Interests and Power As Drivers of Community Forestry Community of Drivers As Power and Interests Devkota Raj Rosan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annex B Report of the XI World Forestry Congress Technical

307 ■ Annex B Report of the XI World Forestry Congress Technical Session No. 27 Better Addressing Conflicts in Natural Resource Use through the Promotion of Participatory Management from Community to Policy Levels Topic 27 20 October Aspendos Auditorium Chairman: Untung Iskandar Moderators: Abdoulaye Kane and Marilyn Hoskins Technical Secretaries: Sedat Ayanoglu and Katherine Warner Special Paper: Claude Desloges and Michelle Gauthier Panel: Silvano Aureoles Conejo, Berken Feddersen, Abdoulaye Kane and Diane Rocheleau Outcome of the Session General The session focused on various dimensions of forest resource conflicts in the context of community forestry, and the strategies and tools devel- oped to address such conflicts. There is growing evidence that if forestry is to play a key role in sustainable development, forest-dependent communities must be fully involved in both the decision-making process and actions concerning the land and resources they inhabit and use. Sustainable forest development will not be achieved if it fails to (1) consider the needs and aspirations of rural and forest- dwelling communities and (2) acknowledge and address, in an appropriate and Community Forestry Unit ■ Integrating Conflict Management Considerations into National Policy Frameworks ■ 308 timely way, the conflict situations created by competition for the use of forest resources. Participatory forest resource management is crucial in this context as it creates an environment in which all actors can harmonize diverging views and may collaboratively plan and act together. Participatory management embraces how forest and tree resources should be used for the benefits of all partners, including the environment and future generations. Case studies presented at the session emphasized the need to clearly identify power relationships between forest-dependent communities and other actors such as government institutions, private enterprises and NGOs. -

Fifth World Forestry Congress

Proceedings of the Fifth World Forestry Congress VOLUME 1 RE University of Washington, Seattle, Washington United States of America August 29September 10, 1960 The President of the United States of America DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER Patron Fifth World Forestry Congress III Contents VOLUME 1 Page Chapter1.Summary and Recommendations of the Congress 1 Chapter 2.Planning for the Congress 8 Chapter3.Local Arrangements for the Congress 11 Chapter 4.The Congress and its Program 15 Chapter 5.Opening Ceremonies 19 Chapter6. Plenary Sessions 27 Chapter 7.Special Congress Events 35 Chapitre 1.Sommaire et recommandations du Congrès 40 Chapitre 2.Preparation des plans en vue du Congrès 48 Chapitre 3.Arrangements locaux en vue du Congrès 50 Chapitre 4.Le Congrès et son programme 51 Chapitre 5.Cérémonies d'ouverture 52 Chapitre 6.Seances plénières 59 Chapitre 7.Activités spéciales du Congrès 67 CapItullo1. Sumario y Recomendaciones del Congreso 70 CapItulo 2.Planes para el Congreso 78 CapItulo 3.Actividades Locales del Congreso 80 CapItulo 4.El Congreso y su Programa 81 CapItulo 5.Ceremonia de Apertura 81 CapItulo 6.Sesiones Plenarias 88 CapItulo 7.Actos Especiales del Congreso 96 Chapter8. Congress Tours 99 Chapter9.Appendices 118 Appendix A.Committee Memberships 118 Appendix B.Rules of Procedure 124 Appendix C.Congress Secretariat 127 Appendix D.Machinery Exhibitors Directory 128 Appendix E.List of Financial Contributors 130 Appendix F.List of Participants 131 First General Session 141 Multiple Use of Forest Lands Utilisation multiple des superficies boisées Aprovechamiento Multiple de Terrenos Forestales Second General Session 171 Multiple Use of Forest Lands Utilisation multiple des superficies boisées Aprovechamiento Multiple de Terrenos Forestales Iv Contents Page Third General Session 189 Progress in World Forestry Progrés accomplis dans le monde en sylviculture Adelantos en la Silvicultura Mundial Section I.Silviculture and Management 241 Sessions A and B. -

