Lessons in Leadership the Life of Sir John Monash GCMG, KCB, VD

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Major General James Harold CANNAN CB, CMG, DSO, VD

Major General James Harold CANNAN CB, CMG, DSO, VD [1882 – 1976] Major General Cannan is distinguished by his service in the Militia, as a senior officer in World War 1 and as the Australian Army’s Quartermaster General in World War 2. Major General James Harold Cannan, CB, CMG, DSO, VD (29 August 1882 – 23 May 1976) was a Queenslander by birth and a long-term member of the United Service Club. He rose to brigadier general in the Great War and served as the Australian Army’s Quartermaster General during the Second World War after which it was said that his contribution to the defence of Australia was immense; his responsibility for supply, transport and works, a giant-sized burden; his acknowledgement—nil. We thank the History Interest Group and other volunteers who have researched and prepared these Notes. The series will be progressively expanded and developed. They are intended as casual reading for the benefit of Members, who are encouraged to advise of any inaccuracies in the material. Please do not reproduce them or distribute them outside of the Club membership. File: HIG/Biographies/Cannan Page 1 Cannan was appointed Commanding Officer of the 15th Battalion in 1914 and landed with it at ANZAC Cove on the evening of 25 April 1915. The 15th Infantry Battalion later defended Quinn's Post, one of the most exposed parts of the Anzac perimeter, with Cannan as post commander. On the Western Front, Cannan was CO of 15th Battalion at the Battle of Pozières and Battle of Mouquet Farm. He later commanded 11th Brigade at the Battle of Messines and the Battle of Broodseinde in 1917, and the Battle of Hamel and during the Hundred Days Offensive in 1918. -

Responding to the Challenge

Responding Annual Report 2019/20 to the challenge Contents 01 About Us 02 Message from the Chairman 03 The Year in Review 04 202 John Monash Scholars 05 2020 Selection Analysis 06 2020 Scholarship Selection Process 07 2020 John Monash Scholars 12 Where Are They Now? 16 Impact 19 Publications and Awards 20 Events and Activities 23 John Monash Scholars’ Global Symposium 24 Governance 26 Foundation Members 27 Foundation Volunteers 28 Financial Highlights 30 Thank You 32 Partners and Supporters About Us Our mission is to invest in outstanding disciplines, possess a distinct General Sir John Australians from all fields of endeavour capacity for leadership Monash: the and are making significant who demonstrate remarkable qualities of contributions to Australia’s guiding spirit of leadership and have the ability to deliver future as scientists, academics, the Foundation outcomes and inspire others for the artists, business leaders, General Sir John Monash benefit of Australia. entrepreneurs, lawyers and was born in 1865 to Jewish policy experts. The General Sir John John Monash Scholars migrant parents from Prussia. Monash Foundation was General Sir John Monash said, He was educated at Scotch The General Sir John Monash established in 2001 with an ‘The privilege of education College in Melbourne and at Foundation supports initial contribution from the carries great responsibilities the University of Melbourne, exceptional scholars capable where he gained degrees in Australian Federal Government – it is given not for individual of identifying and tackling the Engineering, Law and Arts. together with further benefit alone, but to befit challenges of our time. We seek As a citizen soldier, he led contributions from corporate persons for the higher duties women and men of vision, the Australian Army Corps in supporters and private donors. -

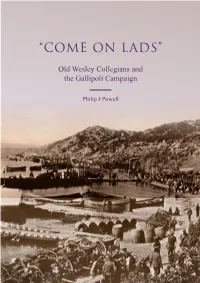

“Come on Lads”

“COME ON LADS” ON “COME “COME ON LADS” Old Wesley Collegians and the Gallipoli Campaign Philip J Powell Philip J Powell FOREWORD Congratulations, Philip Powell, for producing this short history. It brings to life the experiences of many Old Boys who died at Gallipoli and some who survived, only to be fatally wounded in the trenches or no-man’s land of the western front. Wesley annually honoured these names, even after the Second World War was over. The silence in Adamson Hall as name after name was read aloud, almost like a slow drum beat, is still in the mind, some seventy or more years later. The messages written by these young men, or about them, are evocative. Even the more humdrum and everyday letters capture, above the noise and tension, the courage. It is as if the soldiers, though dead, are alive. Geoffrey Blainey AC (OW1947) Front cover image: Anzac Cove - 1915 Australian War Memorial P10505.001 First published March 2015. This electronic edition updated February 2017. Copyright by Philip J Powell and Wesley College © ISBN: 978-0-646-93777-9 CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................. 2 Map of Gallipoli battlefields ........................................................ 4 The Real Anzacs .......................................................................... 5 Chapter 1. The Landing ............................................................... 6 Chapter 2. Helles and the Second Battle of Krithia ..................... 14 Chapter 3. Stalemate #1 .............................................................. -

