Chapter One a Theoretical Background to the Figure of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Didactic Fragmentation in ''Scenes from the Big Picture'

Didactic Fragmentation in ”Scenes from the Big Picture” (2003) by Owen McCafferty Virginie Privas-Bréauté To cite this version: Virginie Privas-Bréauté. Didactic Fragmentation in ”Scenes from the Big Picture” (2003) by Owen McCafferty. 2012. halshs-01071477 HAL Id: halshs-01071477 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01071477 Preprint submitted on 5 Oct 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. !1 Didactic Fragmentation in Scenes from the Big Picture (2003) by Owen McCafferty Virginie Privas-Bréauté Université Jean Moulin - Lyon 3 Brecht’s dramatic theory helps demonstrate that the contours of contemporary Northern Irish drama have been reshaped. In this respect, Owen McCafferty’s play Scenes from the Big Picture has Neo-Brechtian resonances. The audience is presented with frag- ments of lives of people, bits and pieces of a whole picture. This play exemplifies Brecht’s idea of a didactic play in so far as the audience is called to learn about the Northern Irish Troubles from the play through the device of fragmentation: the uneven background of McCafferty’s play – i.e. the Troubles – is peopled with traumatised indi- viduals, proportionally fragmented. -

Strategies of Political Theatre Post-War British Playwrights

Strategies of Political Theatre Post-War British Playwrights Michael Patterson published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building,Trumpington Street,Cambridge cb2 1rp,United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building,Cambridge, cb2 2ru,UK 40 West 20th Street,New York, ny 10011–4211,USA 477 Williamstown Road,Port Melbourne, vic 3207,Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid,Spain Dock House,The Waterfront,Cape Town 8001,South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Cambridge University Press 2003 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2003 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press,Cambridge Typefaces Trump Mediaeval 9.25/14 pt. and Schadow BT System LATEX 2ε [tb] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn 0 521 25855 3 hardback Contents Acknowledgments ix Brief chronology, 1953–1989 x Introduction 1 Part 1: Theory 1 Strategies of political theatre: a theoretical overview 11 Part 2: Two model strategies 2 The ‘reflectionist’ strategy: ‘kitchen sink’ realism in Arnold Wesker’s Roots (1959) 27 3 The ‘interventionist’ strategy: poetic politics in John Arden’s Serjeant Musgrave’s Dance (1959) 44 Part 3: The reflectionist strain 4 The dialectics of comedy: Trevor Griffiths’s Comedians (1975) 65 5 Appropriating middle-class comedy: Howard Barker’s Stripwell -

The Theatre of the Real Yeats, Beckett, and Sondheim

The Theatre of the Real MMackenzie_final4print.indbackenzie_final4print.indb i 99/16/2008/16/2008 55:40:32:40:32 PPMM MMackenzie_final4print.indbackenzie_final4print.indb iiii 99/16/2008/16/2008 55:40:50:40:50 PPMM The Theatre of the Real Yeats, Beckett, and Sondheim G INA MASUCCI MACK ENZIE THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS • COLUMBUS MMackenzie_final4print.indbackenzie_final4print.indb iiiiii 99/16/2008/16/2008 55:40:50:40:50 PPMM Copyright © 2008 by Th e Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data MacKenzie, Gina Masucci. Th e theatre of the real : Yeats, Beckett, and Sondheim / Gina Masucci MacKenzie. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978–0–8142–1096–3 (cloth : alk. paper)—ISBN 978–0–8142–9176–4 (cd-rom) 1. English drama—Irish authors—History and criticism—Th eory, etc. 2. Yeats, W. B. (William Butler), 1865–1939—Dramatic works. 3. Beckett, Samuel, 1906–1989—Dramatic works. 4. Sondheim, Stephen—Criticism and interpretation. 5. Th eater—United States—History— 20th century. 6. Th eater—Great Britain—History—20th century. 7. Ireland—Intellectual life—20th century. 8. United States—Intellectual life—20th century. I. Title. PR8789.M35 2008 822.009—dc22 2008024450 Th is book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978–0–8142–1096–3) CD-ROM (ISBN 978–0–8142–9176–4) Cover design by Jason Moore. Text design by Jennifer Forsythe. Typeset in Adobe Minion Pro. Printed by Th omson-Shore, Inc. Th e paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. -