Ecological Information for Forestry Planning in Québec, Canada

Ecological Information for Forestry Planning in Québec, Canada Research Note Tabled at the XII World Forestry Congress – Québec, Canada 2003, by the Ministère des Ressources naturelles, de la Faune et des Parcs du Québec September 2003 Direction de la recherche forestière (Forest Research Branch) Ecological Information for Forestry Planning in Québec, Canada by Pierre Grondin1, Jean-Pierre Saucier2, Jacques Blouin3, Jocelyn Gosselin3 and André Robitaille4 Research Note Tabled at the XII World Forestry Congress – Québec, Canada 2003, by the Ministère des Ressources naturelles, de la Faune et des Parcs du Québec Ministère des Ressources naturelles, Ministère des Ressources naturelles, de la Faune et des Parcs du Québec (MRNFP) de la Faune et des Parcs du Québec (MRNFP) Direction de la recherche forestière (Forest Direction des inventaires forestiers (Forest Surveys Research Branch) Branch) 2700, rue Einstein 880, chemin Sainte-Foy Sainte-Foy (Québec) G1P 3W8 Québec (Québec) G1S 4X4 CANADA CANADA Telephone: (418) 643-7994 Telephone: (418) 627-8669 Fax: (418) 643-2165 Fax: (418) 646-1995 ou (418) 644-9672 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] www.forestrycongress.gouv.qc.ca [email protected] www.mrnfp.gouv.qc.ca andré[email protected] 1 Forest Engineer, M.Sc. 2 Forest Engineer, D.Sc. 3 Forest Engineer 4 Geomorphologist, M.Sc. MRNFP Research Note Abstract Québec is on the verge of becoming a dominant figure in the use of ecological information for forestry planning. Ecological information expresses ecological diversity. This diversity is presented in various ways, especially by the use of diagrams showing the forest dynamic that occurs among the various forest types observed, through a homogeneous combination of the soil and drainage (ecological type). -

Nepal Provinces Map Pdf

Nepal provinces map pdf Continue This article is about the provinces of Nepal. For the provinces of different countries, see The Province of Nepal नेपालका देशह Nepal Ka Pradesh haruCategoryFederated StateLocationFederal Democratic Republic of NepalDeitation September 20, 2015MumberNumber7PopulationsMemm: Karnali, 1,570,418Lard: Bagmati, 5,529,452AreasSmallest: Province No. 2, 9,661 square kilometers (3,730 sq m)Largest: Karnali, 27,984 square kilometers (10,805 sq.m.) GovernmentProvincial GovernmentSubdiviions Nepal This article is part of a series of policies and government Non-Trump Fundamental rights and responsibilities President of the Government of LGBT Rights: Bid Gia Devi Bhandari Vice President: Nanda Bahadur Pun Executive: Prime Minister: Hadga Prasad Oli Council of Ministers: Oli II Civil Service Cabinet Secretary Federal Parliament: Speaker of the House of Representatives: Agni Sapkota National Assembly Chair: Ganesh Prasad Timilsin: Judicial Chief Justice of Nepal: Cholenra Shumsher JB Rana Electoral Commission Election Commission : 200820152018 National: 200820132017 Provincial: 2017 Local: 2017 Federalism Administrative Division of the Provincial Government Provincial Assemblies Governors Chief Minister Local Government Areas Municipal Rural Municipalities Minister foreign affairs Minister : Pradeep Kumar Gyawali Diplomatic Mission / Nepal Citizenship Visa Law Requirements Visa Policy Related Topics Democracy Movement Civil War Nepal portal Other countries vte Nepal Province (Nepal: नेपालका देशह; Nepal Pradesh) were formed on September 20, 2015 under Schedule 4 of the Nepal Constitution. Seven provinces were formed by grouping existing districts. The current seven-provincial system had replaced the previous system, in which Nepal was divided into 14 administrative zones, which were grouped into five development regions. Story Home article: Administrative Units Nepal Main article: A list of areas of Nepal Committee was formed to rebuild areas of Nepal on December 23, 1956 and after two weeks the report was submitted to the government. -

