Nepal's Political Rites of Passage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nepal Provinces Map Pdf

Nepal provinces map pdf Continue This article is about the provinces of Nepal. For the provinces of different countries, see The Province of Nepal नेपालका देशह Nepal Ka Pradesh haruCategoryFederated StateLocationFederal Democratic Republic of NepalDeitation September 20, 2015MumberNumber7PopulationsMemm: Karnali, 1,570,418Lard: Bagmati, 5,529,452AreasSmallest: Province No. 2, 9,661 square kilometers (3,730 sq m)Largest: Karnali, 27,984 square kilometers (10,805 sq.m.) GovernmentProvincial GovernmentSubdiviions Nepal This article is part of a series of policies and government Non-Trump Fundamental rights and responsibilities President of the Government of LGBT Rights: Bid Gia Devi Bhandari Vice President: Nanda Bahadur Pun Executive: Prime Minister: Hadga Prasad Oli Council of Ministers: Oli II Civil Service Cabinet Secretary Federal Parliament: Speaker of the House of Representatives: Agni Sapkota National Assembly Chair: Ganesh Prasad Timilsin: Judicial Chief Justice of Nepal: Cholenra Shumsher JB Rana Electoral Commission Election Commission : 200820152018 National: 200820132017 Provincial: 2017 Local: 2017 Federalism Administrative Division of the Provincial Government Provincial Assemblies Governors Chief Minister Local Government Areas Municipal Rural Municipalities Minister foreign affairs Minister : Pradeep Kumar Gyawali Diplomatic Mission / Nepal Citizenship Visa Law Requirements Visa Policy Related Topics Democracy Movement Civil War Nepal portal Other countries vte Nepal Province (Nepal: नेपालका देशह; Nepal Pradesh) were formed on September 20, 2015 under Schedule 4 of the Nepal Constitution. Seven provinces were formed by grouping existing districts. The current seven-provincial system had replaced the previous system, in which Nepal was divided into 14 administrative zones, which were grouped into five development regions. Story Home article: Administrative Units Nepal Main article: A list of areas of Nepal Committee was formed to rebuild areas of Nepal on December 23, 1956 and after two weeks the report was submitted to the government. -

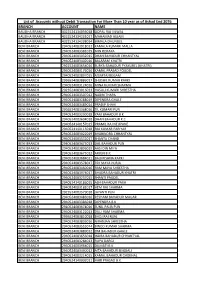

Branch Account Name

List of Accounts without Debit Transaction For More Than 10 year as of Ashad End 2076 BRANCH ACCOUNT NAME BAUDHA BRANCH 4322524134056018 GOPAL RAJ SILWAL BAUDHA BRANCH 4322524134231017 MAHAMAD ASLAM BAUDHA BRANCH 4322524134298014 BIMALA DHUNGEL BENI BRANCH 2940524083918012 KAMALA KUMARI MALLA BENI BRANCH 2940524083381019 MIN ROKAYA BENI BRANCH 2940524083932015 DHAN BAHADUR CHHANTYAL BENI BRANCH 2940524083402016 BALARAM KHATRI BENI BRANCH 2922524083654016 SURYA BAHADUR PYAKUREL (KHATRI) BENI BRANCH 2940524083176016 KAMAL PRASAD POUDEL BENI BRANCH 2940524083897015 MUMTAJ BEGAM BENI BRANCH 2936524083886017 SHUSHIL KUMAR KARKI BENI BRANCH 2940524083124016 MINA KUMARI SHARMA BENI BRANCH 2923524083016013 HASULI KUMARI SHRESTHA BENI BRANCH 2940524083507012 NABIN THAPA BENI BRANCH 2940524083288019 DIPENDRA GHALE BENI BRANCH 2940524083489014 PRADIP SHAHI BENI BRANCH 2936524083368016 TIL KUMARI PUN BENI BRANCH 2940524083230018 YAM BAHADUR B.K. BENI BRANCH 2940524083604018 DHAN BAHADUR K.C BENI BRANCH 2940524140157015 PRAMIL RAJ NEUPANE BENI BRANCH 2940524140115018 RAJ KUMAR PARIYAR BENI BRANCH 2940524083022019 BHABINDRA CHHANTYAL BENI BRANCH 2940524083532017 SHANTA CHAND BENI BRANCH 2940524083475013 DAL BAHADUR PUN BENI BRANCH 2940524083896019 AASI DIN MIYA BENI BRANCH 2940524083675012 ARJUN B.K. BENI BRANCH 2940524083684011 BALKRISHNA KARKI BENI BRANCH 2940524083578017 TEK MAYA PURJA BENI BRANCH 2940524083460016 RAM MAYA SHRESTHA BENI BRANCH 2940524083974017 BHADRA BAHADUR KHATRI BENI BRANCH 2940524083237015 SHANTI PAUDEL BENI BRANCH 2940524140186015 -

