CHAPTER VII1 ALTHOUGH the Confusion of the Landing In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lessons in Leadership the Life of Sir John Monash GCMG, KCB, VD

Lessons in Leadership The Life of Sir John Monash GCMG, KCB, VD By Rolfe Hartley FIEAust CPEng EngExec FIPENZ Engineers Australia Sydney Division CELM Presentation March 2013 Page 1 Introduction The man that I would like to talk about today was often referred to in his lifetime as ‘the greatest living Australian’. But today he is known to many Australians only as the man on the back of the $100 note. I am going to stick my neck out here and say that John Monash was arguably the greatest ever Australian. Engineer, lawyer, soldier and even pianist of concert standard, Monash was a true leader. As an engineer, he revolutionised construction in Australia by the introduction of reinforced concrete technology. He also revolutionised the generation of electricity. As a soldier, he is considered by many to have been the greatest commander of WWI, whose innovative tactics and careful planning shortened the war and saved thousands of lives. Monash was a complex man; a man from humble beginnings who overcame prejudice and opposition to achieve great things. In many ways, he was an outsider. He had failures, both in battle and in engineering, and he had weaknesses as a human being which almost put paid to his career. I believe that we can learn much about leadership by looking at John Monash and considering both the strengths and weaknesses that contributed to his greatness. Early Days John Monash was born in West Melbourne in 1865, the eldest of three children and only son of Louis and Bertha. His parents were Jews from Krotoshin in Prussia, an area that is in modern day Poland. -

Bull Brothers – Robert and Henry

EMU PARK SOLDIERS OF WORLD WAR I – THE GREAT WAR FROM EMU PARK and SHIRE OF LIVINGSTONE The Bull Brothers – Robert and Henry Sergeant Robert Charles Bull (Service No. 268) of the 15th Infantry Battalion and 1st Battalion Imperial Camel Brigade Robert was born on 17th May 1895 in a railway camp at Boolburra, the 9th child and 3rd son to Henry and Maria (née Ferguson) Bull, both immigrants from the United Kingdom. Henry from Whaplode, Lincolnshire, arrived in Rockhampton in 1879 at the age of 19. Maria was from Cookstown, Tyrone, North Ireland, arrived in Maryborough, also in 1879 and also aged 19. Robert spent his early years at Bajool before joining the Railway Service as a locomotive cleaner. He enlisted in the Australian Imperial Forces (AIF) on 16 September 1914 at Emerald where he gave his age as 21 years & 4 months, when in fact he was only 19 years & 4 months. Private Bull joined ‘B’ Company of the 15th Infantry Battalion, 4th Brigade which formed the Australian and New Zealand Division when they arrived in Egypt. The 15th Infantry Battalion consisted on average of 29 Officers and 1007 Other Ranks (OR’s) and was broken up into the following sub units: Section Platoon Company Battalion Rifle section:- Platoon Headquarters Company Battalion 10 OR’s (1 Officer & 4 OR’s) Headquarters (2 Headquarters (5 Officers & 57 Officers & 75 OR’s) Lewis Gun Section:- 10 3 Rifle Sections and OR’s) OR’s and 1 Lewis gun Section 4 Companies 1 Light Machine Gun 4 Platoons He sailed for Egypt aboard the HMAT (A40) Ceramic on 22nd December 1914. -