Anzac Day 2015

RESEARCH PAPER SERIES, 2014-15 UPDATED 16 APRIL 2015 Anzac Day 2015 David Watt Foreign Affairs, Defence and Security Section This ‘Anzac Day Kit’ has been compiled over a number of years by various staff members of the Parliamentary Library, and is updated annually. In particular the Library would like to acknowledge the work of John Moremon and Laura Rayner, both of whom contributed significantly to the original text and structure of the Kit. Nathan Church and Stephen Fallon contributed to the 2015 edition of this publication. Contents Introduction ................................................................................................ 4 What is this kit? .................................................................................................. 4 Section 1: Speeches ..................................................................................... 4 Previous Anzac Day speeches ............................................................................. 4 90th anniversary of the Anzac landings—25 April 2005 .................................... 4 Tomb of the Unknown Soldier............................................................................ 5 Ataturk’s words of comfort ................................................................................ 5 Section 2: The relevance of Anzac ................................................................ 5 Anzac—legal protection ..................................................................................... 5 The history of Anzac Day ................................................................................... -

Structure of the New University. Begins to Emerge

Structure of the new university. ~~ begins to emerge ~ A CLEAR picture of the academic The 10 faculties of the enlarged Monash AMAGAZINE FORTHE UNIVERSITY structure of Monash University after I University will be Arts. Business, Com Registered by Australia Post - publication No. VBG0435 July 1990 has emerged from recent puting and Information Technology. NUMBER 7-89 DECEMBER 1, 1989 decisions of the councils of the univer Economics and Management. Education. sity. the Chisholm Institute of Engineering. Law. Medicine. Professional Studies. and Science. main the same, having no Chisholm but. to allow the college a measure of Technology and the Gippsland In In some of these a new academic group counterparts. autonomy and to maintain its regional stitute of Advanced Education. ing. known as a "school", will be in The new Faculty of Professional Studies flavor. it will retain a college chief ex. ecutive officer. council and academic After that date, the university - an troduced. It is defined as an academic unit will include a School of Social and board which will be responsible-to and ad amalgamation of the three institutions - within a faculty that may include a number Behavioral Studies comprising the vise their Monash counterparts. will consist of 10 faculties spread over ofdepartments. or other academic units. of Graduate School of Librarianship. the campuses in Caulfield, Clayton and similar or related disciplines. Monash department of Social Work, and The college council will have delegated the Chisholm departments of Police authority to allocate the operating budget, Frankston, together with a constituent The present faculty of Arts will gain approve staffing and set up advisory com university college in Gippsland which, the Chisholm department of Applied Studies. -

Kelson Nor Mckernan

Vol. 5 No. 9 November 1995 $5.00 Fighting Memories Jack Waterford on strife at the Memorial Ken Inglis on rival shrines Great Escapes: Rachel Griffiths in London, Chris McGillion in America and Juliette Hughes in Canberra and the bush Volume 5 Number 9 EURE:-KA SJRE:i:T November 1995 A magazine of public affairs, the arts and th eology CoNTENTS 4 30 COMMENT POETRY Seven Sketches by Maslyn Williams. 9 CAPITAL LETTER 32 BOOKS 10 Andrew Hamilton reviews three recent LETTERS books on Australian immigration; Keith Campbell considers The Oxford 12 Companion to Philosophy (p36); IN GOD WE BUST J.J.C. Smart examines The Moral Chris McGillion looks at the implosion Pwblem (p38); Juliette Hughes reviews of America from the inside. The Letters of Hildegard of Bingen Vol I and Hildegard of Bingen and 14 Gendered Theology in Ju dea-Christian END OF THE GEORGIAN ERA Tradition (p40); Michael McGirr talks Michael McGirr marks the passing of a to Hugh Lunn, (p42); Bruce Williams Melbourne institution. reviews A Companion to Theatre in Australia (p44); Max T eichrnann looks 15 at Albert Speer: His Battle With Truth COUNTERPOINT (p46); James Griffin reviews To Solitude The m edia's responsibility to society is Consigned: The Journal of William m easured by the code of ethics, says Smith O'BTien (p48). Paul Chadwick. 49 17 THEATRE ARCHIMEDES Geoffrey Milne takes a look at quick changes in W A. 18 WAR AT THE MEMORIAL 51 Ja ck Waterford exarnines the internal C lea r-fe Jl ed forest area. Ph oto FLASH IN THE PAN graph, above left, by Bill T homas ructions at the Australian War Memorial. -