Naravane Visit a Positive Step to Repair Ties but Has Little to Do with Boundary Dispute, Experts

WITHOUT F EAR OR FAVOUR Nepal’s largest selling English daily Vol XXVIII No. 243 | 8 pages | Rs.5 O O Printed simultaneously in Kathmandu, Biratnagar, Bharatpur and Nepalgunj 34.4 C 0.5 C Friday, October 30, 2020 | 14-07-2077 Bhairahawa Jumla POST PHOTO: DEEPAK KC Mountains on the Kathmandu horizon are seen in this view captured from Chobhar on a clear autumn day. Naravane visit a positive step to No risk communication strategy yet as repair ties but has little to do with Covid-19 infections and death toll soar ARJUN POUDEL those outside welcomed the decision, “In medicine, students are taught KATHMANDU, OCT 29 saying that the daily count of corona- ‘to do no harm’,” a doctor at the minis- virus infections and resulting deaths, try told the Post. “People were infuri- boundary dispute, experts say The Health Ministry has stopped daily along with advisories related to the ated at the way messages were given Covid-19 briefings starting Thursday, pandemic had enraged people as the in the daily briefings, even if they and adopted a biweekly reporting—on briefings carried nothing, reminding were correct and scientific. We were Indian Army chief is arriving in Kathmandu next week amid frosty relations between Nepal Sundays and Wednesdays. the general public of the government’s actually doing more harm than good.” Doctors within the ministry and failure to contain the pandemic. >> Continued on page 2 and India and on the heels of the controversy over the trip of a top Delhi spy last week. ANIL GIRI Naravane’s visit will now take place KATHMANDU, OCT 29 on the heels of the controversy over the Oli-Goel meeting. -

Infusedinfused

fdh l’ldddbl l InfusedInfused NEPAL’SEthnicitiesEthnicities Interlaced AND Indivisible Gauri Nath Rimal SOCIAL MOSAIC End poverty. Together. Infused Ethnicities NEPAL’S Interlaced AND Indivisible SOCIAL MOSAIC Copyright: © 2007 Gauri Nath Rimal and Institute for Social and Environmental Transition-Nepal (ISET-N) The material in this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit uses, without prior written permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. The author would appreciate receiving a copy of any product which uses this publication as a source. This book has received partial funding support from Actionaid Nepal for printing. Citation: Rimal, G.N., 2007: Infused Ethnicities: Nepal’s Interlaced and Indivisible Social Mosaic, Institute for Social and Environmental Transition-Nepal, Kathmandu. ISBN: 978-99946-2-577-2 Printed by: Digiscan, June 2007, Kathmandu Nepal Price: NRs. 600/- Content Foreword iv Preface v Proposal for a Federated Nepal 1 The Context 8 About Maps 9 The Issue of Representation 42 The Larger Picture, the Future 49 Annexes 51-64 Annex 1 52 Annex 2 54 Annex 3 55 Annex 4 56 Annex 5 57 Annex 6 58 Annex 6 (Continued) 59 Annex 7A 60 Annex 7B 61 Annex 8 62 Annex 9 62 Annex 10 63 Annex 11 64 Bibliography 67 Acknowledgement 72 Foreword Through a process of political and administrative devolution Nepal is moving ahead to create a participatory, inclusive, egalitarian society with good governance and rule of law. Many ethnic groups with various cultural, linguistics and religious background live in the country’s plains, valleys, hills and mountains. -

Interests and Power As Drivers of Community Forestry Community of Drivers As Power and Interests Devkota Raj Rosan

