Cookbooks As Edible Adventures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pride in Glynn County Seafood Cookbook

PRIDE IN GLYNN COUNTY SEAFOOD COOKBOOK RECIPES, STORIES, AND FACTS ABOUT FOOD PRIDE IN GLYNN COUNTY SEAFOOD COOKBOOK RECIPES, STORIES, AND FACTS ABOUT FOOD ACKNOWLEDGMENTS INTRODUCTION People who live around Brunswick love nothing better than a good We thank the many fishers, crabbers, shrimpers and consumers seafood dish, and they also love to talk about a great seafood of seafood who have lived in and around Glynn County over dish! We are blessed to live near a saltwater marsh that is home to a bountiful fish population. The marsh and fishing have been hundreds of years, and who have celebrated our rich and part of our community’s long history and are celebrated today by diverse culture, especially our food! local chefs, festivals, family get-togethers and church fish dinners. We thank all of our neighbors who contributed their art and We asked some of our favorite local cooks to share their recipes taste for this first “Pride in Glynn County” cookbook. We thank and stories. Some cook for a living; others for the pure joy of it. Honeywell for its financial support. We thank our co-workers We invite you to explore the recipes found in our first “Pride in from the Environmental Justice Advisory Board, Rebuilding Glynn County Seafood Cookbook” and try new ways to enjoy Together – Brunswick and the University of Georgia Marine fresh local fish. The University of Georgia Marine Extension and Extension and Georgia Sea Grant who supported us and Georgia Sea Grant offers tips for safe and healthy ways to provided endless feedback on how to create a resource that prepare the catch of the day. -

Community Cookbook

Community Cookbook Curated by Sienna Fekete Designed by Rin Kim Ni Illustrations by Shireen Alia Ahmed This community cookbook was conceptualized as a way to bring together cherished recipes, the memories, traditions and family legacies we carry with them, and make folks feel a little more connected to one another. Inspired by the history of community cookbooks as a tool for community reciprocity and skill-sharing, I know food to be a great unifier. I grew up with an immense love for food, discovering new tastes and textures, and the creative possibility of food—without an extensive knowledge of the practice of cooking itself nor a way around the kitchen. This is my way of learning and exploring food together with my community and creating a community-generated resource that hopefully will inspire us all to learn from each other and try out some new things. Dedicated to my twelve-year-old self, a novice yet ambitious food-lover and all the folks who showed me about the power of good food <3 - Sienna Fekete 3 Table of Contents: Side Dishes / Dips / Spreads / Breads Main Dishes 10-11 Lima Bean Masabeha - Gal Amit 48-49 Sunday Shakshuka - Margot Bowman 12-13 Jawole’s Momma’s Grandmother’s White Beans - Jawole Willa Jo Zollar Teochew Chive Dumplings - Vanessa Holyoak 50-51 14-15 Family Scones - Vanessa Gaddy Harissa Chickpea Bowl With Potatoes, Lemon-y Tahini & Greens - 52-53 Anna Santangelo 16-17 Maya’s New Mexican Hatch Chili Cornbread - Maya Contreras 54-55 Kousa Mashi - Sanna Almajedi 18-19 Muhammara Traditional Arabic Red Pepper and Walnut -

Page 1 DOCUMENT RESUME ED 335 965 FL 019 564 AUTHOR

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 335 965 FL 019 564 AUTHOR Riego de Rios, Maria Isabelita TITLE A Composite Dictionary of Philippine Creole Spanish (PCS). INSTITUTION Linguistic Society of the Philippines, Manila.; Summer Inst. of Linguistics, Manila (Philippines). REPORT NO ISBN-971-1059-09-6; ISSN-0116-0516 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 218p.; Dissertation, Ateneo de Manila University. The editor of "Studies in Philippine Linguistics" is Fe T. Otanes. The author is a Sister in the R.V.M. order. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Vocabularies/Classifications/Dictionaries (134)-- Dissertations/Theses - Doctoral Dissertations (041) JOURNAL CIT Studies in Philippine Linguistics; v7 n2 1989 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Creoles; Dialect Studies; Dictionaries; English; Foreign Countries; *Language Classification; Language Research; *Language Variation; Linguistic Theory; *Spanish IDENTIFIERS *Cotabato Chabacano; *Philippines ABSTRACT This dictionary is a composite of four Philippine Creole Spanish dialects: Cotabato Chabacano and variants spoken in Ternate, Cavite City, and Zamboanga City. The volume contains 6,542 main lexical entries with corresponding entries with contrasting data from the three other variants. A concludins section summarizes findings of the dialect study that led to the dictionary's writing. Appended materials include a 99-item bibliography and materials related to the structural analysis of the dialects. An index also contains three alphabetical word lists of the variants. The research underlying the dictionary's construction is -

