The Theatre of the Real Yeats, Beckett, and Sondheim

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Didactic Fragmentation in ''Scenes from the Big Picture'

Didactic Fragmentation in ”Scenes from the Big Picture” (2003) by Owen McCafferty Virginie Privas-Bréauté To cite this version: Virginie Privas-Bréauté. Didactic Fragmentation in ”Scenes from the Big Picture” (2003) by Owen McCafferty. 2012. halshs-01071477 HAL Id: halshs-01071477 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01071477 Preprint submitted on 5 Oct 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. !1 Didactic Fragmentation in Scenes from the Big Picture (2003) by Owen McCafferty Virginie Privas-Bréauté Université Jean Moulin - Lyon 3 Brecht’s dramatic theory helps demonstrate that the contours of contemporary Northern Irish drama have been reshaped. In this respect, Owen McCafferty’s play Scenes from the Big Picture has Neo-Brechtian resonances. The audience is presented with frag- ments of lives of people, bits and pieces of a whole picture. This play exemplifies Brecht’s idea of a didactic play in so far as the audience is called to learn about the Northern Irish Troubles from the play through the device of fragmentation: the uneven background of McCafferty’s play – i.e. the Troubles – is peopled with traumatised indi- viduals, proportionally fragmented. -

Stage Violence, Power and the Director an Examination

STAGE VIOLENCE, POWER AND THE DIRECTOR AN EXAMINATION OF THE THEORY AND PRACTICE OF CRUELTY FROM ANTONIN ARTAUD TO SARAH KANE by Jordan Matthew Walsh Bachelor of Philosophy, University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Pittsburgh in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Philosophy. The University of Pittsburgh May 2012 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH ARTS & SCIENCES This thesis was presented by Jordan Matthew Walsh It was defended on April 13th, 2012 and approved by Jesse Berger, Artistic Director, Red Bull Theater Company Cynthia Croot, Assistant Professor, Theatre Arts Department Annmarie Duggan, Assistant Professor, Theatre Arts Department Dr. Lisa Jackson-Schebetta, Assistant Professor, Theatre Arts Department 2 Copyright © by Jordan Matthew Walsh 2012 3 STAGE VIOLENCE AND POWER: AN EXAMINATION OF THE THEORY AND PRACTICE OF CRUELTY FROM ANTONIN ARTAUD TO SARAH KANE Jordan Matthew Walsh, BPhil University of Pittsburgh, 2012 This exploration of stage violence is aimed at grappling with the moral, theoretical and practical difficulties of staging acts of extreme violence on stage and, consequently, with the impact that these representations have on actors and audience. My hypothesis is as follows: an act of violence enacted on stage and viewed by an audience can act as a catalyst for the coming together of that audience in defense of humanity, a togetherness in the act of defying the truth mimicked by the theatrical violence represented on stage, which has the potential to stir the latent power of the theatre communion. I have used the theoretical work of Antonin Artaud, especially his “Theatre of Cruelty,” and the works of Peter Brook, Jerzy Grotowski, and Sarah Kane in conversation with Artaud’s theories as a prism through which to investigate my hypothesis. -

