Miscellanea 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Didactic Fragmentation in ''Scenes from the Big Picture'

Didactic Fragmentation in ”Scenes from the Big Picture” (2003) by Owen McCafferty Virginie Privas-Bréauté To cite this version: Virginie Privas-Bréauté. Didactic Fragmentation in ”Scenes from the Big Picture” (2003) by Owen McCafferty. 2012. halshs-01071477 HAL Id: halshs-01071477 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01071477 Preprint submitted on 5 Oct 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. !1 Didactic Fragmentation in Scenes from the Big Picture (2003) by Owen McCafferty Virginie Privas-Bréauté Université Jean Moulin - Lyon 3 Brecht’s dramatic theory helps demonstrate that the contours of contemporary Northern Irish drama have been reshaped. In this respect, Owen McCafferty’s play Scenes from the Big Picture has Neo-Brechtian resonances. The audience is presented with frag- ments of lives of people, bits and pieces of a whole picture. This play exemplifies Brecht’s idea of a didactic play in so far as the audience is called to learn about the Northern Irish Troubles from the play through the device of fragmentation: the uneven background of McCafferty’s play – i.e. the Troubles – is peopled with traumatised indi- viduals, proportionally fragmented. -

The Theatre of the Real Yeats, Beckett, and Sondheim

The Theatre of the Real MMackenzie_final4print.indbackenzie_final4print.indb i 99/16/2008/16/2008 55:40:32:40:32 PPMM MMackenzie_final4print.indbackenzie_final4print.indb iiii 99/16/2008/16/2008 55:40:50:40:50 PPMM The Theatre of the Real Yeats, Beckett, and Sondheim G INA MASUCCI MACK ENZIE THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS • COLUMBUS MMackenzie_final4print.indbackenzie_final4print.indb iiiiii 99/16/2008/16/2008 55:40:50:40:50 PPMM Copyright © 2008 by Th e Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data MacKenzie, Gina Masucci. Th e theatre of the real : Yeats, Beckett, and Sondheim / Gina Masucci MacKenzie. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978–0–8142–1096–3 (cloth : alk. paper)—ISBN 978–0–8142–9176–4 (cd-rom) 1. English drama—Irish authors—History and criticism—Th eory, etc. 2. Yeats, W. B. (William Butler), 1865–1939—Dramatic works. 3. Beckett, Samuel, 1906–1989—Dramatic works. 4. Sondheim, Stephen—Criticism and interpretation. 5. Th eater—United States—History— 20th century. 6. Th eater—Great Britain—History—20th century. 7. Ireland—Intellectual life—20th century. 8. United States—Intellectual life—20th century. I. Title. PR8789.M35 2008 822.009—dc22 2008024450 Th is book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978–0–8142–1096–3) CD-ROM (ISBN 978–0–8142–9176–4) Cover design by Jason Moore. Text design by Jennifer Forsythe. Typeset in Adobe Minion Pro. Printed by Th omson-Shore, Inc. Th e paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. -

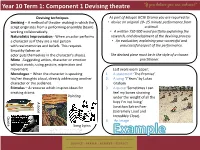

Year 10 Term 1: Component 1 Devising Theatre

Year 10 Term 1: Component 1 Devising theatre Devising techniques As part of Eduqas GCSE Drama you are required to: Devising – A method of theatre- making in which the • devise an original 10- 15 minute performance from script originates from a performing ensemble (team) a stimuli working collaboratively. • A written 750-900 word portfolio explaining the Naturalistic Improvisation - When an actor performs research, and development of the devising process. a character as if they are a real person • An evaluation, explaining your successful and with real memories and beliefs. This requires unsuccessful aspect of the performance. Empathy (when an actor puts themselves in the character’s shoes). The devised piece must be in the style of a chosen Mime -Suggesting action, character or emotion practitioner. without words, using gesture, expression and movement. Last years exam paper: Monologue – When the character is speaking 1. A statement ‘The Promise’ his/her thoughts aloud, directly addressing another 2. A song ‘7 Years’ by Lukas character or the audience. Graham Stimulus – A recourse which inspires ideas for 3. A quote ‘Sometimes I can creating drama. feel my bones straining Painting under the weight of all the A book lives I’m not living’ Jonathan Safran Foer (Extremely Loud and Quote Incredibly Close). 4. An Image Song Lyrics Year 10 Term 1: Component 1 Devising Theatre Research- Explore each stimuli, finding out all the A sequence in a chronological order fact around it. including a beginning, middle and end. Map ideas – Write all your initial ideas on a mind map. Discuss – Share your ideas with your group and decide on a final idea. -