CAY the 'WET TROIPICIAL FOREST SURVIVE?*- Public Disclosure Authorized by JOHN S

Conmonv. 7-or. Rev. 58 (3), 1979 CAY THE 'WET TROIPICIAL FOREST SURVIVE?*- Public Disclosure Authorized By JOHN S. SPEARST In this address, I intend to tackle a question about which much healthv controversy, but also considerable confusion has prevailed in the 1970s, namelv the implications of the continuing decline of the world's wet tropical forest area. I shall attempt to summarize what leading experts have saWi about this question during the 1970s, and to interpret, from a practicar forester's point of view, how their conclusions might alfect forestry management and investment decisions in the 1980s. The interpretations which I am making do not reflect an official view of the World Bank. In keeping with the objective of these annual Commonwealth Forestry Association meetings, they are primarily intended to provoke discussion. During the present decade, the rate of tropical deforestation has become a matter of interna- tional concern. The main questions being debated are: -How rapidly is the wet tropical forest being cut our and will it really disappear as some experts claim - wtchin the next 60 to 100 years? -Is there a viable land use alternative for the wvet- tropical forest lands? Public Disclosure Authorized -If the wet tropical forest were to disappear, what would be the global environmental and ecological consequences of its demise? -How will a further decline in the area of the tropical forests atfect future timber supplies? -Assuming that part of the wet tropical forests can be preserved, do natural forest manage- ment systems have any role or should they be replaced by more intensive plantation forestry? The rate of tropical forest destruction The extent to which leading world forestry experts agree on this question is hardly reassuring. -

A Brief Historical Perspective of Urban Forests in Canada As Published in Histoires Forestières Du Québec, Hiver 2015 Vol

Urban Forest Series, Volume I A Brief Historical Perspective of Urban Forests in Canada As published in Histoires forestières du Québec, Hiver 2015 Vol. 7, No 1, Pages 27-32 Michael Rosen, R.P.F. President, Tree Canada Introduction In recent years, a greater amount of interest has been in expressed in urban forests – partly as a result of increasing urbanization but also due to new threats including the invasive insect, emerald ash borer. This history reveals much about the country itself - the reluctance to move past the image of “hewers of wood” has made urban forestry a young “specialty field” within forestry in Canada. According to Dean (2015), European urban forests with their long lines of identical trees speak of the human control of na- ture while in North America, rows of street trees served to tame the wilderness as muddy frontier roads were “brought into line”. Others point to the “democratization of the automobile, densification, climate change and invasive insects” as powerful North American themes which pose the greatest threat to urban forests (Lévesque, 2014, p 6). Urban forests in Canada have been dominated by three themes: superficial support by the provincial and federal governments, individuals’ commitment to developing urban forests of excellence, and awareness and action fueled by natural disaster. Canada – the Urban People in a Forest Nation The world looks to Canada as a forest leader – and with good reason. With 417.6 million ha of forest (10% of the world) Canada leads in many of the standard, industrial forestry measures: “timber-pro- ductive forest land”, “allowable annual cut”, “area burned by forest fire”, and “area of certified forest”. -

Forests, Trees and Agroforestry: Livelihoods, Landscapes and Governance

CGIAR Research Program 6 Forests, Trees and Agroforestry: Livelihoods, Landscapes and Governance Proposal February 2011 CGIAR Research Program 6 Forests, Trees and Agroforestry: Livelihoods, Landscapes and Governance Proposal February 2011 Table of Contents Abbreviations vi Acknowledgements xvi Executive Summary xvii 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Setting the scene 1 1.2 Conceptual framework 7 1.3 The challenges 10 1.4 Vision of success 15 1.5 Strategy for impact 17 1.6 Innovation 20 1.7 Comparative advantage of CGIAR centers in leading this effort 22 1.8 Proposal road map 23 2. Research Portfolio 25 2.1 Component 1: Smallholder production systems and markets 28 2.2 Component 2: Management and conservation of forest and tree resources 60 2.3 Component 3: Landscape management for environmental services, biodiversity conservation and livelihoods 91 2.4 Component 4: Climate change adaptation and mitigation 120 2.5 Component 5: Impacts of trade and investment on forests and people 160 3. Cross-cutting Themes 189 3.1 Gender 189 3.2 Partnerships 200 3.3 Capacity strengthening 208 4. Program Support 215 4.1 Communications and knowledge sharing in CRP6 215 4.2 Monitoring and evaluation for impact 224 4.3 Program management 230 5. Budget 241 5.1 Overview 241 5.2 Assumptions and basis of projections 243 5.3 Composition 247 5.4 Resource allocation 248 Annexes 251 Annex 1. Descriptions of CGIAR centers 251 Annex 2. Consultation process 253 Annex 3. Linkages with other CRPs 255 Annex 4. Sentinel landscapes 262 Annex 5. Assumptions and evidence used to develop 10-year impact projections 274 Annex 6 Statements of Support 279 Annex 7. -

Strategies for Improving the Effectiveness of Asia-Pacific Forestry Research for Sustainable Development