Autori / Contributors

Studi irlandesi. A Journal of Irish Studies, n. 2 (2012), pp. 505-510 http://www.fupress.com/bsfm-sijis Autori / Contributors Arianna Antonielli (<[email protected]>) earned her PhD in English and American Studies at the University of Florence. She is currently edi- tor in chief of the Open Access Publishing Workshop (Dept. Comparative Languages, Literatures and Cultures), journal manager of the OA journals «LEA», «Studi irlandesi. A Journal of Irish Studies», and «Journal of Early Modern Studies», as well as editorial secretary of the OA series “Biblioteca di Studi di Filologia Moderna” and web master of their websites. She is the author of William Blake e William Butler Yeats. Sistemi simbolici e costruzioni poetiche (2009) and W.B. Yeats’s and J.E. Ellis’s manuscript version of The Works of William Blake: Poetic, Symbolic and Critical. A Manuscript Edition with Critical Analysis (forthcoming 2013). She has written essays on T.S. Eliot, W. Blake, W.B. Yeats, A. Gyles, A. France, and C.A. Smith. Davide Barbuscia (<[email protected]>) holds a PhD in Anglo- American Studies. Among his interests: the 18th century English novel, Mikhail Bakhtin, Samuel Beckett, Don DeLillo, post-modern theory, the philosophy of time, the relationship between cinema and literature. His PhD dissertation on DeLillo and Beckett was awarded the Firenze University Press Prize 2012 and is due to be published in 2013. Matteo Binasco (<[email protected]>) is research fellow at the Institute of History of Mediterranean Europe of Italy’s National Research Council (CNR). He is the author of Viaggiatori e missionari nel Seicento (2006), editor of Little Do We Know. -

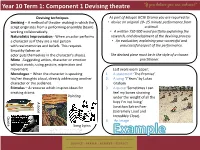

Year 10 Term 1: Component 1 Devising Theatre

Year 10 Term 1: Component 1 Devising theatre Devising techniques As part of Eduqas GCSE Drama you are required to: Devising – A method of theatre- making in which the • devise an original 10- 15 minute performance from script originates from a performing ensemble (team) a stimuli working collaboratively. • A written 750-900 word portfolio explaining the Naturalistic Improvisation - When an actor performs research, and development of the devising process. a character as if they are a real person • An evaluation, explaining your successful and with real memories and beliefs. This requires unsuccessful aspect of the performance. Empathy (when an actor puts themselves in the character’s shoes). The devised piece must be in the style of a chosen Mime -Suggesting action, character or emotion practitioner. without words, using gesture, expression and movement. Last years exam paper: Monologue – When the character is speaking 1. A statement ‘The Promise’ his/her thoughts aloud, directly addressing another 2. A song ‘7 Years’ by Lukas character or the audience. Graham Stimulus – A recourse which inspires ideas for 3. A quote ‘Sometimes I can creating drama. feel my bones straining Painting under the weight of all the A book lives I’m not living’ Jonathan Safran Foer (Extremely Loud and Quote Incredibly Close). 4. An Image Song Lyrics Year 10 Term 1: Component 1 Devising Theatre Research- Explore each stimuli, finding out all the A sequence in a chronological order fact around it. including a beginning, middle and end. Map ideas – Write all your initial ideas on a mind map. Discuss – Share your ideas with your group and decide on a final idea. -

Programming; Providing an Environment for the Growth and Education of Theatre Professionals, Audiences, and the Community at Large

JULY 2017 WELCOME MIKE HAUSBERG Welcome to The Old Globe and this production of King Richard II. Our goal is to serve all of San Diego and beyond through the art of theatre. Below are the mission and values that drive our work. We thank you for being a crucial part of what we do. MISSION STATEMENT The mission of The Old Globe is to preserve, strengthen, and advance American theatre by: creating theatrical experiences of the highest professional standards; producing and presenting works of exceptional merit, designed to reach current and future audiences; ensuring diversity and balance in programming; providing an environment for the growth and education of theatre professionals, audiences, and the community at large. STATEMENT OF VALUES The Old Globe believes that theatre matters. Our commitment is to make it matter to more people. The values that shape this commitment are: TRANSFORMATION Theatre cultivates imagination and empathy, enriching our humanity and connecting us to each other by bringing us entertaining experiences, new ideas, and a wide range of stories told from many perspectives. INCLUSION The communities of San Diego, in their diversity and their commonality, are welcome and reflected at the Globe. Access for all to our stages and programs expands when we engage audiences in many ways and in many places. EXCELLENCE Our dedication to creating exceptional work demands a high standard of achievement in everything we do, on and off the stage. STABILITY Our priority every day is to steward a vital, nurturing, and financially secure institution that will thrive for generations. IMPACT Our prominence nationally and locally brings with it a responsibility to listen, collaborate, and act with integrity in order to serve. -