Bollettini Novità Ottobre-Dicembre 2020

BOLLETTINO DI INFORMAZIONE SULLA STAMPA PERIODICA . INDICE PERIODICI . *Acque sotterranee : ricerca, trivellazione, captazione : organo ufficiale dell'A.N.I.P.A. *Alpi Giulie : rivista bimestrale della Società alpina delle Giulie . *Atti della Accademia ligure di scienze e lettere . *Atti della Accademia roveretana degli Agiati. Classe di scienze matematiche, fisiche e naturali . *Bollettino della Società geografica italiana . *Geologia dell'ambiente . *Gortania. Botanica, zoologia . *Gortania. Geologia, paleontologia, paletnologia . The *Italian Journal of Geosciences . *Rivista italiana di paleontologia e stratigrafia . *Mostrare gli italiani. La narrazione delle identità e delle migrazioni in due eventi espoitivi / Francesco Federici. - pp. 345-364 . *Eulerian-Lagrangian tracer simulation with THOUGH2 / Adrian E. Croucher ... [et al.] . *qUATTRO GATTI *Acque sotterranee : ricerca, trivellazione, captazione : organo ufficiale dell'A.N.I.P.A. / Associazione nazionale imprese pozzi acqua [poi: di idrogeologia e pozzi d'acqua]. - Vol. 1 (1984)-. - Segrate : Geo-Graph, [1984]-. - v. : ill. ; 30 cm. ((Bimestrale, poi trimestrale. - Il sottotitolo varia. - L'editore cambia: Piacenza : Acque sotterranee PER.IT.3 . Argentieri, Alessio <geologo> *Francesco Penta, a 1899 boy / Alessio Argentieri. - pp. 67-69 : ill. A.(2017), v. 6, n° 3/149, p. 67-69 . Dal_Piaz, Giorgio Vittorio - Argentieri, Alessio <geologo> *Sessant'anni del Traforo del Monte Bianco, la storia di un'impresa. Prologo: da Annibale alle grandi gallerie alpine / Giorgio Vittorio Dal Piaz, Alessio Argentieri. - pp. 75-81 : ill. A.(2019), v. 8 n°3/157, pp. 75-81 *Acque sotterranee : ricerca, trivellazione, captazione : organo ufficiale dell'A.N.I.P.A. / Associazione nazionale imprese pozzi acqua [poi: di idrogeologia e pozzi d'acqua]. - Vol. 1 (1984)-. - Segrate : Geo-Graph, [1984]-. -

Contemporary Art Magazine Issue # Sixteen December | January Twothousandnine Spedizione in A.P

contemporary art magazine issue # sixteen december | january twothousandnine Spedizione in a.p. -70% _ DCB Milano NOVEMBER TO JANUARY, 2009 KAREN KILIMNIK NOVEMBER TO JANUARY, 2009 WadeGUYTON BLURRY CatherineSULLIVAN in collaboration with Sean Griffin, Dylan Skybrook and Kunle Afolayan Triangle of Need VibekeTANDBERG The hamburger turns in my stomach and I throw up on you. RENOIR Liquid hamburger. Then I hit you. After that we are both out of words. January - February 2009 DEBUSSY URS FISCHER GALERIE EVA PRESENHUBER WWW.PRESENHUBER.COM TEL: +41 (0) 43 444 70 50 / FAX: +41 (0) 43 444 70 60 LIMMATSTRASSE 270, P.O.BOX 1517, CH–8031 ZURICH GALLERY HOURS: TUE-FR 12-6, SA 11-5 DOUG AITKEN, EMMANUELLE ANTILLE, MONIKA BAER, MARTIN BOYCE, ANGELA BULLOCH, VALENTIN CARRON, VERNE DAWSON, TRISHA DONNELLY, MARIA EICHHORN, URS FISCHER, PETER FISCHLI/DAVID WEISS, SYLVIE FLEURY, LIAM GILLICK, DOUGLAS GORDON, MARK HANDFORTH, CANDIDA HÖFER, KAREN KILIMNIK, ANDREW LORD, HUGO MARKL, RICHARD PRINCE, GERWALD ROCKENSCHAUB, TIM ROLLINS AND K.O.S., UGO RONDINONE, DIETER ROTH, EVA ROTHSCHILD, JEAN-FRÉDÉRIC SCHNYDER, STEVEN SHEARER, JOSH SMITH, BEAT STREULI, FRANZ WEST, SUE WILLIAMS DOUBLESTANDARDS.NET 1012_MOUSSE_AD_Dec2008.indd 1 28.11.2008 16:55:12 Uhr Galleria Emi Fontana MICHAEL SMITH Viale Bligny 42 20136 Milano Opening 17 January 2009 T. +39 0258322237 18 January - 28 February F. +39 0258306855 [email protected] www.galleriaemifontana.com Photo General Idea, 1981 David Lamelas, The Violent Tapes of 1975, 1975 - courtesy: Galerie Kienzie & GmpH, Berlin L’allarme è generale. Iper e sovraproduzione, scialo e vacche grasse si sono tra- sformati di colpo in inflazione, deflazione e stagflazione. -