Strategies for Improving the Effectiveness of Asia-Pacific Forestry Research for Sustainable Development Workshop Report* by Allen L. Lundgren Lawrence S. Hamilton Napoleon T. Vergara August 1986 3apers and discussion group reports presented at a workshop held at the East-West Center, :h 1986, by the East-West Environment and Policy Institute, Honolulu, Hawaii, USA. CONTENTS List of Tables and Exhibits iii Foreword v " Acknowledgments vii Executive Summary ix Introduction 1 Objectives and Scope of the Workshop 2 In-Country Forestry Research 2 Current Research 3 Research Priorities 8 Needs of Forestry Research Organizations 8 Region wide Forestry Development Initiatives with Research Implications 9 International Organizations 9 Regional Organizations 13 National Organizations 14 Nongovernmental Organization 16 International Conferences 16 Reflections and Conclusions on Forestry Initiatives and Research Implications 16 Summary of Discussion: Future Directions of Forestry Research 18 Comments by Rapporteurs 18 Some New Emphases in Forestry Research 22 Social Science 22 r Biotechnology 23 Participatory Action Research 24 Improving the Effectiveness of Forestry Research 24 Impediments to Effective Research 24 Comments by Rapporteurs 24 Research Strategy Priorities: Some Personal Views .29 A Word of Caution 30 Activities Highlighted for Immediate Action 31 Establish a Pacific Islands Regional Forestry Information Council 31 Include Pacific Islands in the Tropical Forestry Action Plan 32 Establish an ASEAN Social Forestry Network 32 Implement -

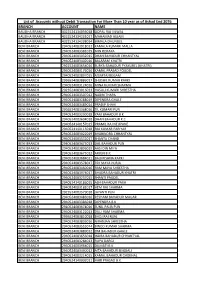

Branch Account Name

List of Accounts without Debit Transaction For More Than 10 year as of Ashad End 2076 BRANCH ACCOUNT NAME BAUDHA BRANCH 4322524134056018 GOPAL RAJ SILWAL BAUDHA BRANCH 4322524134231017 MAHAMAD ASLAM BAUDHA BRANCH 4322524134298014 BIMALA DHUNGEL BENI BRANCH 2940524083918012 KAMALA KUMARI MALLA BENI BRANCH 2940524083381019 MIN ROKAYA BENI BRANCH 2940524083932015 DHAN BAHADUR CHHANTYAL BENI BRANCH 2940524083402016 BALARAM KHATRI BENI BRANCH 2922524083654016 SURYA BAHADUR PYAKUREL (KHATRI) BENI BRANCH 2940524083176016 KAMAL PRASAD POUDEL BENI BRANCH 2940524083897015 MUMTAJ BEGAM BENI BRANCH 2936524083886017 SHUSHIL KUMAR KARKI BENI BRANCH 2940524083124016 MINA KUMARI SHARMA BENI BRANCH 2923524083016013 HASULI KUMARI SHRESTHA BENI BRANCH 2940524083507012 NABIN THAPA BENI BRANCH 2940524083288019 DIPENDRA GHALE BENI BRANCH 2940524083489014 PRADIP SHAHI BENI BRANCH 2936524083368016 TIL KUMARI PUN BENI BRANCH 2940524083230018 YAM BAHADUR B.K. BENI BRANCH 2940524083604018 DHAN BAHADUR K.C BENI BRANCH 2940524140157015 PRAMIL RAJ NEUPANE BENI BRANCH 2940524140115018 RAJ KUMAR PARIYAR BENI BRANCH 2940524083022019 BHABINDRA CHHANTYAL BENI BRANCH 2940524083532017 SHANTA CHAND BENI BRANCH 2940524083475013 DAL BAHADUR PUN BENI BRANCH 2940524083896019 AASI DIN MIYA BENI BRANCH 2940524083675012 ARJUN B.K. BENI BRANCH 2940524083684011 BALKRISHNA KARKI BENI BRANCH 2940524083578017 TEK MAYA PURJA BENI BRANCH 2940524083460016 RAM MAYA SHRESTHA BENI BRANCH 2940524083974017 BHADRA BAHADUR KHATRI BENI BRANCH 2940524083237015 SHANTI PAUDEL BENI BRANCH 2940524140186015 -