“The concept of Community forestry promises to bring the forces of the local Rosan Raj Devkota forest users into a joint effort to maintain sustainable forests. The analysis shown in Devkota’s PhD thesis refers to the limitations of this concept drawn by powerful stakeholders. The theoretical sound and empirical rich analysis Interests and Power as provides the information needed to improve community forestry by a realistic Drivers of Community Forestry power strategy in practice.” - Prof. Dr. Max Krott, Chair of Forest and Nature Conservation Policy A Case Study of Nepal Georg-August-University Goettingen Rosan Raj Devkota Interests and Power as Drivers of Community Forestry Community of Drivers as Power and Interests Devkota Raj Rosan ISBN 978-3-941875-87-6 Universitätsdrucke Göttingen Universitätsdrucke Göttingen Rosan Raj Devkota Interests and Power as Drivers of Community Forestry This work is licensed under the Creative Commons License 3.0 “by-nd”, allowing you to download, distribute and print the document in a few copies for private or educational use, given that the document stays unchanged and the creator is mentioned. You are not allowed to sell copies of the free version. erschienen in der Reihe der Universitätsdrucke im Universitätsverlag Göttingen 2010 Rosan Raj Devkota Interests and Power as Drivers of Community Forestry A Case Study of Nepal Universitätsverlag Göttingen 2010 Bibliographische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliographie; detaillierte bibliographische Daten sind im Internet über <http://dnb.ddb.de> abrufbar. Global Forest Decimal Classification: 922.2, 906 Centre for Tropical and Subtropical Agriculture and Forestry (CeTSAF)- Tropenzentrum Georg-August-Universität Göttingen Büsgenweg 1 37077 Göttingen Address of the Author Rosan Raj Devkota e-mail: [email protected] This work is protected by German Intellectual Property Right Law. -

Nepal's Political Rites of Passage

NEPAL’S POLITICAL RITES OF PASSAGE Asia Report N°194 – 29 September 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 A. TURBULENT TRANSITIONS ........................................................................................................... 2 B. POLARISED PERSPECTIVES ........................................................................................................... 2 C. QUESTIONS AND CULTURES ......................................................................................................... 3 II. THE WAR THAT WAS ................................................................................................... 4 A. PEACE, PROCESS .......................................................................................................................... 4 1. The compulsion to collaborate ..................................................................................................... 4 2. Unfinished business ..................................................................................................................... 5 B. STRUCTURAL TRANSFORMATIONS ............................................................................................... 6 1. Entering the game ....................................................................................................................... -

Sr. No. Boid Name Bankacnum Bankname Reject Reason 1 1301250000055059 AADESH CHAUDHARY 00902136040 Siddhartha Bank Ltd.-Patan Branch Account Freezed

VIJAYA LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA SANSTHA LTD. Dividend Rejected List as of 01 Nov, 2019 ( F.Y. 2073/074) Sr. No. BoId Name BankAcNum BankName Reject Reason 1 1301250000055059 AADESH CHAUDHARY 00902136040 Siddhartha Bank Ltd.-Patan Branch Account Freezed. 2 1301120000428514 AADHYA SHARMA 242252410357201 Machhapuchhre Bank Ltd.-Baluwatar Branch Account Doesnot Exists. 3 1301120000428514 AADHYA SHARMA 242252410357201 Machhapuchhre Bank Ltd.-Baluwatar Branch Account Doesnot Exists. 4 1301120000313002 AARADHYA SHRESTHA 067010006305 Global IME Bank Ltd.-Kuleshwor Branch Account Doesnot Exists. 5 1301500000042092 AARATI RANJIT 06821500419504000001 NMB Bank Ltd.-Durbarmarg Branch Invalid Status. Transaction not allowed. 6 1301500000042092 AARATI RANJIT DARSHANDHARI 06821500419504000001 NMB Bank Ltd.-Durbarmarg Branch Invalid Status. Transaction not allowed. 7 1301060000046071 AARAVI POUDEL 0240000100CS Citizens Bank International Ltd.-Kapan Branch Account Doesnot Exists. 8 1301090000200831 AARUSH SHARMA 001005133203193 Everest Bank Ltd.-Baneshwor Branch Account Doesnot Exists. 9 1301130000038944 AASAMAYA MAHARJAN 0650050012447 Deva Bikas Bank Limited.-Madi Branch Account Doesnot Exists. 10 1301280000063139 AASHARA MANANDHAR 0600707275214001 Sunrise Bank Ltd.-Khusibu Branch Account Doesnot Exists. 11 1301300000011991 AASHISH SHAH 0550001594SR Century Commercial Bank Limited.-Manbhawan BranchAccount 2 Closed. 12 1301310000105521 AASHNA SHRESTHA 18H020886NPR001 NIC Asia Bank Ltd.- Boudha Branch Account Doesnot Exists. 13 1301070000029057 AASHRAY MAN TULADHAR -