Misc Thesisdb Bythesissuperv

Honors Theses 2006 to August 2020 These records are for reference only and should not be used for an official record or count by major or thesis advisor. Contact the Honors office for official records. Honors Year of Student Student's Honors Major Thesis Title (with link to Digital Commons where available) Thesis Supervisor Thesis Supervisor's Department Graduation Accounting for Intangible Assets: Analysis of Policy Changes and Current Matthew Cesca 2010 Accounting Biggs,Stanley Accounting Reporting Breaking the Barrier- An Examination into the Current State of Professional Rebecca Curtis 2014 Accounting Biggs,Stanley Accounting Skepticism Implementation of IFRS Worldwide: Lessons Learned and Strategies for Helen Gunn 2011 Accounting Biggs,Stanley Accounting Success Jonathan Lukianuk 2012 Accounting The Impact of Disallowing the LIFO Inventory Method Biggs,Stanley Accounting Charles Price 2019 Accounting The Impact of Blockchain Technology on the Audit Process Brown,Stephen Accounting Rebecca Harms 2013 Accounting An Examination of Rollforward Differences in Tax Reserves Dunbar,Amy Accounting An Examination of Microsoft and Hewlett Packard Tax Avoidance Strategies Anne Jensen 2013 Accounting Dunbar,Amy Accounting and Related Financial Statement Disclosures Measuring Tax Aggressiveness after FIN 48: The Effect of Multinational Status, Audrey Manning 2012 Accounting Dunbar,Amy Accounting Multinational Size, and Disclosures Chelsey Nalaboff 2015 Accounting Tax Inversions: Comparing Corporate Characteristics of Inverted Firms Dunbar,Amy Accounting Jeffrey Peterson 2018 Accounting The Tax Implications of Owning a Professional Sports Franchise Dunbar,Amy Accounting Brittany Rogan 2015 Accounting A Creative Fix: The Persistent Inversion Problem Dunbar,Amy Accounting Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act: The Most Revolutionary Piece of Tax Szwakob Alexander 2015D Accounting Dunbar,Amy Accounting Legislation Since the Introduction of the Income Tax Prasant Venimadhavan 2011 Accounting A Proposal Against Book-Tax Conformity in the U.S. -

Extended Sensibilities Homosexual Presence in Contemporary Art

CHARLEY BROWN SCOTT BURTON CRAIG CARVER ARCH CONNELLY JANET COOLING BETSY DAMON NANCY FRIED EXTENDED SENSIBILITIES HOMOSEXUAL PRESENCE IN CONTEMPORARY ART JEDD GARET GILBERT & GEORGE LEE GORDON HARMONY HAMMOND JOHN HENNINGER JERRY JANOSCO LILI LAKICH LES PETITES BONBONS ROSS PAXTON JODY PINTO CARLA TARDI THE NEW MUSEUM FRAN WINANT EXTENDED SENSIBILITIES HOMOSEXUAL PRESENCE IN CONTEMPORARY ART CHARLEY BROWN HARMONY HAMMOND SCOTT BURTON JOHN HENNINGER CRAIG CARVER JERRY JANOSCO ARCH CONNELLY LILI LAKICH JANET COOLING LES PETITES BONBONS BETSY DAMON ROSS PAXTON NANCY FRIED JODY PINTO JEDD GARET CARLA TARDI GILBERT & GEORGE FRAN WINANT LE.E GORDON Daniel J. Cameron Guest Curator The New Museum EXTENDED SENSIBILITIES STAFF ACTIVITIES COUNCJT . Robin Dodds Isabel Berley HOMOSEXUAL PRESENCE IN CONTEMPORARY ART Nina Garfinkel Marilyn Butler N Lynn Gumpert Arlene Doft ::;·z17 John Jacobs Elliot Leonard October 16-December 30, 1982 Bonnie Johnson Lola Goldring .H6 Ed Jones Nanette Laitman C:35 Dieter Morris Kearse Dorothy Sahn Maria Reidelbach Laura Skoler Rosemary Ricchio Jock Truman Ned Rifkin Charles A. Schwefel INTERNS Maureen Stewart Konrad Kaletsch Marcia Thcker Thorn Middlebrook GALLERY ATTENDANTS VOLUNTEERS Joanne Brockley Connie Bangs Anne Glusker Bill Black Marcia Landsman Carl Blumberg Sam Robinson Jeanne Breitbart Jennifer Q. Smith Mary Campbell Melissa Wolf Marvin Coats Jody Cremin This exhibition is supported by a grant from the National Endowment for BOARD OF TRUSTEES Joanna Dawe the Arts in Washington, D.C., a Federal Agency, and is made possible in Jack Boulton Mensa Dente part by public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts. Elaine Dannheisser Gary Gale Library of Congress Catalog Number: 82-61279 John Fitting, Jr. -