The Role of the Theatre Audience: a Theory of Production and Reception

THE ROLE OF THE THEATRE AUDIENCE THE ROLE OF THE THEATRE AUDIENCE: A THEORY OF PRODUCTION AND RECEPTION By SUSAN BENNETT, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Parial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University January 1988 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (1988) McMASTER UNIVERSITY (English) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: The Role of the Theatre Audience: A Theory of Production and Reception AUTHOR: Susan Bennett, B.A. (University of Kent at Canterbury) M.A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Dr. Linda Hutcheon NUMBER OF PAGES: viii, 389 ii ABSTRACT Th thesis examines the reception of theatrical performanc by their audience. Its starting points are (i) Brech s dramatic theory and practice, and (ii) theories 0 reading. These indicate the main emphases of the th ,is--theoretical approaches and performance practices, rather than the more usual recourse to dramatic ;xts. Beyond Brecht and reader-response criticism, other studies of viewing are explored. Both semiotics lnd post-structuralism have stimulated an intensity )f interest in theatrical communication and such inves ~gations provide an important impetus for my work. In suggesting a theory of reception in the theatre, examine _theatre's cultural status and the assumption underlying what we recognize as the theatrical event. The selection of a particular performanc is explored and from this, it is suggested that there _s an inevitable, inextricable link between the produc ~ve and receptive processes. The theory then looks to lore immediate aspects of the performance, including 1e theatre building (its geographic location, architectu 11 style, etc.), the performance itself, and the post-p :formance rituals of theatre-going. -

Theatre of the Absurd : Its Themes and Form

THE THEATRE OF THE ABSURD: ITS THEMES AND FORM by LETITIA SKINNER DACE A. B., Sweet Briar College, 1963 A MASTER'S THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of Speech KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 1967 Approved by: c40teA***u7fQU(( rfi" Major Professor il PREFACE Contemporary dramatic literature is often discussed with the aid of descriptive terms ending in "ism." Anthologies frequently arrange plays under such categories as expressionism, surrealism, realism, and naturalism. Critics use these designations to praise and to condemn, to denote style and to suggest content, to describe a consistent tone in an author's entire ouvre and to dissect diverse tendencies within a single play. Such labels should never be pasted to a play or cemented even to a single scene, since they may thus stifle the creative imagi- nation of the director, actor, or designer, discourage thorough analysis by the thoughtful viewer or reader, and distort the complex impact of the work by suppressing whatever subtleties may seem in conflict with the label. At their worst, these terms confine further investigation of a work of art, or even tempt the critic into a ludicrous attempt to squeeze and squash a rounded play into a square pigeon-hole. But, at their best, such terms help to elucidate theme and illuminate style. Recently the theatre public's attention has been called to a group of avant - garde plays whose philosophical propensities and dramatic conventions have been subsumed under the title "theatre of the absurd." This label describes the profoundly pessimistic world view of play- wrights whose work is frequently hilarious theatre, but who appear to despair at the futility and irrationality of life and the inevitability of death. -

Hw Biography 2021

HUGH WOOLDRIDGE Director and Lighting Designer; Visiting Professor Hugh Wooldridge has produced, directed and devised theatre and television productions all over the world. He has taught and given master-classes in the UK, Europe, the US, South Africa and Australia. He trained at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art (LAMDA) and made his West End debut as an actor in The Dame of Sark with Dame Celia Johnson. Subsequently he performed with the London Festival Ballet / English National Ballet in the world premiere production of Romeo and Juliet choreographed by Rudolph Nureyev. At the age of 22, he directed The World of Giselle for Dame Ninette de Valois and the Royal Ballet. Since this time, he has designed lighting for new choreography with dance companies around the world including The Royal Ballet, Dance Theatre London, Rambert Dance Company, the National Youth Ballet and the English National Ballet Company. He directed the world premieres of the Graham Collier / Malcolm Lowry Jazz Suite Under A Volcano and The Undisput’d Monarch of the English Stage with Gary Bond portraying David Garrick; the Charles Strouse opera, Nightingale with Sarah Brightman at the Buxton Opera Festival; Francis Wyndham’s Abel and Cain (Haymarket, Leicester) with Peter Eyre and Sean Baker. He directed and lit the original award-winning Jeeves Takes Charge at the Lyric Hammersmith; the first productions of the Andrew Lloyd Webber and T. S. Eliot Cats (Sydmonton Festival), and the Andrew Lloyd Webber / Don Black song-cycle Tell Me 0n a Sunday with Marti Webb at the Royalty (now Peacock) Theatre; also Lloyd Webber’s Variations at the Royal Festival Hall (later combined together to become Song and Dance) and Liz Robertson’s one-woman show Just Liz compiled by Alan Jay Lerner at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London. -