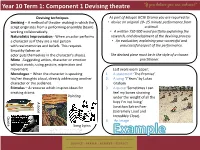

Year 10 Term 1: Component 1 Devising Theatre

Year 10 Term 1: Component 1 Devising theatre Devising techniques As part of Eduqas GCSE Drama you are required to: Devising – A method of theatre- making in which the • devise an original 10- 15 minute performance from script originates from a performing ensemble (team) a stimuli working collaboratively. • A written 750-900 word portfolio explaining the Naturalistic Improvisation - When an actor performs research, and development of the devising process. a character as if they are a real person • An evaluation, explaining your successful and with real memories and beliefs. This requires unsuccessful aspect of the performance. Empathy (when an actor puts themselves in the character’s shoes). The devised piece must be in the style of a chosen Mime -Suggesting action, character or emotion practitioner. without words, using gesture, expression and movement. Last years exam paper: Monologue – When the character is speaking 1. A statement ‘The Promise’ his/her thoughts aloud, directly addressing another 2. A song ‘7 Years’ by Lukas character or the audience. Graham Stimulus – A recourse which inspires ideas for 3. A quote ‘Sometimes I can creating drama. feel my bones straining Painting under the weight of all the A book lives I’m not living’ Jonathan Safran Foer (Extremely Loud and Quote Incredibly Close). 4. An Image Song Lyrics Year 10 Term 1: Component 1 Devising Theatre Research- Explore each stimuli, finding out all the A sequence in a chronological order fact around it. including a beginning, middle and end. Map ideas – Write all your initial ideas on a mind map. Discuss – Share your ideas with your group and decide on a final idea. -

Programming; Providing an Environment for the Growth and Education of Theatre Professionals, Audiences, and the Community at Large

JULY 2017 WELCOME MIKE HAUSBERG Welcome to The Old Globe and this production of King Richard II. Our goal is to serve all of San Diego and beyond through the art of theatre. Below are the mission and values that drive our work. We thank you for being a crucial part of what we do. MISSION STATEMENT The mission of The Old Globe is to preserve, strengthen, and advance American theatre by: creating theatrical experiences of the highest professional standards; producing and presenting works of exceptional merit, designed to reach current and future audiences; ensuring diversity and balance in programming; providing an environment for the growth and education of theatre professionals, audiences, and the community at large. STATEMENT OF VALUES The Old Globe believes that theatre matters. Our commitment is to make it matter to more people. The values that shape this commitment are: TRANSFORMATION Theatre cultivates imagination and empathy, enriching our humanity and connecting us to each other by bringing us entertaining experiences, new ideas, and a wide range of stories told from many perspectives. INCLUSION The communities of San Diego, in their diversity and their commonality, are welcome and reflected at the Globe. Access for all to our stages and programs expands when we engage audiences in many ways and in many places. EXCELLENCE Our dedication to creating exceptional work demands a high standard of achievement in everything we do, on and off the stage. STABILITY Our priority every day is to steward a vital, nurturing, and financially secure institution that will thrive for generations. IMPACT Our prominence nationally and locally brings with it a responsibility to listen, collaborate, and act with integrity in order to serve. -

The Role of the Theatre Audience: a Theory of Production and Reception

THE ROLE OF THE THEATRE AUDIENCE THE ROLE OF THE THEATRE AUDIENCE: A THEORY OF PRODUCTION AND RECEPTION By SUSAN BENNETT, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Parial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University January 1988 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (1988) McMASTER UNIVERSITY (English) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: The Role of the Theatre Audience: A Theory of Production and Reception AUTHOR: Susan Bennett, B.A. (University of Kent at Canterbury) M.A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Dr. Linda Hutcheon NUMBER OF PAGES: viii, 389 ii ABSTRACT Th thesis examines the reception of theatrical performanc by their audience. Its starting points are (i) Brech s dramatic theory and practice, and (ii) theories 0 reading. These indicate the main emphases of the th ,is--theoretical approaches and performance practices, rather than the more usual recourse to dramatic ;xts. Beyond Brecht and reader-response criticism, other studies of viewing are explored. Both semiotics lnd post-structuralism have stimulated an intensity )f interest in theatrical communication and such inves ~gations provide an important impetus for my work. In suggesting a theory of reception in the theatre, examine _theatre's cultural status and the assumption underlying what we recognize as the theatrical event. The selection of a particular performanc is explored and from this, it is suggested that there _s an inevitable, inextricable link between the produc ~ve and receptive processes. The theory then looks to lore immediate aspects of the performance, including 1e theatre building (its geographic location, architectu 11 style, etc.), the performance itself, and the post-p :formance rituals of theatre-going. -