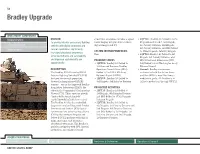

Bradley Upgrade

50 Bradley Upgrade INVESTMENT COMPONENT Modernization MISSION situational awareness includes a squad • 3QFY10: Bradley A3 fielded to Army To provide infantry and cavalry fighting leader display integrated into vehicle Prepositioned Stock 5, 3rd Brigade, Recapitalization vehicles with digital command and digital images and IC3. 1st Cavalry Division; 2nd Brigade, 1st Cavalry Division; and ODS fielded Maintenance control capabilities, significantly SYSTEM INTERDEPENDENCIES to 172nd Separate Infantry Brigade increased situational awareness, None • 4QFY10: Bradley A3 fielded to 1st enhanced lethality and survivability, Brigade, 1st Cavalry Division; and and improved sustainability and PROGRAM STATUS ODS Situational Awareness (ODS supportability. • 1QFY09: Bradley A3 fielded to SA) fielded to 81st Washington Army 1st Armored Division; Bradley National Guard DESCRIPTION Operation Desert Storm (ODS) • Current: Bradley conversions The Bradley M2A3 Infantry/M3A3 fielded to the 155th MS Army continue for both the Active Army Cavalry Fighting Vehicle (IFV/CFV) National Guard (ARNG) and the ARNG to meet the Army’s features two second-generation, • 1QFY09: Bradley A3 fielded to modularity goals; A3 Bradley is in forward-looking infrared (FLIR) 3rd Brigade, 3rd Infantry Division full-rate production through 3QFY11. sensors—one in the Improved Bradley Acquisition Subsystem (IBAS), the PROJECTED ACTIVITIES other in the Commander’s Independent • 1QFY10: Bradley A3 fielded to Viewer (CIV). These systems provide 1st Brigade, 4th Infantry Division; “hunter-killer -

History 119Th Infantry, 60Th Brigade, 30Th Division, U.S.A.Operations in Belgium and France, 1917-1919

History 119th Infantry, 60th Brigade 30th Division U. S. A. Operations in Belgium and France 1917-1919 TUritten at the request of the lPilmington Chamber of Commerce, and Published by that Organization in Honor of Col. John Uano. Metts and His Qallant Men and as a Contribution to American Historu Walter Clinton Jackson Library The University of North Carolina at Greensboro Special Collections & Rare Books World War I Pamphlet Collection Gift of Greensboro Public Library History 119th Infantry, 60th brigade 30th Diuision U. S. A. Operations in Belgium and France 1917^1919 IDritten at the request of the UJUmington Chamber of Commerce, and Published bu that Organization in Honor of Col. Jnhn UanB. Metis and His Qallant Men and as a Contribution to American Historu Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Lyrasis Members and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/history119thinfa00inconw — To the Parents and Friends, and, in Honor of Those Brave and Noble Men of the 119th Infantry, of Whom it Can Truly be Said That They Performed Their Duty Honorably and Gloriously. This History of the 119th Infantry, 60th Brigade, 30th Division, U. S. A., was compiled by Captain C. B. Conway, of Danville, Va., and Lieutenant George A. Shuford, of Ashe- ville, N. C. It was their effort to write only of Facts, that the records of the deeds of true and brave men may be given. To them is due the thanks and appreciation of the officers and men of the Regiment. Due to the loss of the list of the officers and the fact that a full and complete list cannot be published, the names of officers are not made a part of this record. -

ARMOR March-April 2008

The Professional Bulletin of the Armor Branch, Headquarters, Department of the Army, PB 17-08-2 Editor in Chief Features LTC SHANE E. LEE 6 Using Tactical Site Exploitation to Target the Insurgent Network Managing Editor by Michael Thomas CHRISTY BOURGEOIS 14 Human Terrain Mapping: A Critical First Step Commandant in Winning the Counterinsurgency Fight by Lieutenant Colonel Jack Marr, Major John Cushing, BG DONALD M. CAMPBELL, JR. Major Brandon Garner, and Captain Richard Thompson 19 How Information Operations Enable Combatant ARMOR (ISSN 0004-2420) is published bi- Commanders to Dominate Today’s Battlefi eld monthly by the U.S. Army Armor Center, ATTN: by Lieutenant Colonel Scott K. Fowler ATZK-DAS-A, Building 1109A, 201 6th Ave- nue, Ste 373, Fort Knox, KY 40121-5721. 22 Win the Battle – Lead to Peace Disclaimer: The information contained in AR- by Colonel Bruno Duhesme, French Army MOR represents the professional opinions of the authors and does not necessarily reflect 26 An Approach to Route Security the official Army or TRADOC position, nor by Captain Nicholas C. Sinclair does it change or supersede any information presented in other official Army publications. 33 Ground School XXI – The Next Step Official distribution is limited to one copy for in Combined Arms Simulation Training each armored brigade headquarters, ar mored by Colonel Robert Valdivia cavalry regiment headquarters, armor battal- ion headquarters, armored cavalry squadron 36 Predator Palace: Gaining a Foothold headquarters, reconnaissance squadron head- by Captain Peter J. Young Jr. quar ters, armored cavalry troop, armor com- pany, and motorized brigade headquarters of 43 Team Enabler: Combining Capabilities the United States Army. -