The Sleeping Beauty

THE ROYAL BALLET APPROXIMATE TIMINGS DIRECTOR KEVIN O’HARE FOUNDER DAME NINETTE DE VALOIS om ch db e Live cinema relay begins at 7.15pm FOUNDER CHOREOGRAPHER Introduced by Darcey Bussell SIR FREDERICK ASHTON om ch cb e FOUNDER MUSIC DIRECTOR CONSTANT LAMBERT Prologue 33 minutes PRIMA BALLERINA ASSOLUTA Cinema interval DAME MARGOT FONTEYN db e Act I 31 minutes Cinema interval Acts II and III 70 minutes The performance will end at approximately 10.30pm THE SLEEPING Tweet your thoughts about tonight’s performance before it starts, during the interval or afterwards with #ROHbeauty BEAUTY BALLET IN A PROLOGUE AND THREE ACTS 2013/14 LIVE CINEMA SEASON THE WINTER’S TALE MONDAY 28 APRIL 2014 CHOREOGRAPHY MARIUS PETIPA ADDITIONAL CHOREOGRAPHY FREDERICK ASHTON, MANON LESCAUT TUESDAY 24 JUNE 2014 ANTHONY DOWELL, CHRISTOPHER WHEELDON MUSIC PYOTR IL’YICH TCHAIKOVSKY PRODUCTION MONICA MASON AND CHRISTOPHER NEWTON AFTER NINETTE DE VALOIS AND NICHOLAS SERGEYEV ROYAL OPERA HOUSE GUIDE TO ORIGINAL DESIGNS OLIVER MESSEL THE SLEEPING BEAUTY ADDITIONAL DESIGNS PETER FARMER LIGHTING DESIGN MARK JONATHAN Royal Opera House Guides contain specially selected films, STAGING CHRISTOPHER CARR articles, pictures, updates and exclusives to bring you closer to BALLET MASTER GARY AVIS the production. By purchasing your digital guide you can explore BALLET MISTRESS SAMANTHA RAINE the background to The Sleeping Beauty, the history of The Royal PRINCIPAL COACHING ALEXANDER AGADZHANOV, LESLEY COLLIER, JONATHAN COPE, MONICA MASON, CHRISTOPHER NEWTON Ballet’s production and -