Price List by Cuisine

PRICE LIST BY CUISINE INDIAN PROMO SET CODE: DP01 Min order:30 pax Plain Rice Madras Mutton Masala Chicken Varuval Mutton Kofta Gobi Fry Cucumber Raita Dalcha Chilled Orange Cordial RM29.00/pax CODE: DP04 Min order: 30 pax Biryani Rice Chicken Manchuri Paratha Chicken Karahi Rogan Gosht (Lamb) Fish Curry Iced Cold Lime Syrup RM30.00/pax CODE: DP07 Min order: 30 pax (VEGETARIAN) Plain Rice Chapati Bhindi Fry Mixed Vegetable Bhaji Cauliflower Tikka Massala Dalchar Ice Cold Ice Lemon Tea RM19.00/pax CODE: DP02 Min order: 30 pax Plain Rice Butter Chicken Masala Mutton Vindaloo Cucumber Raita Mixed Vegetable Jalfrezi Dalchar Pappadom Ice Cold Citrus Lime Drink RM24.00/pax CODE: DP05 Min order: 30 pax Plain Rice Chicken 65 Fish Sambal Dalcha Bhuna Gosht Fried Turmeric Okra Ice Cold Citrus Lime Drink RM26.00/pax CODE: DP03 Min order: 30 pax Ghee Rice Chicken Tika Masala Chapati Bhuna Gosht (Lamb) Tandoori Fish Green Mix Salad Aloo Ghobi Iced Cold Lemon Cordial RM29.00/pax CODE: DP06 Min order: 30 pax (VEGETARIAN) Gobhi Manchurian Ghee Rice Vegetable Curry Paratha Dalchar Aloo Jeera Ice Cold Citrus Lime Drink RM20.00/pax MALAY PROMO SET CODE: DS10 Plain Rice Fish Sambal Pineapple Prawn Curry Ayam Masak Merah Fried Tempe and Tofu Kailan Ikan Masin Fruit Platter Kuih Seri Muka Potato Curry Puff Iced Cold Mango Cordial RM32.00/pax CODE: DS11 Plain Rice Ayam Masak Lemak Kari Kambing Ikan Masak Masam Manis Kailan Oyster Sauce Mixed Fruits Salted Fish Salted Egg Sambal Belacan Kuih Seri Muka Vegetable Spring Roll Ice Cold Orange- Syrup RM36.00/pax CODE:DS12 -

History of Fermented Black Soybeans 1

HISTORY OF FERMENTED BLACK SOYBEANS 1 HISTORY OF FERMENTED BLACK SOYBEANS (165 B.C. to 2011): EXTENSIVELY ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY AND SOURCEBOOK USED TO MAKE BLACK BEAN SAUCE. ALSO KNOW AS: FERMENTED BLACK BEANS, SALTED BLACK BEANS, FERMENTED SOYBEANS, PRESERVED BLACK BEANS, SALTY BLACK BEANS, BLACK FERMENTED BEANS, BLACK BEANS; DOUCHI, DOUSHI, TOUSHI, TOU-CH’IH, SHI, SHIH, DOW SEE, DOWSI (CHINESE); HAMANATTO, DAITOKUJI NATTO (JAPANESE); TAUSI, TAOSI (FILIPINO) Compiled by William Shurtleff & Akiko Aoyagi 2011 Copyright © 2011 by Soyinfo Center HISTORY OF FERMENTED BLACK SOYBEANS 2 Copyright (c) 2011 by William Shurtleff & Akiko Aoyagi All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means - graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or information and retrieval systems - except for use in reviews, without written permission from the publisher. Published by: Soyinfo Center P.O. Box 234 Lafayette, CA 94549-0234 USA Phone: 925-283-2991 Fax: 925-283-9091 www.soyinfocenter.com [email protected] ISBN 978-1-928914-41-9 (Fermented Black Soybeans) Printed 11 Dec. 2011 Price: Available on the Web free of charge Search engine keywords: History of fermented black soybeans History of fermented black beans History of Hamanatto History of Hamananatto History of black bean sauce History of shi History of shih History of salted black beans History of fermented soybeans History of douchi History of doushi History of preserved soybeans History of dow see History of tausi -

UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Agrarian Pasts, Utopian Futures : : Food, Nostalgia, and the Power of Dreaming in Old Comedy and the New Southern Food Movement Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7tg32193 Author Kelting, Lily Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Agrarian Pasts, Utopian Futures: Food, Nostalgia, and the Power of Dreaming in Old Comedy and the New Southern Food Movement A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Drama and Theatre by Lily Kelting Committee in charge: University of California, San Diego Professor Nadine George-Graves, Chair Professor Page duBois, Co-chair Professor Patrick Anderson Professor Anthony Edwards Professor Marianne McDonald University of California, Irvine Professor Daphne Lei 2014 Copyright Lily Kelting, 2014 All rights reserved. Signature Page The Dissertation of Lily Kelting is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Co-chair Chair University of California, San Diego University of California, Irvine 2014 iii Table of Contents Signature Page ............................................................................................................... iii Table of Contents ......................................................................................................... -

Appetizers Signature Salads Classics Sides

TIBBY’S WINTER PARK TIBBY’S ALTAMONTE TIBBY’S BRANDON 2203 Aloma Ave 494 FL-436 1721 W Brandon Blvd Winter Park, FL 32792 Altamonte Springs, FL 32714 Brandon, FL 33511 Appetizers BBQ SHRIMP NEW ORLEANS CHEESE PLANK MUFFULETTA SPRING ROLLS Large natural Gulf shrimp, butter, beer & Crispy coated pepper jack cheese, Stuffed with salami, mortadella, ham, spices. Served with French bread. 14.95 lightly fried & served over our Creole Swiss & provolone cheese, olive salad. sauce. 5.95 Side of Creole dijonnaise. 7.50 ONION RING STACK Thick-cut & hand-battered. Side of MAW’S FRIES POTATO SKINS remoulade sauce. 6.50 Fries smothered with our slow-cooked Four potato skins topped with Andouille roast beef “debris” gravy. Loaded with sausage, peppered bacon & pepper SHRIMP & ALLIGATOR CHEESECAKE cheese. 9.95 jack cheese. Served with a side of sour Natural Gulf shrimp, alligator meat, cream & remoulade sauce. 7.95 three cheeses, panko crumbs. 11.95 BOUDIN ROLLS Lightly fried spring rolls stuffed with FRIED GREEN TOMATOES CAJUN WINGS boudin & jack cheese. Served with & CRAWFISH Tossed in house-made Louisiana Gold creole dijonnaise. 7.95 Hand-battered green tomatoes, hot sauce. Side of blue cheese. 9.95 popcorn-style crawfish & remoulade DEBRIS SPRING ROLLS sauce. 9.25 GATOR BITES Stuffed with our slow-cooked roast beef Hand-battered and fried crispy. Served debris and Manchego cheese. Served with our famous remoulade sauce. 11.95 with a side of roast beef gravy. 5.95 Classics by the cup FRIED PICKLE SLICES Hand-battered. Side of remoulade. 5.75 SLOW-COOKED RED BEANS & RICE Cooked over 8 hours with ham and topped with hot sausage. -

Themed Cocktail Stations

THEMED STATIONS (See Package Highlights for Selections) A STROLL IN NEW DELHI (Select 3 of the Following) Station Includes: Spiced Basmati Rice Chicken Tikka Masala Tender Morsels of Chicken Simmered in a Traditional Spicy Tomato Sauce Chicken Tandoori Yogurt & Curry Marinated Bone-in Chicken, Flame Grilled with BBQ Ripe Plum Tomatoes Spicy Mango Chicken Curry Breasts of Chicken Prepared with Sweet Spiced Mangos and Coconut Milk Bhindi Masala Fresh Cut Okra Sautéed in Gravy with Aromatic Spices Vegetable Curry Fresh Vegetables Stir-Fried with Light Yogurt, Coriander & Cumin Mediterranean (Select 3 of the Following) Station Includes: Garlic Hummus & Pita Wedges Rosemary Lamb Skewers with White Basmati Rice Chicken Souvlaki Skewers Marinated in Garlic, Extra Virgin Olive Oil, Oregano & Lemon Juice Arroz Con Pollo Chicken Simmered with Onions, Garlic Tomatoes and Rice Chicken Athenian Herb-Marinated Chicken with Garlic, Feta, White Wine & Lemon mussels Posillipo Tomatoes, Garlic, Fresh Herbs with a White Wine Broth Corsica Pasta Penne Pasta Sautéed with Sundried Tomatoes, Feta Cheese, Artichoke Hearts, Garlic, Extra Virgin Olive Oil Clams Oreganata Baked in the Half-Shell Topped with Bread Crumbs and Oregano 8 THEMED STATIONS (See Package Highlights for Selections) MEMPHIS BBQ (Select 2 of the Following) Station Includes: Homemade Corn Bread & Baked Beans Smoked Braised Pork Bellies Served on a Bed of Pear Slaw PULLED PORK SLIDERS BBQ CHICKEN Mystic Grilled Chicken with BBQ Sauce CHICKEN GUMBO Served over White Rice COUNTRY FRIED CHICKEN -