Wojciechowski 1 Study Guide for Epic Theatre, Bertolt Brecht, the Theatre

Wojciechowski 1 Study Guide for Epic Theatre, Bertolt Brecht, the Theatre of the Absurd, and Friedrich Dürrenmatt 1. Define Epic Theatre. Theatrical movement from the early to mid-twentieth century that responded to the political climate of the time to a new political theater Erwin Piscator – German theater director Encouraged playwrights to address issues related to “contemporary existence” Staging: documentary effects (projections on screens), audience interaction, use of chorus The Epic Theatre was a reaction against the psychological realism in writing and staging associated with playwrights like Henrik Ibsen. At the same time, it recalls techniques employed by the Classical Greeks, like Euripides. One of the goals of Epic Theatre was to remove the audience from being emotionally involved in the characters so that they could respond and be moved to action by the message of the play. This involved a practice called verfremdungseffekt. 2. What is verfremdungseffekt? A. B. C. D. Why? 3. Some theatrical techniques (technical/performance) to achieve verfremdungseffekt: A. i. Origin: Classical theater B. i. Origin: Classical theater Wojciechowski 2 ii. long soliloquies that are narrative and self-revelatory C. i. light the house as well as the stage ii. place lighting equipment on the stage D. i. play characters believably without convincing either themselves or the audience that they have “become” the characters 4. Some dramatic techniques to achieve verfremdungseffekt: A. B. i. Notes describe minimalistic staging. ii. Stage directions do not describe psychological characterization – only physical. C. D. E. F. 5. The Epic Theatre movement was most developed by Bertolt Brecht; who is he? A. -

Come up to the Lab a Sciart Special

024 on tourUK DRAMA & DANCE 2004 COME UP TO THE LAB A SCIART SPECIAL BOBBY BAKER_RANDOM DANCE_TOM SAPSFORD_CAROL BROWN_CURIOUS KIRA O’REILLY_THIRD ANGEL_BLAST THEORY_DUCKIE CHEEK BY JOWL_QUARANTINE_WEBPLAY_GREEN GINGER CIRCUS_DIARY DATES_UK FESTIVALS_COMPANY PROFILES On Tour is published bi-annually by the Performing Arts Department of the British Council. It is dedicated to bringing news and information about British drama and dance to an international audience. On Tour features articles written by leading and journalists and practitioners. Comments, questions or feedback should be sent to FEATURES [email protected] on tour 024 EditorJohn Daniel 20 ‘ALL THE WORK I DO IS UNCOMPLETED AND Assistant Editor Cathy Gomez UNFINISHED’ ART 4 Dominic Cavendish talks to Declan TheirSCI methodologies may vary wildly, but and Third Angel, whose future production, Donnellan about his latest production Performing Arts Department broadly speaking scientists and artists are Karoshi, considers the damaging effects that of Othello British Council WHAT DOES LONDON engaged in the same general pursuit: to make technology might have on human biorhythms 10 Spring Gardens SMELL LIKE? sense of the world and of our place within it. (see pages 4-7). London SW1A 2BN Louise Gray sniffs out the latest projects by Curious, In recent years, thanks, in part, to funding T +44 (0)20 7389 3010/3005 Kira O’Reilly and Third Angel Meanwhile, in the world of contemporary E [email protected] initiatives by charities like The Wellcome Trust dance, alongside Wayne McGregor, we cover www.britishcouncil.org/arts and NESTA (the National Endowment for the latest show from Carol Brown, which looks COME UP TO Science, Technology and the Arts), there’s THE LAB beyond the body to virtual reality, and Tom Drama and Dance Unit Staff 24 been a growing trend in the UK to narrow the Lyndsey Winship Sapsford, who’s exploring the effects of Director of Performing Arts THEATRE gap between arts and science professionals John Kieffer asks why UK hypnosis on his dancers (see pages 9-11). -

A Study of the Royal Court Young Peoples’ Theatre and Its Development Into the Young Writers’ Programme

Building the Engine Room: A Study of the Royal Court Young Peoples’ Theatre and its Development into the Young Writers’ Programme N O Holden Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Building the Engine Room: A Study of the Royal Court’s Young Peoples’ Theatre and its Development into the Young Writers’ Programme Nicholas Oliver Holden, MA, AKC A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Lincoln for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Fine and Performing Arts College of Arts March 2018 2 DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for a higher degree elsewhere. 3 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisors: Dr Jacqueline Bolton and Dr James Hudson, who have been there with advice even before this PhD began. I am forever grateful for your support, feedback, knowledge and guidance not just as my PhD supervisors, but as colleagues and, now, friends. Heartfelt thanks to my Director of Studies, Professor Mark O’Thomas, who has been a constant source of support and encouragement from my years as an undergraduate student to now as an early career academic. To Professor Dominic Symonds, who took on the role of my Director of Studies in the final year; thank you for being so generous with your thoughts and extensive knowledge, and for helping to bring new perspectives to my work. My gratitude also to the University of Lincoln and the School of Fine and Performing Arts for their generous studentship, without which this PhD would not have been possible. -

