Armed Conflict and Peace Process in Nepal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Code Under Name Girls Boys Total Girls Boys Total 010290001

P|D|LL|S G8 G10 Code Under Name Girls Boys Total Girls Boys Total 010290001 Maiwakhola Gaunpalika Patidanda Ma Vi 15 22 37 25 17 42 010360002 Meringden Gaunpalika Singha Devi Adharbhut Vidyalaya 8 2 10 0 0 0 010370001 Mikwakhola Gaunpalika Sanwa Ma V 27 26 53 50 19 69 010160009 Phaktanglung Rural Municipality Saraswati Chyaribook Ma V 28 10 38 33 22 55 010060001 Phungling Nagarpalika Siddhakali Ma V 11 14 25 23 8 31 010320004 Phungling Nagarpalika Bhanu Jana Ma V 88 77 165 120 130 250 010320012 Phungling Nagarpalika Birendra Ma V 19 18 37 18 30 48 010020003 Sidingba Gaunpalika Angepa Adharbhut Vidyalaya 5 6 11 0 0 0 030410009 Deumai Nagarpalika Janta Adharbhut Vidyalaya 19 13 32 0 0 0 030100003 Phakphokthum Gaunpalika Janaki Ma V 13 5 18 23 9 32 030230002 Phakphokthum Gaunpalika Singhadevi Adharbhut Vidyalaya 7 7 14 0 0 0 030230004 Phakphokthum Gaunpalika Jalpa Ma V 17 25 42 25 23 48 030330008 Phakphokthum Gaunpalika Khambang Ma V 5 4 9 1 2 3 030030001 Ilam Municipality Amar Secondary School 26 14 40 62 48 110 030030005 Ilam Municipality Barbote Basic School 9 9 18 0 0 0 030030011 Ilam Municipality Shree Saptamai Gurukul Sanskrit Vidyashram Secondary School 0 17 17 1 12 13 030130001 Ilam Municipality Purna Smarak Secondary School 16 15 31 22 20 42 030150001 Ilam Municipality Adarsha Secondary School 50 60 110 57 41 98 030460003 Ilam Municipality Bal Kanya Ma V 30 20 50 23 17 40 030460006 Ilam Municipality Maheshwor Adharbhut Vidyalaya 12 15 27 0 0 0 030070014 Mai Nagarpalika Kankai Ma V 50 44 94 99 67 166 030190004 Maijogmai Gaunpalika -

The Document Was Created from a File "F:\Countries\Nepal\2017\Report

ELECTION OBSERVATION DELEGATION TO THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES AND PROVINCIAL ASSEMBLIES ELECTIONS IN NEPAL (26 November and 7 December 2017) Report by Neena Gill CBE, Head of the EP Delegation Annexes: A. List of participants and programme of the delegation B. European Parliament Election Observation Delegation Statement C. EU Election Observation Mission Preliminary findings and conclusions D. Press release by the EU EOM Introduction: Following an invitation from the Nepal authorities, the Conference of Presidents on 5 October 2017 authorised the sending of a delegation to observe the elections to the House of Representatives and provincial assemblies in Nepal. These elections were taking place in two phases on 26 November in the constituencies in the more mountainous districts and on 7 December in the remaining 45 constituencies. The European Parliament has always been a strong supporter of the process of democratic consolidation in Nepal following the civil war in the country in the early 2000s. It observed the elections in 2008 and 2013 and the sending of a further delegation was a sign of its ongoing commitment. EU financial assistance to Nepal has strengthened under the multiannual indicative programme for 2014-2020 which included support for democracy and good governance. Development aid amounts to €360 million, which is triple the amount for the previous budget period. At the constituent meeting on 19 October 2017 Ms Neena GILL CBE (S&D, UK) was elected head of the delegation that would observe both phases. For the first phase the delegation was also composed of Ivan STEFANEC (EPP, SK), Tomas ZDECHOVSKY (EPP, CZ), Norbert NEUSER (S&D, DE), Bernd LUCKE (ECR, DE), Javier NART (ALDE, ES), and Georg MAYER (ENF, AT). -

Kanchanpur District

District Transport Master Plan (DTMP) For Kanchanpur District ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Government of Nepal District Transport Master Plan (DTMP) of Kanchanpur District Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development Department of Local Infrastructure Development and Agricultural Roads (DOLIDAR) District Development Committee, Kanchanpur Volume I Final Report January. 2016 Prepared by: Project Research and Engineering Associates for the District Development Committee (DDC) and District Technical Office (DTO), with Technical Assistance from the Department of Local Infrastructure and Agricultural Roads (DOLIDAR), Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development and grant supported by DFID through Rural Access Programme (RAP3). District Transport Master Plan (DTMP) For Kanchanpur District ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Project Research and Engineering Associates 1 District Transport Master Plan (DTMP) For Kanchanpur District ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Project Research and Engineering Associates Lagankhel, Lalitpur Phone: 5539607 Email: [email protected] -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