Di Riccardo Chieppa**

PERSECUZIONI RAZZIALI (1938-1945), EPISODI DI DISCORDANZE E CASI DI SPECULAZIONE: TRA GENEROSI CORAGGIOSI E MESCHINI PROFITTATORI* di Riccardo Chieppa** SOMMARIO: 1. Il perché della presente ricerca. – 2. Premessa sul movimento e regime fascista, le comunità di ebrei italiani e l’atteggiamento della collettività. – 3. Il primo periodo (1938 – entrata in guerra – 8 settembre 1943): tra iniziale indifferenza e progressivi episodi di discordanza. – 3.1. Reazioni nella scuola. – 3.2. Periodo bellico fino al settembre 1943. – 4. Il secondo periodo: c.d. R.S.I., il tedesco invasore: resistenza civile e generosità diffusa. – 5. Profili economici delle operazioni antirazziali e meschini profittatori: spoliazioni, una continuità crescente nei due periodi. 1. Il perché della presente ricerca 1 * Costituisce l’ampliamento e il completamento con notevoli integrazioni, e aggiunte, nell’ambito di una più vasta ricerca, del mio contributo Persecuzioni razziali(1938-1945) episodi di speculazione e meschini profittatori, pubblicato in Razza e ingiustizia, Gli avvocati e i magistrati al tempo delle leggi antiebraiche, a Cura di A. MENICONI e M. PEZZETTI, Roma, 2018, su iniziativa congiunta del Consiglio Superiore della Magistratura, Consiglio Nazionale Forense, Senato della Repubblica e Unione delle Comunità Ebraiche Italiane, presentato il 14 settembre 2018, a Palazzo Madama. ** Presidente emerito della Corte costituzionale 1 Bibliografia generale, oltre le indicazioni nel testo e altre note particolari: G. ACERBI, Le leggi antiebraiche e razziali italiane e il ceto dei giuristi, Milano 2011; C. BRUSCO, Le leggi razziali, i magistrati, i giuristi, le riviste giuridiche, magistratura democratica, 2018; P. CALAMANDREI, Diario 1939-1945 (a cura di G. AGOSTI), Firenze 197I; G. -

Appendix: Biographies of Jesuit Righteous Among the Nations

journal of jesuit studies 5 (2018) 256-265 brill.com/jjs Appendix: Biographies of Jesuit Righteous among the Nations We are pleased to present here the biographies of the fifteen Jesuits who have been identified and honored by Yad Vashem with the title “Righteous among the Nations.” For permission to include these in this issue, we wish to thank the staff of Yad Vashem, especially Ms. Irena Steinfeldt and the editors of The Encyclopedia of the Righteous among the Nations (www.yadvashem.org). Boetto, Father Pietro Jesuit Cardinal Pietro Boetto (1871–1946) was the archbishop of Genoa from 1938 to 1946 after many years in leadership positions in the Society of Jesus. Pope Pius xi named him a cardinal in 1935. He has been recognized for saving many Jewish lives while working with the outlawed Jewish rescue network “Delasem.” He and his secretary Fr. Francesco Repetto “recruited bishops and archbishops throughout northern Italy to help in this endeavor, thus creating rescue networks that saved hundreds, if not thousands, of Jews […]. The help included shelter in religious institutions, false documents, hospitalization un- der false names, and escape to Switzerland.” On November 14, 2016, Yad Vashem honored Cardinal Pietro Boetto as Righ- teous among the Nations. Braun, Father Roger Roger Braun was a Jesuit priest. During the war, he devoted himself to the sav- ing of persecuted Jews without any attempt to proselytize them. On the con- trary, he tried to persuade Jews to adhere to their ancestral faith. After the war, Rabbi Henri Schilli, who became the director of the rabbinical seminary in Paris in 1950, related how father Braun’s principle of solidarity with the Jews dominated the priest’s actions during the entire occupation. -

