Anzac Day 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commemorating the Overseas-Born Victoria Cross Heroes a First World War Centenary Event

Commemorating the overseas-born Victoria Cross heroes A First World War Centenary event National Memorial Arboretum 5 March 2015 Foreword Foreword The Prime Minister, David Cameron The First World War saw unprecedented sacrifice that changed – and claimed – the lives of millions of people. Even during the darkest of days, Britain was not alone. Our soldiers stood shoulder-to-shoulder with allies from around the Commonwealth and beyond. Today’s event marks the extraordinary sacrifices made by 145 soldiers from around the globe who received the Victoria Cross in recognition of their remarkable valour and devotion to duty fighting with the British forces. These soldiers came from every corner of the globe and all walks of life but were bound together by their courage and determination. The laying of these memorial stones at the National Memorial Arboretum will create a lasting, peaceful and moving monument to these men, who were united in their valiant fight for liberty and civilization. Their sacrifice shall never be forgotten. Foreword Foreword Communities Secretary, Eric Pickles The Centenary of the First World War allows us an opportunity to reflect on and remember a generation which sacrificed so much. Men and boys went off to war for Britain and in every town and village across our country cenotaphs are testimony to the heavy price that so many paid for the freedoms we enjoy today. And Britain did not stand alone, millions came forward to be counted and volunteered from countries around the globe, some of which now make up the Commonwealth. These men fought for a country and a society which spanned continents and places that in many ways could not have been more different. -

NEWSLETTER 2/2014 SEPTEMBER 2014 About but Had the Suitable Nightmares Associated with War the Duntroon Story and the and Death

NEWSLETTER 2/2014 SEPTEMBER 2014 about but had the suitable nightmares associated with war The Duntroon Story and the and death. Bridges Family A couple of years later my father was awarded the MBE, and remembering his comment that Bridges men only Peter Bridges survive one war with or without medals, I naively asked him if this was because he had been wounded in the war—in Charles Bean, in his 1957 work ‘Two Men I Knew’, WW2. He told me that the MBE medal was not for war time reflected that Major General Sir William Throsby Bridges achievements but for peace time achievements. As an eight- laid two foundations of Australia’s fighting forces in WWI— year old this seemed very odd that someone who worked Duntroon and the 1st Division. Many officers and soldiers in hard got medals. I still firmly believed you got medals for our Army have served in both these enduring institutions being enormously brave in war time. It didn’t make sense to and one might suspect, more than occasionally, reflected on me so I asked him why Bridges men died in war and he was Bridges significant legacy in each. still alive. The story then came out. I had the great pleasure to welcome Dr Peter Bridges to His grandfather, the General (WTB), had fought in the Duntroon in 2003 and from that visit, the College held for a Boer war in South Africa (against my mother’s grandfather decade, and to its Centenary, the medals of its Founder. The as it turns out) and had been wounded in the relief of willingness of Peter and the greater Bridges family to lend a Kimberley. -

Kelson Nor Mckernan

Vol. 5 No. 9 November 1995 $5.00 Fighting Memories Jack Waterford on strife at the Memorial Ken Inglis on rival shrines Great Escapes: Rachel Griffiths in London, Chris McGillion in America and Juliette Hughes in Canberra and the bush Volume 5 Number 9 EURE:-KA SJRE:i:T November 1995 A magazine of public affairs, the arts and th eology CoNTENTS 4 30 COMMENT POETRY Seven Sketches by Maslyn Williams. 9 CAPITAL LETTER 32 BOOKS 10 Andrew Hamilton reviews three recent LETTERS books on Australian immigration; Keith Campbell considers The Oxford 12 Companion to Philosophy (p36); IN GOD WE BUST J.J.C. Smart examines The Moral Chris McGillion looks at the implosion Pwblem (p38); Juliette Hughes reviews of America from the inside. The Letters of Hildegard of Bingen Vol I and Hildegard of Bingen and 14 Gendered Theology in Ju dea-Christian END OF THE GEORGIAN ERA Tradition (p40); Michael McGirr talks Michael McGirr marks the passing of a to Hugh Lunn, (p42); Bruce Williams Melbourne institution. reviews A Companion to Theatre in Australia (p44); Max T eichrnann looks 15 at Albert Speer: His Battle With Truth COUNTERPOINT (p46); James Griffin reviews To Solitude The m edia's responsibility to society is Consigned: The Journal of William m easured by the code of ethics, says Smith O'BTien (p48). Paul Chadwick. 49 17 THEATRE ARCHIMEDES Geoffrey Milne takes a look at quick changes in W A. 18 WAR AT THE MEMORIAL 51 Ja ck Waterford exarnines the internal C lea r-fe Jl ed forest area. Ph oto FLASH IN THE PAN graph, above left, by Bill T homas ructions at the Australian War Memorial. -