The Final Campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year The final campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945 Karl James University of Wollongong James, Karl, The final campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945, PhD thesis, School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2005. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/467 This paper is posted at Research Online. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/467 The Final Campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Philosophy from University of Wollongong by Karl James, BA (Hons) School of History and Politics 2005 i CERTIFICATION I, Karl James, declare that this thesis, submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, is wholly my work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Karl James 20 July 2005 ii Table of Contents Maps, List of Illustrations iv Abbreviations vi Conversion viii Abstract ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1 ‘We have got to play our part in it’. Australia’s land war until 1944. 15 2 ‘History written is history preserved’. History’s treatment of the Final Campaigns. 30 3 ‘Once the soldier had gone to war he looked for leadership’. The men of the II Australian Corps. 51 4 ‘Away to the north of Queensland, On the tropic shores of hell, Stand grimfaced men who watch and wait, For a future none can tell’. The campaign takes shape: Torokina and the Outer Islands. -

Bull Brothers – Robert and Henry

EMU PARK SOLDIERS OF WORLD WAR I – THE GREAT WAR FROM EMU PARK and SHIRE OF LIVINGSTONE The Bull Brothers – Robert and Henry Sergeant Robert Charles Bull (Service No. 268) of the 15th Infantry Battalion and 1st Battalion Imperial Camel Brigade Robert was born on 17th May 1895 in a railway camp at Boolburra, the 9th child and 3rd son to Henry and Maria (née Ferguson) Bull, both immigrants from the United Kingdom. Henry from Whaplode, Lincolnshire, arrived in Rockhampton in 1879 at the age of 19. Maria was from Cookstown, Tyrone, North Ireland, arrived in Maryborough, also in 1879 and also aged 19. Robert spent his early years at Bajool before joining the Railway Service as a locomotive cleaner. He enlisted in the Australian Imperial Forces (AIF) on 16 September 1914 at Emerald where he gave his age as 21 years & 4 months, when in fact he was only 19 years & 4 months. Private Bull joined ‘B’ Company of the 15th Infantry Battalion, 4th Brigade which formed the Australian and New Zealand Division when they arrived in Egypt. The 15th Infantry Battalion consisted on average of 29 Officers and 1007 Other Ranks (OR’s) and was broken up into the following sub units: Section Platoon Company Battalion Rifle section:- Platoon Headquarters Company Battalion 10 OR’s (1 Officer & 4 OR’s) Headquarters (2 Headquarters (5 Officers & 57 Officers & 75 OR’s) Lewis Gun Section:- 10 3 Rifle Sections and OR’s) OR’s and 1 Lewis gun Section 4 Companies 1 Light Machine Gun 4 Platoons He sailed for Egypt aboard the HMAT (A40) Ceramic on 22nd December 1914. -

Your Presentation Is the Keynote Presentation for the Block

1984 RUSI VIC BLAMEY ORATION By Major General Ken G. Cooke, ED There must be something special about a man who on the centenary of his birth and thirty-three years after his death can still trigger a gathering of so many people, including so many busy and distinguished people, in a Melbourne park on a Tuesday morning in January. So let us take a few minutes to review briefly the life of Thomas Alfred Blamey to try and determine just how this can be. He was born on 24th January, 1884 on the outskirts of Wagga Wagga, the seventh of the ten children of Richard and Margaret Blamey. His father had tried his luck at farming, both in Queensland and New South Wales, but as was often the case the ventures ended in disaster due to the old traditional enemies of drought, bush fire and fluctuating cattle prices. He then settled in Wagga where he earned his living as a contract drover. His was a pioneer family so typical of the time and it exemplified the strength of our immigrant stock both before and since. Young Tom was educated in Wagga, first at the Government school and then for the last two years at the Grammar school to which he won a place on his pure ability. His upbringing generally was as you would expect. He had to help around the family property before and after school and on vacations he worked as a tar- boy in the local shearing sheds. As he grew older he went on several droving trips to help his father. -