Understanding the First AIF: a Brief Guide

Last updated August 2021 Understanding the First AIF: A Brief Guide This document has been prepared as part of the Royal Australian Historical Society’s Researching Soldiers in Your Local Community project. It is intended as a brief guide to understanding the history and structure of the First Australian Imperial Force (AIF) during World War I, so you may place your local soldier’s service in a more detailed context. A glossary of military terminology and abbreviations is provided on page 25 of the downloadable research guide for this project. The First AIF The Australian Imperial Force was first raised in 1914 in response to the outbreak of global war. By the end of the conflict, it was one of only three belligerent armies that remained an all-volunteer force, alongside India and South Africa. Though known at the time as the AIF, today it is referred to as the First AIF—just like the Great War is now known as World War I. The first enlistees with the AIF made up one and a half divisions. They were sent to Egypt for training and combined with the New Zealand brigades to form the 1st and 2nd Divisions of the Australia and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC). It was these men who served on Gallipoli, between April and December 1915. The 3rd Division of the AIF was raised in February 1916 and quickly moved to Britain for training. After the evacuation of the Gallipoli peninsula, 4th and 5th Divisions were created from the existing 1st and 2nd, before being sent to France in 1916. -

Leaders Shaping Australia's Future

Leaders shaping Australia’s future “The privilege of education carries great responsibilities – it is given not for individual benefit alone, but to befit persons for the higher duties of citizenship and for roles of leadership in all fields...” General Sir John Monash GCMG KCB VD Image (right): John Monash, 1919 by James Quinn. Collection: National Portrait Gallery, Canberra. Gift of John Colin Monash Bennett, 2007. 1 2 Transforming Australia through inspired leadership 3 4 FoundationWe invite you Timeline to join us… • Inaugural meeting of the ‘Founding Council’ in Melbourne, chaired by General Peter The General Sir John Monash These2001 prestigious awardsGration enable AC OBEscholars (Retd) Foundation• The Federal provides Government postgraduate announces from a wide range of• Thedisciplines General to Sir deepen John Monash Foundation scholarships$5.1 million forto fund outstanding 32 Scholarships their expertise, achieveis incorporatedreal progress asin a public company limited for the first four years of the tackling some of the majorby guarantee challenges of our AustraliansFoundation to further their studies time and build invaluable global connections. anywhere in the world. 2002 • The Federal Government gifts Our Scholars all have the qualities of $250,000; Government of Victoria commitment to academic excellence, (State Electricity Commission) leadership and community• Inaugural service State embodied and Territory Selection Panels gifts $25,000 by General Sir John Monash.established around Australia 2003 • First 8 John Monash Scholarships awarded The Foundation is committed to growing for 2004 the Scholarship Endowment to $50 million The Federal Government grants by 2025, with the long-term goal of reaching $5 million to the Foundation’s $1002006 million to secure John Monash Endowment Fund Scholarships in perpetuity. -