Nepal Provinces Map Pdf

Nepal provinces map pdf Continue This article is about the provinces of Nepal. For the provinces of different countries, see The Province of Nepal नेपालका देशह Nepal Ka Pradesh haruCategoryFederated StateLocationFederal Democratic Republic of NepalDeitation September 20, 2015MumberNumber7PopulationsMemm: Karnali, 1,570,418Lard: Bagmati, 5,529,452AreasSmallest: Province No. 2, 9,661 square kilometers (3,730 sq m)Largest: Karnali, 27,984 square kilometers (10,805 sq.m.) GovernmentProvincial GovernmentSubdiviions Nepal This article is part of a series of policies and government Non-Trump Fundamental rights and responsibilities President of the Government of LGBT Rights: Bid Gia Devi Bhandari Vice President: Nanda Bahadur Pun Executive: Prime Minister: Hadga Prasad Oli Council of Ministers: Oli II Civil Service Cabinet Secretary Federal Parliament: Speaker of the House of Representatives: Agni Sapkota National Assembly Chair: Ganesh Prasad Timilsin: Judicial Chief Justice of Nepal: Cholenra Shumsher JB Rana Electoral Commission Election Commission : 200820152018 National: 200820132017 Provincial: 2017 Local: 2017 Federalism Administrative Division of the Provincial Government Provincial Assemblies Governors Chief Minister Local Government Areas Municipal Rural Municipalities Minister foreign affairs Minister : Pradeep Kumar Gyawali Diplomatic Mission / Nepal Citizenship Visa Law Requirements Visa Policy Related Topics Democracy Movement Civil War Nepal portal Other countries vte Nepal Province (Nepal: नेपालका देशह; Nepal Pradesh) were formed on September 20, 2015 under Schedule 4 of the Nepal Constitution. Seven provinces were formed by grouping existing districts. The current seven-provincial system had replaced the previous system, in which Nepal was divided into 14 administrative zones, which were grouped into five development regions. Story Home article: Administrative Units Nepal Main article: A list of areas of Nepal Committee was formed to rebuild areas of Nepal on December 23, 1956 and after two weeks the report was submitted to the government. -

Chronology of Major Political Events in Contemporary Nepal

Chronology of major political events in contemporary Nepal 1846–1951 1962 Nepal is ruled by hereditary prime ministers from the Rana clan Mahendra introduces the Partyless Panchayat System under with Shah kings as figureheads. Prime Minister Padma Shamsher a new constitution which places the monarch at the apex of power. promulgates the country’s first constitution, the Government of Nepal The CPN separates into pro-Moscow and pro-Beijing factions, Act, in 1948 but it is never implemented. beginning the pattern of splits and mergers that has continued to the present. 1951 1963 An armed movement led by the Nepali Congress (NC) party, founded in India, ends Rana rule and restores the primacy of the Shah The 1854 Muluki Ain (Law of the Land) is replaced by the new monarchy. King Tribhuvan announces the election to a constituent Muluki Ain. The old Muluki Ain had stratified the society into a rigid assembly and introduces the Interim Government of Nepal Act 1951. caste hierarchy and regulated all social interactions. The most notable feature was in punishment – the lower one’s position in the hierarchy 1951–59 the higher the punishment for the same crime. Governments form and fall as political parties tussle among 1972 themselves and with an increasingly assertive palace. Tribhuvan’s son, Mahendra, ascends to the throne in 1955 and begins Following Mahendra’s death, Birendra becomes king. consolidating power. 1974 1959 A faction of the CPN announces the formation The first parliamentary election is held under the new Constitution of CPN–Fourth Congress. of the Kingdom of Nepal, drafted by the palace. -