Nationalism, Primitivism, & Neoclassicism

Nationalism, Primitivism, & Neoclassicism" Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971)! Biographical sketch:! §" Born in St. Petersburg, Russia.! §" Studied composition with “Mighty Russian Five” composer Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov.! §" Emigrated to Switzerland (1910) and France (1920) before settling in the United States during WW II (1939). ! §" Along with Arnold Schönberg, generally considered the most important composer of the first half or the 20th century.! §" Works generally divided into three style periods:! •" “Russian” Period (c.1907-1918), including “primitivist” works! •" Neoclassical Period (c.1922-1952)! •" Serialist Period (c.1952-1971)! §" Died in New York City in 1971.! Pablo Picasso: Portrait of Igor Stravinsky (1920)! Ballets Russes" History:! §" Founded in 1909 by impresario Serge Diaghilev.! §" The original company was active until Diaghilev’s death in 1929.! §" In addition to choreographing works by established composers (Tschaikowsky, Rimsky- Korsakov, Borodin, Schumann), commissioned important new works by Debussy, Satie, Ravel, Prokofiev, Poulenc, and Stravinsky.! §" Stravinsky composed three of his most famous and important works for the Ballets Russes: L’Oiseau de Feu (Firebird, 1910), Petrouchka (1911), and Le Sacre du Printemps (The Rite of Spring, 1913).! §" Flamboyant dancer/choreographer Vaclav Nijinsky was an important collaborator during the early years of the troupe.! ! Serge Diaghilev (1872-1929) ! Ballets Russes" Serge Diaghilev and Igor Stravinsky.! Stravinsky with Vaclav Nijinsky as Petrouchka (Paris, 1911).! Ballets -

Introduction

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. INTRODUCTION “We were taught as children”—I was told by a seventy- year-old Pole—“that we Poles never harmed anyone. A partial abandonment of this morally comfortable position is very, very difficult for me.” —Helga Hirsch, a German journalist, in Polityka, 24 February 2001 HE COMPLEX and often acrimonious debate about the charac- ter and significance of the massacre of the Jewish population of T the small Polish town of Jedwabne in the summer of 1941—a debate provoked by the publication of Jan Gross’s Sa˛siedzi: Historia za- głady z˙ydowskiego miasteczka (Sejny, 2000) and its English translation Neighbors: The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne, Poland (Princeton, 2001)—is part of a much wider argument about the totali- tarian experience of Europe in the twentieth century. This controversy reflects the growing preoccupation with the issue of collective memory, which Henri Rousso has characterized as a central “value” reflecting the spirit of our time.1 One key element in the understanding of collec- tive memory is the “dark past” of nations—those aspects of the na- tional past that provoke shame, guilt, and regret; this past needs to be integrated into the national collective identity, which itself is continu- ally being reformulated.2 In this sense, memory has to be understood as a public discourse that helps to build group identity and is inevita- bly entangled in a relationship of mutual dependence with other iden- tity-building processes. -

HANAN 2 Chedet.Co.Cc February 19, 2009 by Dr. Mahathir Mohamad

HANAN 2 Chedet.co.cc February 19, 2009 By Dr. Mahathir Mohamad Dear Hanan, 1. I think I cannot convince you on anything simply because your perception of things is not based on logic or reason but merely on your strong belief that you are always right, even if the whole world says you are wrong. 2. Jews have lived with Muslims in Muslim countries for centuries without any serious problem. 3. On the other hand in Europe, Jews were persecuted. Every now and again there would be pogroms when the Europeans would massacre Jews. The Holocaust did not happen in Muslim countries. Muslims may discriminate against Jews but did not massacre them. 4. But now you are fighting the largely Muslim Palestinians. It cannot be because of religious differences or the killing of Jews living among them. It must be because you have taken their land and expelled them from their homeland. It is therefore not a religious war. But of course as you seek sympathisers from among the non-Muslims, the Palestinians seek sympathisers among the Muslims. That still does not make the war a religious war. 5. Whether you speak Hebrew or not is not relevant. Lots of people who are not English speak English. They don't belong to England. For centuries you could speak Hebrew but remained Germans, British, French, Russians etc. 6. Lots of Jews cannot speak Hebrew but they are still Jews. Merely being able to speak Hebrew does not entitle you to claim Palestine. 7. The Jews had lived in Europe for centuries.