Ibn Approves Investment Worth Npr 185.43 Billion 3

IBN DISPATCH | YEAR: 4 | ISSUE: 8 | VOLUME: 44 | BHADRA 2077 (AUGUST-SEPTEMBER 2020) 1 MONTHLY NEWSLETTER OF OIBN IBN DISPATCHYEAR: 4 | ISSUE: 8 | VOLUME: 44 | BHADRA 2077 (AUGUST-SEPTEMBER 2020) IBN 44th Board Meeting HYDROPOWER CEMENT PROJECTS PROJECTS 78.65 NPR Billion 32.50 28.06 NPR Billion NPR Billion 13.57 15.05 NPR Billion 10.31 NPR Billion NPR Billion 6.30 NPR Billion Upper Kaligandaki Isuwa Khola Myagdi Khola Ankhu Khola Dang Samrat Marshyangdi-2 Gorge Cement Cement IBN APPROVES INVESTMENT WORTH NPR 185.43 BILLION 3 CEO BHATTA TAKES OFFICE OIBN STARTS HANDOVER OF AGRO 4 PROJECTS TO PROVINCES 6 OIBN interacts with MPs representing Palpa district .............. 5 Land acquisition process moving smoothly for Arun-3 Transmission Lines..................................................................... 10 OIBN welcomes and bids farewell to senior officials ............. 8 Project activities, IBN services continue amid the COVID crisis. 11 2 IBN DISPATCH | YEAR: 4 | ISSUE: 8 | VOLUME: 44 | BHADRA 2077 (AUGUST-SEPTEMBER 2020) INVESTO GRAPH 5 4 1 2 3 TOP FDI HOST COUNTRIES 2020 UNITED 246 141 92 84 78 1STATES BILLION USD 2CHINA BILLION USD 3SINGAPORE BILLION USD 4NETHERLANDS BILLION USD 5IRELAND BILLION USD 5 2 4 2 1 3 TOP FDI HOME COUNTRIES 2020 UNITED 125 2 STATES BILLION USD 227 125 117 99 77 1JAPAN BILLION USD 2NETHERLANDS BILLION USD 3CHINA BILLION USD 4GERMANY BILLION USD 5 CANADA BILLION USD Data Source: World Investment Report, 2020 / UNCTAD IBN DISPATCH | YEAR: 4 | ISSUE: 8 | VOLUME: 44 | BHADRA 2077 (AUGUST-SEPTEMBER 2020) 3 IBN APPROVES FDI WORTH NPR 185.43 BILLION IBN 44th Board Meeting KATHMANDU: The 44th meeting of Investment for completing the detailed feasibility of the following Board Nepal (IBN) was held in Baluwatar under the projects: China-Nepal Friendship Industrial Park in chairmanship of the Right Honorable Prime Minister Damak, Muktinath Cable Car, Multimodal Logistics and Chairman of IBN Mr. -

Baluwatar Keeps Mum Over Oli's Status Even After His Close Aides Tested Positive for Covid-19

WITHOUT F EAR OR FAVOUR Nepal’s largest selling English daily Vol XXVIII No. 223 | 8 pages | Rs.5 O O Printed simultaneously in Kathmandu, Biratnagar, Bharatpur and Nepalgunj 34.6 C 6.9 C Monday, October 05, 2020 | 19-06-2077 Nepalgunj Jumla Why Govinda KC’s demands matter even more today as country battles the pandemic Covid-19 has exposed Nepal’s fragile health system and the fasting doctor’s demands for years have been aimed at making health care services accessible to all. BINOD GHIMIRE KATHMANDU, OCT 4 Dr Govinda KC’s 19th fast-unto-death entered its 21st day on Sunday. There has been no word from the govern- ment, except a token call to “end the hunger strike”. The Oli administration has not only adopted a nonchalant attitude POST PHOTO towards KC’s hunger strike and his Dr KC has staged 19 hunger strikes so far. demands but has also made its disdain for the 63-year-old doctor public. has exposed our fragile health care Exactly what it has been doing with system,” said Dr Jiwan Kshetry, a the coronavirus pandemic. vocal supporter of KC who also writes Civil society members say the gov- extensively on health care issues. ernment’s failure to respond to the “Most of KC’s demands revolve pandemic effectively is exactly what around ensuring that people have easy KC had been warning of for years. access to health services.” Nine months into the pandemic, the KC’s demands this time include government has given up on its fight establishing one government medical against Covid-19. -