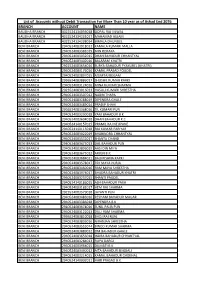

Branch Account Name

List of Accounts without Debit Transaction For More Than 10 year as of Ashad End 2076 BRANCH ACCOUNT NAME BAUDHA BRANCH 4322524134056018 GOPAL RAJ SILWAL BAUDHA BRANCH 4322524134231017 MAHAMAD ASLAM BAUDHA BRANCH 4322524134298014 BIMALA DHUNGEL BENI BRANCH 2940524083918012 KAMALA KUMARI MALLA BENI BRANCH 2940524083381019 MIN ROKAYA BENI BRANCH 2940524083932015 DHAN BAHADUR CHHANTYAL BENI BRANCH 2940524083402016 BALARAM KHATRI BENI BRANCH 2922524083654016 SURYA BAHADUR PYAKUREL (KHATRI) BENI BRANCH 2940524083176016 KAMAL PRASAD POUDEL BENI BRANCH 2940524083897015 MUMTAJ BEGAM BENI BRANCH 2936524083886017 SHUSHIL KUMAR KARKI BENI BRANCH 2940524083124016 MINA KUMARI SHARMA BENI BRANCH 2923524083016013 HASULI KUMARI SHRESTHA BENI BRANCH 2940524083507012 NABIN THAPA BENI BRANCH 2940524083288019 DIPENDRA GHALE BENI BRANCH 2940524083489014 PRADIP SHAHI BENI BRANCH 2936524083368016 TIL KUMARI PUN BENI BRANCH 2940524083230018 YAM BAHADUR B.K. BENI BRANCH 2940524083604018 DHAN BAHADUR K.C BENI BRANCH 2940524140157015 PRAMIL RAJ NEUPANE BENI BRANCH 2940524140115018 RAJ KUMAR PARIYAR BENI BRANCH 2940524083022019 BHABINDRA CHHANTYAL BENI BRANCH 2940524083532017 SHANTA CHAND BENI BRANCH 2940524083475013 DAL BAHADUR PUN BENI BRANCH 2940524083896019 AASI DIN MIYA BENI BRANCH 2940524083675012 ARJUN B.K. BENI BRANCH 2940524083684011 BALKRISHNA KARKI BENI BRANCH 2940524083578017 TEK MAYA PURJA BENI BRANCH 2940524083460016 RAM MAYA SHRESTHA BENI BRANCH 2940524083974017 BHADRA BAHADUR KHATRI BENI BRANCH 2940524083237015 SHANTI PAUDEL BENI BRANCH 2940524140186015 -

The Abolition of Monarchy and Constitution Making in Nepal

THE KING VERSUS THE PEOPLE(BHANDARI) Article THE KING VERSUS THE PEOPLE: THE ABOLITION OF MONARCHY AND CONSTITUTION MAKING IN NEPAL Surendra BHANDARI Abstract The abolition of the institution of monarchy on May 28, 2008 marks a turning point in the political and constitutional history of Nepal. This saga of constitutional development exemplifies the systemic conflict between people’s’ aspirations for democracy and kings’ ambitions for unlimited power. With the abolition of the monarchy, the process of making a new constitution for the Republic of Nepal has started under the auspices of the Constituent Assembly of Nepal. This paper primarily examines the reasons or causes behind the abolition of monarchy in Nepal. It analyzes the three main reasons for the abolition of monarchy. First, it argues that frequent slights and attacks to constitutionalism by the Nepalese kings had brought the institution of the monarchy to its end. The continuous failures of the early democratic government and the Supreme Court of Nepal in bringing the monarchy within the constitutional framework emphatically weakened the fledgling democracy, but these failures eventually became fatal to the monarchical institution itself. Second, it analyzes the indirect but crucial role of India in the abolition of monarchy. Third, it explains the ten-year-long Maoist insurgency and how the people’s movement culminated with its final blow to the monarchy. Furthermore, this paper also analyzes why the peace and constitution writing process has yet to take concrete shape or make significant process, despite the abolition of the monarchy. Finally, it concludes by recapitulating the main arguments of the paper. -

Distribution of Arsenic Biosand Filters in Rural Nepal

DISTRIBUTION OF ARSENIC BIOSAND FILTERS IN RURAL NEPAL SLOAN SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT APRIL 2004 THE G-LAB TEAM Basak Yildizbayrak, MBA 2004 Nikos Moschos, MBA 2004 Tamer Tamar, MBA 2004 Yann Le Tallec, Ph.D 2006 Acknowledgment: We would like to thank the Bergstrom Family Foundation for its support of this project. TABLE OF CONTENTS A. INTRODUCTION............................................................................................3 1. The Water Problem in Nepal and Arsenic Contamination............................................. 3 2. Project Scope.................................................................................................................. 3 3. Methodology ..................................................................................................................4 4. Important MIT contacts/lead people for various work streams ..................................... 4 B. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................................5 1. Short-Term Recommendations...................................................................................... 5 2. Long-Term Recommendations for Sustainable Filter Distribution ............................... 5 C. THE WORLD BANK PROJECT .....................................................................7 D. PRODUCT DESIGN AND UNIT COSTS.......................................................8 1. Existing Filters ............................................................................................................... 9 2. Alternative -