Arsenic in Rice and Rice Products Risk Assessment Report

Arsenic in Rice and Rice Products Risk Assessment Report Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition Food and Drug Administration U.S. Department of Health and Human Services March 2016 Version Released for Public Comment CONTRIBUTORS Project Co-Leads: Sherri Dennis, PhD Suzanne Fitzpatrick, PhD, DABT Project Manager: Dana Hoffman-Pennesi, MS Risk Modelers: Clark Carrington, PhD, DABT (Retired April 2015) Régis Pouillot, DVM, PhD Subject Matter Experts: Katie Egan (Retired July 2013) Brenna Flannery, PhD Richard Kanwal, MD Deborah Smegal, MPH Judi Spungen, MS Shirley Tao, PhD Technical Writer/Editor: Susan Mary Cahill CITATION FOR THIS REPORT: U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2016. Arsenic in Rice and Rice Products Risk Assessment Report. Available at http://www.fda.gov/Food/FoodScienceResearch/RiskSafetyAssessment/default.htm. Arsenic in Rice and Rice Products Risk Assessment Report Progress: Risk Management Team Review: Draft Risk Assessment Report dated November 2013 Interagency Expert Review: Draft Risk Assessment Report dated December 2013 CFSAN/FDA Review/Clearance – Draft Risk Assessment Report dated February 2014 HHS Clearance – Draft Risk Assessment Report dated May 2014 OMB Review: Draft Risk Assessment Report dated May 2014 (revised April 2015) and Addendum to the May 2014 Risk Assessment Report (draft dated May 2015) External Peer Review: Draft Risk Assessment Report dated July 2015 and Addendum dated May 2015 Revised Report based on External Peer Review and Incorporation of Addendum: Risk Assessment Report dated October 2015 Revised Report based on additional comments from OMB: Risk Assessment Report dated December 2015 May 13, 2014 Arsenic in Rice and Rice Products Risk Assessment Report (Revised March 2016) | i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The FDA Arsenic in Rice and Rice Products Risk Assessment benefited from contributions, conversations, and information provided by many individuals, organizations, and government officials. -

Appetizers Signature Salads Classics

TIBBY’S WINTER PARK TIBBY’S ALTAMONTE TIBBY’S BRANDON 2203 Aloma Ave 494 FL-436 1721 W Brandon Blvd Winter Park, FL 32792 Altamonte Springs, FL 32714 Brandon, FL 33511 APPETIZERS BBQ SHRIMP FRIED PICKLE SLICES MUFFULETTA SPRING ROLLS Large natural Gulf shrimp, butter, beer & Hand-battered. Side of remoulade. 5.75 Stuffed with salami, mortadella, ham, spices. Served with French bread. 14.95 Swiss & provolone cheese, olive salad. NEW ORLEANS CHEESE PLANK Side of Creole dijonnaise. 7.50 ONION RING STACK Crispy coated pepper jack cheese, Thick-cut & hand-battered. Side of lightly fried & served over our Creole POTATO SKINS remoulade sauce. 6.50 sauce. 5.95 Four potato skins topped with Andouille sausage, peppered bacon & pepper SHRIMP & ALLIGATOR CHEESECAKE MAW’S FRIES jack cheese. Served with a side of sour Natural Gulf shrimp, alligator meat, Fries smothered with our slow-cooked cream & remoulade sauce. 7.95 three cheeses, panko crumbs. 11.95 roast beef “debris” gravy. Loaded with cheese. 9.95 FRIED GREEN TOMATOES CAJUN WINGS & CRAWFISH Tossed in house-made Louisiana Gold BOUDIN BALLS Hand-battered green tomatoes, hot sauce. Side of blue cheese. 9.95 Pork liver, long rice, cooked onions & popcorn-style crawfish & remoulade Cajun seasonings. Side of our Creole sauce. 8.95 sauce. 8.00 CLASSICS BY THE CUP SIGNATURE SALADS SLOW-COOKED RED CRAZY GREEK COUSIN’S BEANS & RICE CHOPPED SALAD Cooked over 8 hours with ham and Romaine, olive mix, sun-dried tomatoes, topped with hot sausage. 6.00 Greek peppers, cucumbers, red onions & trinity pico (diced onions & peppers) JAMBALAYA ADD A LITTLE tossed in our house Greek dressing. -