The Dismembered Body in Antonin Artaud's Surrealist Plays

CHAPTER TWO THE DISMEMBERED BODY IN ANTONIN ARTAUD’S SURREALIST PLAYS THOMAS CROMBEZ In two of his surrealist plays, Antonin Artaud inserted a scene where human limbs rain down on the stage. The beginning of Le Jet de sang (The Spurt of Blood, 1925) features a young couple pathetically declaring their love for one another, when suddenly a hurricane bursts, two stars collide, and “a series of legs of living flesh fall down, together with feet, hands, heads of hair, masks, colonnades, portals, temples, and distilling flasks”1 (Artaud 1976a, 71). In a later scenario prepared for the Theatre of Cruelty project, La Conquête du Mexique (The Conquest of Mexico, 1933), the volley of human limbs is echoed almost verbatim. Human limbs, cuirasses, heads, and bellies fall down from all levels of the stage set, like a hailstorm that bombards the earth with supernatural explosions.2 (Artaud 1979, 23) These literal and, according to the theatrical conventions of the day, almost unstageable instances of “dismemberment in drama” point to a distinctive characteristic of Artaud’s work. He seemed to strive for a purely mental drama, to be staged for the enjoyment of the mind’s eye. The distinctly appropriative method he employed to write his mental play- texts may be labeled, borrowing an expression from Alfred Jarry studies, as “the systematically wrong style” (Jarry 1972, 1158). This expression has already proven its worth as the most concise term for Jarry’s linguistically grotesque plays, composed of Shakespearean drama, vulgar talk, heraldic language, archaisms, and corny schoolboy humor. The first part of my essay considers why the standard poststructuralist interpretation of Artaud’s œuvre is unable to provide a strictly literal reading of the human body parts that litter the stage. -

Islamic State & the Theatre of Cruelty

TILBURG ISLAMIC STATE & THE UNIVERSITY THEATRE OF CRUELTY Parallels between the Islamic State & Artaudian Theatre Thesis Algemene Cultuurwetenschappen BA | LPW Driessen The Islamic State and the Theatre of Cruelty Parallels between the Islamic State & Artaudian Theatre by Lennart Driessen S577263 Bachelorthesis ACW Tilburg University - School of humanities Under the supervision of: Jan Jaap de Ruiter 2 "If the attacks on the Twin Towers used the iconography of the Hollywood action blockbuster, the beheadings in the desert evoke drama far more ancient – Old Testament strife, Hellenic legend. [..]It may sound unlikely, but ISIS is carrying out in extremis the program of the “theatre of cruelty” of the influential French dramaturge- demiurge Antonin Artaud." - Joji Sakurai for Yale Global "Artaud, a sickly child twisted further by the shock of World War I, wanted his actors to “assault the senses” of the audience, shocking parts of the psyche that other theatrical methods had failed to reach. Well, IS has read the book. It’s been obvious since September 11 that we’re living in an age of vicious political theater. That’s what “terrorism” is: the manipulation of large populations by shock and awe and “liberating unconscious emotions”" -Hugh Prysor-Jones for Chronicles Magazine 3 Index Introduction..............................................................................................................................p.5 Chapter 1 - Hypothesis and methodology................................................................................p.7 -

Wojciechowski 1 Study Guide for Epic Theatre, Bertolt Brecht, the Theatre

Wojciechowski 1 Study Guide for Epic Theatre, Bertolt Brecht, the Theatre of the Absurd, and Friedrich Dürrenmatt 1. Define Epic Theatre. Theatrical movement from the early to mid-twentieth century that responded to the political climate of the time to a new political theater Erwin Piscator – German theater director Encouraged playwrights to address issues related to “contemporary existence” Staging: documentary effects (projections on screens), audience interaction, use of chorus The Epic Theatre was a reaction against the psychological realism in writing and staging associated with playwrights like Henrik Ibsen. At the same time, it recalls techniques employed by the Classical Greeks, like Euripides. One of the goals of Epic Theatre was to remove the audience from being emotionally involved in the characters so that they could respond and be moved to action by the message of the play. This involved a practice called verfremdungseffekt. 2. What is verfremdungseffekt? A. B. C. D. Why? 3. Some theatrical techniques (technical/performance) to achieve verfremdungseffekt: A. i. Origin: Classical theater B. i. Origin: Classical theater Wojciechowski 2 ii. long soliloquies that are narrative and self-revelatory C. i. light the house as well as the stage ii. place lighting equipment on the stage D. i. play characters believably without convincing either themselves or the audience that they have “become” the characters 4. Some dramatic techniques to achieve verfremdungseffekt: A. B. i. Notes describe minimalistic staging. ii. Stage directions do not describe psychological characterization – only physical. C. D. E. F. 5. The Epic Theatre movement was most developed by Bertolt Brecht; who is he? A.