EBHR 37 Cover Page.Indd

56 EBHR-37 Minority Rights and Constitutional Borrowings in the Drafting of Nepal’s 1990 Constitution Mara Malagodi This article aims to investigate the reasons for and modalities of the rejection of the minority approach in Nepal’s 1990 Constitution-making experience.1 The analysis is conducted in light of the country’s post- Panchayat process of re-democratisation and vis-à-vis the high degree of socio-cultural diversity of the Nepali polity in which no group amounts to a numerical majority.2 The 1990 Constitution-making process was articulated in two phases: (a) the drafting of the document by the nine-member Constitution Recommendation Commission (CRC) between 31 May and 10 September 1990, and (b) the finalisation of the draft by a three-member Cabinet Committee, leading to the promulgation of the document on 9 November 1990.3 The expression ‘minority approach’ is employed here to indicate the specific array of choices made by Constitution-makers in designing state institutions reflective of a country’s socio-cultural diversity and giving 1 The present article is based on my presentation at the MIDEA workshop on Constitutionalism and Diversity held in Kathmandu, 22-24 August 2007 (see http://www.uni-bielefeld.de/ midea/whats%20new/previous_events.html). I am grateful to the MIDEA workshop’s organisers and participants for their insightful comments on my paper and to the EBHR reviewers for their detailed and perceptive observations which significantly helped improve my paper. My doctoral research in Nepal in 2006 and 2007 was supported by a generous grant from the University of London Central Research Fund in 2006. -

News Update from Nepal, June 9, 2005

News update from Nepal, June 9, 2005 News Update from Nepal June 9, 2005 The Establishment The establishment in Nepal is trying to consolidate the authority of the state in society through various measures, such as beefing up security measures, extending the control of the administration, dismantling the base of the Maoists and calling the political parties for reconciliation. On May 27 King Gyanendra in his address called on the leaders of the agitating seven-party alliance “to shoulder the responsibility of making all democratic in- stitutions effective through free and fair elections.” He said, “We have consistently held discussions with everyone in the interest of the nation, people and democracy and will continue to do so in the future. We wish to see political parties becoming popular and effective, engaging in the exercise of a mature multiparty democracy, dedicated to the welfare of the nation and people and to peace and good governance, in accordance with people’s aspirations.” Defending the existing Constitution of Nepal 1990 the King argued, “At a time when the nation is grappling with terrorism, the shared commitment and involvement of all political parties sharing faith in democracy is essential to give permanency to the gradually im- proving peace and security situation in the country.” He added, “Necessary preparations have already been initiated to hold these elections, and activate in stages all elected bodies which have suffered a setback during the past three years.” However, King Gy- anendra reiterated that the February I decision was taken to safeguard democracy from terrorism and to ensure that the democratic form of governance, stalled due to growing disturbances, was made effective and meaningful. -

Nepal One Hundred Days After Royal Takeover and Human Rights Crisis Deepens February 1– May 11, 2005

Nepal One Hundred Days after Royal Takeover and Human Rights Crisis Deepens February 1– May 11, 2005 12 May 2005 Published by Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUM-ASIA) This report is a compilation of contributions coming from different organizations and individuals, both within Nepal and outside. Due to security reasons, the names of the contributors, editors and their institutional affiliations are not disclosed. 2 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 1.0 INTRODUCTION 7 1.1 General overview of the country 7 1.1.1 Socio-political development 7 1.1.2 Human rights regime 9 1.1.2.1 Constitution of the Kingdom of Nepal 1990 9 1.1.2.2 International human rights instruments 12 2.0 GROSS VIOLATIONS OF HUMAN RIGHTS 14 2.1 An overview of the violation of human rights after the royal-military takeover 14 2.1.1 Restrictions on media 15 2.1.2 Restrictions on travel 16 2.1.3 Violations by the Maoists 16 2.2 Constitutional and legal issues 17 2.2.1. Accountability 17 2.2.2 State of emergency 17 2.2.3 Legal standing of Government 19 2.2.4. Suppression of dissent 19 2.3 State of emergency and international obligations 19 2.3.1 Pre-conditions for declaring a state of emergency 20 2.3.2 Notification under ICCPR Article 4 21 2.4 Judiciary and constitutional institutions under trial 22 2.4.1 Royal Commission for Corruption Control (RCCC) 23 2.4.2 Violation of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 24 2.4.3 Torture in detention 26 2.4.4 Judicial reluctance to engage in human rights protection 26 2.4.5 Militarization of the governance system