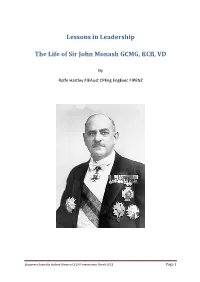

Lessons in Leadership the Life of Sir John Monash GCMG, KCB, VD

Lessons in Leadership The Life of Sir John Monash GCMG, KCB, VD By Rolfe Hartley FIEAust CPEng EngExec FIPENZ Engineers Australia Sydney Division CELM Presentation March 2013 Page 1 Introduction The man that I would like to talk about today was often referred to in his lifetime as ‘the greatest living Australian’. But today he is known to many Australians only as the man on the back of the $100 note. I am going to stick my neck out here and say that John Monash was arguably the greatest ever Australian. Engineer, lawyer, soldier and even pianist of concert standard, Monash was a true leader. As an engineer, he revolutionised construction in Australia by the introduction of reinforced concrete technology. He also revolutionised the generation of electricity. As a soldier, he is considered by many to have been the greatest commander of WWI, whose innovative tactics and careful planning shortened the war and saved thousands of lives. Monash was a complex man; a man from humble beginnings who overcame prejudice and opposition to achieve great things. In many ways, he was an outsider. He had failures, both in battle and in engineering, and he had weaknesses as a human being which almost put paid to his career. I believe that we can learn much about leadership by looking at John Monash and considering both the strengths and weaknesses that contributed to his greatness. Early Days John Monash was born in West Melbourne in 1865, the eldest of three children and only son of Louis and Bertha. His parents were Jews from Krotoshin in Prussia, an area that is in modern day Poland. -

The Great War Began at the End of July 1914 with the Triple Entente

ANZAC SURGEONS OF GALLIPOLI The Great War began at the end of July 1914 with the Triple Entente (Britain, France and Russia) aligned against the Triple Alliance (Germany, Austria- Hungary and Italy). By December, the Alliance powers had been joined by the Ottoman Turks; and in January 1915 the Russians, pressured by German and Turkish forces in the Caucasus, asked the British to open up another front. Hamilton second from right: There is nothing certain about war except that one side won’t win. AWM H10350 A naval campaign against Turkey was devised by the British The Turkish forces Secretary of State for War Lord Kitchener and the First Sea Lord, Winston Churchill. In 1913, Enver Pasha became Minister of War and de-facto Commander in Chief of the Turkish forces. He commanded It was intended that allied ships would destroy Turkish the Ottoman Army in 1914 when they were defeated by fortifications and open up the Straits of the Dardanelles, thus the Russians at the Battle of Sarikamiş and also forged the enabling the capture of Constantinople. alliance with Germany in 1914. In March 1915 he handed over control of the Ottoman 5th army to the German General Otto Liman von Sanders. It was intended that allied Von Sanders recognised the allies could not take Constantinople without a combined land and sea attack. ships would destroy Turkish In his account of the campaign, he commented on the small force of 60,000 men under his command but noted: The fortifications British gave me four weeks before their great landing. -

Bull Brothers – Robert and Henry

EMU PARK SOLDIERS OF WORLD WAR I – THE GREAT WAR FROM EMU PARK and SHIRE OF LIVINGSTONE The Bull Brothers – Robert and Henry Sergeant Robert Charles Bull (Service No. 268) of the 15th Infantry Battalion and 1st Battalion Imperial Camel Brigade Robert was born on 17th May 1895 in a railway camp at Boolburra, the 9th child and 3rd son to Henry and Maria (née Ferguson) Bull, both immigrants from the United Kingdom. Henry from Whaplode, Lincolnshire, arrived in Rockhampton in 1879 at the age of 19. Maria was from Cookstown, Tyrone, North Ireland, arrived in Maryborough, also in 1879 and also aged 19. Robert spent his early years at Bajool before joining the Railway Service as a locomotive cleaner. He enlisted in the Australian Imperial Forces (AIF) on 16 September 1914 at Emerald where he gave his age as 21 years & 4 months, when in fact he was only 19 years & 4 months. Private Bull joined ‘B’ Company of the 15th Infantry Battalion, 4th Brigade which formed the Australian and New Zealand Division when they arrived in Egypt. The 15th Infantry Battalion consisted on average of 29 Officers and 1007 Other Ranks (OR’s) and was broken up into the following sub units: Section Platoon Company Battalion Rifle section:- Platoon Headquarters Company Battalion 10 OR’s (1 Officer & 4 OR’s) Headquarters (2 Headquarters (5 Officers & 57 Officers & 75 OR’s) Lewis Gun Section:- 10 3 Rifle Sections and OR’s) OR’s and 1 Lewis gun Section 4 Companies 1 Light Machine Gun 4 Platoons He sailed for Egypt aboard the HMAT (A40) Ceramic on 22nd December 1914. -

