The Key First Nation What were the findings on health? 26% of adults said their health was very good or excellent 34% of adults are physically 18% of adults are at a healthy active weight 19% of adults have diabetes 72% of adults are smokers Thank you to everyone who participated! How many households are harvesting traditional food? 62% of households harvested 78% want more traditional food.