Modern Drama: an Overview

Tikrit University College of Education English Department Modern Drama Dr. Awfa Hussein Al-Doory, PhD Modern Drama: An Overview The birth of modern drama dates back to the 20th century which encompasses different playwright with different styles and techniques. The age of modern drama is an age of (isms) that is the emergence of different literary schools which influence the way subject matters are tackled and represented. One of the most common features of modern drama is that of realism. Earlier years of the 20th century witnessed an interest in realistic tendency which endeavors to deal and reflect on real problems of life. Modern drama, in this sense, aims at presenting life as it is. It was Henrik Ibsen, the Norwegian playwright, who popularized realism and drama of ideas in modern theatre. As a realist playwright, Ibsen employs theatre as a means for tackling realistic subject matters like marriage, justice, law, social conflicts, and the like; he (Ibsen) is significantly considered a social reformer because of tackling such realistic subject matters. Ibsen's play A Doll's House is a good example of realistic drama. Naturalism is an extreme realism. This movement suggested the roles of family, social conditions, and environment in shaping human character. Thus, naturalistic writers write stories based on the idea that environmental forces determine man's fate and make him act and react in a particular way. Generally, naturalistic works expose dark sides of life such as prejudice, racism, poverty, prostitution, filth, and disease. Despite the echoing pessimism in this literary output, naturalists are generally concerned with improving human conditions around the world. -

Book of Abstracts

ABSTRACTS AND BIOGRAPHIES Thursday, October 11, 2018 9.45 PANEL: Across Languages Chair: Claire Hélie (Lille University) 1. Maggie Rose (Milan University) Importing new British plays to Italy. Rethinking the role of the theatre translator Over the last three decades I have worked as a co-translator and a cultural mediator between the UK and Italy, bringing plays by Alan Bennett, Edward Bond, Caryl Churchill, Claire Dowie, David Greig, Kwame Kwei-Armah, Hanif Kureishi, Liz Lochhead, Sabrina Mahfouz, Rani Moorthy, among others,to the Italian stage. Bearing in mind a complex web of Italo-British relations, I will discuss how my strategies of cultural mediation have evolved over the years as a response to significant changes in the two theatre systems. I will explore why the task of finding a publisher and a producer\director for some British authors has been more difficult than for others, the stage and critical success of certain dramatists in Italy more limited. I will look specifically at the Italian ‘journeys’ of the following writers: Caryl Churchill and my co-translation of Top Girls (1986) and A Mouthful of Birds, Edward Bond and my co-translation of The War Plays for the 2006 Winter Olympics in Turin and Alan Bennett and my co-translation of The History Boys at Teatro Elfo Pucini from 2011-3013, at Teatro Elfo Puccini and national tours. Maggie Rose teaches British Theatre Studies and Performance at the University of Milan and spends part of the year in the UK for her writing and research. She is a member of the Scottish Society of Playwrights and her plays have been performed in the UK and in Italy. -

Sydney Theatre Company Annual Report 2011 Annual Report | Chairman’S Report 2011 Annual Report | Chairman’S Report

2011 SYDNEY THEATRE COMPANY ANNUAL REPORT 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | CHAIRMAn’s RepoRT 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | CHAIRMAn’s RepoRT 2 3 2011 ANNUAL REPORT 2011 ANNUAL REPORT “I consider the three hours I spent on Saturday night … among the happiest of my theatregoing life.” Ben Brantley, The New York Times, on STC’s Uncle Vanya “I had never seen live theatre until I saw a production at STC. At first I was engrossed in the medium. but the more plays I saw, the more I understood their power. They started to shape the way I saw the world, the way I analysed social situations, the way I understood myself.” 2011 Youth Advisory Panel member “Every time I set foot on The Wharf at STC, I feel I’m HOME, and I’ve loved this company and this venue ever since Richard Wherrett showed me round the place when it was just a deserted, crumbling, rat-infested industrial pier sometime late 1970’s and a wonderful dream waiting to happen.” Jacki Weaver 4 5 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | THROUGH NUMBERS 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | THROUGH NUMBERS THROUGH NUMBERS 10 8 1 writers under commission new Australian works and adaptations sold out season of Uncle Vanya at the presented across the Company in 2011 Kennedy Center in Washington DC A snapshot of the activity undertaken by STC in 2011 1,310 193 100,000 5 374 hours of theatre actors employed across the year litre rainwater tank installed under national and regional tours presented hours mentoring teachers in our School The Wharf Drama program 1,516 450,000 6 4 200 weeks of employment to actors in 2011 The number of people STC and ST resident actors home theatres people on the payroll each week attracted into the Walsh Bay precinct, driving tourism to NSW and Australia 6 7 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | ARTISTIC DIRECTORs’ RepoRT 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | ARTISTIC DIRECTORs’ RepoRT Andrew Upton & Cate Blanchett time in German art and regular with STC – had a window of availability Resident Artists’ program again to embrace our culture.