David Whiting (Service No

EMU PARK SOLDIERS OF WORLD WAR I – THE GREAT WAR FROM EMU PARK and SHIRE OF LIVINGSTONE Private David Whiting (Service No. 361) of the 15th Infantry Battalion David was born on 29th September 1895 in Coowonga, Queensland, the second son of Herbert a farmer and Florence (née Whiteley) Whiting. Herbert arrived in Rockhampton in 1887 from England, and married Florence in 1892. Herbert worked on a farm at Coowonga in his early days, and during 1900 purchased and established apiaries at Emu Park and Coorooman. In 1902, he purchased a farm at Coowonga, known as Redding Farm and on the farm he ran his apiaries and grew fruit, vegetables, and corn. Around 1911, Herbert built a house and small shop at Emu Park and operated a mixed business from this shop. Early in David’s life, he worked on his parent’s farm until he left to work on a sheep station in western Queensland. After the First World War broke out in 1914, David had just turned 20 years of age and with his parents’ permission enlisted in the AIF on 17th October 1914. Private Whiting joined ‘B’ Company of the 15th Infantry Battalion, 4th Brigade which formed the Australian and New Zealand Division when they arrived in Egypt. (Note; this is the same company as Sergeant Robert Bull who is also commemorated at the Emu Park Centenary of ANZACs Memorial Gatehouse). In November, the Battalion left the Enoggera camp at Brisbane bound for Melbourne, arriving there on 26th November 1914. After further training, the Battalion boarded HMAT (A40) Ceramic at Port Melbourne and sailed for the Middle East on 22nd December 1914. -

OPERATIONS on NEW BRITAIN on the Island of New Britain in August

CHAPTER 1 0 OPERATIONS ON NEW BRITAIN N the island of New Britain in August 1944 there existed the sam e O kind of tacit truce as on Bougainville and the New Guinea mainland . In each area American garrisons guarded their air bases, the main Japanes e forces had been withdrawn to areas remote from the American ones, and , in the intervening no-man's land, Allied patrols, mostly of Australian-le d natives, waged a sporadic guerilla war against Japanese outposts an d patrols . In August 1944 one American regimental combat team was statione d in the Talasea-Cape Hoskins area on the north coast, one battalion group at Arawe on the south, and the remainder of the 40th Division, from whic h these groups were drawn, round Cape Gloucester at the western extremity . The main body of the Japanese army of New Britain—then believed t o be about 38,000 strong (actually about 93,000)—was concentrated i n the Gazelle Peninsula, but there were coastwatching stations farther west . In the middle area—about one-third of the island—field parties directe d by the Allied Intelligence Bureau were moving about, collecting informa- tion, helping the natives and winning their support, and harassing the enem y either by direct attack or by calling down air strikes . New Britain is some 320 miles in length and generally about 50 mile s in width, with a mountain spine rising steeply to 8,000 feet . On the south the coastal strip is generally narrow, but suitable landing places are fairl y frequent. -

4Th Army Facing on the Hindenburg Line, 6 October 1918

4th Army Facing on the Hindenburg Line 6 October 1918 IX Corps: Lieutenant General Sir W.P.Braithwaite 1st (British) Division: Major General E.P.Strickland 1st Brigade 1/Black Watch 1/Camron Highlanders 8/Royal Berkshire 1st Trench Mortar Battery 2nd Brigade 2/Royal Sussex 1/Northumberland 1/King's Royal Rifle Corps 2nd Trench Mortar Battery 3rd Brigade 1/South Wales Borderers 1/Gloucester 2/Welsh 2/Royal Munster Fusiliers 3rd Trench Mortar Battery XXV Artillery Brigade: 113th Battery 114th Battery 115th Battery D (H.) Battery XXXIX Artillery Brigade: 46th Battery 51st Battery 54th Battery 30 (H.) Battery Medium Trench Mortar Batteries: X.1 Y.1 Attached: 23rd, 26th, & 409th Engineer Field Companies 6/Welsh (Pioneers) No. 1 (Machinegun) Battalion, MGC Train: 1st Divisional Ammunition Column 1st Divisional Signals Company 1st, 2nd, & 141st Field Ambulances 2nd Mobile Veterinary Section 204th Divisional Employment Company 1st Divisional Train: 6th (British) Division: Major General T.O.Marden 16th Brigade: 1/Buffs 1/King's Shropshire Light Infantry 2/York and Lancaster Regiment 16th Trench Mortar Battery 17th Brigade: 1/West Yorkshire 1 2/Durham Light Infantry 11/Essex 17th Trench Mortar Battery 71st Brigade: 1/Leinster 2/Sherwood Foresters 9/Norfolk 71st Trench Mortar Battery II Artillery Brigade: 21st Battery 42nd Battery 53rd Battery 87th (H.) Battery XXIV Artillery Brigade: 110th Battery 111th Battery 112th Battery 43rd (H.) Battery Medium Trench Mortar Batteries: X.6 Y.6 Attached: 12th, 459th (West Riding) & 509th (London) Engineer Field -