Cooking Light 2004 Annual Recipe Index

1 Cooking Light 2004 Annual Recipe Index G QUICK & EASY L MAKE AHEAD I FREEZABLE appetizers Shrimp and Fennel in Hot Garlic Asiago-Artichoke-Turkey Spread Nov 252 G Sauce Oct 170 G Baked Frittata Ribbons in Tomato Smoked Salmon Crostini Dec 98 L Sauce May 184 L Smoked Trout Spread Nov 230 G L Baked Hoisin Chicken Buns Sept 136 L Smoky Eggplant Puree with Black Bean Spread with Lime and Crostini Mar 179 L Cilantro Nov 230 G L Spanish Tortilla with Almond Blackened Shrimp with Romesco Apr 228 L Pomegranate-Orange Salsa Dec 104 Spiced Date-Walnut Snacks Nov 226 Bruschetta with Warm Tomatoes Aug 184 Spicy Fish Cakes Sept 159 G Caramelized Onion Dip Mar 206 L Spicy Shrimp and Scallop SevicheJuly 184 L Caramelized Onion, Red Pepper, Spinach-Parmesan Dip Nov 232 G L and Mushroom Pizzetti Dec 98 Spinach, Sun-Dried Tomato, and Cheddar with Sautéed Apples Parmesan Rolls Dec 102 and Brown Bread Dec 98 G Steamed Mussels with Cardamom, Cheese Dip with Crawfish Dec 100 G Orange, and Mint Sept 99 G Chipotle Shrimp Cups June 216 Steamed Pork Buns Apr 146 Cool and Crunchy Crab Dip Nov 232 G L Sun-Dried Tomato Cheesecake Sept 219 L Crab-and-Mango Empanadas Sweet Onion, White Bean, and (Empanadas de Cangrejo y Mango) Sept 226 Artichoke Dip Dec 203 G L Crab and Scallop Sui Mei Sept 222 L Tapenade Nov 232 G L Creamy Mushroom Spread Nov 230 G L Thai Shrimp Rolls with Julienne Crisp and Spicy Snack Mix J/F 124 G L of Vegetables Mar 227 Cumin Curried Hummus Nov 230 G L Tofu Larb Sept 130 Farmers’ Market Quesadillas Aug 145 G Tuna Tartare in Endive with Feta-Chile -

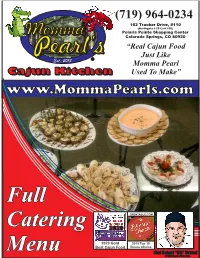

Full Catering Menu Full Catering Menu

(719) 964-0234 162 Tracker Drive, #110 (Northgate I-25 Exit 156) Momma Polaris Pointe Shopping Center Momma Colorado Springs, CO 80920 “Real Cajun Food PPearl’searl’s Just Like ® Est. 2013 Momma Pearl CajunCajun KitchenKitchen Used To Make” www.MommaPearls.com Full OPENTABLE.COM Catering 2020 2020 Gold 2019 Top 10 Best Cajun Food Diners Choice Menu Chef Robert “BB” Brunet PPCRA Board of Directors MommaMomma PPearl’searl’s App’s & Sides Est. 2013 ® CajunCajun KitchenKitchen Call (719) 964-0234 To Order All Catering Trays Setup To Serve 10 or More Guests Real Alligator Bites $94.50 Real Alligator Tenderloins hand-rolled in Creole Seasoned Batter and Deep Fried to Crispy Perfection served over a bed of French Fries Cornbread Hushpuppies $34.95 Deep Fried Corn Hushpuppies (Approx. 30 pieces) Cajun Boudain Sausage Crabmeat au Gratin Dip Savory Cajun Sausage made with Creamy Garlic & Spinach Crabmeat Rice, Chicken, and Pork $49.50 au Gratin Dip w/ Tortilla Chips $89.50 Crabstuffed Jumbo Portobelo Mushrooms made with real Crabmeat $76.95 Mushrooms and Cream Cheese Stuffing drizzled with Teriyaki Fish Sauce Chef BB’s Cheesy Chili Cornbread $32.50 Crab-stuffed Mushrooms Homemade cornbread infused with Green Chili Peppers, Corn, and Cheddar Cheese Roast Beef Sliders (12) $39.50 Mini-Muffaletta Sliders (12) $38.00 New Orleans’ favorite Po’Boy Sandwich New Orleans-style Muffaletta Sliders made with thin-sliced Roast Beef and Chef BB’s with Smoked Ham, Provolone, Swiss, Salami Garlic Brown Gravy served on Slider Rolls and homemade Olive Tapenade Southern