CHAPTER JX Ll-Rr Rr2e the Left of the 3Rd .4Ustralian Division Was A\\Istiiig

CHAPTER JX MORLANCOURT-MARCH 28~~AND 30~11 ll-rrrr2E the left of the 3rd .4ustralian Division was a\\istiiig the 35th British Division to repel tlie attacks on 'I'reus. its right was watching rather perplesedly, from the folds aliove the Somme, scattered evidences of a hattle \\hich was apparently proceeding across tlie region southward f roni the rivet- At the saiiie time preparations were 111 progress for immediately mdertnking the projected advance of the division's line. Brigadier-General Cannan, who was visited during :he niorning by his divisional commander, General Motlash, obtained from him the impression that this advance \vas intended rather as a demonstration-to itnpress the Germans with the fact that their progress in that sector was at an end. Cannan accordingly put forward a plan, already prepared, for a patrol action. The 43rd, holding the higher part of the slope above the Soninie, would try to steal, by daylight patrols, the un- occupied portion of the knuckle in its front and possibly part of tlie nest spur, in front of Morlan- court. The ground so occupied would afterwards be consolidated Monash also visited General McNicoll, commanding his northern brigade. the xotli. and arranged for an advance on its front also. Tt was probably after these visits. 1)ut before noon, that Monash received from VI I Corps an important communication. It had been made known that the conference at Doullens had arrived at the decision--welcomed with intense satisfaction throughout the British Army-to give suprenie control over 212 z6th-28th Mar., 19181 MORLANCOURT 213 the Allies’ forces on the Western Front to a single leader- the French general, Foch. -

PDF Download Pozieres: the Anzac Story

POZIERES: THE ANZAC STORY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Scott Bennett | 416 pages | 01 Jan 2013 | Scribe Publications | 9781921844836 | English | Carlton North, Australia Pozieres: The Anzac Story : Scott Bennett : Howard predicts "a bloody holocaust". Elliott urges him to go back to Field Marshal Haig and inform him that Haking's strategy is flawed. Whether or not Howard was able to do so, remains unclear, but by the morning of the 19th the only result has been a delay in the operation. German defences on the Aubers Ridge and at Fromelles are substantial and continue to cause immense tactical difficulties for the British and Australians. By July , the 6th Bavarian Reserve Division holds more than 7 kilometres of the German front line. Each of the Division's regiments has been allocated a sector, each in turn manned by individual infantry companies. The trenches never run in a completely straight line, but are zig zagged to limit the damage from artillery, machine gun fire and bombing attacks. At their strongest, the German trenches are protected by sandbagged breastworks over two metres high and six metres deep, which makes them resistant to all but direct hits by artillery. This line is further protected by thick bands of barbed wire entanglements. There are two salients in the German line where the opposing forward trenches are at their closest. One is called the Sugarloaf and the other, Wick. Both are heavily fortified and from where machine gunners overlook no man's land and the Allied lines beyond. Along the German line, there are about 75 solid concrete shelters. -

Foxtel Programming in 2015 (PDF)

FOXTEL programming in 2015 GOGGLEBOX Season 1 The LifeStyle Channel Based on the U.K. smash hit, Gogglebox is a weekly observational series which captures the reactions of ordinary Australians as they watch the nightly news, argue over politics, cheer their favourite sporting teams and digest current affairs and documentaries. Twelve households will be chosen and then rigged with special, locked off cameras to capture every unpredictable moment. Gogglebox is like nothing else ever seen on Australian television and it’s set to hook audiences in a fun and entertaining way. The series has been commissioned jointly by Foxtel and Network Ten and will air first on The LifeStyle Channel followed by Channel Ten. DEADLINE GALLIPOLI Season 1 showcase Deadline Gallipoli explores the origin of the Gallipoli legend from the point of view of war correspondents Charles Bean, Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett, Phillip Schuler and Keith Murdoch, who lived through the campaign and bore witness to the extraordinary events that unfolded on the shores of Gallipoli in 1915. This compelling four hour miniseries captures the heartache and futility of war as seen through the eyes of the journalists who reported it. Joel Jackson stars as Bean, Hugh Dancy as Bartlett, Ewen Leslie as Murdoch, and Sam Worthington as Schuler. Charles Dance plays Hamilton, the Commander of the Gallipoli campaign, Bryan Brown plays General Bridges and John Bell plays Lord Kitchener. Deadline Gallipoli will be broadcast to coincide with the World War I Centenary commemorations. THE KETTERING INCIDENT Season 1 showcase Elizabeth Debicki, Matt Le Nevez, Anthony Phelan, Henry Nixon and Sacha Horler star in The Kettering Incident drama series.