Global Perspectives on Indigenous Peoples' Forestry

GLOBAL PERSPECTIVES ON INDIGENOUS PEOPLES’ FORESTRY: LINKING COMMUNITIES, COMMERCE AND CONSERVATION Proceedings of the International Conference Vancouver, Canada June 4-6, 2002 Global Perspective on Indigenous Forestry: Linking Communities, Commerce and Conservation 1 Conference Proceedings—June 4-6 2002 Vancouver, Canada __________________________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE ........................................................................................................................... 4 BACKGROUND AND RATIONALE ............................................................................... 4 SUMMARY OF PRESENTATIONS ................................................................................. 7 Tuesday, June 4, 2002......................................................................................................... 7 SESSION 1:THE STATUS AND FUTURE OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES’ FORESTRY: GLOBAL AND REGIONAL PERSPECTIVES......................................7 David Kaimowitz, Making Forests Work For Communities ...................................... 7 Ed John, Legal Issues and Global Processes.............................................................. 8 Miriam Jorgensen, Beyond Treaties: Lessons for Community Economic Development................................................................................................................ 8 SESSION 2:ISSUES AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR INDIGENOUS FORESTRY......9 Harry Bombay, Issues and Opportunities for Indigenous Forestry -

COFO Sessions

COFO sessions Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday 23 June 2014 24 June 2014 25 June 2014 26 June 2014 27 June 2014 09.00 Side events Side events Side events Side events 10.00 Plenary Hall Red Room Red Room Red Room Green Room TH Opening Ceremony COFO22/4 Heads of Forestry dialogue: Enhancing Heads of Forestry dialogue: Item 6.7. Progress in Statutory International Wildland Fire Conference WFW policy implementation to foster Zero Illegal 10:00 Bodies and Key Partnerships Keynote speeches socioeconomic benefits Deforestation Challenge Item 6.8. Decisions and Recommendations of FAO Bodies of XIV World Forestry Congress 11.00 Item 4.1. Policy Measures to Sustain Item 5.3. The Zero Illegal Deforestation Item 1. Opening of the Session Interest to the Committee 10:20 and Enhance Forest Benefits Challenge Item 2. Adoption of the Agenda Item 7.2. Reducing Emissions from Item 5.1. Forests and the Sustainable Item 6.1. Progress Report on the Deforestation and Forest World Parks Congress Item 3. Election of Officers Development Goals Implementation of the Degradation, and the Climate 11.50 Recommendations of past Sessions of Item 4. State of the World's Forests Item 5. 5. The State of the World's Summit the Committee and the Multi-Year 2014: Enhancing the socioeconomic Forest Genetic Resources and the Global Green Room Austria Room Programme of Work (MYPOW) Item 7.3a Enhancing Work on benefits from forests Plan of Action for the Conservation, Immediate Plan of REDD+ and Sustainable Boreal Forests Sustainable use and Development of Item 6.2. -

Forest Industry Lecture Presented

SPACE, TIME AND PERSPECTIVES IN FORESTRY' KENNETH A. ARMSON2 Forest Industry Lecturer Forestry Program The University of Alberta November 1981 FOREST INDUSTRY LECTURE SERIES NO. 8 'Forest Industry Lecture presented at the University of Alberta, November 26, 1981 'Chief Forester, Forest Resources Group, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Toronto 1 THE FOREST INDUSTRY LECTURES Forest industry in northwestern Canada is cooperating with Alberta Energy and Natural Resources to provide funds to enrich the Forestry Program of the Faculty of Agriculture and Forestry at the University of Alberta through sponsorship of noteworthy speakers. The Forest Industry Lecture Series was started during the 1976-77 term as a seminar course. Desmond I. Crossley and Maxwell T. MacLaggan presented the first series of lectures. The contribution of these two noted Canadian foresters is greatly appreciated. Subsequent speakers in the series have visited for periods of up to a week, with all visits highlighted by a major public address. It has indeed been a pleasure to host such individuals as C. Ross Silversides, W. Gerald Burch, Gustaf Siren, Kenneth F.S. King, F.L.C. Reed, Gene Namkoong, and Roger Simmons. The subjects of their talks are listed on the last page. This paper contains Mr. Kenneth A. Armson's major public address given on 26 November 1981. 2 We would like to take this opportunity to express our thanks again to the sponsors of this program — we appreciate very much their willing and sustained support: Alberta Forest Products Association - Edmonton British Columbia Forest Products Ltd. - Vancouver North Canadian Forest Industries Ltd. - Grande Prairie Prince Albert Pulpwood Ltd.