Of Victoria Cross Recipients by New South Wales State Electorate

Index of Victoria Cross Recipients by New South Wales State Electorate INDEX OF VICTORIA CROSS RECIPIENTS BY NEW SOUTH WALES STATE ELECTORATE COMPILED BY YVONNE WILCOX NSW Parliamentary Research Service Index of Victoria Cross recipients by New South Wales electorate (includes recipients who were born in the electorate or resided in the electorate on date of enlistment) Ballina Patrick Joseph Bugden (WWI) resided on enlistment ............................................. 36 Balmain William Mathew Currey (WWI) resided on enlistment ............................................. 92 John Bernard Mackey (WWII) born ......................................................................... 3 Joseph Maxwell (WWII) born .................................................................................. 5 Barwon Alexander Henry Buckley (WWI) born, resided on enlistment ................................. 8 Arthur Charles Hall (WWI) resided on enlistment .................................................... 26 Reginald Roy Inwood (WWI) resided on enlistment ................................................ 33 Bathurst Blair Anderson Wark (WWI) born ............................................................................ 10 John Bernard Mackey (WWII) resided on enlistment .............................................. ..3 Cessnock Clarence Smith Jeffries (WWI) resided on enlistment ............................................. 95 Clarence Frank John Partridge (WWII) born........................................................................... 13 -

Foxtel Programming in 2015 (PDF)

FOXTEL programming in 2015 GOGGLEBOX Season 1 The LifeStyle Channel Based on the U.K. smash hit, Gogglebox is a weekly observational series which captures the reactions of ordinary Australians as they watch the nightly news, argue over politics, cheer their favourite sporting teams and digest current affairs and documentaries. Twelve households will be chosen and then rigged with special, locked off cameras to capture every unpredictable moment. Gogglebox is like nothing else ever seen on Australian television and it’s set to hook audiences in a fun and entertaining way. The series has been commissioned jointly by Foxtel and Network Ten and will air first on The LifeStyle Channel followed by Channel Ten. DEADLINE GALLIPOLI Season 1 showcase Deadline Gallipoli explores the origin of the Gallipoli legend from the point of view of war correspondents Charles Bean, Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett, Phillip Schuler and Keith Murdoch, who lived through the campaign and bore witness to the extraordinary events that unfolded on the shores of Gallipoli in 1915. This compelling four hour miniseries captures the heartache and futility of war as seen through the eyes of the journalists who reported it. Joel Jackson stars as Bean, Hugh Dancy as Bartlett, Ewen Leslie as Murdoch, and Sam Worthington as Schuler. Charles Dance plays Hamilton, the Commander of the Gallipoli campaign, Bryan Brown plays General Bridges and John Bell plays Lord Kitchener. Deadline Gallipoli will be broadcast to coincide with the World War I Centenary commemorations. THE KETTERING INCIDENT Season 1 showcase Elizabeth Debicki, Matt Le Nevez, Anthony Phelan, Henry Nixon and Sacha Horler star in The Kettering Incident drama series. -

'Feed the Troops on Victory': a Study of the Australian

‘FEED THE TROOPS ON VICTORY’: A STUDY OF THE AUSTRALIAN CORPS AND ITS OPERATIONS DURING AUGUST AND SEPTEMBER 1918. RICHARD MONTAGU STOBO Thesis prepared in requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities and Social Sciences University of New South Wales, Canberra June 2020 Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname/Family Name : Stobo Given Name/s : Richard Montagu Abbreviation for degree as given in the : PhD University calendar Faculty : History School : Humanities and Social Sciences ‘Feed the Troops on Victory’: A Study of the Australian Corps Thesis Title : and its Operations During August and September 1918. Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) This thesis examines reasons for the success of the Australian Corps in August and September 1918, its final two months in the line on the Western Front. For more than a century, the Corps’ achievements during that time have been used to reinforce a cherished belief in national military exceptionalism by highlighting the exploits and extraordinary fighting ability of the Australian infantrymen, and the modern progressive tactical approach of their native-born commander, Lieutenant-General Sir John Monash. This study re-evaluates the Corps’ performance by examining it at a more comprehensive and granular operational level than has hitherto been the case. What emerges is a complex picture of impressive battlefield success despite significant internal difficulties that stemmed from the particularly strenuous nature of the advance and a desperate shortage of manpower. These played out in chronic levels of exhaustion, absenteeism and ill-discipline within the ranks, and threatened to undermine the Corps’ combat capability. In order to reconcile this paradox, the thesis locates the Corps’ performance within the wider context of the British army and its operational organisation in 1918. -