Nepal Communist Party's Fragile Unity Falls Apart

WI THOUT F EAR O R F A V O U R Nepal’s largest selling English daily Vol XXVIII No. 295 | 8 pages | Rs.5 O O Printed simultaneously in Kathmandu, Biratnagar, Bharatpur and Nepalgunj 25.4 C -3.6 C Wednesday, December 23, 2020 | 08-09-2077 Dharan Jumla Nepal Communist Party’s fragile unity falls apart Factions led by Oli and Dahal are in bid to wrest control of the party, as both claim to have majority members on their side. MAY 16 Five- MAY 29 Dahal JULY third week Mid-AUG to mid-SEP NOV 20 Oli MARCH 4 point agree- makes public Dahal and Nepal Agreement between and Dahal Oli under- ment for party the agreement reach a written Dahal and Nepal; Nepal reach agree- JAN 26 Agni goes kid- Mid-JUNE to APRIL 20 unification between him agreement to relegated to fourth ment: Oli to Sapkota ney trans- SEP 5 Internal JAN second week mid-JULY Dahal lead the gov- Government MAY 17 Then and Oli to run remove Oli as rank; Nepal presents a elected as plant conflict surfac- Five Secretariat and Nepal unite Mid-OCT to mid-NOV ernment, issues ordinanc- CPN-UML and the government both prime min- note of dissent; Oli and the speaker es, Dahal member close to accusing Oli of AUG 16 Bamdev Dahal demands Dahal to run es related to the CPN (Maoist in turns ister and party Nepal have a heated of the announces Dahal form running the Gautam proposed implementation of the party as Constitutional 2018 Centre) unite 2019 chair debate 2020 Lower changes in ‘Dhobighat government as as party’s vice- the deal to make him executive Council and House ministers alliance’ per -

Nepal's Faltering Peace Process

NEPAL’S FALTERING PEACE PROCESS Asia Report Nº163 – 19 February 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS .................................................i I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................1 II. CONSENSUS OR CONFLICT? ......................................................................................2 A. WHAT’S LEFT OF THE PEACE PROCESS?.......................................................................................2 B. THE MAOIST-LED GOVERNMENT: IN OFFICE BUT NOT IN POWER? ..............................................3 C. OLD NEPAL: ALIVE AND WELL....................................................................................................5 D. THE RISKS OF FAILURE................................................................................................................6 III. PEACE PARTNERS AT ODDS.......................................................................................8 A. THE MAOISTS: BRINGING ON THE REVOLUTION?.........................................................................8 B. UNCERTAIN COALITION PARTNERS..............................................................................................9 C. THE OPPOSITION: REINVIGORATED, BUT FOR WHAT? ................................................................11 1. The Nepali Congress................................................................................................................. 11 2. The smaller parties ................................................................................................................... -

There May Not Be Enough Health Workers to Attend to Patients

WITHOUT F EAR OR FAVOUR Nepal’s largest selling English daily Vol XXVIII No. 225 | 8 pages | Rs.5 O O Printed simultaneously in Kathmandu, Biratnagar, Bharatpur and Nepalgunj 35.2 C 8.0 C Wednesday, October 07, 2020 | 21-06-2077 Nepalgunj Jumla Given its failure, Covid-19 Crisis Management Centre’s relevance in question The deputy prime minister-led centre’s role is limited to making recommendations to the Cabinet but they are often shot down by the prime minister. TIKA R PRADHAN and it ended without a proper decision. KATHMANDU, OCT 6 “After studying the situation, the committee has decided to seek propos- Before Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli als from different ministries,” said got admitted to Tribhuvan University Mahendra Guragain, member secre- Teaching Hospital for his second kid- tary of the centre, after that meeting. ney transplant on the evening of The proposals that he was referring March 2, he formed a high-level coor- to were on safety protocols to be fol- dination committee to prepare the lowed to check the spread of the virus. country for curbing the spread of the Incidentally, the day Guragain said coronavirus. that marked exactly six months since Deputy Prime Minister and Defence the Covid-19 Crisis Management Minister Ishwar Pokhrel headed it. Centre was formed. Then on March 29 when the country By the Centre member’s own admis- was on the sixth day of the nationwide sion, it has been a gross failure. lockdown, the Covid-19 Crisis “There is a tendency that the deci- Management Centre, also headed by sions of the Centre won’t be implement- the deputy prime minister, was formed ed,” a minister said after the meeting.