Forgotten Anzacs Here Are Brief Biographies of the Five Perth Modern Soldiers Who Were Recently Added to the Plinth on the School’S War Memorial

Our forgotten ANZACs Here are brief biographies of the five Perth Modern soldiers who were recently added to the plinth on the school’s War Memorial. Arthur Bacon PMS student 1912 Edited from Forgotten Anzac – Arthur Bacon by Neil Coy with material from the ADFA website https://www.aif.adfa.edu.au/showPerson?pid=10014 Without any doubt the saddest omission from the School’s war memorial, and one of Perth Modern School’s most tragic personal stories of the Great War, is that of Arthur Bacon. Arthur Bacon was born on 24 September 1896. His family lived in a town site called Darling Range Quarries and his father operated a bluestone granite quarry at Gooseberry Hill. The School’s war memorial is built from granite from a nearby quarry. Arthur was educated initially at Midland Junction State School and then Guildford Grammar, where he passed the Senior Certificate. He enrolled in Perth Modern School on 7 February 1912. Arthur’s academic success at Modern School enabled him to study electrical engineering at UWA, at that time a fairly new and exciting field. Arthur enlisted in the Australian Imperial Forces on 7 June 1915 and was assigned to the 16th Battalion. The Battalion had suffered 70% casualties by the end of the first week at Gallipoli and Arthur was to be one of the reinforcements. He was given less than six weeks’ training before he arrived at Gallipoli during the last phase of preparation for the August, 1915 offensive. The 16th Battalion was set the most demanding of objectives, the capture of Hill 971, which was the highest point on Sari Bair Ridge. -

Shrine of Remembrance Plaque Map Pdf 1.15 MB

A09 A11 A13 A08 A09 A10 A14 Special Duties Squadrons Beaufort Squadrons 1, 2, 6, 7, 8, 13, 14, Sembawang Singapore 1, 8, 21, SECTION A South-West Pacific RAAF Odd Bods UK Association 86 Squadron RAAF RAAF United Kingdom 15, 32 and 100 and support units 453 & HQ Squadrons Ficus macrophylla (Moreton Bay Fig) Cupressus torulosa (Bhutan Cypress) 138 & 161 Cupressus torulosa (Bhutan Cypress) Lophostemon confertus (Brush Box) Cupressus torulosa (Bhutan Cypress) Corymbia maculata (Spotted Gum) Cupressus torulosa (Bhutan Cypress) A14 A18 A19 A19 B14 B17 B18 RAAF United Kingdom RAAF Malaya Australians in the Royal Air Force Royal Air Forces Association SECTION B 4 Division Signal Company Syria RAAF Mediterranean RAAF Lophostemon confertus (Brush Box) Angophora costata (Smooth-barked Apple Myrtle) Eucalyptus nicholii (Willow Lead Peppermint) Eucalyptus nicholii (Willow Lead Peppermint) Ulmus procera (English Elm) Corymbia citriodora (Lemon Scented Gum) Corymbia citriodora (Lemon Scented Gum) B19 B21 B22 B23 B24 B25 B29 B30 RAAF North Africa Nursing Service & WAAAF RAAF Western Europe RAAF 6 Field Ambulance RAAF South East Asia 57 Battalion Shrine Guard 39 Battalion Corymbia citriodora (Lemon Scented Gum) Corymbia citriodora (Lemon Scented Gum) Corymbia citriodora (Lemon Scented Gum) Corymbia citriodora (Lemon Scented Gum) Corymbia citriodora (Lemon Scented Gum) Corymbia maculata (Spotted Gum) Cupressus torulosa (Bhutan Cypress) Corymbia citriodora (Lemon Scented Gum) B33 B33 B34 B31 B32 B35 B36 B40 Australian and New New Zealand Army 3 Light Horse