Australia in the League of Nations: a Centenary View

RESEARCH PAPER SERIES, 2018–19 21 DECEMBER 2018 Australia in the League of Nations: a centenary view James Cotton Emeritus Professor of Politics, University of New South Wales, ADFA, Canberra Contents The League and global politics beyond the Empire-Commonwealth . 2 The requirements of membership ...................................................... 3 The Australian experience as a League mandatory ............................ 4 Peace, disarmament, collective security ............................................. 6 The League and the management of international trade and economic policy ................................................................................ 10 The League’s social agenda ............................................................... 11 Geneva as a school for international affairs for some prominent Australians ......................................................................................... 12 The Australian League of Nations Union........................................... 13 The League idea in Australia ............................................................. 14 Discussion of the League in the parliament and the debate on foreign affairs .................................................................................... 16 Conclusions: Australia in the League ................................................ 19 ISSN 2203-5249 The League and global politics beyond the Empire-Commonwealth With the formation of the Australian Commonwealth, the new nation adopted a constitution that imparted to the -

News Corporation 1 News Corporation

News Corporation 1 News Corporation News Corporation Type Public [1] [2] [3] [4] Traded as ASX: NWS ASX: NWSLV NASDAQ: NWS NASDAQ: NWSA Industry Media conglomerate [5] [6] Founded Adelaide, Australia (1979) Founder(s) Rupert Murdoch Headquarters 1211 Avenue of the Americas New York City, New York 10036 U.S Area served Worldwide Key people Rupert Murdoch (Chairman & CEO) Chase Carey (President & COO) Products Films, Television, Cable Programming, Satellite Television, Magazines, Newspapers, Books, Sporting Events, Websites [7] Revenue US$ 32.778 billion (2010) [7] Operating income US$ 3.703 billion (2010) [7] Net income US$ 2.539 billion (2010) [7] Total assets US$ 54.384 billion (2010) [7] Total equity US$ 25.113 billion (2010) [8] Employees 51,000 (2010) Subsidiaries List of acquisitions [9] Website www.newscorp.com News Corporation 2 News Corporation (NASDAQ: NWS [3], NASDAQ: NWSA [4], ASX: NWS [1], ASX: NWSLV [2]), often abbreviated to News Corp., is the world's third-largest media conglomerate (behind The Walt Disney Company and Time Warner) as of 2008, and the world's third largest in entertainment as of 2009.[10] [11] [12] [13] The company's Chairman & Chief Executive Officer is Rupert Murdoch. News Corporation is a publicly traded company listed on the NASDAQ, with secondary listings on the Australian Securities Exchange. Formerly incorporated in South Australia, the company was re-incorporated under Delaware General Corporation Law after a majority of shareholders approved the move on November 12, 2004. At present, News Corporation is headquartered at 1211 Avenue of the Americas (Sixth Ave.), in New York City, in the newer 1960s-1970s corridor of the Rockefeller Center complex. -

Page | 1 Keepsakes: Australians and the Great War 26 November 2014

Keepsakes: Australians and the Great War 26 November 2014 – 19 July 2015 EXHIBITION CHECKLIST INTRODUCTORY AREA Fred Davison (1869–1942) Scrapbook 1913–1942 gelatin silver prints, medals and felt; 36 x 52 cm (open) Manuscripts Collection, nla.cat-vn1179442 Eden Photo Studios Portrait of a young soldier seated in a carved chair c. 1915 albumen print on Paris Panel; 25 x 17.5 cm Pictures Collection, nla.pic-vn6419940 Freeman & Co. Portrait of Major Alexander Hay c. 1915 sepia toned gelatin silver print on studio mount; 33 x 23.5 cm Pictures Collection, nla.pic-an24213454 Tesla Studios Portrait of an Australian soldier c. 1915 gelatin silver print; 30 x 20 cm Pictures Collection, nla.pic-an24613311 The Sears Studio Group portrait of graduating students from the University of Melbourne c. 1918 gelatin silver print on studio mount; 25 x 30 cm Pictures Collection, nla.pic-an23218020 Portrait of Kenneth, Ernest, Clive and Alice Bailey c. 1918 sepia toned gelatin silver print on studio mount; 22.8 x 29.7 cm Pictures Collection, nla.pic-an23235834 Thelma Duryea Portrait of George Edwin Yates c. 1919 gelatin silver print on studio mount; 27.5 x 17.5 cm Pictures Collection, nla.pic-an10956957 Portrait of Gordon Coghill c. 1918 sepia toned gelatin silver print; 24.5 x 16 cm Pictures Collection, nla.pic-vn3638073 Page | 1 Australian soldiers in Egypt sitting on one of the corners of the base of the Great Pyramid of Cheops, World War 1, 1914–1918 c. 1916 sepia toned gelatin silver print on card mount; 12 x 10.5 cm Pictures Collection, nla.pic-an24613179 Embroidered postcard featuring a crucifix 1916 silk on card; 14 x 9 cm Papers of Arthur Wesley Wheen, nla.ms-ms3656 James C.